Geographic Variation, Hybridization, and Taxonomy of New World Butorides Herons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Klamath Network Featured Creature November 2013 Green Heron (Butorides Virescens)

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Klamath Network Featured Creature November 2013 Green Heron (Butorides virescens) fish, insects, spiders, Atlantic coast into South crustaceans, snails, amphibians, Carolina. Green Herons are reptiles and rodents. widely dispersed and common, the largest threat to these birds Behavior: is habitat loss through the Green herons stalk prey by destruction and development of standing still or walking slowly wetlands. in shallow water with thick Interesting Fact: Pierre Howard vegetation. When prey The green heron is known to approaches the heron will dart use objects such as twigs, General Description: Found in and grasp or spear prey with feathers, or insects to lure small stalking sheltered edges of its sharp and heavy bill. Herons fish to the surface. This freshwater bodies, the green hunt at all times of day or night, behavior makes the green heron heron may first appear to be a in shallow brackish water, one of the few bird species that non-descript little bird. Seen in generally avoiding habitat uses tools! the light however, they have frequented by longer-legged deep green to blue-grey back herons. Where to Find in the Klamath and wings, a dark crested head, Network Parks: with a rich chestnut breast and Butorides virescens can be found in neck, and yellow to orange legs. Redwood National and State Juveniles are understated, with Parks, Whiskeytown National brown and cream streaks and Recreation Area, Lava Beds spots. The green heron is more National Monument, and is compact than other herons. probably present in Lassen They have shorter legs, broad Volcanic National Park. -

The Predominance of Wild-Animal Suffering Over Happiness: an Open

The Predominance of Wild-Animal Suffering over Happiness: An Open Problem Abstract I present evidence supporting the position that wild animals, taken as a whole, experience more suffering than happiness. This seems particularly true if, as is possible if not very likely, insects1 can suffer, since insects have lifespans of only a few weeks and are orders of magnitude more preponderate than other animals. I do not know what should be done about this problem, but I propose that further work on the subject might include • Continued study of whether insects are sentient, • Investigation of the effects (negative and positive) of various types of environ- mental destruction on wild-animal welfare, and • Research on ways to alleviate the pain endured by animals in the wild, especially that of insects and other small animals. Of course, even if wild-animal lives are generally worth living, efforts to reduce their suffering may still be worthwhile. I encourage readers to contact me with any insights into these issues: webmaster [\at"] utilitarian-essays.com 1 Introduction The fact that in nature one creature may cause pain to another, and even deal with it instinctively in the most cruel way, is a harsh mystery that weighs upon us as long as we live. One who has reached the point where he does not suffer ever again because of this has ceased to be a man. |Albert Schweitzer [31, Ch. 3] Many advocates of animal welfare assume that animals in the wild are, on the whole, happy. For instance, the site utilitarian.org includes a proposal to create a wildlife reserve, the main \Utility value" of which would come from \The value of life over death for the animals who will live there" [62]. -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

Ecuador's Biodiversity Hotspots

Ecuador’s Biodiversity Hotspots Destination: Andes, Amazon & Galapagos Islands, Ecuador Duration: 19 Days Dates: 29th June – 17th July 2018 Exploring various habitats throughout the wonderful & diverse country of Ecuador Spotting a huge male Andean bear & watching as it ripped into & fed on bromeliads Watching a Eastern olingo climbing the cecropia from the decking in Wildsumaco Seeing ~200 species of bird including 33 species of dazzling hummingbirds Watching a Western Galapagos racer hunting, catching & eating a Marine iguana Incredible animals in the Galapagos including nesting flightless cormorants 36 mammal species including Lowland paca, Andean bear & Galapagos fur seals Watching the incredible and tiny Pygmy marmoset in the Amazon near Sacha Lodge Having very close views of 8 different Andean condors including 3 on the ground Having Galapagos sea lions come up & interact with us on the boat and snorkelling Tour Leader / Guides Overview Martin Royle (Royle Safaris Tour Leader) Gustavo (Andean Naturalist Guide) Day 1: Quito / Puembo Francisco (Antisana Reserve Guide) Milton (Cayambe Coca National Park Guide) ‘Campion’ (Wildsumaco Guide) Day 2: Antisana Wilmar (Shanshu), Alex and Erica (Amazonia Guides) Gustavo (Galapagos Islands Guide) Days 3-4: Cayambe Coca Participants Mr. Joe Boyer Days 5-6: Wildsumaco Mrs. Rhoda Boyer-Perkins Day 7: Quito / Puembo Days 8-10: Amazon Day 11: Quito / Puembo Days 12-18: Galapagos Day 19: Quito / Puembo Royle Safaris – 6 Greenhythe Rd, Heald Green, Cheshire, SK8 3NS – 0845 226 8259 – [email protected] Day by Day Breakdown Overview Ecuador may be a small country on a map, but it is one of the richest countries in the world in terms of life and biodiversity. -

Moorestown Township Environmental Resource Inventory

APPENDIX C Vertebrate Animals Known or Probable in Moorestown Township Mammals Common Name Scientific Name Status Opossum Didelphis marsupialis Stable Eastern Mole Scalopus aquaticus Stable Big Brown Bat Eptesicus fuscus Stable Little Brown Bat Myotis lucifugus Stable Eastern Cottontail Sylvilagus floridanus Stable Eastern Chipmunk Tamias striatus Stable Gray Squirrel Sciurus carolinensis Stable White-footed Mouse Peromyscus leucopus Stable Meadow Vole Microtus pennsylvanicus Stable Muskrat Ondatra zibethicus Stable Pine Vole Microtus pinetorum Stable Red Fox Vulpes vulpes Stable Gray Fox Urocyon cinereoargenteus Stable Raccoon Procyon lotor Stable Striped Skunk Mephitis mephitis Stable River Otter Lutra canadensis Stable Beaver Castor candensis Increasing White-tailed Deer Odocoileus virginianus Decreasing Source: NJDEP, 2012 C-1 Birds Common Name Scientific Name NJ State Status Loons - Grebes Pied-Billed Grebe Podilymbus podiceps E Gannets - Pelicans - Cormorants Double Crested Cormorant Phalacrocorax auritus S Bitterns - Herons - Ibises American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus E Least Bittern Ixobrychus exilis SC Black Crowned Night Heron Nycticorax nycticorax T Green Heron Butorides virescens RP Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias SC Great Egret Ardea alba RP Geese - Swans - Ducks Canada Goose Branta canadensis INC Snow Goose Chen caerulescens INC American Wigeon Anas americana S Common Merganser Mergus merganser S Hooded Merganser Lophodytes cucullatus S Green-winged Teal Anas carolinensis RP Mallard Anas platyrhynchos INC Northern Pintail -

Conserving the Biodiversity of Massachusetts in a Changing World

BioMap2 CONSERVING THE BIODIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS IN A CHANGING WORLD MA Department of Fish & Game | Division of Fisheries & Wildlife | Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program n The Nature Conservancy COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS THE NATURE CONSERVANCY DEVAL L. PATRICK, Governor WAYNE KLOCKNER, State Director TIMOTHY P. MURRAY, Lieutenant Governor MASSACHUSETTS PROGRAM IAN A. BOWLES, Secretary BOARD OF TRUSTEES EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF ENERGY & JEFFREY PORTER, Chair (Wayland) ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS JOSE ALVAREZ (Mansfield) MARY B. GRIFFIN, Commissioner PAUL BAKSTRAN (Berlin) DEPARTMENT OF FISH & GAME MARCELLA BOELHOUWER (Weston) WAYNE F. MacCALLUM, Director SARAH BROUGHEL (Auburndale) DIVISION OF FISHERIES & WILDLIFE CHARLES CARLSON (Acton) FISHERIES & WILDLIFE BOARD ANNA COLTON (Winchester) GEORGE L. DAREY, Chair (Lenox) BOB DURAND (Marlborough) BONNIE BOOTH (Spencer) PAUL ELIAS (Cambridge) JOHN F. CREEDON, (North Easton) RICHARD FORMAN (Concord) JOSEPH S. LARSON, PhD (Pelham) DAVID FOSTER (Shutesbury) MICHAEL P. ROCHE (Orange) JOHN HAASE (Wayland) BRANDI VAN ROO, PhD (Douglas) MALCOLM HENDERSON (Beverly) FREDERIC WINTHROP (Ipswich) THOMAS JONES (Andover) DAVID LEATHERS (Winchester) NATURAL HERITAGE & ENDANGERED SPECIES ADVISORY COMMITTEE BRIAN MAZAR (Mendon) KATHLEEN S. ANDERSON, Chair (Middleborough) NINA McINTYRE (Winchester) MARILYN J. FLOR, (Rockport) ALICE RICHMOND (Boston) JOSEPH S. LARSON, PhD (Pelham) MARILYN SARLES (Wellesley Hills) MARK MELLO (South Dartmouth) GLENN MOTZKIN (Haydenville) THOMAS J. RAWINSKI (Oakham) JONATHAN -

Caribbean Ornithology

The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology RESEARCH ARTICLE Vol. 31:38–47. 2018 New sightings of melanistic Green Herons (Butorides virescens) in the Caribbean suggest overlooked polymorphism Jacob R. Drucker Ruth E. Bennett Lila K. Fried Mona L. Kazour Darin J. McNeil, Jr. Photo: Ruth E. Bennett The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology jco.birdscaribbean.org ISSN 1544-4953 RESEARCH ARTICLE Vol. 31:38–47. 2018 www.birdscaribbean.org New sightings of melanistic Green HeronsButorides ( virescens) in the Caribbean suggest overlooked polymorphism Jacob R. Drucker1, Ruth E. Bennett2,3, Lila K. Fried4, Mona L. Kazour5, and Darin J. McNeil, Jr.2,6 Abstract Intraspecific variation in animal coloration arises from the expression of heritable genes under different selection pressures and stochastic processes. Documenting patterns of intraspecific color variation is an important first step to under- standing the mechanisms that determine species appearance. Within the heron genus Butorides, plumage coloration varies across space, among distinct taxonomic groups, and within polymorphic populations. The melanistic Lava Heron (B. striata sundevalli) of the Galápagos has been the subject of considerable taxonomic confusion and debate, while an erythristic morph of Green Heron (B. virescens) has been largely overlooked in recent literature. Here we report a new sighting of three melanistic individuals of Green Heron from Útila, Bay Islands, Honduras, in February 2017. In light of our discovery, we conducted a review of aberrantly plumaged Green Herons and present evidence for the existence of two previously unrecognized color morphs, both primarily found in coastal mangroves of the western Caribbean region. We are the first to formally describe a melanistic morph of Green Heron and discuss the widespread and highly variable erythristic morph within the context of a color-polymor- phic Green Heron. -

Assam Extension I 17Th to 21St March 2015 (5 Days)

Trip Report Assam Extension I 17th to 21st March 2015 (5 days) Greater Adjutant by Glen Valentine Tour leaders: Glen Valentine & Wayne Jones Trip report compiled by Glen Valentine Trip Report - RBT Assam Extension I 2015 2 Top 5 Birds for the Assam Extension as voted by tour participants: 1. Pied Falconet 4. Ibisbill 2. Greater Adjutant 5. Wedge-tailed Green Pigeon 3. White-winged Duck Honourable mentions: Slender-billed Vulture, Swamp Francolin & Slender-billed Babbler Tour Summary: Our adventure through the north-east Indian subcontinent began in the bustling city of Guwahati, the capital of Assam province in north-east India. We kicked off our birding with a short but extremely productive visit to the sprawling dump at the edge of town. Along the way we stopped for eye-catching, introductory species such as Coppersmith Barbet, Purple Sunbird and Striated Grassbird that showed well in the scopes, before arriving at the dump where large frolicking flocks of the endangered and range-restricted Greater Adjutant greeted us, along with hordes of Black Kites and Eastern Cattle Egrets. Eastern Jungle Crows were also in attendance as were White Indian One-horned Rhinoceros and Citrine Wagtails, Pied and Jungle Mynas and Brown Shrike. A Yellow Bittern that eventually showed very well in a small pond adjacent to the dump was a delightful bonus, while a short stroll deeper into the refuse yielded the last remaining target species in the form of good numbers of Lesser Adjutant. After our intimate experience with the sought- after adjutant storks it was time to continue our journey to the grassy plains, wetlands, forests and woodlands of the fabulous Kaziranga National Park, our destination for the next two nights. -

Western Birds

WESTERN BIRDS Vol. 49, No. 4, 2018 Western Specialty: Golden-cheeked Woodpecker Second-cycle or third-cycle Herring Gull at Whiting, Indiana, on 25 January 2013. The inner three primaries on each wing of this bird appear fresher than the outer primaries. They may represent the second alternate plumage (see text). Photo by Desmond Sieburth of Los Angeles, California: Golden-cheeked Woodpecker (Melanerpes chrysogenys) San Blas, Nayarit, Mexico, 30 December 2016 Endemic to western mainland Mexico from Sinaloa south to Oaxaca, the Golden-cheeked Woodpecker comprises two well-differentiated subspecies. In the more northern Third-cycle (or possibly second-cycle) Herring Gull at New Buffalo, Michigan, on M. c. chrysogenys the hindcrown of both sexes is largely reddish with only a little 14 September 2014. Unlike the other birds illustrated on this issue’s back cover, in this yellow on the nape, whereas in the more southern M. c. flavinuchus the hindcrown is individual the pattern of the inner five primaries changes gradually from feather to uniformly yellow, contrasting sharply with the forehead (red in the male, grayish white feather, with no abrupt contrast. Otherwise this bird closely resembles the one on the in the female). The subspecies intergrade in Nayarit. Geographic variation in the outside back cover, although the prealternate molt of the other body and wing feathers Golden-cheeked Woodpecker has not been widely appreciated, perhaps because so many has not advanced as far. birders and ornithologists are familiar with the species from San Blas, in the center of Photos by Amar Ayyash the zone of intergradation. Volume 49, Number 4, 2018 The 42nd Annual Report of the California Bird Records Committee: 2016 Records Guy McCaskie, Stephen C. -

Selous & Ruaha

Selous & Ruaha - Undiscovered Tanzania Naturetrek Tour Report 28 September - 8 October 2017 Nile Crocodile Hippopotamus with Grey Heron & Cattle Egret White-crowned Lapwing Leopard Report & Images compiled by Zul Bhatia Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Selous & Ruaha - Undiscovered Tanzania Tour participants: Zul Bhatia (leader) with Metele Nduya (local guide & driver – Selous GR) Yustin Kayombo (local guide & driver – Ruaha NP), Together with six Naturetrek clients Summary The trip to southern Tanzania, visiting Selous Game Reserve and Ruaha National Park (staying four nights in each) lived up to all its expectations and more. We saw plenty of wildlife and often had it to ourselves with no other vehicles present – a nice feature of these less-visited places. It was particularly dry at Ruaha and the Great Ruaha River was reduced to a few pools. We saw some very exciting wildlife including hundreds of Crocodiles and Hippopotamus, many Greater Kudu and Elephants, 23 Lions, two Leopards, five Cheetahs and two African Civets. Mammal spotting was generally the order of most days with birds as a bonus. There were some very keen mammal observers in the group resulting in a list of 34 species of mammal. 170 species of bird were recorded including some very special ones of course, with highlights being Black and Woolly-necked Storks, Malagasy Pond Heron, Martial, African Fish and Verreaux’s Eagles, Grey-crowned Crane, White-crowned Lapwing, three species of roller, four of kingfisher and five of bee-eater. -

Birder's Guide to Birds of Landa Park

Birder’s to birds of GUIDE Landa Park Whether you’re a devoted birder or a casual observer, Landa Park is a great destination for bird watching. This scenic park provides nesting and feeding habitat for a large variety of bird species, both seasonally and year-round. The park’s 51 acres of green space include the Comal Springs, plants and groves of trees that support a great variety of birds, from yellow crowned night herons to red- shouldered hawks. Acknowledgements: This field checklist was created by Lynn Thompson of the Comal County Birders. Data compiled from eBird, Bill’s Earth and Comal County Birding records. Photo Credits: Dan Tharp Photos on front: Great Blue Heron, Crested Caracara, Inca Dove Photo above: Red-shouldered Hawk and Chick Photos on back: Yellow-crowned Night-Heron, Green Heron, Female Wood Duck “ We are fortunate to live in an area that is part of several migratory flyways, where there are abundant numbers of costal and shore birds, seasonal visitors from the south and west and many woodland species. Landa Park is a choice destination for any bird lover. ” - Dan Tharp Field Checklist to Birds of Landa Park Legend: X - recorded as seen, may not be common FAMILY/SPECIES Spring Summer Fall Winter Total # Blackbirds, Orioles and Grackles ____ Red-winged Blackbird X ____ Common Grackle X X X X ____ Great-tailed Grackle X X X X ____ Brown-headed Cowbird X X ____ Baltimore Oriole X Cardinals and Allies ____ Northern Cardinal X X X X ____ Indigo Bunting X Caracaras and Falcons ____ Crested Caracara X ____ American Kestrel -

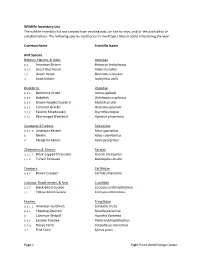

Master Wildlife Inventory List

Wildlife Inventory List The wildlife inventory list was created from existing data, on site surveys, and/or the availability of suitable habitat. The following species could occur in the Project Area at some time during the year: Common Name Scientific Name Bird Species Bitterns, Herons, & Allies Ardeidae D, E American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus A, E, F Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias E, F Green Heron Butorides virescens D Least bittern Ixobrychus exilis Blackbirds Icteridae B, E, F Baltimore Oriole Icterus galbula B, E, F Bobolink Dolichonyx oryzivorus B, E, F Brown-headed Cowbird Molothrus ater B, E, F Common Grackle Quiscalus quiscula B, E, F Eastern Meadowlark Sturnella magna B, E, F Red-winged Blackbird Agelaius phoeniceus Caracaras & Falcons Falconidae B, E, F, G American Kestrel Falco sparverius B Merlin Falco columbarius D Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus Chickadees & Titmice Paridae B, E, F, G Black-capped Chickadee Poecile atricapillus E, F, G Tufted Titmouse Baeolophus bicolor Creepers Certhiidae B, E, F Brown Creeper Certhia americana Cuckoos, Roadrunners, & Anis Cuculidae D, E, F Black-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus erythropthalmus E, F Yellow-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus americanus Finches Fringillidae B, E, F, G American Goldfinch Carduelis tristis B, E, F Chipping Sparrow Spizella passerina G Common Redpoll Acanthis flammea B, E, F Eastern Towhee Pipilo erythrophthalmus E, F, G House Finch Carpodacus mexicanus B, E Pine Siskin Spinus pinus Page 1 Eight Point Wind Energy Center E, F, G Purple Finch Carpodacus purpureus B, E Red Crossbill