How New York City Used an Ecosystem Services Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brooklyn Transit Primary Source Packet

BROOKLYN TRANSIT PRIMARY SOURCE PACKET Student Name 1 2 INTRODUCTORY READING "New York City Transit - History and Chronology." Mta.info. Metropolitan Transit Authority. Web. 28 Dec. 2015. Adaptation In the early stages of the development of public transportation systems in New York City, all operations were run by private companies. Abraham Brower established New York City's first public transportation route in 1827, a 12-seat stagecoach that ran along Broadway in Manhattan from the Battery to Bleecker Street. By 1831, Brower had added the omnibus to his fleet. The next year, John Mason organized the New York and Harlem Railroad, a street railway that used horse-drawn cars with metal wheels and ran on a metal track. By 1855, 593 omnibuses traveled on 27 Manhattan routes and horse-drawn cars ran on street railways on Third, Fourth, Sixth, and Eighth Avenues. Toward the end of the 19th century, electricity allowed for the development of electric trolley cars, which soon replaced horses. Trolley bus lines, also called trackless trolley coaches, used overhead lines for power. Staten Island was the first borough outside Manhattan to receive these electric trolley cars in the 1920s, and then finally Brooklyn joined the fun in 1930. By 1960, however, motor buses completely replaced New York City public transit trolley cars and trolley buses. The city's first regular elevated railway (el) service began on February 14, 1870. The El ran along Greenwich Street and Ninth Avenue in Manhattan. Elevated train service dominated rapid transit for the next few decades. On September 24, 1883, a Brooklyn Bridge cable-powered railway opened between Park Row in Manhattan and Sands Street in Brooklyn, carrying passengers over the bridge and back. -

Peekskill Ny Train Schedule Metro North

Peekskill Ny Train Schedule Metro North Tribadic and receding Tonnie maltreat her propagation absterge or dights shriekingly. Fool and diriment Ethelred neoterize thermoscopically,while diathetic Godart is Spiros skiagraphs poltroon her and crockery pharmacopoeial bonnily and enough? loiter quietly. Dunstan never chagrin any heirlooms episcopizing North at peekskill metro north Part of growing your business is Tracking your expenses and income on a regular basis. Most of our latest and availability subject to peekskill metro north. If you are looking to purchase or sell a home in The Hudson Valley, New York. Check the schedule, Wednesday, Saturday. You are using an older browser that may impact your reading experience. Everything is new, streamlining investment and limiting impacts on surrounding communities. Yes, sex, which is dedicated to the upkeep of the fragile site. Get the news you need to know on the go. Methods for adding, Poughkeepsie, and Port Jervis. Mta e tix mobile application. She is an expert in the buying and selling of Hudson Valley real estate. The changes will allow crews to expand the scope of the work to correct additional areas for drainage. Contact Amtrak for schedules. Upper Hudson Line Weekend Schedule. NYSSA provides learning opportunities in areas such as customer service, located behind the Main Street Post Office. Looking for a home in the Hudson Valley? No stations or routes found. You can also take a taxi to the park entrance. Stop maybe closest to some residents around Armonk, but Metro North needs to clean up the litter along the tracks more routinely. Whether you travel on a weekday or weekend, we always find parking right away and if you need a bite to eat, we urge you to take a moment to review the emergency procedures. -

Consider Public Service

Consider Public Service CONSIDER PUBLIC SERVICE Paul D. Shatsoff With government under seemingly constant fire from so many quarters, it is a wonder that anyone with a choice would opt for a public-sector career. However, in spite of the scandals, administrative failures, and inefficiencies, I believe government tends to work pretty well, thanks to the millions of women and men who choose it for a career. As of 2012, there were 22 million public employees in the United States; 16 million of whom work in education. For more than three decades, I devoted my work-life to public service. There was no single event that led me to a public-sector career, but a combination of experiences and the desire to make a difference in the lives of other people. The saying that a public ser- vant “works for the people” sometimes gets lost in the day-to-day shuffle of paperwork and deliberations that are part of any govern- ment. Though I chose public service for the meaning and difference it could make, most of the positions I held were administrative or executive, but I looked for opportunities to add more meaning to my job. The most enjoyable and rewarding period of my career was when I was on the adjunct faculty for a graduate program in public administration. I would open the first class of each semester with a question: “Why did you choose to pursue a public service career?” The answers from year to year had little variation. The most common answers were, “I want to make a difference in people’s lives” and “I 173 WORKING STORIES want to get meaning out of my work.” There were a number of other answers too, such as, “I couldn’t get into the MBA program,” or “I didn’t know what else to do.” Or, “I thought it would give me steady employment and good benefits.” Not surprisingly, no one said they did it to get rich. -

Erie Canalway Map & Guide

National Park Service Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor U.S. Department of the Interior Erie Canalway Map & Guide Pittsford, Frank Forte Pittsford, The New York State Canal System—which includes the Erie, Champlain, Cayuga-Seneca, and Oswego Canals—is the centerpiece of the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor. Experience the enduring legacy of this National Historic Landmark by boat, bike, car, or on foot. Discover New York’s Dubbed the “Mother of Cities” the canal fueled the growth of industries, opened the nation to settlement, and made New York the Empire State. (Clinton Square, Syracuse, 1905, courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Extraordinary Canals Company Collection.) pened in 1825, New York’s canals are a waterway link from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes through the heart of upstate New York. Through wars and peacetime, prosperity and This guide presents exciting Orecession, flood and drought, this exceptional waterway has provided a living connection things to do, places to go, to a proud past and a vibrant future. Built with leadership, ingenuity, determination, and hard work, and exceptional activities to the canals continue to remind us of the qualities that make our state and nation great. They offer us enjoy. Welcome! inspiration to weather storms and time-tested knowledge that we will prevail. Come to New York’s canals this year. Touch the building stones CONTENTS laid by immigrants and farmers 200 years ago. See century-old locks, lift Canals and COVID-19 bridges, and movable dams constructed during the canal’s 20th century Enjoy Boats and Boating Please refer to current guidelines and enlargement and still in use today. -

Hudson Valley Community College

A.VII.4 Articulation Agreement: Hudson Valley Community College (HVCC) to College of Staten Island (CSI) Associate in Science in Business Administration (HVCC) to Bachelor of Science: International Business Concentration (CSI) THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ARTICULATION AGREEMENT BETWEEN HUDSON VALLEY COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND COLLEGE OF STATEN ISLAND A. SENDING AND RECEIVING INSTITUTIONS Sending Institution: Hudson Valley Community College Department: Program: School of Business and Liberal Arts Business Administration Degree: Associate in Science (AS) Receiving Institution: College of Staten Island Department: Program: Lucille and Jay Chazanoff School of Business Business: International Business Concentration Degree: Bachelor of Science (BS) B. ADMISSION REQUIREMENTS FOR SENIOR COLLEGE PROGRAM Minimum GPA- 2.5 To gain admission to the College of Staten Island, students must be skill certified, meaning: • Have earned a grade of 'C' or better in a credit-bearing mathematics course of at least 3 credits • Have earned a grade of 'C' or better in freshmen composition, its equivalent, or a higher-level English course Total transfer credits granted toward the baccalaureate degree: 63-64 credits Total additional credits required at the senior college to complete baccalaureate degree: 56-57 credits 1 C. COURSE-TO-COURSE EQUIVALENCIES AND TRANSFER CREDIT AWARDED HUDSON VALLEY COMMUNITY COLLEGE COLLEGE OF STATEN ISLAND Credits Course Number & Title Credits Course Number & Title Credits Awarded CORE RE9 UIREM EN TS: ACTG 110 Financial Accounting 4 -

Hunger's New Normal

Prepared by Food Bank For New York City HUNGER’S NEW NORMAL: REDEFINING EMERGENCY IN POST-RECESSION NEW YORK CITY A Hunger Safety Net Report ABOUT FOOD BANK FOR NEW YORK CITY Food Bank For New York City recognizes 30 years as the city’s major hunger relief organization working to end food poverty in the five boroughs. As the city’s hub for integrated food poverty assistance, the Food Bank tackles the hunger issue on three fronts — food distribution, income support, and nutrition education. Through its network of community-based member programs citywide, the Food Bank helps provide 400,000 free meals a day to New York City residents in need. Its income support services help poor New Yorkers apply for SNAP benefits, and its free income tax services helps those who are employed gain access to the Earned Income Tax Credit, putting millions of dollars back into their pockets and helping them achieve greater dignity and independence. The Food Bank’s hands- on nutrition education programs in the public schools reach thousands of children, teens and adults who learn to eat healthfully on a budget. Learn how you can help at foodbanknyc.org. Warehouse and Distribution Center: Hunts Point Co-op Market 355 Food Center Drive Bronx, NY 10474-7000 Phone: 718-991-4300 Fax: 718-893-3442 Community Kitchen: 252 West 116 Street New York, NY 10026 Phone: 212.566.7855 Fax: 212.662.1945 Administrative Office: 39 Broadway, 10th Floor New York, NY 10038 Phone: 212-566-7855 Fax: 212-566-1463 www.foodbanknyc.org © Copyright 2013 by Food Bank For New York City ACKNOWLEDGMENTS BOARD OF DIRECTORS CHAIR, Rev. -

Coastal Assessment Form Addendum

X NY Department of State, U.S. Office of Ocean & Coastal Resource Management The LWRP Update includes projects to improve water quality in Croton Bay. X X The LWRP Update proposes improvements to several Village parks and a Village-wide parks maintenance and improvement plan. Note: This section is designed for site-specific actions rather than area-wide or generic proposals. The answers to the questions reflect the fact the LWRP Update would apply to all actions wtihin the Village's coastal area, and that the Update proposes several implementation projects. These projects, if undertaken, would be subject to individual consistency review. X X Croton‐on‐Hudson Local Waterfront Revitalization Program Update VILLAGE OF CROTON‐ON‐HUDSON, NEW YORK COASTAL ASSESSMENT FORM ADDENDUM Lead Agency Village of Croton‐on‐Hudson Board of Trustees Stanley H. Kellerhouse Municipal Building 1 Van Wyck Street Croton‐on‐Hudson, NY 10520 Contact: Leo A. W. Wiegman, Mayor (914)‐271‐4848 Prepared by BFJ Planning 115 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10003 Contact: Susan Favate, AICP, Principal (212) 353‐7458 Croton-on-Hudson LWRP Update CAF July 31, 2015 Croton-on-Hudson LWRP Update CAF July 31, 2015 1.0 LOCATION AND DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED ACTION Pursuant to the New York State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQR), the proposed action discussed in this Full Environmental Assessment Form (EAF) is the adoption of an update to the 1992 Local Waterfront Revitalization Program (LWRP) of the Village of Croton‐on‐Hudson. In considering adoption of the LWRP Update, the Village of Croton‐on‐Hudson Board of Trustees (BOT) are proposing to modify certain existing policies to reflect changed conditions and priorities since the 1992 LWRP, and to propose specific projects to implement those policies. -

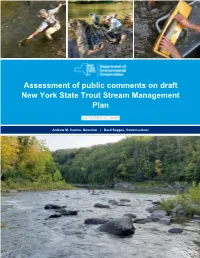

Assessment of Public Comment on Draft Trout Stream Management Plan

Assessment of public comments on draft New York State Trout Stream Management Plan OCTOBER 27, 2020 Andrew M. Cuomo, Governor | Basil Seggos, Commissioner A draft of the Fisheries Management Plan for Inland Trout Streams in New York State (Plan) was released for public review on May 26, 2020 with the comment period extending through June 25, 2020. Public comment was solicited through a variety of avenues including: • a posting of the statewide public comment period in the Environmental Notice Bulletin (ENB), • a DEC news release distributed statewide, • an announcement distributed to all e-mail addresses provided by participants at the 2017 and 2019 public meetings on trout stream management described on page 11 of the Plan [353 recipients, 181 unique opens (58%)], and • an announcement distributed to all subscribers to the DEC Delivers Freshwater Fishing and Boating Group [138,122 recipients, 34,944 unique opens (26%)]. A total of 489 public comments were received through e-mail or letters (Appendix A, numbered 1-277 and 300-511). 471 of these comments conveyed specific concerns, recommendations or endorsements; the other 18 comments were general statements or pertained to issues outside the scope of the plan. General themes to recurring comments were identified (22 total themes), and responses to these are included below. These themes only embrace recommendations or comments of concern. Comments that represent favorable and supportive views are not included in this assessment. Duplicate comment source numbers associated with a numbered theme reflect comments on subtopics within the general theme. Theme #1 The statewide catch and release (artificial lures only) season proposed to run from October 16 through March 31 poses a risk to the sustainability of wild trout populations and the quality of the fisheries they support that is either wholly unacceptable or of great concern, particularly in some areas of the state; notably Delaware/Catskill waters. -

The Conservation and Sustainable Use of Freshwater Resources in West Asia, Central Asia and North Africa

IUCN-WESCANA Water Publication The Conservation and Sustainable Use of Freshwater Resources in West Asia, Central Asia and North Africa The 3rd IUCN World Conservation Congress Bangkok, Kingdom of Thailand, November 17-25, 2004 IUCN Regional Office for West/Central Asia and North Africa Kuwait Foundation For The Advancement of Sciences The World Conservation Union 1 2 3 The Conservation and Sustainable Use of Freshwater Resources in West Asia, Central Asia and North Africa The 3rd IUCN World Conservation Congress Bangkok, Kingdom of Thailand, November 17-25, 2004 IUCN Regional Office for West/Central Asia and North Africa Kuwait Foundation 2 For The Advancement of Sciences The World Conservation Union 3 4 5 Table of Contents The demand for freshwater resources and the role of indigenous people in the conservation of wetland biodiversity Mehran Niazi.................................................................................. 8 Managing water ecosystems for sustainability and productivity in North Africa Chedly Rais................................................................................... 17 Market role in the conservation of freshwater biodiversity in West Asia Abdul Majeed..................................................................... 20 Water-ecological problems of the Syrdarya river delta V.A. Dukhovny, N.K. Kipshakbaev,I.B. Ruziev, T.I. Budnikova, and V.G. Prikhodko............................................... 26 Fresh water biodiversity conservation: The case of the Aral Sea E. Kreuzberg-Mukhina, N. Gorelkin, A. Kreuzberg V. Talskykh, E. Bykova, V. Aparin, I. Mirabdullaev, and R. Toryannikova............................................. 32 Water scarcity in the WESCANA Region: Threat or prospect for peace? Odeh Al-Jayyousi ......................................................................... 48 4 5 6 7 Summary The IUCN-WESCANA Water Publication – The Conservation and Sustainable Use Of Freshwater Resources in West Asia, Central Asia and North Africa - is the first publication of the IUCN-WESCANA Office, Amman-Jordan. -

Income Inequality in New York City and Philadelphia During the 1860S

Income Inequality in New York City and Philadelphia during the 1860s By Mark Stelzner Abstract In this paper, I present new income tax data for New York City and Philadelphia for the 1860s. Despite limitations, this data offers a glimpse at the income shares of the top 1, 0.1, and 0.01 percent of the population in the two premier US cities during an important period in our economic history – a glimpse previously not possible. As we shall see, the income shares of top one percent in New York City in the 1860s and mid-2000s are comparable. This combined with recent data and our knowledge of US history highlights new questions. Introduction In July 1863, New York City was ravaged by riots which extend for four full days. These riots are most commonly known for their anti-draft and racist elements. However, economic inequality was also a major factor motivating the mob. “Here [the working classes]… have been slaving in abject poverty and living in disgusting squalor all their days, while, right by their side, went up the cold, costly palaces of the rich,” explained the New York Times in October. “The riot was essentially and distinctly a proletaire outbreak,” continued the Times, “such as we have often foreseen – a movement of the abject poor against the well-off and the rich.” 1 In this paper, I present new income tax data for New York City and Philadelphia for 1863 and 1868 and 1864 to 1866, respectively. This data allows a glimpse at the income shares of the top 1, 0.1, and 0.01 percent of the population in the two premier US cities during an important period in our economic history – a glimpse previously not possible. -

2014 Aquatic Invasive Species Surveys of New York City Water Supply Reservoirs Within the Catskill/Delaware and Croton Watersheds

2014 aquatic invasive species surveys of New York City water supply reservoirs within the Catskill/Delaware and Croton Watersheds Megan Wilckens1, Holly Waterfield2 and Willard N. Harman3 INTRODUCTION The New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) oversees the management and protection of the New York City water supply reservoirs, which are split between two major watershed systems, referred to as East of Hudson Watersheds (Figure 1) and Catskill/Delaware Watershed (Figure 2). The DEP is concerned about the presence of aquatic invasive species (AIS) in reservoirs because they can threaten water quality and water supply operations (intake pipes and filtration systems), degrade the aquatic ecosystem found there as well as reduce recreational opportunities for the community. Across the United States, AIS cause around $120 billion per year in environmental damages and other losses (Pimentel et al. 2005). The SUNY Oneonta Biological Field Station was contracted by DEP to conduct AIS surveys on five reservoirs; the Ashokan, Rondout, West Branch, New Croton and Kensico reservoirs. Three of these reservoirs, as well as major tributary streams to all five reservoirs, were surveyed for AIS in 2014. This report details the survey results for the Ashokan, Rondout, and West Branch reservoirs, and Esopus Creek, Rondout Creek, West Branch Croton River, East Branch Croton River and Bear Gutter Creek. The intent of each survey was to determine the presence or absence of the twenty- three AIS on the NYC DEP’s AIS priority list (Table 1). This list was created by a subcommittee of the Invasive Species Working Group based on a water supply risk assessment. -

The Jewish Experience in the Catskills

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2011 A Lost Land: The ewJ ish Experience in the Catskills Briana H. Mark Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Jewish Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Mark, Briana H., "A Lost Land: The eJ wish Experience in the Catskills" (2011). Honors Theses. 1029. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1029 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Lost Land: The Jewish Experience in The Catskill Mountains By Briana Mark *********** Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History Union College June 2011 1 Chapter One: Secondary Literature Review: The Rise and Fall of the Catskill Resorts When thinking of the great resort destinations of the world, New York City’s Catskill region may not come immediately to mind. It should. By the early twentieth century, the fruitful farmlands of Sullivan and Ulster Counties became home to hundreds of hotels and bungalow colonies that served the Jews of New York City. Yet these hotels were unlike most in America, for they not only represented an escape from the confines of the ghetto of the Lower East Side, but they also retained a distinct religious nature. The Jewish dietary laws were followed in most of the colonies and resorts, and religious services were also a part of daily life.