Primitive Accumulation, the Social Common, and the Contractual Lockdown of Recording Artists at the Threshold of Digitalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Songs Songs That Mention Joni (Or One of Her Songs)

Inspired by Joni - the Songs Songs That Mention Joni (or one of her songs) Compiled by: Simon Montgomery, © 2003 Latest Update: May 15, 2021 Please send comments, corrections or additions to: [email protected] © Ed Thrasher, March 1968 Song Title Musician Album / CD Title 1968 Scorpio Lynn Miles Dancing Alone - Songs Of William Hawkins 1969 Spinning Wheel Blood, Sweat, and Tears Blood, Sweat, and Tears 1971 Billy The Mountain Frank Zappa / The Mothers Just Another Band From L.A. Going To California Led Zeppelin Led Zeppelin IV Going To California Led Zeppelin BBC Sessions 1972 Somebody Beautiful Just Undid Me Peter Allen Tenterfield Saddler Thoughts Have Turned Flo & Eddie The Phlorescent Leech & Eddie Going To California (Live) Led Zeppelin How The West Was Won 1973 Funny That Way Melissa Manchester Home To Myself You Put Me Thru Hell Original Cast The Best Of The National Lampoon Radio Hour (Joni Mitchell Parody) If We Only Had The Time Flo & Eddie Flo & Eddie 1974 Kama Sutra Time Flo & Eddie Illegal, Immoral & Fattening The Best Of My Love Eagles On The Border 1975 Tangled Up In Blue Bob Dylan Blood On The Tracks Uncle Sea-Bird Pete Atkin Live Libel Joni Eric Kloss Bodies' Warmth Passarela Nana Caymmi Ponta De Areia 1976 Superstar Paul Davis Southern Tracks & Fantasies If You Donít Like Hank Williams Kris Kristofferson Surreal Thing Makes Me Think of You Sandy Denny The Attic Tracks Vol. 4: Together Again Turntable Lady Curtis & Wargo 7" 45rpm Single 1978 So Blue Stan Rogers Turnaround Happy Birthday (to Joni Mitchell) Dr. John Period On Horizon 1979 (We Are) The Nowtones Blotto Hello! My Name Is Blotto. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Teena Marie Fires Motown-Scene Withdrawn Manchild

Page ,4 The Retriever, September 10, ,980, My Bodyguard explores the perils of Adoloescence The film is an oddity among the current by Brian ippard crop of Hollywood because it stops to explore human values rather than ignore them or exploit them. And while the film frames their friendship in conflict it does not My Bodyguard is being touted by the dwell excessively on that conflict. It is nice to critics as this year's Breaking Away. This see a film strike a workable balance in these companson bemg drawn not so much trom terms. similarities in plot. although both films examine the perils of adolescence, as from The performances"1>f Chris Makepeace as similarities in sensibilities. Both are honest, Clifford Peache and Adam Baldwin as sensitive, intelligent and genuinely funny Rickey Linderman are the focus and the films which examine the human character. highlight of this film. Chris Makepeacedoes Breaking Away wasthestor. offouryoung a fine job as the brash and intuitive Clifford men struggling to define their lives upon Peache. While Adam Baldwin as the graduation from high school. Theirs was a brooding Rickey Linderman turns in a struggle for identity. Iy Bodyguard. on the impressive debut performance. other hand, is a story about a friendship between two young men. A friendship which Matt Dillion plays Mooney, the chief we are alIowed to watch grow and blossom. bully with style and considerable flair. he is a nasty little brute and this performance should win him a spot in the halls of My Bodyguard is the story of 15 year old cinematic villianrv. -

Racial Gatekeeping in Country & Hip-Hop Music

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 12-14-2020 Racial Gatekeeping in Country & Hip-Hop Music Cervanté Pope Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social Psychology and Interaction Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Pope, Cervanté, "Racial Gatekeeping in Country & Hip-Hop Music" (2020). University Honors Theses. Paper 957. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.980 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Racial Gatekeeping in Country & Hip-Hop Music By Cervanté Pope Student ID #: 947767021 Portland State University Pope 2 Introduction In mass communication, gatekeeping refers to how information is edited, shaped and controlled in efforts to construct a “social reality” (Shoemaker, Eichholz, Kim, & Wrigley, 2001). Gatekeeping has expanded into other fields throughout the years, with its concepts growing more and more easily applicable in many other aspects of life. One way it presents itself is in regard to racial inclusion and equality, and despite the headway we’ve seemingly made as a society, we are still lightyears away from where we need to be. Because of this, the concept of cultural property has become even more paramount, as a means for keeping one’s cultural history and identity preserved. -

The Top 200 Greatest Funk Songs

The top 200 greatest funk songs 1. Get Up (I Feel Like Being a Sex Machine) Part I - James Brown 2. Papa's Got a Brand New Bag - James Brown & The Famous Flames 3. Thank You (Falletinme Be Mice Elf Agin) - Sly & The Family Stone 4. Tear the Roof Off the Sucker/Give Up the Funk - Parliament 5. Theme from "Shaft" - Isaac Hayes 6. Superfly - Curtis Mayfield 7. Superstition - Stevie Wonder 8. Cissy Strut - The Meters 9. One Nation Under a Groove - Funkadelic 10. Think (About It) - Lyn Collins (The Female Preacher) 11. Papa Was a Rollin' Stone - The Temptations 12. War - Edwin Starr 13. I'll Take You There - The Staple Singers 14. More Bounce to the Ounce Part I - Zapp & Roger 15. It's Your Thing - The Isley Brothers 16. Chameleon - Herbie Hancock 17. Mr. Big Stuff - Jean Knight 18. When Doves Cry - Prince 19. Tell Me Something Good - Rufus (with vocals by Chaka Khan) 20. Family Affair - Sly & The Family Stone 21. Cold Sweat - James Brown & The Famous Flames 22. Out of Sight - James Brown & The Famous Flames 23. Backstabbers - The O'Jays 24. Fire - The Ohio Players 25. Rock Creek Park - The Blackbyrds 26. Give It to Me Baby - Rick James 27. Brick House - The Commodores 28. Jungle Boogie - Kool & The Gang 29. Shining Star - Earth, Wind, & Fire 30. Got To Give It Up Part I - Marvin Gaye 31. Keep on Truckin' Part I - Eddie Kendricks 32. Dazz - Brick 33. Pick Up the Pieces - Average White Band 34. Hollywood Singing - Kool & The Gang 35. Do It ('Til You're Satisfied) - B.T. -

Live Exchange Party Band Song List

Live Exchange Party Band Song List FUNK Uptown Funk-Bruno Mars Let's groove-EWF September-EWF Before I let go-maze I'll be around- Spinners That's the way- KC in the sunshine band Brick House- commodores Jamaica Funk-Tom Browne Da Butt- EU Ain't nobody- Chaka Khan Tell Me something good- Chaka Khan Candy- cameo Boogie Shoes-KC and the sunshine band Ladies night- Kool and the Gang Boogie Oogie- A taste of Honey Play that funky music- wild Cherry Superstition-Stevie Wonder Sign sealed delivered- Stevie Wonder Best of my Love-The Emotions To be real-Cheryl Lynn Funky town- Lipps INC Funky good time- James Brown Get up-James Brown I feel good-James Brown Bird- Morris Day and the Time Get down on it- Kool and the gang Drop The bomb- The Gap Band Give it to me Baby- Rick James Word up-Cameo Jungle love The bird Teena Marie - Square Biz Gap Band - Early in the morning Midnight Star - No parking on the dance Floor MJ - Dancing Machine Morris Day - Jungle Love RAP Snap your fingers-Lil John About the money- T.I. All I do is win- Dj Alright- Kendrick Lamar Summertime- Dj Jazzy Jeff & the fresh Prince Whip and Nae Nae-Silentó Hotline Bling- Drake California- Ricco Barrino Better have my money-Rihanna Hey ya- Outkast R&B Love Changes- mothers finest Tyrone-Erykah Badu On&On-Erykah Badu Just Friends-Musiq The way-Jill Scott He loves me-Jill Scott Between the sheets-Isley Brothers Foot steps in the dark-Isley Brothers Sweet thing-Chaka Khan Stay with me- Sam Smith All of Me- John legend Do for love- Bobby Caldwell Just the two of us-Bill Withers Dock -

Record-World-1979-10

Dedicated to the Needs of the MusicRecord Industry OCTOBER 6, 1979 $2.25 f7Tage 'HO' NOINVO '3'N 0W13 'IS If76Z 05093d 3Ava Z9 1108-L 0 its of the SI -LES E H, WIND & RE, "IN THE S, "WHO LISTENS T' GLES, "THE LC (prod. bWhite) (writers: 010" (prod. by Solley) (w arrivalofthis Ion Foster -W (Saggifire, s:Cummings-Pendlebury) (Aus- provesthatsuperst Ninth/Irvi/Foster Free lian Tumbleweed, EMU) (3:2'). worth its weight in g EAGLES (3:32). A t single fro he 5 -man Australian bardenergy, seductive LI-TE LONG RLI Am," LP, should bec akes U.S. debut with th s sweetguitarwork third consecutive smas op - rockerfeaturingnervous every cut. "Heartach this formidable group. ad vocals and a driving beat.the title cut are c lumbia 1-11093. n nstant AOR add. Arista 0468. lum 5E-508 (8.98). CHEAP TRICK, "DREAM POLI CARTER, "D VI PEOPLE;' byWerman) (writer: E" SZ o O (Screen Gems-EMI/A al (3:14). The titlecut / P yen Visions, al new LP fulfillsthe /Unichappell, BMI) (3:26). sides feat(e past Cheap Trick effo r gives ading Simpson (Valerie powerhouse rock rhy thismic-te k': 'n for ticvocalsportrayin wro:e with .leap parancia. Epic 9-507 guitarist Joh .98) DR. HOOK, "BETTER LOVE INCEROS, "TAKE ME TO YOUR LO 1E, T T (prod. by Haffkine) LEADER" (prod. by Wisser.) Deborah Harry and pen -Keith -Slate) (H (writer:Kjeldsen)(Blackwood, succeeded wonderf BMI) (2:59). The Dr BMI) (3:30). The herky-jerky rock low -up to last year's really taken off wi beat,sparklingkeyboard adds new album is full o' hits and this look and irresistible vocal hook mak3 pop, catchy hooks withitslightda this British band's first release 3 lyrics that have m. -

The Forging of a White Gay Aesthetic at the Saint, 1980–84

The Forging of a White Gay Aesthetic at the Saint, 1980–84 Feature Article Tim Lawrence University of East London Abstract An influential private party for white gay men that opened in downtown New York in 1980 and closed in 1988, the Saint was a prolific employer of high-profile DJs, yet their work has gone largely unanalysed. This article describes and contextualises the aesthetic of these DJs, paying particular attention to the way they initially embraced music recorded by African American musicians, yet shifted to a notably “whiter” sound across 1982 and 1983, during which time new wave and Hi-NRG recordings were heard much more regularly at the spot. The piece argues that this shift took place as a result of a number of factors, including the introduction of a consumer ethos at the venue, the deepening influence of identity politics and the encroaching impact of AIDS, which decimated the venue’s membership. These developments led Saint DJs to place an ever-greater emphasis on the creation of a smooth and seamless aesthetic that enhanced the crowd’s embrace of a synchronized dancing style. DJs working in electronic dance music scenes would go on to adopt important elements of this approach. Keywords: The Saint, DJing, whiteness, neoliberalism, AIDS Tim Lawrence is the author of Love Saves the Day: A History of Dance Music Culture (1970–79) (Duke, 2003) and Hold On to Your Dreams: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973–92 (Duke, 2009). He is currently writing a book on New York club culture, 1980–84, again for Duke, and leads the Music Culture: Theory and Production programme at the University of East London. -

Singers News

K a lub BEVERLY r a Singers News RECORDS o Volume 6 Issue 1 June 2004 11612 S Western k Orland Bowl has a contest every Thursday Latest Pop Hits Monthly releases are here for July Chicago, IL 60643 e Night at 10PM with weekly qualifiers for the 2004. C&W has Martina McBride, Terri Clark, R. 773-779-0066 finals in August. $150 prizes each for best male Proctor, Clint Black, J. Bates, Emerson Drive, Paisley/ and female finals winner. Lots of consolation Krauss, C. Morgan and T.Wilkinson. Pop features a prizes too. Say Hi to KJ Mark out there. You’ll duet by Seether and Lee, Clay Aiken, Britney, I Lohan, definitely have fun! Simple Plan, Sugababes, Seal, Teeq, and Cherie. Nice The Showtime at the Apollo tour comes June Top 10 at Beverly Records Rock release with Melissa Etheridge, the Calling, 1. Yeah by Usher on Soundchoice 8864 and 3401 and Top Hits to Chicago for auditions on Sunday June 27 Andrews/Jules, Counting Crows, Five For Fighting, H0405 at 10AM at the Symphony Center 67 East J. Mayer and Dave Matthews. Urban best seller 2. When The Sun Goes Down-Kenny Chesney & Uncle Kracker Adams in Chicago. Call them at 312-294 3808. features Patti Labelle, Teena Marie, Juvenile, Cassidy, on SC 3402 and 8865 and THGC0405 Auditions for the first 300 people. This is the Carl Thomas, young Gunz, K. West, Dilated Peoples 3. This Love-Maroon 5 on SC 3400 and 8865 and THGP0404 4. Naughty Girl - Beyonce on THGC0407 and SC 3408 show that Ella Fitzgerald got her start in 1934 And Ghostface. -

SOUL Publications, Inc. Records, 1955-2002

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt167nd8xg No online items Finding Aid for the SOUL Publications, Inc. records, 1955-2002 Processed by Simone Fujita in the Center for Primary Research and Training (CFPRT), with assistance from Kelley Wolfe Bachli, 2010; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. The processing of this collection was generously supported by Arcadia funds. UCLA Library, Performing Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm © 2008 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the SOUL Publications, 342 1 Inc. records, 1955-2002 Descriptive Summary Title: SOUL Publications, Inc. records, Date (inclusive): 1955-2002 Collection number: 342 Creator: SOUL Publications, Inc., 1966-1982 Extent: 70 document boxes (35 linear feet)6 shoeboxes1 oversize box Abstract: SOUL Magazine was the principal publication of SOUL Publications, Inc., a Los Angeles-based enterprise founded by Regina and Ken Jones in 1966. Initially established to engender greater visibility for Black artists in the music industry, SOUL ultimately provided a space for critical engagement with Black artistic expression as well as social issues. The collection includes newspaper and magazine issues, research and clipping files on artists and public figures, audio cassettes of interviews and performances, photographs, and administrative files. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. -

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Music

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 5 Number 1 Article 9 1-1-1985 Music Linda Kimbell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Linda Kimbell, Music, 5 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 245 (1985). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol5/iss1/9 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. V. Music A. Copyright 1. Copyright Infringement: Temporal Remoteness Is No Defense ABKCO Music, Inc. v. HarrisongsMusic, Ltd. 1 is the fourth round of litigation involving claims of copyright infringement against George Harrison, formerly of the Beatles. The first round began in 1971, when Bright Tunes Music Corporation brought an action against Harrison claiming that his song, "My Sweet Lord" infringed upon its copyright in the song "He's So Fine" by Ronald Mack. The case went to trial in 1976.2 In order to prevail in a copyright infringement action, the plaintiff must prove the defendant copied the protected work.3 Since the plaintiff rarely has direct evidence of copying, the courts allow proof by circum- stantial evidence. Two methods are permissible: (1) evidence that the defendant's work is substantially similar to the plaintiff's; and (2) evi- dence of the defendant's access to the plaintiff's work.4 These two types of circumstantial evidence give rise to an inference of copying. -

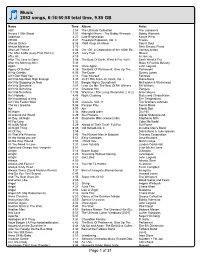

Tony's Itunes Library

Music 2053 songs, 6:16:50:58 total time, 9.85 GB Name Time Album Artist ABC 2:54 The Ultimate Collection The Jackson 5 Across 110th Street 3:51 Midnight Mover - The Bobby Womack ... Bobby Womack Addiction 4:27 Late Registration Kanye West AEIOU 8:41 Freestyle Explosion, Vol. 3 Freeze African Dance 6:08 1989 Keep On Movin' Soul II Soul African Mailman 3:10 Nina Simone Piano Afro Loft Theme 6:06 Om 100: A Celebration of the 100th Re... Various Artists The After 6 Mix (Juicy Fruit Part Ll) 3:25 Juicy Fruit Mtume After All 4:19 Al Jarreau After The Love Is Gone 3:58 The Best Of Earth, Wind & Fire Vol.II Earth Wind & Fire After the Morning After 5:33 Maze ft Frankie Beverly Again 5:02 Once Again John Legend Agony Of Defeet 4:28 The Best Of Parliament: Give Up The ... Parliament Ai No Corrida 6:26 The Dude Quincy Jones Ain't Gon' Beg You 4:14 Free Yourself Fantasia Ain't No Mountain High Enough 3:30 25 #1 Hits From 25 Years, Vol. I Diana Ross Ain't No Stopping Us Now 7:03 Boogie Nights Soundtrack McFadden & Whitehead Ain't No Sunshine 2:07 Lean On Me: The Best Of Bill Withers Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine 3:44 Greatest Hits Dangelo Ain't No Sunshine 11:04 Wattstax - The Living Word (disc 2 of 2) Isaac Hayes Ain't Nobody 4:48 Night Clubbing Rufus and Chaka Kahn Ain't too proud to beg 2:32 The Temptations Ain't We Funkin' Now 5:36 Classics, Vol.