Download Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Together We Can Do Great Things Gyda'n Gilydd, Gallwn Wneud

Together we can do great things Gyda’n gilydd, gallwn wneud pethau mawr Headteacher/Prifathro Mrs S Parry Headteachers Blog Number 136 Blog Prifathro Rhif 5th March 2021 Dear Parents, Guardians and Students/Annwyl Rieni,Gwarchodwyr a Myfyrwyr LHS - the return This week, we received the wonderful news that infection rates in Wales have reduced to a rate that Welsh Government consider it safe for us to formally plan for the staggered return of all students from 15th March. On Monday 8th March I will send our comprehensive plans to all stakeholders to allow everyone to get ready to return. We are reviewing all risk assessments and health and safety processes around the school. As part of this, we will be sending out guidance and resources for the optional use of lateral flow testing for staff and students. Rest assured that we will temper our enthusiasm to get back with our commitment to health and safety. There will be significant additional measures in place. We are preparing all details in preparation to update you on Monday. Patagonia bound on our 100 Heroes Charity and Fitness Event! In the meantime, please do follow the link below to view a very special video message that has been made by the staff of City Hospice to talk about the impact that our 100 Heroes campaign can have on the work that they do. We are really touched to hear from the amazing staff who work at City Hospice. We are making the journey of 12,000km to Patagonia because City Hospice has provided love and care for many members of our community and is close to our heart. -

NATIONAL ACADEMIES of SCIENCES and ENGINEERING NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL of the UNITED STATES of AMERICA

NATIONAL ACADEMIES OF SCIENCES AND ENGINEERING NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA UNITED STATES NATIONAL COMMITTEE International Union of Radio Science National Radio Science Meeting 4-8 January 2000 Sponsored by USNC/URSI University of Colorado Boulder, Colorado U.S.A. United States National Committee INTERNATIONAL UNION OF RADIO SCIENCE PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS National Radio Science Meeting 4-8 January 2000 Sponsored by USNC/URSI NOTE: Programs and Abstracts of the USNC/URSI Meetings are available from: USNC/URSI National Academy of Sciences 2101 Constitution Avenue, N.W. Washington, DC 20418 at $5 for 1983-1999 meetings. The full papers are not published in any collected format; requests for them should be addressed to the authors who may have them published on their own initiative. Please note that these meetings are national. They are not organized by the International Union, nor are the programs available from the International Secretariat. ii MEMBERSHIP United States National Committee INTERNATIONAL UNION OF RADIO SCIENCE Chair: Gary Brown* Secretary & Chair-Elect: Umran S. !nan* Immediate Past Chair: Susan K. Avery* Members Representing Societies, Groups, and Institutes: American Astronomical Society Thomas G. Phillips American Geophysical Union Donald T. Farley American Meteorological Society vacant IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society Linda P.B. Katehi IEEE Geosciences and Remote Sensing Society Roger Lang IEEE Microwave Theory and Techniques Society Arthur A. Oliner Members-at-Large: Amalia Barrios J. Richard Fisher Melinda Picket-May Ronald Pogorzelski W. Ross Stone Richard Ziolkowski Chairs of the USNC/URSI Commissions: Commission A Moto Kanda Commission B Piergiorgio L. E. Uslenghi Commission C Alfred 0. -

CALENDAR 2011 Sydney.Edu.Au/Calendar Calendar 2011 Calendar 2011

CALENDAR 2011 sydney.edu.au/calendar Calendar 2011 Calendar 2011 The Arms of the University Sidere mens eadem mutato Though the constellations change, the mind is universal The Arms Numbering of resolutions The following is an extract from the document granting Arms to the Renumbering of resolutions is for convenience only and does not University, dated May 1857: affect the interpretation of the resolutions, unless the context otherwise requires. Argent on a Cross Azure an open book proper, clasps Gold, between four Stars of eight points Or, on a chief Gules a Lion passant guardant Production also Or, together with this motto "Sidere mens eadem mutato" ... to Web and Print Production, Marketing and Communications be borne and used forever hereafter by the said University of Sydney Website: sydney.edu.au/web_print on their Common Seal, Shields, or otherwise according to the Law of Arms. The University of Sydney NSW 2006 Australia The motto, which was devised by FLS Merewether, Second Vice- Phone: +61 2 9351 2222 Provost of the University, conveys the feeling that in this hemisphere Website: sydney.edu.au all feelings and attitudes to scholarship are the same as those of our CRICOS Provider Code: 00026A predecessors in the northern hemisphere. Disclaimer ISSN: 0313-4466 This publication is copyright and remains the property of the University ISBN: 978-1-74210-173-6 of Sydney. This information is valid at the time of publication and the University reserves the right to alter information contained in the Calendar. Calendar 2010 ii Contents -

Edward George Bowen

AWA Newsletter #48 December 2009 A Member Reflections: of the SARL Things are really warming and whistles and can even using. “That sounds pretty up, the bands, the weather switch the kettle on for us. impressive,” the voice on the and even the shops, as all other end says. “This side We get with it, a fully syn- start to gear themselves using a homebrew QRP rig Antique thesised 1Kw linear which up for the “silly season”. running 1 watt into a in- Wireless Association will be programmed to only verted V at 6m”. Who do you I call it this because it just put out 400w maximum of Southern Africa think is getting the most seems to me this is the (Ha Ha) and buy a log peri- enjoyment out of his hobby ? time of year when every- odic beam that does all the one who was at least a frequencies. That’s what I love about little bit sane, tends to valve rigs and old Boat An- Inside this issue: We get on the air, switch in lose it all. chors. They give you as the graphic equaliser, CW Net 2 much enjoyment as the QRP We’ve reined ourselves in speech processor and DSP homebrew rig because you up until now. Not over- with automatic noise got it up and running after a SSB Activity 2 spent or maxed out the blanking and signal en- long arduous struggle of credit card. Kept the hancement like you have cleaning and refurbishing. spending of extra cash to a never seen, and call CQ. -

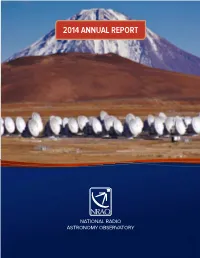

Annual Report 2014 C.Indd

2014 ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL RADIO ASTRONOMY OBSERVATORY 1 NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE NRAO SCIENCE 485 EMPLOYEES 51 MEDIA RELEASES 535 REFEREED SCIENCE PUBLICATIONS PROPOSAL AUTHORS FISCAL YEAR 2014 1425 – NRAO SEMESTER 2014B NRAO / ALMA OPERATIONS 1432 – NRAO SEMESTER 2015A $79.9 M 1500 – ALMA CYCLE 2, NA EXECUTIVE ALMA CONSTRUCTION $12.4 M EVLA CONSTRUCTION A SUITE OF FOUR $0.1 M WORLD-CLASS ASTRONOMICAL EXTERNAL GRANTS OBSERVATORIES $4.6 M NRAO FACTS & FIGURES $ 2 Contents DIRECTOR’S REPORT. .5 . NRAO IN BRIEF . 6 SCIENCE HIGHLIGHTS . 8 ALMA CONSTRUCTION. 24. OPERATIONS & DEVELOPMENT . 28 SCIENCE SUPPORT & RESEARCH . 58 TECHNOLOGY . 74 EDUCATION & PUBLIC OUTREACH. 82 . MANAGEMENT TEAM & ORGANIZATION. .86 . PERFORMANCE METRICS . 94 APPENDICES A. PUBLICATIONS . 100. B. EVENTS & MILESTONES . .126 . C. ADVISORY COMMITTEES . 128 D. FINANCIAL SUMMARY . .132 . E. MEDIA RELEASES . 134 F. ACRONYMS . 148 COVER: An international partnership between North America, Europe, East Asia, and the Republic of Chile, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) is the largest and highest priority project for the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, its parent organization, Associated Universities, Inc., and the National Science Foundation – Division of Astronomical Sciences. Operating at an elevation of more than 5000m on the Chajnantor plateau in northern Chile, ALMA represents an enormous leap forward in the research capabilities of ground-based astronomy. ALMA science operations were initiated in October 2011, and this unique telescope system is already opening new scientific frontiers across numerous fields of astrophysics. Credit: C. Padillo, NRAO/AUI/NSF. LEFT: The National Radio Astronomy Observatory Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array, located near Socorro, New Mexico, is a radio telescope of unprecedented sensitivity, frequency coverage, and imaging capability that was created by extensively modernizing the original Very Large Array that was dedicated in 1980. -

The Contribution of the Georges Heights Experimental Radar Antenna to Australian Radio Astronomy

Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 20(3), 313‒340 (2017). THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE GEORGES HEIGHTS EXPERIMENTAL RADAR ANTENNA TO AUSTRALIAN RADIO ASTRONOMY Wayne Orchiston and Harry Wendt National Astronomical Research Institute of Thailand, 260 Moo 4, T. Donkaew, A. Maerim, Chiang Mai 50180, Thailand. Emails: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract: During the late 1940s and throughout the1950s Australia was one of the world’s foremost astronomical nations owing primarily to the dynamic Radio Astronomy Group within the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Organisation’s Division of Radiophysics based in Sydney. The earliest celestial observations were made with former WWII radar antennas and simple Yagi aerials attached to recycled radar receivers, before more sophisticated purpose-built radio telescopes of various types were designed and developed. One of the recycled WWII antennas that was used extensively for pioneering radio astronomical research was an experimental radar antenna that initially was located at the Division’s short-lived Georges Heights Field Station but in 1948 was relocated to the new Potts Hill Field Station in suburban Sydney. In this paper we describe this unique antenna, and discuss the wide-ranging solar, galactic and extragalactic research programs that it was used for. Keywords: Australia, radio astronomy, experimental radar antenna, solar monitoring, H-line survey, 1200 MHz all-sky survey, Sagittarius A, ‘Chris’ Christiansen, Jim Hindman, Fred Lehany, Bernie Mills, Harry Minnett, Jack Piddington, Don Yabsley 1 INTRODUCTION November 1961 (Robertson, 1992) the nature of Australian radio astronomy changed forever (see In 2003 the IAU Working Group on Historic Radio Sullivan, 2017). -

Contribution of the Division of Radiophysics Potts Hill Field

This file is part of the following reference: Wendt, Harry (2008) The contribution of the Division of Radiophysics Potts Hill and Murraybank Field Stations to international radio astronomy. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/7995 Harry Wendt Contribution of the Division of Radiophysics Potts Hill & Murraybank Field Stations to International Radio Astronomy 13. REFERENCES Alexander, F. E. S., 1945. Report on the Investigation of the 'Norfolk Island Effect'. DSIR, Radio Development Laboratory, (R.D. 1/518). Alfvén, H. and Herlofson, N., 1950. Cosmic Radiation and Radio Stars. Physical Review, 68, 616. Allen, C. W., 1947. Solar Radio-Noise at 200 Mc/s and its Relation to Solar Observations. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 107, 386-396. Allen, C. W., 1955. The Quiet and Active Sun - Introductory Lecture. In Van De Hulst, H. C. (Ed.) International Astronomical Union Symposium No.4 - Radio Astronomy. Jodrell Bank Experimental Station near Manchester, Cambridge University Press. Allen, C. W. and Gum, C. S., 1950. Survey of Galactic Radio-Noise at 200 MHz. Australian Journal of Scientific Research, 3, 224-233. Anonymous, 1933. New Radio Waves Traced to Centre of the Milky Way. New York Times. New York, 5 May 1933. Anonymous, 1947. C.S.I.R. Radiophysics Division Structure Chart. National Archives of Australia, Sydney, 972916 - C3830 - B3. Anonymous, 2006. Heritage Assets - Potts Hill Reservoirs Site. Sydney, Sydney Water, http://www.heritage.nsw.gov.au/index.html, 16 July 2008. Baade, W. and Minkowski, R., 1954. Identification of the Radio Sources in Cassiopeia, Cygnus A, and Puppis A. -

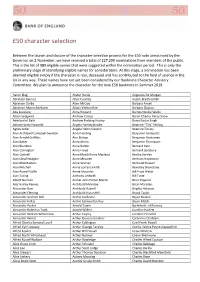

50 Character Selection

£50 character selection Between the launch and closure of the character selection process for the £50 note announced by the Governor on 2 November, we have received a total of 227,299 nominations from members of the public. This is the list of 989 eligible names that were suggested within the nomination period. This is only the preliminary stage of identifying eligible names for consideration: At this stage, a nomination has been deemed eligible simply if the character is real, deceased and has contributed to the field of science in the UK in any way. These names have not yet been considered by our Banknote Character Advisory Committee. We plan to announce the character for the new £50 banknote in Summer 2019. Aaron Klug Alister Hardy Augustus De Morgan Abraham Bennet Allen Coombs Austin Bradford Hill Abraham Darby Allen McClay Barbara Ansell Abraham Manie Adelstein Alliott Verdon Roe Barbara Clayton Ada Lovelace Alma Howard Barnes Neville Wallis Adam Sedgwick Andrew Crosse Baron Charles Percy Snow Aderlard of Bath Andrew Fielding Huxley Bawa Kartar Singh Adrian Hardy Haworth Angela Hartley Brodie Beatrice "Tilly" Shilling Agnes Arber Angela Helen Clayton Beatrice Tinsley Alan Archibald Campbell‐Swinton Anita Harding Benjamin Gompertz Alan Arnold Griffiths Ann Bishop Benjamin Huntsman Alan Baker Anna Atkins Benjamin Thompson Alan Blumlein Anna Bidder Bernard Katz Alan Carrington Anna Freud Bernard Spilsbury Alan Cottrell Anna MacGillivray Macleod Bertha Swirles Alan Lloyd Hodgkin Anne McLaren Bertram Hopkinson Alan MacMasters Anne Warner -

The Rise of Radio Astronomy in the Netherlands the People and the Politics Historical & Cultural Astronomy Historical & Cultural Astronomy

Historical & Cultural Astronomy Astrid Elbers The Rise of Radio Astronomy in the Netherlands The People and the Politics Historical & Cultural Astronomy Historical & Cultural Astronomy EDITORIAL BOARD Chairman W. BUTLER BURTON, National Radio Astronomy Observatory, Charlottes- ville, Virginia, USA ([email protected]); University of Leiden, The Netherlands, ([email protected]) JAMES EVANS, University of Puget Sound, USA MILLER GOSS, National Radio Astronomy Observatory, USA JAMES LEQUEUX, Observatoire de Paris, France SIMON MITTON, St. Edmund’s College Cambridge University, UK WAYNE ORCHISTON, National Astronomical Research Institute of Thailand, Thailand MARC ROTHENBERG, AAS Historical Astronomy Division Chair, USA VIRGINIA TRIMBLE, University of California Irvine, USA XIAOCHUN SUN, Institute of History of Natural Science, China GUDRUN WOLFSCHMIDT, Institute for History of Science and Technology, Germany More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15156 Astrid Elbers The Rise of Radio Astronomy in the Netherlands The People and the Politics 1 3 Astrid Elbers Institute for Language and Communication University of Antwerp Antwerp Belgium ISSN 2509-310X ISSN 2509-3118 (electronic) Historical & Cultural Astronomy ISBN 978-3-319-49078-6 ISBN 978-3-319-49079-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-49079-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016955789 © Springer International Publishing AG 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

Download Chapter 148KB

Memorial Tributes: Volume 8 EDWARD GEORGE BOWEN 20 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 8 EDWARD GEORGE BOWEN 21 Edward George Bowen 1911-1991 Written by R. Stevens Submitted by the NAE Home Secretary This is in Memory of Edward George ''Taffy'' Bowen. He was counsellor (scientific) to the Australian Embassy in Washington, D.C., chief of the Radiophysics Division of the Australian Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, and scientific officer of the British Air Ministry. He was a pioneer in the development of radar, radio astronomy, radio navigation, and experimental cloud physics. At critical times, in war and peace, he was instrumental in achieving cooperation between academic, industrial, and governmental organizations of the United Kingdom and the United States. Dr. Bowen died August 12, 1991. Edward George Bowen was born January 14, 1911, in Swansea, Wales. His parents were George and Ellen Ann Bowen. He attended University College, Swansea, earning a B.Sc. (first class physics honors) in 1930, and a M.Sc. in 1931. In 1934 he was awarded the Ph.D. by Kings College, London, for his research under radio physicist Professor Sir Edward Victor Appleton. In 1935 Dr. Bowen joined a small team of scientists led by Robert Watson- Watt to research and develop the new concept of radar. The work was under the British Air Ministry; it was a closely guarded secret. At Orfordness and Bawdsey, the team soon demonstrated detection of aircraft 100 miles distant. Bowen's role was development of the high-powered pulse Copyright National Academy of Sciences. -

The National Radio Astronomy Observatory and Its Impact on US Radio Astronomy Historical & Cultural Astronomy

Historical & Cultural Astronomy Series Editors: W. Orchiston · M. Rothenberg · C. Cunningham Kenneth I. Kellermann Ellen N. Bouton Sierra S. Brandt Open Skies The National Radio Astronomy Observatory and Its Impact on US Radio Astronomy Historical & Cultural Astronomy Series Editors: WAYNE ORCHISTON, Adjunct Professor, Astrophysics Group, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, QLD, Australia MARC ROTHENBERG, Smithsonian Institution (retired), Rockville, MD, USA CLIFFORD CUNNINGHAM, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, QLD, Australia Editorial Board: JAMES EVANS, University of Puget Sound, USA MILLER GOSS, National Radio Astronomy Observatory, USA DUANE HAMACHER, Monash University, Australia JAMES LEQUEUX, Observatoire de Paris, France SIMON MITTON, St. Edmund’s College Cambridge University, UK CLIVE RUGGLES, University of Leicester, UK VIRGINIA TRIMBLE, University of California Irvine, USA GUDRUN WOLFSCHMIDT, Institute for History of Science and Technology, Germany TRUDY BELL, Sky & Telescope, USA The Historical & Cultural Astronomy series includes high-level monographs and edited volumes covering a broad range of subjects in the history of astron- omy, including interdisciplinary contributions from historians, sociologists, horologists, archaeologists, and other humanities fields. The authors are distin- guished specialists in their fields of expertise. Each title is carefully supervised and aims to provide an in-depth understanding by offering detailed research. Rather than focusing on the scientific findings alone, these volumes explain the context of astronomical and space science progress from the pre-modern world to the future. The interdisciplinary Historical & Cultural Astronomy series offers a home for books addressing astronomical progress from a humanities perspective, encompassing the influence of religion, politics, social movements, and more on the growth of astronomical knowledge over the centuries. -

Astrophysics in 2000

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Astrophysics in 2000 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5272z5d3 Journal Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 113(787) ISSN 0004-6280 Authors Trimble, V Aschwanden, MJ Publication Date 2001-09-01 DOI 10.1086/322844 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 113:1025–1114, 2001 September ᭧ 2001. The Astronomical Society of the Pacific. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. Invited Review Astrophysics in 2000 Virginia Trimble Department of Astronomy, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742; and Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697 and Markus J. Aschwanden Lockheed Martin Advanced Technology Center, Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory, Department L9-41, Building 252, 3251 Hanover Street, Palo Alto, CA 94304; [email protected] Received 2001 April 13; accepted 2001 April 13 ABSTRACT. It was a year in which some topics selected themselves as important through the sheer numbers of papers published. These include the connection(s) between galaxies with active central engines and galaxies with starbursts, the transition from asymptotic giant branch stars to white dwarfs, gamma-ray bursters, solar data from three major satellite missions, and the cosmological parameters, including dark matter and very large scale structure. Several sections are oriented around processes—accretion, collimation, mergers, and disruptions—shared by a number of kinds of stars and galaxies. And, of course, there are the usual frivolities of errors, omissions, exceptions, and inventories.