Nontraumatic Knee Pain a Diagnostic & Treatment Guide Carlton J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recurrent Knee Effusions in Gymnast

12-648 LC WHITE Mid Atlantic Regional Chapter of the American College of Sports Medicine Annual Scientific Meeting, November 2nd - 3rd, 2018 Conference Proceedings International Journal of Exercise Science, Issue 9, Volume 7 Recurrent Knee Effusions in Gymnast Stephanie A. Carey, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, PA. email: [email protected] (Sponsor: Shawn Phillips, MD) History: A 20-year-old current college freshman sustained a right knee effusion following a hyperextension injury approximately 8 years ago while participating in gymnastics. Per report, workup at the time was negative, and she returned to gymnastics. She participated in gymnastics for 2 additional years and retired due to other interests. While continuing regular exercise, and participation in marching band, she reports recurrent, intermittent right knee effusions since that time. She reports that these would occur more often with repetitive activity. Over the past few months, her knee has been more significantly and persistently swollen. She exercises often, but reports no specific inciting incident. She reports pain with end range flexion. She denies any instability or locking. Previous physical therapy has improved her pain. Physical Examination: Examination revealed significant effusion of right knee. No obvious effusions in other joints. Range of motion was normal and pain free. Negative Lachman, anterior drawer, posterior drawer, varus and valgus stress testing , patellar grind, McMurray, Thessaly. Neurovascularly intact. Differential Diagnosis: 1. Meniscal tear, 2 Infection including possible Lyme Disease or Gonococcal Infection; 3. Rheumatoid Arthritis; 4. Gout; 5. Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis; 6. Hemophilia Test and Results: Aspiration: Bloody - >10000 RBCs, no crystals, normal WBC. -

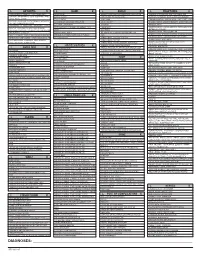

ICD-10 Diagnoses on Router

L ARTHRITIS R L HAND R L ANKLE R L FRACTURES R OSTEOARTHRITIS: PRIMARY, 2°, POST TRAUMA, POST _____ CONTUSION ACHILLES TEN DYSFUNCTION/TENDINITIS/RUPTURE FLXR TEN CLAVICLE: STERNAL END, SHAFT, ACROMIAL END CRYSTALLINE ARTHRITIS: GOUT: IDIOPATHIC, LEAD, CRUSH INJURY AMPUTATION TRAUMATIC LEVEL SCAPULA: ACROMION, BODY, CORACOID, GLENOID DRUG, RENAL, OTHER DUPUYTREN’S CONTUSION PROXIMAL HUMERUS: SURGICAL NECK 2 PART 3 PART 4 PART CRYSTALLINE ARTHRITIS: PSEUDOGOUT: HYDROXY LACERATION: DESCRIBE STRUCTURE CRUSH INJURY PROXIMAL HUMERUS: GREATER TUBEROSITY, LESSER TUBEROSITY DEP DIS, CHONDROCALCINOSIS LIGAMENT DISORDERS EFFUSION HUMERAL SHAFT INFLAMMATORY: RA: SEROPOSITIVE, SERONEGATIVE, JUVENILE OSTEOARTHRITIS PRIMARY/SECONDARY TYPE _____ LOOSE BODY HUMERUS DISTAL: SUPRACONDYLAR INTERCONDYLAR REACTIVE: SECONDARY TO: INFECTION ELSEWHERE, EXTENSION OR NONE INTESTINAL BYPASS, POST DYSENTERIC, POST IMMUNIZATION PAIN OCD TALUS HUMERUS DISTAL: TRANSCONDYLAR NEUROPATHIC CHARCOT SPRAIN HAND: JOINT? OSTEOARTHRITIS PRIMARY/SECONDARY TYPE _____ HUMERUS DISTAL: EPICONDYLE LATERAL OR MEDIAL AVULSION INFECT: PYOGENIC: STAPH, STREP, PNEUMO, OTHER BACT TENDON RUPTURES: EXTENSOR OR FLEXOR PAIN HUMERUS DISTAL: CONDYLE MEDIAL OR LATERAL INFECTIOUS: NONPYOGENIC: LYME, GONOCOCCAL, TB TENOSYNOVITIS SPRAIN, ANKLE, CALCANEOFIBULAR ELBOW: RADIUS: HEAD NECK OSTEONECROSIS: IDIOPATHIC, DRUG INDUCED, SPRAIN, ANKLE, DELTOID POST TRAUMATIC, OTHER CAUSE SPRAIN, ANKLE, TIB-FIB LIGAMENT (HIGH ANKLE) ELBOW: OLECRANON WITH OR WITHOUT INTRA ARTICULAR EXTENSION SUBLUXATION OF ANKLE, -

HYALURONIC ACID in KNEE OSTEOARTHRITIS Job Hermans

HYALURONIC ACID IN KNEE OSTEOARTHRITIS IN KNEE OSTEOARTHRITIS ACID HYALURONIC HYALURONIC ACID IN KNEE OSTEOARTHRITIS effectiveness and efficiency Job Hermans Job Hermans Hyaluronic Acid in Knee Osteoarthritis effectiveness and efficiency Job Hermans Part of the research described in this thesis was supported by a grant from ZonMW. Financial support for the publication of this thesis was kindly provided by: • Erasmus MC Department of Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine • Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging • Anna Fonds | NOREF • Apotheekgroep Breda • Össur Eindhoven • Bioventus The e-book version of this thesis is available at www.orthopeden.org/downloads/proefschriften ISBN 978-94-6416-168-7 Coverdesign and layout: Publiss.nl Printing: Ridderprint | www.ridderprint.nl © Job Hermans 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any other information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the holder of the copyright. Hyaluronic Acid in Knee Osteoarthritis effectiveness and efficiency Hyaluronzuur bij Knieartrose effectiviteit en efficiëntie Thesis to obtain the degree of Doctor from the Erasmus University Rotterdam by command of the rector magnificus Prof.dr. R.C.M.E. Engels and in accordance with the decision of the Doctorate Board. The public defense shall be held on November 24 2020 at 13:30hrs by Job Hermans Born in Boxmeer, the Netherlands Doctoral Committee Promotors Prof.dr. S.M.A. Bierma-Zeinstra Prof.dr. J.A.N. Verhaar Other members Prof.dr. S.K. Bulstra Prof.dr. J.M.W. Hazes Prof.dr. B.W. -

Adult and Adolescent Knee Pain Guideline Overview

Adult and Adolescent Knee Pain Guideline Overview This Guideline was adapted from and used with the permission of The UW Medical Foundation, UW Hospitals and Clinics, Meriter Hospital, University of Wisconsin Department of Family Medicine, Unity Health Insurance, Physicians Plus Insurance Corporation, and Group Health Cooperative, who created this guideline on May 18, 2007 as the result of a multidisciplinary work group comprised of health care practitioners from orthopedics, sports medicine, and rheumatology. This Guideline was reviewed and approved by Aspirus Network’s Medical Management Committee on May 7, 2013. The Knee Pain Work Group, a multidisciplinary work group comprised of health care practitioners from family practice, internal medicine, pediatric, and orthopedic surgery, participated in the development of this guideline. This guideline is intended to assist the patient-provider team to achieve the “Triple Aim”: quality, cost-efficient care with improved patient experiences / outcomes (i.e. do what’s best for the patient). Any distribution outside of Aspirus Network, Inc. is prohibited. Page 1 of 6 Adult and Adolescent Knee Pain Guideline Overview Guidelines are designed to assist clinicians by providing a framework for the evaluation and treatment of patients. This guideline outlines the preferred approach for most patients. It is not intended to replace a clinician’s judgment or to establish a protocol for all patients. It is understood that some patients will not fit the clinical condition contemplated by a guideline and that a guideline will rarely establish the only appropriate approach to a problem. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Patient Presents with Knee Pain ...................................................................... 3 2. History and Physical Exam ............................................................................. -

Pseudogout at the Knee Joint Will Frequently Occur After Hip Fracture

Harato and Yoshida Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research (2015) 10:4 DOI 10.1186/s13018-014-0145-9 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Pseudogout at the knee joint will frequently occur after hip fracture and lead to the knee pain in the early postoperative period Kengo Harato1,3*† and Hiroki Yoshida2† Abstract Background: Symptomatic knee joint effusion is frequently observed after hip fracture, which may lead to postoperative knee pain during rehabilitation after hip fracture surgery. However, unfortunately, very little has been reported on this phenomenon in the literature. The purpose of the current study was to investigate the relationship between symptomatic knee effusion and postoperative knee pain and to clarify the reason of the effusion accompanied by hip fracture. Methods: A total of 100 patients over 65 years of age with an acute hip fracture after fall were prospectively followed up. Knee effusion was assessed on admission and at the operating room before the surgery. If knee effusion was observed at thetimeofthesurgery,synovialfluidwascollectedintosyringes to investigate the cause of the effusion using a compensated polarized light microscope. Furthermore, for each patient, we evaluated age, sex, radiographic knee osteoarthritis (OA), type of the fracture, laterality, severity of the fracture, and postoperative knee pain during rehabilitation. These factors were compared between patients with and without knee effusion at the time of the surgery. As a statistical analysis, we used Mann–Whitney U-test for patients’ age and categorical variables were analyzed by chi-square test or Fisher’sexacttest. Results: A total of 30 patients presented symptomatic knee effusion at the time of the surgery. -

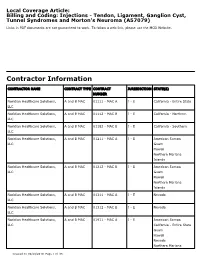

Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079)

Local Coverage Article: Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01111 - MAC A J - E California - Entire State LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01112 - MAC B J - E California - Northern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01182 - MAC B J - E California - Southern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01211 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01212 - MAC B J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01311 - MAC A J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01312 - MAC B J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01911 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC California - Entire State Guam Hawaii Nevada Northern Mariana Created on 09/28/2019. Page 1 of 33 CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Islands Article Information General Information Original Effective Date 10/01/2019 Article ID Revision Effective Date A57079 N/A Article Title Revision Ending Date Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, N/A Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma Retirement Date N/A Article Type Billing and Coding AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Statement CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are copyright 2018 American Medical Association. -

Knee Pain in Children: Part I: Evaluation

Knee Pain in Children: Part I: Evaluation Michael Wolf, MD* *Pediatrics and Orthopedic Surgery, St Christopher’s Hospital for Children, Philadelphia, PA. Practice Gap Clinicians who evaluate knee pain must understand how the history and physical examination findings direct the diagnostic process and subsequent management. Objectives After reading this article, the reader should be able to: 1. Obtain an appropriate history and perform a thorough physical examination of a patient presenting with knee pain. 2. Employ an algorithm based on history and physical findings to direct further evaluation and management. HISTORY Obtaining a thorough patient history is crucial in identifying the cause of knee pain in a child (Table). For example, a history of significant swelling without trauma suggests bacterial infection, inflammatory conditions, or less likely, intra- articular derangement. A history of swelling after trauma is concerning for potential intra-articular derangement. A report of warmth or erythema merits consideration of bacterial in- fection or inflammatory conditions, and mechanical symptoms (eg, lock- ing, catching, instability) should prompt consideration of intra-articular derangement. Nighttime pain and systemic symptoms (eg, fever, sweats, night sweats, anorexia, malaise, fatigue, weight loss) are associated with bacterial infections, inflammatory conditions, benign and malignant musculoskeletal tumors, and other systemic malignancies. A history of rash or known systemic inflammatory conditions, such as systemic lupus erythematosus or inflammatory bowel disease, should raise suspicion for inflammatory arthritis. Ascertaining the location of the pain also can aid in determining the cause of knee pain. Anterior pain suggests patellofemoral syndrome or instability, quad- riceps or patellar tendinopathy, prepatellar bursitis, or apophysitis (patellar or tibial tubercle). -

ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Acute Trauma to the Knee

Revised 2019 American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Acute Trauma to the Knee Variant 1: Adult or child 5 years of age or older. Fall or acute twisting trauma to the knee. No focal tenderness, no effusion, able to walk. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level Radiography knee May Be Appropriate ☢ Bone scan with SPECT or SPECT/CT knee Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT knee with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ CT knee without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ CT knee without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ MR arthrography knee Usually Not Appropriate O MRA knee without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRA knee without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRI knee without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRI knee without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O US knee Usually Not Appropriate O Variant 2: Adult or child 5 years of age or older. Fall or acute twisting trauma to the knee. One or more of the following: focal tenderness, effusion, inability to bear weight. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level Radiography knee Usually Appropriate ☢ Bone scan with SPECT or SPECT/CT knee Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT knee with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ CT knee without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ CT knee without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢ MR arthrography knee Usually Not Appropriate O MRA knee without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRA knee without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRI knee without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRI knee without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O US knee Usually Not Appropriate O ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 1 Acute Trauma to the Knee Variant 3: Adult or skeletally mature child. -

The Atraumatic Knee Effusion: Broadening the Differential Abcs of Musculoskeletal Care

12/12/2015 I have no disclosures. The Atraumatic Knee Effusion: Broadening the Differential ABCs of Musculoskeletal Care Carlin Senter, MD Primary Care Sports Medicine Departments of Medicine and Orthopaedics December 12, 2015 Objectives Case #1 At the end of this lecture you will know… 1. The differential diagnosis for a patient with atraumatic A 25 y/o woman presents with 2 weeks of increasingly painful monoarticular arthritis. atraumatic swelling of her left knee. 2. The keys to working this patient up No locking 1. Knee aspiration and interpretation No instability No fever or night sweats 2. Labs No recent GI or GU illness. Sexually active with one partner x 1 month. Exam: Difficulty bearing weight on the L leg, large L knee effusion, diffuse tenderness of the L knee, limited passive range of motion L knee due to pain, knee feels warm to touch. No skin erythema. 1 12/12/2015 What would you do next? Differential monoarticular arthritis Noninflammatory Septic • Osteoarthritis • Bacteria (remember gonorrhea, A. 2 week trial of NSAIDs + hydrocodone/APAP for breakthru pain Lyme disease) • Neuropathic arthropathy B. 2 week trial of NSAIDs + physical therapy • Mycobacteria Inflammatory C. Knee x-rays 56% • Fungus • Crystal arthropathy D. Knee aspiration Hemorrhagic ‒ Gout (Monosodium urate crystals) E. Blood work • Hemophilia ‒ CPPD (Calicium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals, aka pseudogout) • Supratherapeutic INR • Spondyloarthritis (involves low • Trauma 15% 15% back, but can be peripheral only, also can affect entheses) • Tumor 6% 8% ‒ Reactive arthritis (used to be called Reiter’s syndrome) ‒ Psoriatic arthritis . i o n . - r a y s ‒ IBD-associated s + . -

Surgical Guideline for Work-Related Knee Injuries 2016

Surgical Guideline for Work-related Knee Injuries 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Review Criteria for Knee Surgery .................................................................................... 2 II. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 9 A. Background and Prevalence ................................................................................................ 9 B. Establishing Work-relatedness .......................................................................................... 10 III. Assessment .................................................................................................................. 11 A. History and Clinical Examination ....................................................................................... 11 B. “Overuse Syndrome” and Contralateral Effects ................................................................ 11 C. Diagnostic Imaging ............................................................................................................. 12 IV. Non-Operative Care ...................................................................................................... 12 V. Surgical Procedures ...................................................................................................... 13 A. Marrow Stimulation Procedures ....................................................................................... 13 B. Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation ............................................................................ -

Patellofemoral SMCA 2014 Handout

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome / How can a Sesamoid Bone Anterior Knee Pain / Runners’ Knee cause So Many Problems? _ n Most common cause of Patellofemoral Pain and knee pain Patella Instability n Most common symptom presenting to SM n Diagnostic challenge n Treatment controversies n Lack of evidence to support Sarah Kerslake BPHTY Ax and Rx PFPS Patellofemoral Anatomy n Multifactorial Etiology n Considering the PF joint is one of the most n Non-operative treatment is successful highly loaded joints in the human body, the prevalence of AKP is not surprising. n Strong evidence supports treatment with multimodal therapy n Anatomy: n Sesamoid bone in extensor apparatus n Routine clinical Ax of muscle strength in athletes may not detect deficits n Acts as pulley/cam in extensor mechanism n Protects the tibiofemoral joint n More challenging functional tests required n Anchored by Active and Passive elements PFPS Anatomy PFPS Anatomy n Active (Dynamic) restraints n Passive (Static) restraints n Quadriceps muscle n Bony anatomy (Facets <=> Trochlea) n Vastus Lateralis Obliquus/Longus n Quadriceps Fascia + Patellar Tendon n Rectus Femoris + Vastus Intermedius n Lateral Peripatellar Retinaculum n Vastus Medialis Obliquus/Longus n Medial Peripatellar Retinaculum, particularly n Patella Tendon the medial patellofemoral ligament n Iliotibial band n Balance between structures is v. important 1 PFPS Symptoms PFPS Pathology n Symptoms include pain, swelling, n Patellar Tracking weakness, instability, mechanical n Patellar Tendinopathy symptoms & functional -

Plica: Pathologic Or Not? J

Plica: Pathologic or Not? J. Whit Ewing, MD Abstract A fold that occurs within a joint is referred to as a plica synovialis. Three such pli- in which the only finding to explain cae are seen with regularity within the human knee joint. These folds are normal the symptoms is the presence of a structures that represent remnants of mesenchymal tissue and/or septa formed thickened, hypertrophic plica. during embryonic development of the knee joint, and can be seen during arthro- Chronic anteromedial knee pain and scopic inspection of the knee joint. Controversy exists within the orthopaedic com- a sense of tightness in the subpatellar munity as to whether a plica can develop pathologic changes sufficient to cause region on squatting are the common disabling knee symptoms. The author defines the clinical syndrome, describes the complaints expressed by patients arthroscopic appearance of pathologic plica, and outlines nonsurgical and surgi- found to have a pathologic plica. The cal methods of management of this uncommon condition. ligamentum mucosum is not a J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1993;1:117-121 source of these types of symptoms. Additional symptoms are snapping sensations, buckling, knee pain on A plica synovialis is a membranous commonly referred to as a medial shelf sitting, and pain with repetitive fold or ridge found in the synovial or medial plica. This shelflike fold of activity.4 Recurrent effusions and lining of a joint. Three such folds are synovial membrane extends from the locking of the knee joint are not typi- found with regularity in the human infrapatellar fat pad to the medial wall cal in patients with this syndrome.