Rock and the Facts of Life (1970)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qveen Herby Download Free Ep 2 Qveen Herby

qveen herby download free ep 2 Qveen Herby. Amy Renee Heidemann Noonan (born April 29, 1986), known by her stage name Qveen Herby , [1] is an American rapper, singer, songwriter and entrepreneur. Born and raised in Seward, Nebraska, she first gained fame as part of the music duo Karmin, with whom she released two studio albums. Following the duo's hiatus in 2017, she began the solo project Qveen Herby, which incorporated R&B and hip hop influences. [2] She released her first solo extended play, EP 1 on June 2, 2017, preceded by the single " Busta Rhymes ". She released her debut album, A Woman on May 21, 2021. Career. 2010–2016: Music with Karmin. Heidemann began her musical career as a member of pop duo Karmin, with now-husband Nick Noonan, releasing cover songs on YouTube. The group signed with Epic Records and released their debut EP, Hello , on May 7, 2012, to poor reviews from critics; despite this, the EP was a commercial success supplemented by two hit singles: "Brokenhearted" peaked at number 16 on US Billboard Hot 100 charts, and peaked within the top ten of the charts in Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, while " Hello " peaked at number one on the Billboard Hot Dance Club Songs charts in the United States. [3] The duo followed Hello up by their debut full-length studio album, Pulses (2014), which saw less commercial success, and was supplemented by the single " Acapella ." Following the conclusion of promotion for Pulses , Karmin left Epic Records and began releasing music independently. -

FY14 Tappin' Study Guide

Student Matinee Series Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life Study Guide Created by Miller Grove High School Drama Class of Joyce Scott As part of the Alliance Theatre Institute for Educators and Teaching Artists’ Dramaturgy by Students Under the guidance of Teaching Artist Barry Stewart Mann Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life was produced at the Arena Theatre in Washington, DC, from Nov. 15 to Dec. 29, 2013 The Alliance Theatre Production runs from April 2 to May 4, 2014 The production will travel to Beverly Hills, California from May 9-24, 2014, and to the Cleveland Playhouse from May 30 to June 29, 2014. Reviews Keith Loria, on theatermania.com, called the show “a tender glimpse into the Hineses’ rise to fame and a touching tribute to a brother.” Benjamin Tomchik wrote in Broadway World, that the show “seems determined not only to love the audience, but to entertain them, and it succeeds at doing just that! While Tappin' Thru Life does have some flaws, it's hard to find anyone who isn't won over by Hines showmanship, humor, timing and above all else, talent.” In The Washington Post, Nelson Pressley wrote, “’Tappin’ is basically a breezy, personable concert. The show doesn’t flinch from hard-core nostalgia; the heart-on-his-sleeve Hines is too sentimental for that. It’s frankly schmaltzy, and it’s barely written — it zips through selected moments of Hines’s life, creating a mood more than telling a story. it’s a pleasure to be in the company of a shameless, ebullient vaudeville heart.” Maurice Hines Is . -

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

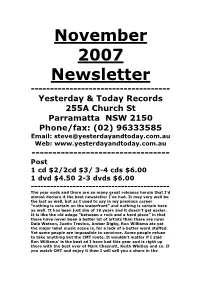

Newsletter November 2007

November 2007 Newsletter ------------------------------------ Yesterday & Today Records 255A Church St Parramatta NSW 2150 Phone/fax: (02) 96333585 Email: [email protected] Web: www.yesterdayandtoday.com.au --------------------------------- Post 1 cd $2/2cd $3/ 3-4 cds $6.00 1 dvd $4.50 2-3 dvds $6.00 ------------------------------------------- The year ends and there are so many great releases herein that I’d almost declare it the best newsletter I’ve had. It may very well be the last as well, but as I used to say in my previous career “nothing is certain on the waterfront” and nothing is certain here as well. It has been just shy of 19 years and it doesn’t get easier. It is like the old adage “between a rock and a hard place” in that there have never been a better lot of artists than there are now: Dale Watson, Justin Trevino, Amber Digby, Ron Williams etc yet the major label music scene is, for a lack of a better word stuffed. Yet some people are impossible to convince. Some people refuse to take anything but the CMT route. It wouldn’t matter if I said Ron Williams’ is the best cd I have had this year and is right up there with the best ever of Mark Chesnutt, Keith Whitley and co. If you watch CMT and enjoy it then I will sell you a share in the Sydney Harbour Bridge. If you watch it and question its merit we have the answers for you. Please read on. ----------------------------------- Ron Williams – “Texas Style” $32 If anything beats this as album of the year I will be very surprised. -

RAY STEVENS' Cabaray NASHVILLEPUBLIC TV 201 NEW

1. REVISION #3 3/20/2017 RAY STEVENS’ CabaRay NASHVILLEPUBLIC TV SYNDICATED EPISODES 201 - 252 PBS SHOW # GUEST(S) PERFORMANCES FEED DATE 201 Harold Bradley “Sgt. Preston of the Mounties” . NEW SHOW 7.07.2017 “Jeremiah Peabody’s Poly-Unsaturated, w.Mandy Barnett Quick Dissolving, Fast-Actin’, Pleasant Tastin’, Green and Purple Pills” .”Harry, The Hairy Ape” (RAY) “Crazy” & “I’m Confessin’” (MANDY) * 202 “Ned Nostril” (Ray) 7.14.2017 “Only You” (Ray) “Two Dozen Roses” (Shenandoah) “Sleepwalk” (A-Team) “I Want To Be Loved Like That” (Shenandoah) “Church On The Cumberland Road” (Shenandoah) * 203 Michael W. Smith “Dry Bones” (RAY) 7.21.2017 (GOSPEL THEME) “Would Jesus Wear A Rolex” (RAY) “This Ole House” (Ray) “I’ll Fly Away” (Duet w.Smitty) “Shine On Me” (SMITTY) 204 BJ Thomas ‘Hound Dog” (RAY) 7.28.2017 “Mr. Businessman” (duet w.BJ) “I Saw Elvis In A UFO” (RAY) “Rain Drops Keep Fallin’ On My Head” (chorus & verse BJ) “Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song” (BJ) * 205 Rhonda Vincent “King of the Road” (RAY) 8.04.2017 “Chug-A-Lug” (RAY) “Just A Closer Walk With Thee” (Duet w.Rhonda) “Jolene” * 206 Restless Heart “That Ole Black Magic” (RAY) 8.11.2017 Larry Steward “Spiders And Snakes” (RAY) John Dittrich “Everything Is Beautiful” (duet Paul Gregg With Restless Heart) David Innis “Bluest Eyes In Texas” (RESTLESS) Greg Jennings * 207 John Michael “Get Your Tongue Out 8.18.2017 Montgomery Of My Mouth, I’m Kissing You Goodbye” & “Retired” (RAY) “Letters From Home” & “Sold” (JOHN MICHAEL) 208 Ballie and the Boys “Little Egypt” & “Poison Ivy” (RAY) 8.25.2017 Kathie Bonagoura “(Wish I Had) A Heart of Stone” & Michael Bonagoura “House My Daddy Built” (BAILLIE) Molly Cherryholmes 2. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1950S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1950s Page 86 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1950 A Dream Is a Wish Choo’n Gum I Said my Pajamas Your Heart Makes / Teresa Brewer (and Put On My Pray’rs) Vals fra “Zampa” Tony Martin & Fran Warren Count Every Star Victor Silvester Ray Anthony I Wanna Be Loved Ain’t It Grand to Be Billy Eckstine Daddy’s Little Girl Bloomin’ Well Dead The Mills Brothers I’ll Never Be Free Lesley Sarony Kay Starr & Tennessee Daisy Bell Ernie Ford All My Love Katie Lawrence Percy Faith I’m Henery the Eighth, I Am Dear Hearts & Gentle People Any Old Iron Harry Champion Dinah Shore Harry Champion I’m Movin’ On Dearie Hank Snow Autumn Leaves Guy Lombardo (Les Feuilles Mortes) I’m Thinking Tonight Yves Montand Doing the Lambeth Walk of My Blue Eyes / Noel Gay Baldhead Chattanoogie John Byrd & His Don’t Dilly Dally on Shoe-Shine Boy Blues Jumpers the Way (My Old Man) Joe Loss (Professor Longhair) Marie Lloyd If I Knew You Were Comin’ Beloved, Be Faithful Down at the Old I’d Have Baked a Cake Russ Morgan Bull and Bush Eileen Barton Florrie Ford Beside the Seaside, If You were the Only Beside the Sea Enjoy Yourself (It’s Girl in the World Mark Sheridan Later Than You Think) George Robey Guy Lombardo Bewitched (bothered If You’ve Got the Money & bewildered) Foggy Mountain Breakdown (I’ve Got the Time) Doris Day Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs Lefty Frizzell Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo Frosty the Snowman It Isn’t Fair Jo Stafford & Gene Autry Sammy Kaye Gordon MacRae Goodnight, Irene It’s a Long Way Boiled Beef and Carrots Frank Sinatra to Tipperary -

Strange Brew√ Fresh Insights on Rock Music | Edition 03 of September 30 2006

M i c h a e l W a d d a c o r ‘ s πStrange Brew Fresh insights on rock music | Edition 03 of September 30 2006 L o n g m a y y o u r u n ! A tribute to Neil Young: still burnin‘ at 60 œ part two Forty years ago, in 1966, Neil Young made his Living with War (2006) recording debut as a 20-year-old member of the seminal, West Coast folk-rock band, Buffalo Springfield, with the release of this band’s A damningly fine protest eponymous first album. After more than 35 solo album with good melodies studio albums, The Godfather of Grunge is still on fire, raging against the System, the neocons, Rating: ÆÆÆÆ war, corruption, propaganda, censorship and the demise of human decency. Produced by Neil Young and Niko Bolas (The Volume Dealers) with co-producer L A Johnson. In this second part of an in-depth tribute to the Featured musicians: Neil Young (vocals, guitar, Canadian-born singer-songwriter, Michael harmonica and piano), Rick Bosas (bass guitar), Waddacor reviews Neil Young’s new album, Chad Cromwell (drums) and Tommy Bray explores his guitar playing, re-evaluates the (trumpet) with a choir led by Darrell Brown. overlooked classic album from 1974, On the Beach, and briefly revisits the 1990 grunge Songs: After the Garden / Living with War / The classic, Ragged Glory. This edition also lists the Restless Consumer / Shock and Awe / Families / Neil Young discography, rates his top albums Flags of Freedom / Let’s Impeach the President / and highlights a few pieces of trivia about the Lookin’ for a Leader / Roger and Out / America artist, his associates and his interests. -

Starr-Waterman American Popular Music Chapter 11: the 1970S: Rock Music, Disco, and the Popular Mainstream Key People Allman

Starr-Waterman American Popular Music Chapter 11: The 1970s: Rock Music, Disco, and the Popular Mainstream Key People Allman Brothers Band: Most important southern rock band of the late 1960s and early 1970s who reconnected the generative power of the blues to the mainstream of rock music. Barry White (1944‒2004): Multitalented African American singer, songwriter, arranger, conductor, and producer who achieved success as an artist in the 1970s with his Love Unlimited Orchestra; perhaps best known for his full, deep voice. Carlos Santana (b. 1947): Mexican-born rock guitarist who combined rock, jazz, and Afro-Latin elements on influential albums like Abraxas. Carole King (b. 1942): Singer-songwriter who recorded influential songs in New York’s Brill Building and later recorded the influential album Tapestry in 1971. Charlie Rich (b. 1932): Country performer known as the “Silver Fox” who won the Country Music Association’s Entertainer of the Year award in 1974 for his song “The Most Beautiful Girl.” Chic: Disco group who recorded the hit “Good Times.” Chicago: Most long-lived and popular jazz rock band of the 1970s, known today for anthemic love songs such as “If You Leave Me Now” (1976), “Hard to Say I’m Sorry” (1982), and “Look Away” (1988). David Bowie (1947‒2016): Glam rock pioneer who recorded the influential album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars in 1972. Dolly Parton (b. 1946): Country music star whose flexible soprano voice, songwriting ability, and carefully crafted image as a cheerful sex symbol combined to gain her a loyal following among country fans. -

THE BRILL BUILDING, 1619 Broadway (Aka 1613-23 Broadway, 207-213 West 49Th Street), Manhattan Built 1930-31; Architect, Victor A

Landmarks Preservation Commission March 23, 2010, Designation List 427 LP-2387 THE BRILL BUILDING, 1619 Broadway (aka 1613-23 Broadway, 207-213 West 49th Street), Manhattan Built 1930-31; architect, Victor A. Bark, Jr. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1021, Lot 19 On October 27, 2009 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation of the Brill Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark site. The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with provisions of law. Three people spoke in support of designation, including representatives of the owner, New York State Assembly Member Richard N. Gottfried, and the Historic Districts Council. There were no speakers in opposition to designation.1 Summary Since its construction in 1930-31, the 11-story Brill Building has been synonymous with American music – from the last days of Tin Pan Alley to the emergence of rock and roll. Occupying the northwest corner of Broadway and West 49th Street, it was commissioned by real estate developer Abraham Lefcourt who briefly planned to erect the world’s tallest structure on the site, which was leased from the Brill Brothers, owners of a men’s clothing store. When Lefcourt failed to meet the terms of their agreement, the Brills foreclosed on the property and the name of the nearly-complete structure was changed from the Alan E. Lefcourt Building to the, arguably more melodious sounding, Brill Building. Designed in the Art Deco style by architect Victor A. Bark, Jr., the white brick elevations feature handsome terra-cotta reliefs, as well as two niches that prominently display stone and brass portrait busts that most likely portray the developer’s son, Alan, who died as the building was being planned. -

Chicago Police and the Labor and Urban Crises of the Late Twentieth Century

The Patrolmen’s Revolt: Chicago Police and the Labor and Urban Crises of the Late Twentieth Century By Megan Marie Adams A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Robin Einhorn, Chair Professor Richard Candida-Smith Professor Kim Voss Fall 2012 1 Abstract The Patrolmen’s Revolt: Chicago Police and the Labor and Urban Crises of the Late Twentieth Century by Megan Marie Adams Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Robin Einhorn, Chair My dissertation uncovers a history of labor insurgency and civil rights activism organized by the lowest-ranking members of the Chicago police. From 1950 to 1984, dissenting police throughout the city reinvented themselves as protesters, workers, and politicians. Part of an emerging police labor movement, Chicago’s police embodied a larger story where, in an era of “law and order” politics, cities and police departments lost control of their police officers. My research shows how the collective action and political agendas of the Chicago police undermined the city’s Democratic machine and unionized an unlikely group of workers during labor’s steep decline. On the other hand, they both perpetuated and protested against racial inequalities in the city. To reconstruct the political realities and working lives of the Chicago police, the dissertation draws extensively from new and unprocessed archival sources, including aldermanic papers, records of the Afro-American Patrolman’s League, and previously unused collections documenting police rituals and subcultures. -

Popular Music, Stars and Stardom

POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM EDITED BY STEPHEN LOY, JULIE RICKWOOD AND SAMANTHA BENNETT Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN (print): 9781760462123 ISBN (online): 9781760462130 WorldCat (print): 1039732304 WorldCat (online): 1039731982 DOI: 10.22459/PMSS.06.2018 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design by Fiona Edge and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2018 ANU Press All chapters in this collection have been subjected to a double-blind peer-review process, as well as further reviewing at manuscript stage. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Contributors . ix 1 . Popular Music, Stars and Stardom: Definitions, Discourses, Interpretations . 1 Stephen Loy, Julie Rickwood and Samantha Bennett 2 . Interstellar Songwriting: What Propels a Song Beyond Escape Velocity? . 21 Clive Harrison 3 . A Good Black Music Story? Black American Stars in Australian Musical Entertainment Before ‘Jazz’ . 37 John Whiteoak 4 . ‘You’re Messin’ Up My Mind’: Why Judy Jacques Avoided the Path of the Pop Diva . 55 Robin Ryan 5 . Wendy Saddington: Beyond an ‘Underground Icon’ . 73 Julie Rickwood 6 . Unsung Heroes: Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown’s Funk Brothers . 95 Vincent Perry 7 . When Divas and Rock Stars Collide: Interpreting Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballé’s Barcelona .