Fertilizer Production, and Industrial Use – and Explores How Fuel Choices in These Sectors May Respond to a Range of Market and Policy Conditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamics of Governance and Development in India a Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar After 1990

RUPRECHT-KARLS-UNIVERSITÄT HEIDELBERG FAKULTÄT FÜR WIRTSCHAFTS-UND SOZIALWISSENSCHAFTEN Dynamics of Governance and Development in India A Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar after 1990 Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Dr. rer. pol. an der Fakultät für Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Erstgutachter: Professor Subrata K. Mitra, Ph.D. (Rochester) Zweitgutachter: Professor Dr. Dietmar Rothermund vorgelegt von: Seyedhossein Zarhani Dezember 2015 Acknowledgement The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the help of many individuals. I am grateful to all those who have provided encouragement and support during the whole doctoral process, both learning and writing. First and foremost, my deepest gratitude and appreciation goes to my supervisor, Professor Subrata K. Mitra, for his guidance and continued confidence in my work throughout my doctoral study. I could not have reached this stage without his continuous and warm-hearted support. I would especially thank Professor Mitra for his inspiring advice and detailed comments on my research. I have learned a lot from him. I am also thankful to my second supervisor Professor Ditmar Rothermund, who gave me many valuable suggestions at different stages of my research. Moreover, I would also like to thank Professor Markus Pohlmann and Professor Reimut Zohlnhöfer for serving as my examination commission members even at hardship. I also want to thank them for letting my defense be an enjoyable moment, and for their brilliant comments and suggestions. Special thanks also go to my dear friends and colleagues in the department of political science, South Asia Institute. My research has profited much from their feedback on several occasions, and I will always remember the inspiring intellectual exchange in this interdisciplinary environment. -

STATISTICAL REPORT GENERAL ELECTIONS, 2004 the 14Th LOK SABHA

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTIONS, 2004 TO THE 14th LOK SABHA VOLUME III (DETAILS FOR ASSEMBLY SEGMENTS OF PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES) ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India – General Elections, 2004 (14th LOK SABHA) STATISCAL REPORT – VOLUME III (National and State Abstracts & Detailed Results) CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. Part – I 1. List of Participating Political Parties 1 - 6 2. Details for Assembly Segments of Parliamentary Constituencies 7 - 1332 Election Commission of India, General Elections, 2004 (14th LOK SABHA) LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP Bharatiya Janata Party 2 . BSP Bahujan Samaj Party 3 . CPI Communist Party of India 4 . CPM Communist Party of India (Marxist) 5 . INC Indian National Congress 6 . NCP Nationalist Congress Party STATE PARTIES 7 . AC Arunachal Congress 8 . ADMK All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 9 . AGP Asom Gana Parishad 10 . AIFB All India Forward Bloc 11 . AITC All India Trinamool Congress 12 . BJD Biju Janata Dal 13 . CPI(ML)(L) Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) (Liberation) 14 . DMK Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 15 . FPM Federal Party of Manipur 16 . INLD Indian National Lok Dal 17 . JD(S) Janata Dal (Secular) 18 . JD(U) Janata Dal (United) 19 . JKN Jammu & Kashmir National Conference 20 . JKNPP Jammu & Kashmir National Panthers Party 21 . JKPDP Jammu & Kashmir Peoples Democratic Party 22 . JMM Jharkhand Mukti Morcha 23 . KEC Kerala Congress 24 . KEC(M) Kerala Congress (M) 25 . MAG Maharashtrawadi Gomantak 26 . MDMK Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 27 . MNF Mizo National Front 28 . MPP Manipur People's Party 29 . MUL Muslim League Kerala State Committee 30 . -

Application Employee of High Sr No

Application Employee of High Sr No. Seq No Rollno Applicant Full Name Father's Full Name Applicant Mother Name DOB (dd/MMM/yyyy) Domicile of State Category Sub_Category Email ID Gender Mobile Number Court Allahabad Is Present Score 1 1000125 2320015236 ANIL KUMAR SHIV CHARAN ARYA MAHADEVI 6/30/1990 Uttar Pradesh OBC Sports Person (S.P.)[email protected] Male 9911257770 No PRESENT 49 2 1000189 2320015700 VINEET AWASTHI RAM KISHOR AWASTHI URMILA AWASTHI 4/5/1983 Uttar Pradesh General NONE [email protected] 8423230100 No PRESENT 43 3 1000190 2110045263HEMANT KUMAR SHARMA GHANSHYAM SHARMA SHAKUNTALA DEVI 3/22/1988 Other than Uttar Pradesh General [email protected] 9001934082 No PRESENT 39 4 1000250 2130015960 SONAM TIWARI SHIV KUMAR TIWARI GEETA TIWARI 4/21/1991 Other than Uttar Pradesh General [email protected] Male 8573921039 No PRESENT 44 5 1000487 2360015013 RAJNEESH KUMAR RAJVEER SINGH VEERWATI DEVI 9/9/1989 Uttar Pradesh SC NONE [email protected] Male 9808520812 No PRESENT 41 6 1000488 2290015053 ASHU VERMA LATE JANARDAN LAL VERMA PADMAVATI VERMA 7/7/1992 Uttar Pradesh SC NONE [email protected] Male 9005724155 No PRESENT 36 7 1000721 2420015498 AZAJUL AFZAL MOHAMMAD SHAHID NISHAD NAZMA BEGUM 2/25/1985 Uttar Pradesh General NONE [email protected] 7275529796 No PRESENT 27 8 1000794 2250015148AMBIKA PRASAD MISHRA RAM NATH MISHRA NIRMALA DEVI 12/24/1991 Uttar Pradesh General NONE [email protected] Male 8130809970 No PRESENT 36 9 1001008 2320015652 SATYAM SHUKLA PREM PRAKASH -

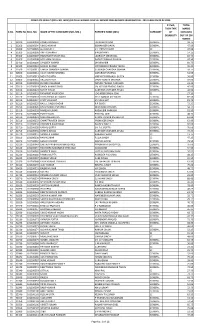

Result (Roll No

COMPLETE RESULT (ROLL NO. WISE) OF DELHI HIGHER JUDICIAL SERVICE PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION - 2019 HELD ON 02.02.2020 IF PwD, TOTAL THEN TYPE MARKS S.NO. FORM No. ROLL NO. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE (MR./MS.) FATHER'S NAME (MR.) CATEGORY OF OBTAINED DISABILITY OUT OF 200 MARKS 1 33100 101200002 PANKAJ PRABHAT JAGDISH PRASAD GENERAL 32.75 2 33200 101200004 VINOD KUMAR BISHAMBER DAYAL GENERAL 47.50 3 30300 101200005 GURUMUKH SH. PREM CHAND SC 47.00 4 31300 101200006 ANITA SHARMA B N SHARMA GENERAL 14.25 5 33300 101200007 HARVINDER SINGH GILL JAGROOP SINGH GILL GENERAL 82.75 6 31400 101200008 NEELMANI SHUKLA RADHEY RAMAN SHUKLA GENERAL 47.50 7 32400 101200009 SANDEEP KUMAR DHARAMBIR GENERAL 60.75 8 31500 101200010 NAWIN KUMAR VIDYANAND PRASAD YADAV GENERAL 45.25 9 33500 101200011 UMESH CHANDRA SAXENA SUBHASH CHANDRA SAXENA GENERAL 59.75 10 30600 101200012 VIJAY KUMAR SHARMA DATARAM SHARMA GENERAL 51.50 11 32600 101200013 MOHIT GUPTA VIRENDER PRAKASH GUPTA GENERAL 56.00 12 30800 101200015 ARUJ MATHUR VINAY KUMAR MATHUR GENERAL 59.00 13 31010 101200018 EUREKA CHAUHAN NANDU PRASAD CHAUHAN GENERAL 22.25 14 32010 101200019 SANOJ KUMAR SINGH LAL KISHOR PRASAD SINGH GENERAL 45.00 15 30110 101200021 SUMIT AHUJA SUBHASH CHANDER AHUJA GENERAL 42.50 16 31110 101200022 RAMANJIT KAUR SOHI JOGINDER SINGH SOHI SC 27.50 17 32110 101200023 SYED ZISHAN ALI WARSI SYED QAMAR ALI WARSI GENERAL 82.50 18 33110 101200024 JYOTI VASHISHT SN VASHISHT GENERAL 81.75 19 31210 101200025 RAHUL SINGH DAGAR R P SINGH GENERAL 72.25 20 33210 101200026 KHUSHVINDER SHARMA DEVENDER SHARMA GENERAL 58.75 21 31310 101200028 NARESH KUMAR RAGHUBIR PARKASH GENERAL 81.50 22 32310 101200029 PUNEET JAIN PINK RAJ JAIN GENERAL 48.75 23 32410 101200031 NIDHI MEHROTRA KAMAL KUMAR MEHROTRA GENERAL 62.00 24 31510 101200032 CHHATTRAVEER SINGH PREMVEER SINGH GENERAL 62.00 25 30710 101200034 HERINDER KAUR BRAR BALDEV SINGH GENERAL 92.00 26 31710 101200035 KAMAL GUPTA SH. -

Dated: 19.03.2021 Result of Senior Resident Written Examination Held

भारत सरकार GOVERNMENT OF INDIA चिचकत्सा अचिक्षक का कार्ाालर् OFFICE OF MEDICAL SUPERINTENDENT सफदरजंग अस्पताल एंव वी.एम.एम.कॉलᴂज SAFDARJUNG HOSPITAL & V.M.M.C. नई चदल्ली – 110029 NEW DELHI - 110029 Dated: 19.03.2021 Result of Senior Resident Written Examination held in March, 2021 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES FOR INTERVIEW All eligible candidates must report for interview at 9 AM in Room No. 14, Academic Section, VMMC Building, on the scheduled day of the interview. The candidates must bring all original certificates/documents for the candidature of the post as stated in the Advertisement for verification on the day of their interview along with NOC from present employer, if any. It is further reiterated that selected candidates will not be allowed to join without production of registration with Delhi Medical Council /Delhi Dental Council with MBBS /BDS & PG qualification. OBC certificate issued on or after 01.04.2020 in the prescribed format for Central Government job as per DOPT O.M. No. 36036/2/2013-Estt.(Res.) dated 30.05.2014. EWS certificate issued by the competent authority in the prescribed format for Central Government job as per DOPT O.M. No. 36039/1/2019-Estt. (Res.) dated 31.01.2019. Dates for Interview for recruitment of Senior Residents are as follows SN Department/Speciality Reporting Date & Time 1. ANAESTHESIA 01-04-2021 (Thursday) at 09:00 AM onwards 2. ANATOMY 05-04-2021 (Monday) at 09:00 AM onwards 3. BIOCHEMISTRY 05-04-2021 (Monday) at 09:00 AM onwards 4. -

Curriculumvitae–May, 2015

CurriculumVitae–May, 2015 ASHUTOSH SHARMA E-Mail: [email protected] Mobile: +91-9540739759 Integrated Research and Action for Development (IRADe) Shivalik, C-80 New Delhi-110017 PERSONAL INFORMATION Date of Birth: February12, 1983 Sex: Male Marital Status: Unmarried Nationality: Indian EDUCATION 2013 Ph.D.in Economics, UniversityofMumbai. Thesis Title: Growth and Cycles in India: 1951-2006. Principal Advisor: Professor Neeraj Hatekar 2013 UGC-NET Qualified 2007 M.A. inEconomics, GokhaleInstitute ofPolitics andEconomics. First Class 2004 B.A. Economics (Honours).Magadh University. First Class. FIELDS OFCONCENTRATION Development Economics, Agriculture Economics, Gender Energy and Climate Change, Macroeconomics. PROFESSIONAL ENGAGEMENT August, 2013-Present IRADe, New Delhi Senior Research Analyst Dec, 2011-June, 2013 NIIT University Assistant Professor of Economics Jun,2007-Dec,2011 Manager Reliance Retail Subsidiary company 1 SOFTWARE AND DATA SET SKILL Software: Proficient in SPSS, R and E-views Data Set : NSSO, Census, NFHS, DLHS and Primary Survey SELECTED PUBLICATIONS “India's Growth Experience and the Missing Transition”, with Neeraj Hatekar, ArthaVijnana, Vol. LIV,NO.2, 2012, 115-137. “What Drives Inflation in India: Overheating or Input Costs?”with Neeraj Hatekar and Savita Kulkarni, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. XLVI,NO.34,2011, 46-51. “Causality between Prices, Output and MoneyinIndia:An Empirical Investigation in the Frequency Domain”, with Neeraj Hatekar and AbodhKumar, published in 2011, working paper of Society for Policy Modelling, http://www.econmodels.com/public/dbArticles.php. “Interpreting the Relation of Money, Output and Prices in India(1991:2008)”, Journal of the Indian School of Political Economy, Vol. XX, July-September2008,497-511. “Intrahousehold Gender Representation and Maternal Health Care in Rural India " with Rucha Joshi and Chandrashekhar Singh (submitted in EPW). -

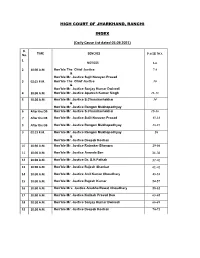

Daily Cause List Dated 03.09.2021)

HIGH COURT OF JHARKHAND, RANCHI INDEX (Daily Cause List dated 03.09.2021) Sl. TIME BENCHES No. PAGE NO. 1 NOTICES 1-6 2 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble The Chief Justice 7-9 & Hon’ble Mr. Justice Sujit Narayan Prasad 3 02:15 P.M. Hon’ble The Chief Justice 10 & Hon’ble Mr. Justice Sanjay Kumar Dwivedi 4 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Aparesh Kumar Singh 11-13 5 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice S.Chandrashekhar 14 & Hon’ble Mr. Justice Rongon Mukhopadhyay 6 After the DB Hon’ble Mr. Justice S.Chandrashekhar 15-16 7 After the DB Hon’ble Mr. Justice Sujit Narayan Prasad 17-22 8 After the DB Hon’ble Mr. Justice Rongon Mukhopadhyay 23-27 9 02:15 P.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Rongon Mukhopadhyay 28 & Hon’ble Mr. Justice Deepak Roshan 10 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Ratnaker Bhengra 29-30 11 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Ananda Sen 31-36 12 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Dr. S.N.Pathak 37-40 13 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Rajesh Shankar 41-42 14 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Anil Kumar Choudhary 43-53 15 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Rajesh Kumar 54-57 16 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mrs. Justice Anubha Rawat Choudhary 58-62 17 10:30 A.M. Hon’ble Mr. Justice Kailash Prasad Deo 63-65 18 10:30 A.M. -

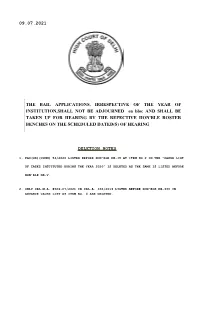

09.07.2021 Deletion Notes the Bail Applications

09.07.2021 THE BAIL APPLICATIONS, IRRESPECTIVE OF THE YEAR OF INSTITUTION,SHALL NOT BE ADJOURNED en bloc AND SHALL BE TAKEN UP FOR HEARING BY THE REPECTIVE HON'BLE ROSTER BENCHES ON THE SCHEDULED DATED(S) OF HEARING DELETION NOTES 1. FAO(OS)(COMM) 53/2020 LISTED BEFORE HON'BLE DB-IV AT ITEM NO 2 IN THE “CAUSE LIST OF CASES INSTITUTED DURING THE YEAR 2020” IS DELETED AS THE SAME IS LISTED BEFORE HON'BLE DB-V. 2. ONLY CRL.M.A. 8506-07/2021 IN CRL.A. 355/2019 LISTED BEFORE HON'BLE DB-III IN ADVANCE CAUSE LIST AT ITEM NO. 4 ARE DELETED. HIGH COURT OF DELHI AT NEW DELHI No.289/RG/DHC/2021 Dated: 23-04-2021 O FFICE ORD ER In continuation of this Court's Office Order No.4/RG/DHC/2021 dated 23.4.2021, it is further directed that in view of the prevailing circumstances, wherever so required, the concerned Counsel or party-in-person may,at the time of filing any petition, etc., submit an application seeking exemption from filing sworn/affirmed affidavit(s). Sd/- (MANOJ JAIN) REGISTRAR GENERAL STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE (SOP) FOR RESUMPTION OF PHYSICAL FUNCTIONING IN THE HIGH COURT OF DELHI W.E.F. 01.09.2020 09.07.2021 1 ADVANCE CAUSE LIST OF CASES (APPLT. SIDE) MATTERS LISTED FOR 09.07.2021 DIVISION BENCH-I HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MS.JUSTICE JYOTI SINGH [NOTE: IN CASE ANY ASSISTANCE REGARDING VIRTUAL HEARING IS REQUIRED, PLEASE CONTACT, MR. VIJAY RATTAN SUNDRIYAL (PH: 9811136589) COURT MASTER & MR. -

31.07.2020 J- 1 Pronouncement of Judgement (Applt

31.07.2020 J- 1 PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGEMENT (APPLT. JURISDICTION) HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE SURESH KUMAR KAIT AT 10:30 A.M. 1. CRL.M.C. 1525/2020 ISHRAT JAHAN LALIT VALECHA, MANU PRABHAKAR, CRL.M.A. 9386/2020 VS. STATE TUSHAR ANAND, ABHINAV MEENA, RAHUL MEHRA, AMIT CHADHA, AMIT MAHAJAN, AMIT PRASAD, HIGH COURT OF DELHI REGISTRAR(LISTING) 30.07.2020 31. 07. 2020 * 1 CAUSE LIST ** HIGH COURT OF DELHI: NEW DELHI No.119/RG/DHC/2020 Dated: 22.04.2020 OFFICE ORDER As per the directions of Hon’ble the Chief Justice, on the recommendations of the Hon’ble Information Technology Committee, and in view of the directions passed by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the case of Suo Motu Writ (Civil) No.5/2020 dated 6th April 2020 titled “Re: Guidelines for Court Functioning Through Video Conferencing During Covid-19 Pandemic”, this Court has started a Helpline Number “14611” to receive any complaint with regard to deficiency in visual acuity or audibility experienced by participants during the video conferencing proceedings. The helpline number will be manned by the officer nominated by the Registrar (IT) for receiving of any complaint, who, in turn, will communicate the same to the Court Master(s) of the concerned Bench. To facilitate lodgement of complaints the Listing Branch shall provide in the cause list, in addition to the helpline number, the mobile number of the court master of the concerned Bench. Furthermore, the cause list will indicate that no grievance will be entertained with regard to connectivity, quality or otherwise, after the video conferencing proceedings are over, save and except, where directions are passed by the concerned Bench to entertain such complaints post conclusion of video conferencing proceedings. -

10. 08. 2020 * 1 Cause List

10. 08. 2020 * 1 CAUSE LIST HIGH COURT OF DELHI: NEW DELHI No.119/RG/DHC/2020 Dated: 22.04.2020 OFFICE ORDER As per the directions of Hon’ble the Chief Justice, on the recommendations of the Hon’ble Information Technology Committee, and in view of the directions passed by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the case of Suo Motu Writ (Civil) No.5/2020 dated 6th April 2020 titled “Re: Guidelines for Court Functioning Through Video Conferencing During Covid-19 Pandemic”, this Court has started a Helpline Number “14611” to receive any complaint with regard to deficiency in visual acuity or audibility experienced by participants during the video conferencing proceedings. The helpline number will be manned by the officer nominated by the Registrar (IT) for receiving of any complaint, who, in turn, will communicate the same to the Court Master(s) of the concerned Bench. To facilitate lodgement of complaints the Listing Branch shall provide in the cause list, in addition to the helpline number, the mobile number of the court master of the concerned Bench. Furthermore, the cause list will indicate that no grievance will be entertained with regard to connectivity, quality or otherwise, after the video conferencing proceedings are over, save and except, where directions are passed by the concerned Bench to entertain such complaints post conclusion of video conferencing proceedings. By Order Sd/- (Manoj Jain) Registrar General HIGH COURT OF DELHI, NEW DELHI No. R-340/RG/DHC/2020 Dated : 25.05.2020 CIRCULAR SUBJECT: Contacting Court Masters for the limited purpose only. On account of outbreak of COVID-19, regular functioning of this court remains suspended and hearing of urgent matters is presently restricted only to videoconferencing. -

Election Commission of India State Elections - 2005 List of Contesting Candidates

Election Commission of India State Elections - 2005 List of Contesting Candidates Candidate Candidate Party Symbol Votes Status Sl.No Name Abbreviation Polled State Name: Bihar AC No & Name: 1-Dhanaha(GEN) 1 ARTHRAJ YADAV BSP Elephant 2893 Forfeited 2 INDRAJIT YADAV NCP Clock 2985 Forfeited 3 RAGHUNATH PRASAD SAHANI JD(U) Arrow 1716 Forfeited 4 RAJESH SINGH RJD Hurricane 19389 won Lamp 5 ARUN KUMAR TIWARI LJP Bungalow 5073 Forfeited 6 KRISHNA BIHARI PRASAD KUSHWAHA NLP Lock and Key 1848 Forfeited 7 BAWWAN PRASAD YADAV SAP Flaming Torch 3320 Forfeited 8 BAL KHILA THAKUR CPI(ML)(L) Flag with 844 Forfeited Three Stars 9 RAMADHAR YADAV SP Bicycle 13287 Runner-up 10 MANOJ PRASAD IND Envelope 1067 Forfeited 11 MUKESH KUMAR KUSHWAHA IND Cot 10865 Lost AC No & Name: 2-Bagha(SC) 1 DINANATH RAM BSP Elephant 3487 Forfeited 2 NARESH RAM RJD Hurricane 27481 Runner-up Lamp 3 PURNAMASI RAM JD(U) Arrow 59151 won 4 CHHOTE LAL RAM CPI(ML)(L) Flag with 1503 Forfeited Three Stars 5 RAMBHA DEVI LJP Bungalow 3384 Forfeited 6 RAM PRAWESH RAM RLD Aeroplane 1997 Forfeited 7 SUGRIM RAM SHS Axe 1159 Forfeited 8 SURESH RAM SP Bicycle 16175 Forfeited 9 DINESH CHANDRA RAM IND Lock and Key 1355 Forfeited 10 RAMASHANKAR BHAGAT IND Sewing 1554 Forfeited Machine 11 RAMASHISH BAITHA IND Book 1098 Forfeited 12 VISHWANATH RAM IND Letter Box 2393 Forfeited AC No & Name: 3-Ramnagar(GEN) 1 ARJUN VIKRAM SHAH INC Hand 4218 Forfeited 2 CHANDRA MOHAN RAI BJP Lotus 20961 won 3 PRABHAT RANJAN SINGH BSP Elephant 11180 Forfeited Page 1 of Page < 1 > of 171 Candidate Candidate Party Symbol Votes Status Sl.No Name Abbreviation Polled 4 RAM PRASAD YADAV RJD Hurricane 16377 Lost Lamp 5 MD. -

2018 NIC BALLIA 8-10-18 (5128).Xlsx

DPR for Ballia, ULB– Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana BLC-(N) (Urban) 2018 WARD S.N CANDIDATE NAME Caste F/H NAME AGE NO. ADDRESS 1 03 AAASHIM KHATOON 4 MAIHARDDIN KURAISHI 43 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 2 15 AAYASH KHATOON 4 SAKIL AHAMAD 25 RAJENDRA NAGAR ,BALLIA 3 03 ABDUL GAFFAR ANSARI 4 NABBI RASUL 64 KASABTOLA KAJIPURA BALLIA 4 03 ABDUL MAJID 4 ABDUL SAKUR 38 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 5 03 ABDUL RAHEEM 4 NABI RASOOL 50 KASABTOLA KAJIPURA BALLIA 6 14 ABHAY KUMAR 4 JAYRAM 28 RAJPUT NEWARI,BALLIA 7 11 ABHAY KUMAR YADAV 4 VIJAYMAL YADAV 35 MUHAMMADPUR BALLIA 8 13 ABHISHEK KUUMAR SINGH 4 KASHI NATH SINGH 35 TAIGORE NAGAR JEL KE PEECHE 9 11 ADITYA PRASAD KANU 4 VISHWANATH 66 GANDHI NAGAR CHITBARAGAON 10 11 AFASANA KHATOON 1 YUNUSH ANSHARI 26 BAHERI BALLIA 11 03 AFROJ ALI ANSARI 4 MOHAMMAD GAFFAR 37 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 12 16 AFTAB ALAM 4 MD. HABIB 45 RAJPUT NEWARI BALLIA 13 03 AJAM KURAISHI 4 HASIM KURASHI 53 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 14 13 AJAY KUMAR KHARWAR 1 HAR RAM KHARWAR 18 RAMPUR UDDYABHAN NAI BASTI BALLA 15 11 AJAY KUMAR YADAV 4 RAM VILASH YADAV 36 VAJEERAPUR CHANDANPUR BALLIA 16 07 AJAY PASWAN 1 BHARAT PASWAN 31 PURANI BASTI 17 11 AJAY PASWAN 1 SHIV NATH RAM 21 KRISHNA NAGAR, BALLIA 18 11 AJAY YADAV 4 DOMAN YADAV 45 KRISHNA NAGAR KANSHPUR BALLIA 19 13 AJEET KUMAR 4 HARERAM PRASAD 34 RAMPUR UDDYABHAN NAI BASTI BALLA 20 11 AJEET YADAV 4 PARSHURAM YADAV 34 JAPLINGANJ YADAV NAGAR BALLIA 21 03 AKHTAR ALI ANSARI 1 MD JABBAR ASNARI 35 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 22 03 AKHTAR ALI ANSARI 1 NURUL HASAN 59 KAZIPURA ISLAMABAD BALLILA 23 AKHTARI