Comments of the Maine Attorney General

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

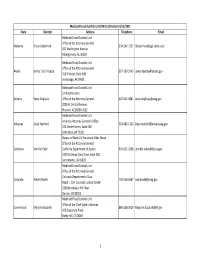

Medicaid Fraud Control Unit (MFCU) Directors 4/15/2021

Medicaid Fraud Control Unit (MFCU) Directors 4/15/2021 State Director Address Telephone Email Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Attorney General Alabama Bruce Lieberman 334‐242‐7327 [email protected] 501 Washington Avenue Montgomery, AL 36130 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Attorney General Alaska James "Jay" Fayette 907‐269‐5140 [email protected] 310 K Street, Suite 308 Anchorage, AK 99501 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Criminal Division Arizona Steve Duplissis Office of the Attorney General 602‐542‐3881 [email protected] 2005 N. Central Avenue Phoenix, AZ 85004‐1592 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Arkansas Attorney General's Office Arkansas Lloyd Warford 501‐682‐1320 [email protected] 323 Center Street, Suite 200 Little Rock, AR 72201 Bureau of Medi‐Cal Fraud and Elder Abuse Office of the Attorney General California Jennifer Euler California Department of Justice 916‐621‐1858 [email protected] 2329 Gateway Oaks Drive, Suite 200 Sacramento, CA 95833 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Attorney General Colorado Department of Law Colorado Robert Booth 720‐508‐6687 [email protected] Ralph L. Carr Colorado Judicial Center 1300 Broadway, 9th Floor Denver, CO 80203 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Chief State's Attorney Connecticut Marjorie Sozanski 860‐258‐5929 [email protected] 300 Corporate Place Rocky Hill, CT 06067 1 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit (MFCU) Directors 4/15/2021 State Director Address Telephone Email Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Attorney General Delaware Edward Black (Acting) 302‐577‐4209 [email protected] 820 N French Street, 5th Floor Wilmington, DE 19801 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit District of Office of D.C. -

Expressions of Legislative Sentiment Recognizing

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from electronic originals (may include minor formatting differences from printed original) Senate Legislative Record One Hundred and Twenty-Sixth Legislature State of Maine Daily Edition First Regular Session December 5, 2012 - July 9, 2013 First Special Session August 29, 2013 Second Regular Session January 8, 2014 - May 1, 2014 First Confirmation Session July 31, 2014 Second Confirmation Session September 30, 2014 pages 1 - 2435 SENATE LEGISLATIVE RECORD Senate Legislative Sentiment Appendix Cheryl DiCara, of Brunswick, on her retirement from the extend our appreciation to Mr. Seitzinger for his commitment to Department of Health and Human Services after 29 years of the citizens of Augusta and congratulate him on his receiving this service. During her career at the department, Ms. DiCara award; (SLS 7) provided direction and leadership for state initiatives concerning The Family Violence Project, of Augusta, which is the the prevention of injury and suicide. She helped to establish recipient of the 2012 Kennebec Valley Chamber of Commerce Maine as a national leader in the effort to prevent youth suicide Community Service Award. The Family Violence Project provides and has been fundamental in uniting public and private entities to support and services for survivors of domestic violence in assist in this important work. We send our appreciation to Ms. Kennebec County and Somerset County. Under the leadership of DiCara for her dedicated service and commitment to and Deborah Shephard, the Family Violence Project each year compassion for the people of Maine, and we extend our handles 4,000 calls and nearly 3,000 face to face visits with congratulations and best wishes to her on her retirement; (SLS 1) victims at its 3 outreach offices and provides 5,000 nights of Wild Oats Bakery and Cafe, of Brunswick, on its being safety for victims at its shelters. -

To: Commission From: Jonathan Wayne, Executive Director Michael Dunn, Esq., Political Committee and Lobbyist Registrar Date: May 20, 2020 Re: Request by Mr

Commission Meeting 05/27/2020 STATE OF MAINE Agenda Item #2 COMMISSION ON GOVERNMENTAL ETHICS AND ELECTION PRACTICES 135 STATE HOUSE STATION AUGUSTA, MAINE 04333-0135 To: Commission From: Jonathan Wayne, Executive Director Michael Dunn, Esq., Political Committee and Lobbyist Registrar Date: May 20, 2020 Re: Request by Mr. John Jamieson to Investigate Polling by U.S. Senator Susan Collins Maine Election Law regulates funds, goods and services (e.g., polling) received by someone for the purpose of deciding whether to become a candidate for state office. If the person subsequently runs for office, the candidate must disclose the funds, goods and services as contributions in their first campaign finance report. They are subject to the same dollar amount limitations as contributions received after the individual becomes a candidate. The person must also disclose any payments made for the purpose of deciding whether to become a candidate. In 2017, U.S. Senator Susan Collins was giving consideration to running for Governor of Maine. Mr. John Jamieson of South Portland requests that the Commission investigate whether she received polling services that exceeded the $1,600 limitation applicable at that time. Sen. Collins responds that the polling was paid for by Collins for Senate (her U.S. Senate re-election committee) for a federal campaign purpose and she did not violate Maine Election Law. LEGAL REQUIREMENTS Standard for Opening a Requested Investigation The Election Law authorizes the Commission to receive requests for investigation and to conduct an investigation “if the reasons stated for the request show sufficient grounds for believing that a violation may have occurred”: A person may apply in writing to the commission requesting an investigation as described in subsection 1. -

Craig Boundy Chief Executive Officer Experian 475 Anton Blvd. Costa Mesa, CA 92626 Christopher A. Cartwright President And

STATE OF NEW YORK STATE OF PENNSYLVANIA OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL LETITIA JAMES JOSH SHAPIRO ATTORNEY GENERAL ATTORNEY GENERAL April 28, 2020 Craig Boundy Chief Executive Officer Experian 475 Anton Blvd. Costa Mesa, CA 92626 Christopher A. Cartwright President and Chief Executive Officer TransUnion LLC 555 West Adams Street Chicago, IL 60661 Mark W. Begor Chief Executive Officer Equifax Information Services, LLC 1550 Peachtree Street, N.W. Atlanta, GA 30309 Dear Mr. Boundy, Mr. Cartwright, and Mr. Begor: We, the undersigned Attorneys General of New York, Pennsylvania, California, Colorado, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Virginia, Washington, Wisconsin and the District of Columbia, write to remind the consumer reporting agencies (“CRAs”) of their continuing obligation during the COVID-19 crisis to comply with the protections contained in the Fair Credit Reporting Act (“FCRA”); state laws governing credit- reporting; and our offices’ agreements with the CRAs. In this period of economic turmoil, these consumer protections are more important than ever. While the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s recent announcement suggests that it will not enforce the FCRA’s 30- or 45-day deadline to investigate consumer disputes requirements during the COVID-19 crisis,1 the undersigned state Attorneys General are committed to protecting consumers in our states and will continue to enforce all federal and state requirements during this crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in significant economic disruption. Across the nation, businesses are closing, and millions of workers face lost wages or unemployment. -

Consumer Assistance Resources

Last revised: 02/092/2004 31 CONSUMER ASSISTANCE RESOURCES § 31. 1. Introduction This Consumer Law Guide Appendix describes the different consumer assistance resources, state and national, that are available to Maine Consumers. It contains the following sections: § 31. 2. Telephone Referral By Subject Matter § 31. 3 State Regulatory And Licensing Boards § 31. 4. National Attorney General Consumer Protection Contacts § 31. 5 United States Postal Inspectors, By Region § 31. 6 Maine District Attorneys (for complaints about criminal consumer fraud) § 31. 7. Maine District Courts, By County (Small Claims Court is part of the District Court) § 31. 8 Maine Law Libraries MAINE CONSUMER LAW GUIDE 31 - 2 § 31. 2. Telephone Referrals By Subject Matter SUBJECTS: A D. Home Financing Maine N. Abandoned Property Dangerous Products Home Heating National Attorney General Adult Protective Services Day Care National Consumer Orgs Agriculture Homeland Security Nursing Homes Airlines Debt Collections Hotels_Inns_Motels Nursing_Boarding Home Ombudsman Animals Health & Industry Disabled Housing O. Antitrust Discrimination Human Services Odometers Appliances District Attorneys I. P. Asbestos Do Not Call Information Identity Theft Pawn Shops Attorney General Door to Door Sellers Inns/Hotels/Motels Postal Inspector Autos (Motor Vehicles) E. Insulation Public Safety Economic Development Insurance Public Utilities Elderly Internet Public Advocate (PUC) Electric & Gas Bills Investments / Securities Q. Banking Electricians J. R. Bankruptcy Emergency Help Judges (complaints against) Real Estate Barbers Employment K. Beano/Games of Chance Energy S. Blue Cross/Blue Shield F. L. Securities Broker / Mortgage Federal Bureau- Labor Problems Small Claims Courts Investigation Business - Complaints Federal Communications Law Libraries Social Security Commission Business - Licensing Federal Trade Commission Lawyers / Legal Assistance State Licensing Boards Business – Questions Fire Marshall Lead Poisoning T. -

June 18, 2021 Honorable Merrick B. Garland Attorney General of The

DANA NESSEL MICHIGAN ATTORNEY GENERAL June 18, 2021 Honorable Merrick B. Garland Attorney General of the United States U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20530-0001 Lisa O. Monaco Deputy Attorney General U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20530-0001 Re: Department of Justice’s interpretation of Wire Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1084 Dear Attorney General Garland and Deputy Attorney General Monaco: We, the undersigned State Attorneys General, are seeking clarity and finality from the Department of Justice regarding its interpretation of the Wire Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1084. As you may be aware, 25 State Attorneys General wrote to your predecessors on March 21, 2019 to express our strong objection to the Office of Legal Counsel’s (OLC’s) Opinion “Reconsidering Whether the Wire Act Applies to Non- Sports Gambling,” which reversed the Department’s seven-year-old position that the Wire Act applied only to sports betting. Many States relied on that former position to allow online gaming to proceed. Since that letter, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit upheld a challenge to the new OLC Opinion, holding that the Wire Act applies only to sports betting. After the First Circuit decision, it is vital that States get clarity on the Department’s position going forward. States and industry participants need to understand what their rights are under the law without having to file suit in every federal circuit, and finality is needed so the industry may confidently invest in new products and features without fear of criminal prosecution. -

Letters to the U.S. House and U.S. Senate

April 29, 2021 Senator Patrick Leahy Senator Richard Shelby Chair Ranking Member U.S. Senate Committee U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations on Appropriations 437 Russell Building 304 Russell Building Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Senator Jeanne Shaheen Senator Jerry Moran Chair Ranking Member U.S. Senate Committee on U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations Appropriations Subcommittee on Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science, Commerce, Justice, Science, & Related Agencies & Related Agencies 506 Hart Building 521 Dirksen Building Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Re: State Attorneys General Support the Legal Services Corporation Dear Chair DeLauro, Ranking Member Granger, Chair Cartwright, and Ranking Member Aderholt, As state attorneys general, we respectfully request that you consider robust funding for the Legal Services Corporation (LSC) in the Fiscal Year 2022 Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations bill. Since 1974, LSC funding has provided vital and diverse legal assistance to low-income Americans including victims of natural disasters, survivors of domestic violence, families facing foreclosure, and veterans accessing earned benefits. Today, LSC also provides essential support for struggling families affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. As the single largest funder of civil legal aid in the United States, LSC-funded programs touch every corner of our country with more than 800 offices and a presence in every congressional district. LSC funding has also fostered public-private partnerships between legal aid organizations and private firms and attorneys across the country which donate their time and skills to assist residents in need. Nationwide, 132 independent nonprofit legal aid programs rely on this federal funding to provide services to nearly two million of our constituents on an annual basis. -

November 13, 2020 Via E-Mail and U.S. Mail the Honorable William

November 13, 2020 Via E-mail and U.S. Mail The Honorable William Barr U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 [email protected] [email protected] Dear Attorney General Barr: The 2020 election is over, and the people of the United States have decisively chosen a new President. It is in this context that we express our deep concerns about your November 9 memorandum entitled “Post-Voting Election Irregularity Inquiry.” As the chief legal and law enforcement officers of our respective states, we recognize and appreciate the U.S. Department of Justice’s (DOJ) important role in some instances in prosecuting criminal election fraud. Yet we are alarmed by your reversal of long-standing DOJ policy that has served to facilitate that function without allowing it to interfere with election results or create the appearance of political involvement in elections. Your directive to U.S. Attorneys this week threatens to upset that critical balance, with potentially corrosive effects on the electoral processes at the heart of our democracy. State and local officials conduct our elections. Enforcement of the election laws falls primarily to the states and their subdivisions. If there has been fraud in the electoral process, the perpetrators should be brought to justice. We are committed to helping to do so. But, so far, no plausible allegations of widespread misconduct have arisen that would either impact the outcome in any state or warrant a change in DOJ policy. For 40 years, the Department of Justice has followed a policy that recognizes the states’ principal responsibility for overseeing the election process. -

Case 3:20-Cv-03005 Document 1 Filed 05/01/20 Page 1 of 29

Case 3:20-cv-03005 Document 1 Filed 05/01/20 Page 1 of 29 1 XAVIER BECERRA LETITIA JAMES Attorney General of California Attorney General of the State of New York 2 SARAH E.MORRISON PHILIP BEIN ERIC KATZ Senior Counsel 3 Supervising Deputy Attorneys General TIMOTHY HOFFMAN* CATHERINE M.WIEMAN, SBN 222384 Senior Counsel 4 TATIANA K.GAUR, SBN 246227 Office of the Attorney General ROXANNE J.CARTER, SBN 259441 Environmental Protection Bureau 5 JESSICA BARCLAY-STROBEL, SBN 280361 28 Liberty Street BRYANT B. CANNON, SBN 284496 New York, NY 10005 6 Deputy Attorneys General Telephone: (716) 853-8465 300 South Spring Street, Suite 1702 Fax: (716) 853-8579 7 Los Angeles, CA 90013 Email: [email protected] Telephone: (213) 269-6329 Attorneys for Plaintiff State of New York 8 Fax: (916) 731-2128 E-mail: [email protected] 9 Attorneys for Plaintiff State of California, by and through Attorney General Xavier Becerra and 10 California State Water Resources Control Board [Additional Parties and Counsel Listed on 11 Signature Page] 12 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 13 FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 14 STATE OF CALIFORNIA BY AND THROUGH Case No. ATTORNEY GENERAL XAVIER BECERRA AND 15 CALIFORNIA STATE WATER RESOURCES COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY CONTROL BOARD, STATE OF NEW YORK, AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF 16 STATE OF CONNECTICUT, STATE OF ILLINOIS, STATE OF MAINE, STATE OF MARYLAND,STATE 17 OF MICHIGAN, STATE OF NEW JERSEY, STATE (Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. § OF NEW MEXICO, STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA 551 et seq.) 18 EX REL. -

1 in the Circuit Court of The

IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE SEVENTEENTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT, IN AND FOR BROWARD COUNTY, FLORIDA OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL, ) STATE OF FLORIDA, ) DEPARTMENT OF LEGAL AFFAIRS, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) vs. ) Court Case Number: ) UBER TECHNOLOGIES, INC. ) ) Defendant. ) FINAL JUDGMENT AND CONSENT DECREE Plaintiff Office of Attorney General, State of Florida, Department of Legal Affairs, by Pamela Jo Bondi, Attorney General of the State of Florida (hereinafter referred to as the “State of Florida”) has filed a Complaint for a permanent injunction and other relief in this matter pursuant to the Florida Deceptive and Unfair Trade Practices Act, Chapter 501, Part II, Florida Statutes (2018) (“FDUTPA”) and the Florida Information Protection Act, Section 501.171, Florida Statutes (2018) (“FIPA”), alleging Defendant UBER TECHNOLOGIES, INC. (“UBER”) committed violations of FDUTPA and FIPA. Plaintiff and UBER have agreed to the Court’s entry of this Final Judgment and Consent Decree without trial or adjudication of any issue of fact or law, and without admission of any facts alleged or liability of any kind. Preamble The Attorneys General of the states and commonwealths of Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, 1 Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii1, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland2, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah3, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming, and the District of Columbia (collectively, the “Attorneys General,” or the “States”) conducted an investigation under their respective State Consumer Protection Acts and Personal Information Protection Acts4 regarding the data breach involving UBER that occurred in 2016 and that UBER announced in 2017. -

This Assurance of Voluntary Compliance (The "Assurance") 1 Is Between Nationwide

In Re: NATIONWIDE MUTUAL INSURANCE COMP ANY and ALLIED PROPERTY & CASUALTY INSURANCE COMPANY ASSURANCE OF VOLUNTARY COMPLIANCE This Assurance of Voluntary Compliance (the "Assurance") 1 is between Nationwide Mutual Insurance Company, an Ohio corporation ("Nationwide"), acting for itself and its wholly-owned subsidiary Allied Property & Casualty Insurance Company ("Allied") (referred to collectively as "Nationwide/Allied"), and the Attorneys General of Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Connecticut, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Washington, and the District of Columbia (referred to collectively as the "Attorneys General").2 PARTIES 1. The Attorneys General have defined jurisdiction under the laws, or assert jurisdiction under the common law, of their respective States for the enforcement of state laws and regulations, which may include state Consumer Protection Acts and state Personal Information Protection Acts. 1 This Assurance of Voluntary Compliance shall, for all necessary purposes, also be considered an Assurance of Discontinuance. 2 For simplicity purposes, the entire group will be referred to as the "Attorneys General," or individually as "Attorney General." Such designations, however, as they pertain to Hawaii shall mean the State of Hawaii, including the Executive Director of the State of Hawaii, Office of Consumer Protection and as they pertain to Connecticut, shall include the Commissioner of Consumer Protection. 2. Nationwide Mutual Insurance Company is an Ohio corporation with its principal place of business at One Nationwide Plaza, Columbus, OH 43215. Nationwide is a property and casualty insurer doing business throughout the United States, including in the States. -

Petition for Review

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT _________________________________________________ STATES OF NEW YORK, CALIFORNIA, ILLINOIS, MAINE, MINNESOTA, NEVADA, NEW MEXICO, OREGON, VERMONT, WASHINGTON, THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS, DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, AND THE CITY OF NEW YORK, Docket No. Petitioners, v. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY and JENNIFER GRANHOLM, Secretary, U.S. Department of Energy, Respondents. _________________________________________________ PETITION FOR REVIEW Pursuant to Section 336(b)(1) of the Energy Policy and Conservation Act, 42 U.S.C. § 6306(b)(1), Section 10 of the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. § 702, and Rule 15 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, the States of New York, California, Illinois, Maine, Minnesota, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Vermont, Washington, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the District of District of Columbia and the City of New York, hereby petition this Court for review of two related final actions taken by respondents, published at 86 Fed. Reg. 3873 (January 15, 2021), entitled “Energy Conservation Program for Appliance Standards: Energy Conservation Standards for Residential Furnaces and Commercial Water Heaters; Withdrawal,” and 86 Fed. Reg. 4776 (January 15, 2021), entitled “Energy Conservation Program for Appliance Standards: Energy Conservation Standards for Residential Furnaces and Commercial Water Heaters”. 1 Copies of the final rules are attached hereto. Petitioners seek a determination by the Court that the rules are unlawful and must be vacated. Dated: March 16, 2021 Respectfully submitted, FOR THE STATE OF NEW YORK LETITIA JAMES Attorney General MICHAEL J. MYERS Senior Counsel /s/ Lisa S. Kwong LISA S. KWONG TIMOTHY HOFFMAN Assistant Attorneys General Environmental Protection Bureau PATRICK A.