Global Health Engagement Features Joint Doctrine by Gerald V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Offensive Against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area Near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS

June 23, 2016 Offensive against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters at the western entrance to the city of Manbij (Fars, June 18, 2016). Overview 1. On May 31, 2016, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-dominated military alliance supported by the United States, initiated a campaign to liberate the northern Syrian city of Manbij from ISIS. Manbij lies west of the Euphrates, about 35 kilometers (about 22 miles) south of the Syrian-Turkish border. In the three weeks since the offensive began, the SDF forces, which number several thousand, captured the rural regions around Manbij, encircled the city and invaded it. According to reports, on June 19, 2016, an SDF force entered Manbij and occupied one of the key squares at the western entrance to the city. 2. The declared objective of the ground offensive is to occupy Manbij. However, the objective of the entire campaign may be to liberate the cities of Manbij, Jarabulus, Al-Bab and Al-Rai, which lie to the west of the Euphrates and are ISIS strongholds near the Turkish border. For ISIS, the loss of the area is liable to be a severe blow to its logistic links between the outside world and the centers of its control in eastern Syria (Al-Raqqah), Iraq (Mosul). Moreover, the loss of the region will further 112-16 112-16 2 2 weaken ISIS's standing in northern Syria and strengthen the military-political position and image of the Kurdish forces leading the anti-ISIS ground offensive. -

Civil Wars & Global Disorder

on the horizon: Dædalus Ending Civil Wars: Constraints & Possibilities edited by Karl Eikenberry & Stephen D. Krasner Francis Fukuyama, Tanisha M. Fazal, Stathis N. Kalyvas, Steven Heydemann, Chuck Call & Susanna P. Campbell, Sumit Ganguly, Clare Lockhart, Thomas Risse & Eric Stollenwerk, Tanja A. Börzel & Sonja Grimm, Seyoum Mesfi n & Abdeta Beyene, Lyse Doucet, Nancy Lindborg & Joseph Hewitt, Richard Gowan & Stephen John Stedman, and Jean-Marie Guéhenno & Global Disorder: Threats Opportunities 2017 Civil Wars Fall Dædalus Native Americans & Academia Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences edited by Ned Blackhawk, K. Tsianina Lomawaima, Bryan McKinley Jones Brayboy, Philip J. Deloria, Fall 2017 Loren Ghiglione, Douglas Medin, and Mark Trahant Anti-Corruption: Best Practices edited by Robert I. Rotberg Civil Wars & Global Disorder: Threats & Opportunities Karl Eikenberry & Stephen D. Krasner, guest editors with James D. Fearon Bruce D. Jones & Stephen John Stedman Stewart Patrick · Martha Crenshaw Paul H. Wise & Michele Barry Representing the intellectual community in its breadth Sarah Kenyon Lischer · Vanda Felbab-Brown and diversity, Dædalus explores the frontiers of Hendrik Spruyt · Stephen Biddle · William Reno knowledge and issues of public importance. Aila M. Matanock & Miguel García-Sánchez Barry R. Posen U.S. $15; www.amacad.org; @americanacad Civil War & the Current International System James D. Fearon Abstract: This essay sketches an explanation for the global spread of civil war up to the early 1990s and the partial -

WIIS DC Think Tank Gender Scorecard – DATASET 2018 Index/Appendix: American Enterprise Institute (AEI) Foreign and Defense

• Nonresident Fellow, Rafik Hariri Center for the WIIS DC Think Tank Gender Scorecard – Middle East: Mona Alami (F) DATASET 2018 Index/Appendix: • Nonresident Senior Fellow, Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center: Laura Albornoz Pollmann (F) • Nonresident Senior Fellow, Rafik Hariri Center for American Enterprise Institute (AEI) the Middle East: Ali Alfoneh (M) Foreign and Defense Policy Scholars in AEI: • Associate Director for Programs, Rafik Hariri Center • Visiting Scholar: Samuel J. Abrams (M) for the Middle East: Stefanie Hausheer Ali (F) • Wilson H. Taylor Scholar in Health Care and • Nonresident Senior Fellow, Cyber Statecraft Retirement Policy: Joseph Antos (M) Initiative: Dmitri Alperovitch (M) • Resident Scholar and Director of Russian Studies: • Nonresident Fellow, Rafik Hariri Center: Dr. Hussein Leon Aron (M) Amach (M) • Visiting Fellow: John P. Bailey (M) • Nonresident Fellow, Brent Scowcroft Center on • Resident Scholar: Claude Barfield (M) International Security: Dave Anthony (M) • Resident Fellow: Michael Barone (M) • Nonresident Senior Fellow, Global Energy Center: • Visiting Scholar: Robert J. Barro (M) Ragnheiður Elín Árnadóttir (F) • Visiting Scholar: Roger Bate (M) • Visiting Fellow, Brent Scowcroft Center on • Visiting Scholar: Eric J. Belasco (M) International Security/RUSI: Lisa Aronsson (F) • Resident Scholar: Andrew G. Biggs (M) • Executive Vice Chair, Atlantic Council Board of • Visiting Fellow: Edward Blum (M) Directors and International Advisory Board; Chair, • Director of Asian Studies and Resident Fellow: Dan Atlantic Council Business Development and New Blumenthal (M) Ventures Committee; Chairman Emerita, TotalBank • Senior Fellow: Karlyn Bowman (F) (no photo) • Resident Fellow: Alex Brill (M) • Atlantic Council Representative; Director, Atlantic • President; Beth and Ravenel Curry Scholar in Free Council IN TURKEY and Istanbul Summit: Defne Enterprise: Arthur C. -

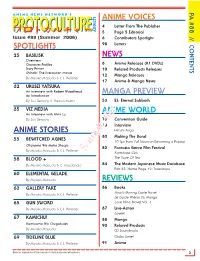

Protoculture Addicts

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan

Fall 08 September 2012 Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians From US Drone Practices in Pakistan International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic Stanford Law School Global Justice Clinic http://livingunderdrones.org/ NYU School of Law Cover Photo: Roof of the home of Faheem Qureshi, a then 14-year old victim of a January 23, 2009 drone strike (the first during President Obama’s administration), in Zeraki, North Waziristan, Pakistan. Photo supplied by Faheem Qureshi to our research team. Suggested Citation: INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION CLINIC (STANFORD LAW SCHOOL) AND GLOBAL JUSTICE CLINIC (NYU SCHOOL OF LAW), LIVING UNDER DRONES: DEATH, INJURY, AND TRAUMA TO CIVILIANS FROM US DRONE PRACTICES IN PAKISTAN (September, 2012) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I ABOUT THE AUTHORS III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS V INTRODUCTION 1 METHODOLOGY 2 CHALLENGES 4 CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 7 DRONES: AN OVERVIEW 8 DRONES AND TARGETED KILLING AS A RESPONSE TO 9/11 10 PRESIDENT OBAMA’S ESCALATION OF THE DRONE PROGRAM 12 “PERSONALITY STRIKES” AND SO-CALLED “SIGNATURE STRIKES” 12 WHO MAKES THE CALL? 13 PAKISTAN’S DIVIDED ROLE 15 CONFLICT, ARMED NON-STATE GROUPS, AND MILITARY FORCES IN NORTHWEST PAKISTAN 17 UNDERSTANDING THE TARGET: FATA IN CONTEXT 20 PASHTUN CULTURE AND SOCIAL NORMS 22 GOVERNANCE 23 ECONOMY AND HOUSEHOLDS 25 ACCESSING FATA 26 CHAPTER 2: NUMBERS 29 TERMINOLOGY 30 UNDERREPORTING OF CIVILIAN CASUALTIES BY US GOVERNMENT SOURCES 32 CONFLICTING MEDIA REPORTS 35 OTHER CONSIDERATIONS -

HD in 2020: Peacemaking in Perspective → Page 10 About HD → Page 6 HD Governance: the Board → Page 30

June 2021 EN About HD in 2020: HD governance: HD → page 6 Peacemaking in perspective → page 10 The Board → page 30 Annual Report 2020 mediation for peace www.hdcentre.org Trusted. Neutral. Independent. Connected. Effective. The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) mediates between governments, non-state armed groups and opposition parties to reduce conflict, limit the human suffering caused by war and develop opportunities for peaceful settlements. As a non-profit based in Switzerland, HD helps to build the path to stability and development for people, communities and countries through more than 50 peacemaking projects around the world. → Table of contents HD in 2020: Peacemaking in perspective → page 10 COVID in conflict zones → page 12 Social media and cyberspace → page 12 Supporting peace and inclusion → page 14 Middle East and North Africa → page 18 Francophone Africa → page 20 The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) is a private diplomacy organisation founded on the principles of humanity, Anglophone and Lusophone Africa → page 22 impartiality, neutrality and independence. Its mission is to help prevent, mitigate and resolve armed conflict through dialogue and mediation. Eurasia → page 24 Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) Asia → page 26 114 rue de Lausanne, 1202 – Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 (0)22 908 11 30 Email: [email protected] Latin America → page 28 Website: www.hdcentre.org Follow HD on Twitter and Linkedin: https://twitter.com/hdcentre https://www.linkedin.com/company/centreforhumanitariandialogue Design and layout: Hafenkrone © 2021 – Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue About HD governance: Investing Reproduction of all or part of this publication may be authorised only with written consent or acknowledgement of the source. -

The Biden Administration and the Middle East: Policy Recommendations for a Sustainable Way Forward

THE BIDEN ADMINISTRATION AND THE MIDDLE EAST: POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR A SUSTAINABLE WAY FORWARD THE MIDDLE EAST INSTITUTE MARCH 2021 WWW.MEI.EDU 2 The Biden Administration and the Middle East: Policy Recommendations for a Sustainable Way Forward The Middle East Institute March 2021 3 CONTENTS FOREWORD Iraq 21 Strategic Considerations for Middle East Policy 6 Randa Slim, Senior Fellow and Director of Conflict Paul Salem, President Resolution and Track II Dialogues Program Gerald Feierstein, Senior Vice President Ross Harrison, Senior Fellow and Director of Research Israel 23 Eran Etzion, Non-Resident Scholar POLICY BRIEFS Jordan 26 Dima Toukan, Non-Resident Scholar Countries/Regions Paul Salem, President US General Middle East Interests & Policy Priorities 12 Paul Salem, President Lebanon 28 Christophe Abi-Nassif, Director of Lebanon Program Afghanistan 14 Marvin G. Weinbaum, Director of Afghanistan and Libya 30 Pakistan Program Jonathan M. Winer, Non-Resident Scholar Algeria 15 Morocco 32 Robert Ford, Senior Fellow William Lawrence, Contributor Egypt 16 Pakistan 34 Mirette F. Mabrouk, Senior Fellow and Director of Marvin G. Weinbaum, Director of Afghanistan and Egypt Program Pakistan Program Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) 18 Palestine & the Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process 35 Gerald Feierstein, Senior Vice President Nathan Stock, Non-Resident Scholar Khaled Elgindy, Senior Fellow and Director of Program Horn of Africa & Red Sea Basin 19 on Palestine and Palestinian-Israeli Affairs David Shinn, Non-Resident Scholar Saudi Arabia 37 Iran -

The Terrorism Trap: the Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2019 The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror John Akins University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Akins, John, "The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5624 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by John Akins entitled "The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Political Science. Krista Wiegand, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Brandon Prins, Gary Uzonyi, Candace White Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America’s War on Terror A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville John Harrison Akins August 2019 Copyright © 2019 by John Harrison Akins All rights reserved. -

Ki No Tsurayuki a Poszukiwanie Tożsamości Kulturowej W Literaturze Japońskiej X Wieku

Title: Ki no Tsurayuki a poszukiwanie tożsamości kulturowej w literaturze japońskiej X wieku Author: Krzysztof Olszewski Citation style: Olszewski Krzysztof. (2003). Ki no Tsurayuki a poszukiwanie tożsamości kulturowej w literaturze japońskiej X wieku. Kraków : Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego Ki no Tsurayuki a poszukiwanie tożsamości kulturowej w literaturze japońskiej X wieku Literatura, język i kultura Japonii Krzysztof Olszewski Ki no Tsurayuki a poszukiwanie tożsamości kulturowej w literaturze japońskiej X wieku WYDAWNICTWO UNIWERSYTETU JAGIELLOŃSKIEGO Seria: Literatura, język i kultura Japonii Publikacja finansowana przez Komitet Badań Naukowych oraz ze środków Instytutu Filologii Orientalnej oraz Wydziału Filologicznego Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego RECENZENCI Romuald Huszcza Alfred M. Majewicz PROJEKT OKŁADKI Marcin Bruchnalski REDAKTOR Jerzy Hrycyk KOREKTOR Krystyna Dulińska © Copyright by Krzysztof Olszewski & Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego Wydanie I, Kraków 2003 All rights reserved ISBN 83-233-1660-0 Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego Dystrybucja: ul. Bydgoska 19 C, 30-056 Kraków Tel. (012) 638-77-83, 636-80-00 w. 2022, 2023, fax (012) 430-19-95 Tel. kom. 0604-414-568, e-mail: wydaw@if. uj. edu.pl http: //www.wuj. pl Konto: BPH PBK SA IV/O Kraków nr 10601389-320000478769 A MOTTO Księżyc, co mieszka w wodzie, Nabieram w dłonie Odbicie jego To jest, to niknie znowu - Świat, w którym przyszło mi żyć. Ki no Tsurayuki, testament poetycki' W świątyni w Iwai Będę się modlił za Ciebie I czekał całe wieki. Choć -

Trump's Generals

STRATEGIC STUDIES QUARTERLY - PERSPECTIVE Trump’s Generals: A Natural Experiment in Civil-Military Relations JAMES JOYNER Abstract President Donald Trump’s filling of numerous top policy positions with active and retired officers he called “my generals” generated fears of mili- tarization of foreign policy, loss of civilian control of the military, and politicization of the military—yet also hope that they might restrain his worst impulses. Because the generals were all gone by the halfway mark of his administration, we have a natural experiment that allows us to com- pare a Trump presidency with and without retired generals serving as “adults in the room.” None of the dire predictions turned out to be quite true. While Trump repeatedly flirted with civil- military crises, they were not significantly amplified or deterred by the presence of retired generals in key roles. Further, the pattern continued in the second half of the ad- ministration when “true” civilians filled these billets. Whether longer-term damage was done, however, remains unresolved. ***** he presidency of Donald Trump served as a natural experiment, testing many of the long- debated precepts of the civil-military relations (CMR) literature. His postelection interviewing of Tmore than a half dozen recently retired four- star officers for senior posts in his administration unleashed a torrent of columns pointing to the dangers of further militarization of US foreign policy and damage to the military as a nonpartisan institution. At the same time, many argued that these men were uniquely qualified to rein in Trump’s worst pro- clivities. With Trump’s tenure over, we can begin to evaluate these claims. -

Air Force World by Autumn A

Air Force World By Autumn A. Arnett, Associate Editor House Passes Fiscal 2015 Defense Spending Bill Langley-Eustis, Va. Carlisle has served as commander of The House approved HR 4870, its version of the Fiscal Pacifi c Air Forces at JB Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii, since 2015 defense spending bill, June 20, providing $491 bil- August 2012. lion in discretionary funding and $79.4 billion for overseas Obama also on July 15 nominated Lt. Gen. Lori J. Robinson contingency operations, including the war in Afghanistan. for a fourth star and for assignment as commander of Pacifi c Air Among the Air Force-related amendments adopted on Forces. She has been ACC vice commander since May 2013. the House fl oor is one introduced by Rep. Candice Miller (R-Mich.) that blocked the Air Force from using Fiscal 2015 funds to divest, retire, transfer, or place into storage any A-10 aircraft or to dissolve any A-10 units. An amendment brought forth by Rep. Jon Runyan (R-N.J.) that prohibits KC-10 retirements in Fiscal 2015 also passed. The House in May passed its version of the Fiscal 2015 screenshot defense authorization bill, which also prevents divestiture of the A-10 fl eet. Medal of Honor Awarded to Marine President Barack Obama awarded the Medal of Honor to retired Marine Corps Cpl. William “Kyle” Carpenter, 24, on June 19 for his conspicuous gallantry during a 2010 battle in Afghanistan where he was seriously injured. “Anybody who has had a chance to get to know this young man knows you’re not going to get a better example of what you want in an American or a marine,” said Obama during the White House ceremony. -

Enclosed Is the Header; the Next Three Posts Contain the 517K Flat-Text of the "1984" Polemic

Enclosed is the header; the next three posts contain the 517K flat-text of the "1984" polemic. For hardcore details on ECHELON, see Part 1 from 'Wild Conspiracy Theory' through the end of Part 1. ---guy ****************************************************************************** An Indictment of the U.S. Government and U.S. Politics Cryptography Manifesto ---------------------- By [email protected] 7/4/97-M version "The law does not allow me to testify on any aspect of the National Security Agency, even to the Senate Intelligence Committee" ---General Allen, Director of the NSA, 1975 "You bastards!" ---guy ****************************************************************************** This is about much more than just cryptography. It is also about everyone in the U.S.A. being fingerprinted for a defacto national ID card, about massive illegal domestic spying by the NSA, about the Military being in control of key politicians, about always being in a state of war, and about cybernetic control of society. ****************************************************************************** Part 1: Massive Domestic Spying via NSA ECHELON ---- - ------- -------- ------ --- --- ------- o The NSA Admits o Secret Court o Wild Conspiracy Theory o Over the Top o BAM-BAM-BAM o Australian ECHELON Spotted o New Zealand: Unhappy Campers Part 2: On Monitoring and Being Monitored ---- - -- ---------- --- ----- --------- o On Monitoring - Driver's Seat - Five Months Statistics - The FBI Investigations - I Can See What You Are Thinking - Why I Monitor o On Being