100 Years of Bird Behaviour Studies Angela Turner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luscinia Luscinia)

Ornis Hungarica 2018. 26(1): 149–170. DOI: 10.1515/orhu-2018-0010 Exploratory analyses of migration timing and morphometrics of the Thrush Nightingale (Luscinia luscinia) Tibor CSÖRGO˝ 1 , Péter FEHÉRVÁRI2, Zsolt KARCZA3, Péter ÓCSAI4 & Andrea HARNOS2* Received: April 20, 2018 – Revised: May 10, 2018 – Accepted: May 20, 2018 Tibor Csörgo,˝ Péter Fehérvári, Zsolt Karcza, Péter Ócsai & Andrea Harnos 2018. Exploratory analyses of migration timing and morphometrics of the Thrush Nightingale (Luscinia luscinia). – Ornis Hungarica 26(1): 149–170. DOI: 10.1515/orhu-2018-0010 Abstract Ornithological studies often rely on long-term bird ringing data sets as sources of information. However, basic descriptive statistics of raw data are rarely provided. In order to fill this gap, here we present the seventh item of a series of exploratory analyses of migration timing and body size measurements of the most frequent Passerine species at a ringing station located in Central Hungary (1984–2017). First, we give a concise description of foreign ring recoveries of the Thrush Nightingale in relation to Hungary. We then shift focus to data of 1138 ringed and 547 recaptured individuals with 1557 recaptures (several years recaptures in 76 individuals) derived from the ringing station, where birds have been trapped, handled and ringed with standardized methodology since 1984. Timing is described through annual and daily capture and recapture frequencies and their descriptive statistics. We show annual mean arrival dates within the study period and present the cumulative distributions of first captures with stopover durations. We present the distributions of wing, third primary, tail length and body mass, and the annual means of these variables. -

On the Status and Distribution of Thrush Nightingale Luscinia Luscinia and Common Nightingale L

Sandgrouse31-090402:Sandgrouse 4/2/2009 11:21 AM Page 18 On the status and distribution of Thrush Nightingale Luscinia luscinia and Common Nightingale L. megarhynchos in Armenia VASIL ANANIAN INTRODUCTION In the key references on the avifauna of the Western Palearctic and former Soviet Union, the breeding distributions of Common Luscinia megarhynchos and Thrush Nightingales L. luscinia in the Transcaucasus (Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan) are presented inconsistently, especially for the latter species. These sources disagree on the status of Thrush Nightingale in the area, thus Vaurie (1959), Cramp (1988) and Snow & Perrins (1998) considered it breeding in the Transcaucasus, while Dementiev & Gladkov (1954), Sibley & Monroe (1990) and Stepanyan (2003) do not. Its distribu- tion in del Hoyo et al (2005) is mapped according to the latter view, but they note the species’ presence in Armenia during the breeding season. Several other publications Plate 1. Common Nightingale Luscinia megarhynchos performing full territorial song, Vorotan river gorge, c15 consider that the southern limit of Thrush km SSW of Goris town, Syunik province, Armenia, 12 May Nightingale’s Caucasian breeding range is 2005. © Vasil Ananian in the northern foothills of the Greater Caucasus mountains (Russian Federation), while the Transcaucasus is inhabited solely by Common Nightingale (Gladkov et al 1964, Flint et al 1967, Ivanov & Stegmann 1978, Vtorov & Drozdov 1980). Thrush Nightingale in Azerbaijan was classified as ‘accidental’ by Patrikeev (2004). The author accepted that the species had possibly nested in the past and referred to old summer records by GI Radde from the Karayasi forest in the Kura–Aras (Arax) lowlands, but Patrikeev found only Common Nightingale there in the late 1980s. -

![The Song Structure of the Siberian Blue Robin Luscinia [Larvivora] Cyane and a Comparison with Related Species](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7826/the-song-structure-of-the-siberian-blue-robin-luscinia-larvivora-cyane-and-a-comparison-with-related-species-897826.webp)

The Song Structure of the Siberian Blue Robin Luscinia [Larvivora] Cyane and a Comparison with Related Species

Ornithol Sci 16: 71 – 77 (2017) ORIGINAL ARTICLE The song structure of the Siberian Blue Robin Luscinia [Larvivora] cyane and a comparison with related species Vladimir IVANITSKII1,#, Alexandra IVLIEVA2, Sergey GASHKOV3 and Irina MAROVA1 1 Lomonosov Moscow State University, Biology, 119899 Moscow Leninskie Gory, Moscow, Moscow 119899, Russian Federation 2 M.F. Vladimirskii Moscow Regional Research Clinical Institute, Moscow, Moscow, Russian Federation 3 Tomsk State University-Zoology Museum, Tomsk, Tomsk, Russian Federation ORNITHOLOGICAL Abstract We studied the song syntax of the Siberian Blue Robin Luscinia cyane, a small insectivorous passerine of the taiga forests of Siberia and the Far East. Males SCIENCE have repertoires of 7 to 14 (mean 10.9±2.3) song types. A single song typically con- © The Ornithological Society sists of a short trill comprised of from three to six identical syllables, each of two to of Japan 2017 three notes; sometimes the trill is preceded by a short single note. The most complex songs contain as many as five or six different trills and single notes. The song of the Siberian Blue Robin most closely resembles that of the Indian Blue Robin L. brunnea. The individual repertoires of Siberian Blue Robin, Common Nightingale L. megarhynchos and Thrush Nightingale L. luscinia contain groups of mutually associ- ated song types that are sung usually one after another. The Siberian Blue Robin and the Common Nightingale perform them in a varying sequence, while Thrush Nightin- gale predominantly uses a fixed sequence of song types. The distinctions between the song syntax of Larvivora spp. and Luscinia spp. are discussed. -

Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas

sustainability Article Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas Vasilios Liordos 1,* , Jukka Jokimäki 2 , Marja-Liisa Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki 2, Evangelos Valsamidis 1 and Vasileios J. Kontsiotis 1 1 Department of Forest and Natural Environment Sciences, International Hellenic University, 66100 Drama, Greece; [email protected] (E.V.); [email protected] (V.J.K.) 2 Arctic Centre, University of Lapland, 96101 Rovaniemi, Finland; jukka.jokimaki@ulapland.fi (J.J.); marja-liisa.kaisanlahti@ulapland.fi (M.-L.K.-J.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Knowing the ecological requirements of bird species is essential for their successful con- servation. We studied the niche characteristics of birds in managed small-sized green spaces in the urban core areas of southern (Kavala, Greece) and northern Europe (Rovaniemi, Finland), during the breeding season, based on a set of 16 environmental variables and using Outlying Mean Index, a multivariate ordination technique. Overall, 26 bird species in Kavala and 15 in Rovaniemi were recorded in more than 5% of the green spaces and were used in detailed analyses. In both areas, bird species occupied different niches of varying marginality and breadth, indicating varying responses to urban environmental conditions. Birds showed high specialization in niche position, with 12 species in Kavala (46.2%) and six species in Rovaniemi (40.0%) having marginal niches. Niche breadth was narrower in Rovaniemi than in Kavala. Species in both communities were more strongly associated either with large green spaces located further away from the city center and having a high vegetation cover (urban adapters; e.g., Common Chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs), European Greenfinch (Chloris Citation: Liordos, V.; Jokimäki, J.; chloris Cyanistes caeruleus Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki, M.-L.; ), Eurasian Blue Tit ( )) or with green spaces located closer to the city center Valsamidis, E.; Kontsiotis, V.J. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 74/Thursday, April 16, 2020/Notices

21262 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 74 / Thursday, April 16, 2020 / Notices acquisition were not included in the 5275 Leesburg Pike, Falls Church, VA Comment (1): We received one calculation for TDC, the TDC limit would not 22041–3803; (703) 358–2376. comment from the Western Energy have exceeded amongst other items. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Alliance, which requested that we Contact: Robert E. Mulderig, Deputy include European starling (Sturnus Assistant Secretary, Office of Public Housing What is the purpose of this notice? vulgaris) and house sparrow (Passer Investments, Office of Public and Indian Housing, Department of Housing and Urban The purpose of this notice is to domesticus) on the list of bird species Development, 451 Seventh Street SW, Room provide the public an updated list of not protected by the MBTA. 4130, Washington, DC 20410, telephone (202) ‘‘all nonnative, human-introduced bird Response: The draft list of nonnative, 402–4780. species to which the Migratory Bird human-introduced species was [FR Doc. 2020–08052 Filed 4–15–20; 8:45 am]‘ Treaty Act (16 U.S.C. 703 et seq.) does restricted to species belonging to biological families of migratory birds BILLING CODE 4210–67–P not apply,’’ as described in the MBTRA of 2004 (Division E, Title I, Sec. 143 of covered under any of the migratory bird the Consolidated Appropriations Act, treaties with Great Britain (for Canada), Mexico, Russia, or Japan. We excluded DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 2005; Pub. L. 108–447). The MBTRA states that ‘‘[a]s necessary, the Secretary species not occurring in biological Fish and Wildlife Service may update and publish the list of families included in the treaties from species exempted from protection of the the draft list. -

Ringing and Observation of Migrants at Ngulia Lodge, Tsavo West National Park, Kenya, 2013–2015

Scopus 36(2): 17–25, July 2016 Ringing and observation of migrants at Ngulia Lodge, Tsavo West National Park, Kenya, 2013–2015 David Pearson Summary The review of migrant bird ringing at Ngulia Lodge by Pearson et al. (2014) is updated. During late autumn sessions in 2013, 2014 and 2015 a further 35 000 Palaearctic birds were trapped. Species ringing totals for the three years are tabulated, together with overall ringing totals since the onset of this project in 1969. Twenty long distance ringing recoveries reported since the 2014 review are listed, and a breakdown is given by country of recovery numbers since the start of the project. Between 25 November and 13 December 2013 regular persistent night mists ac- counted for a successful session with 21 052 migrants ringed. Marsh Warbler Acro- cephalus palustris formed 49% of this catch. A Wood Warbler Phylloscopus sibilatrix was the first caught here for 20 years. A Thrush NightingaleLuscinia luscinia, a Marsh Warbler and a Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica were controlled bearing foreign rings. In 2014, a session between 16 November and 2 December produced good species variety, but night mists were confined to the first week. Thrush Nightingale was the dominant species in a modest Palaearctic catch of 7051. Marsh Warbler numbers were unusually low, and one regular species, Basra Reed Warbler Acrocephalus griseldis, was almost absent. Heavy showers brought well over 1000 Eurasian Rollers Coracias garrulus and a gathering of 1500 Amur Falcons Falco amurensis to the lodge on the afternoon of 1 December. In 2015, a late session with nine misty nights between 6 and 20 December resulted in 7638 migrants ringed, with Marsh Warbler by far the dominant species. -

Version 2014-04-28 Attached Is the Dynamic1 List of Migratory Landbird

African-Eurasian Migratory Landbirds Action Plan Annex 3: Species Lists Version 2014-04-28 Attached is the dynamic1 list of migratory landbird species that occur within the African Eurasian region according to the following definition: 1. Migratory is defined as those species recorded within the IUCN Species Information Service (SIS) and BirdLife World Bird Database (WBDB) as ‘Full Migrant’, i.e. species which have a substantial (>50%) proportion of the global population which migrates: - with the addition of Great Bustard Otis tarda which is listed on CMS Appendix I and is probably erroneously recorded as an altitudinal migrant within SIS and the WBDB - with the omission of all single-country endemic migrants, in order to conform with the CMS definition of migratory which requires a species to ‘cross one or more national jurisdictional boundaries,’; in reality this has meant the removal of only one species, Madagascar Blue-pigeon Alectroenas madagascariensis. However, it should be noted that removing single-country endemics is not strictly analogous with omitting species that do not cross political borders. It is quite possible for a migratory species whose range extends across multiple countries to contain no populations that actually cross national boundaries as part of their regular migration. 2. African-Eurasian is defined as Africa, Europe (including all of the Russian Federation and excluding Greenland), the Middle East, Central Asia, Afghanistan, and the Indian sub-continent. 3. Landbird is defined as those species not recorded in SIS and the WBDB as being seabirds, raptors or waterbirds, except for the following waterbird species that are recorded as not utilising freshwater habitats: Geronticus eremita, Geronticus calvus, Burhinus oedicnemus, Cursorius cursor and Tryngites subruficollis. -

Title: Dawn Singing of the Brownish-Flanked Bush Warbler Influences Dawn Chorusing in a Bird Community

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by E-space: Manchester Metropolitan University's Research Repository Title: Dawn Singing of the Brownish-Flanked Bush Warbler Influences Dawn Chorusing in a Bird Community Short running title: interspecific influences dawn singing Authors: Canwei Xia*, Huw Lloyd†, Jie Shi*, Chentao Wei* & Yanyun Zhang* Author's institutional affiliations: * Ministry of Education Key Laboratory for Biodiversity and Ecological Engineering, College of Life Sciences, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China † Division of Biology and Conservation Ecology, School of Science and the Environment, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, UK Correspondence: Yanyun Zhang, Ministry of Education Key Laboratory for Biodiversity and Ecological Engineering, College of Life Sciences, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China. E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgements: We thank Prof. Anders Pape Møller and Dr. Lu Dong for helpful comments. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31601868) and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No. 5173030). All aspects of this study were approved by the National Bird-banding Center of China (NBCC) under license number H20110042 and the local administrator of the Dongzhai National Nature Reserve under permit number 2011002. Authorship: Canwei Xia and Yanyun Zhang conceived and designed the experiments. Chentao Wei collected the data. Jie Shi analyzed the data. Canwei Xia, Huw Lloyd and Yanyun Zhang wrote the manuscript. Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest to this work. Abstract: Despite numerous studies on the function of the avian dawn chorus, few studies have examined whether dawn singing may influence the singing of other species. -

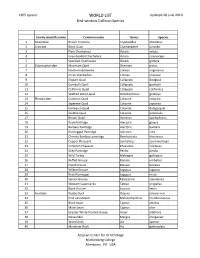

WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-Window Collision Species

1305 species WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-window Collision Species Family scientific name Common name Genus Species 1 Tinamidae Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus 2 Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor 3 Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula 4 Grey-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps 5 Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 6 Odontophoridae Mountain Quail Oreortyx pictus 7 Northern Bobwhite Colinus virginianus 8 Crested Bobwhite Colinus cristatus 9 Elegant Quail Callipepla douglasii 10 Gambel's Quail Callipepla gambelii 11 California Quail Callipepla californica 12 Spotted Wood-quail Odontophorus guttatus 13 Phasianidae Common Quail Coturnix coturnix 14 Japanese Quail Coturnix japonica 15 Harlequin Quail Coturnix delegorguei 16 Stubble Quail Coturnix pectoralis 17 Brown Quail Synoicus ypsilophorus 18 Rock Partridge Alectoris graeca 19 Barbary Partridge Alectoris barbara 20 Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa 21 Chinese Bamboo-partridge Bambusicola thoracicus 22 Copper Pheasant Syrmaticus soemmerringii 23 Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus 24 Grey Partridge Perdix perdix 25 Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo 26 Ruffed Grouse Bonasa umbellus 27 Hazel Grouse Bonasa bonasia 28 Willow Grouse Lagopus lagopus 29 Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta 30 Spruce Grouse Falcipennis canadensis 31 Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus 32 Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix 33 Anatidae Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 34 Pink-eared Duck Malacorhynchus membranaceus 35 Black Swan Cygnus atratus 36 Mute Swan Cygnus olor 37 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons 38 -

Madrid Hot Birding, Closer Than Expected

Birding 04-06 Spain2 2/9/06 1:50 PM Page 38 BIRDING IN THE OLD WORLD Madrid Hot Birding, Closer Than Expected adrid is Spain’s capital, and it is also a capital place to find birds. Spanish and British birders certainly know M this, but relatively few American birders travel to Spain Howard Youth for birds. Fewer still linger in Madrid to sample its avian delights. Yet 4514 Gretna Street 1 at only seven hours’ direct flight from Newark or 8 ⁄2 from Miami, Bethesda, Maryland 20814 [email protected] Madrid is not that far off. Friendly people, great food, interesting mu- seums, easy city transit, and great roads make central Spain a great va- cation destination. For a birder, it can border on paradise. Spain holds Europe’s largest populations of many species, including Spanish Imperial Eagle (Aquila heliaca), Great (Otis tarda) and Little (Tetrax tetrax) Bustards, Eurasian Black Vulture (Aegypius monachus), Purple Swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio), and Black Wheatear (Oenanthe leucura). All of these can be seen within Madrid Province, the fo- cus of this article, all within an hour’s drive of downtown. The area holds birding interest year-round. Many of northern Europe’s birds winter in Spain, including Common Cranes (which pass through Madrid in migration), an increasing number of over-wintering European White Storks (Ciconia ciconia), and a wide variety of wa- terfowl. Spring comes early: Barn Swallows appear by February, and many Africa-wintering water birds arrive en masse in March. Other migrants, such as European Bee-eater (Merops apiaster), Common Nightingale (Luscinia megarhynchos), and Golden Oriole (Oriolus ori- olous), however, rarely arrive before April. -

The First Record of a Female Hybrid Between the Common Nightingale

J Ornithol (2011) 152:1063–1068 DOI 10.1007/s10336-011-0700-7 SHORT NOTE The first record of a female hybrid between the Common Nightingale (Luscinia megarhynchos) and the Thrush Nightingale (Luscinia luscinia) in nature Radka Reifova´ • Pavel Kverek • Jirˇ´ı Reif Received: 12 September 2010 / Revised: 11 March 2011 / Accepted: 27 April 2011 / Published online: 17 May 2011 Ó Dt. Ornithologen-Gesellschaft e.V. 2011 Abstract Understanding the mechanisms causing repro- experimental work in captivity suggests that hybrid female ductive isolation between incipient species can give sterility plays an important role in reproductive isolation in important insights into the process of species origin. Here, nightingales. Unexpectedly, the hybrid female had highly we describe a record of a hybrid female between two developed fat reserves and was in the process of moulting, closely related bird species, the Common Nightingale which in nightingales normally occurs approximately (Luscinia megarhynchos) and the Thrush Nightingale 1 month later. This unusual moult pattern could contribute (L. luscinia). These species are separated by incomplete to lower fitness of hybrid females and thus to speciation in prezygotic isolation, and the occurrence of fertile hybrid nightingales. males in nature has been documented before. Our record represents the first genetically confirmed evidence of the Keywords Luscinia megarhynchos Á Luscinia luscinia Á occurrence of hybrid females between these two species in Hybridization Á Hybrid sterility Á Bird moult nature. Although the hybrid female was captured in the peak of the breeding season in suitable habitat, it did not Zusammenfassung Die Mechanismen zu verstehen, die show any sign of reproductive activity, suggesting that it zu reproduktiver Isolation werdender Arten fu¨hren, kann was sterile. -

First-Year Common Nightingales (Luscinia

Ethology First-Year Common Nightingales (Luscinia megarhynchos) Have Smaller Song-Type Repertoire Sizes Than Older Males Sarah Kiefer*, Anne Spiess* , Silke Kipper*, Roger Mundry*à, Christina Sommer*, Henrike Hultsch* & Dietmar Todt* * Institute of Biology, Behavioural Biology, Freie Universita¨ t, Berlin, Germany Department of Life Sciences, Anglia Polytechnic University, Cambridge, UK à Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany Correspondence Abstract S. Kiefer, Institute of Biology, Verhaltensbiologie, Freie Universita¨ t, Berlin, Based on the assumptions that birdsong indicates male quality and that Grunewaldstr. 34, 12165 Berlin, Germany. quality is related to age, one might expect older birds to signal their age. E-mail: [email protected] That is, in addition to actual body condition, at least some song features should vary with age, presumably towards more complexity. We investi- Received: January 20, 2006 gated this issue by comparing repertoire sizes of free-ranging common Initial acceptance: March 15, 2006 nightingale males in their first breeding season with those of older Final acceptance: June 20, 2006 (K. Riebel) males. Nightingales are a good model species as they are open-ended doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2006.01283.x learners, where song acquisition is not confined to an early sensitive period of learning. Moreover, nightingales develop an extraordinarily large song-type repertoire (approx. 180 different song types per male), and differences in repertoire size among males are pronounced. We ana- lysed repertoire characteristics of the nocturnal song of nine nightingales in their first breeding season and compared them with the songs of nine older males. The repertoire size of older males was on average 53% lar- ger than that of yearlings.