Jammu—The City of Temples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YES BANK LTD.Pdf

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE ANDAMAN Ground floor & First Arpan AND floor, Survey No Basak - NICOBAR 104/1/2, Junglighat, 098301299 ISLAND ANDAMAN Port Blair Port Blair - 744103. PORT BLAIR YESB0000448 04 Ground Floor, 13-3- Ravindra 92/A1 Tilak Road Maley- ANDHRA Tirupati, Andhra 918374297 PRADESH CHITTOOR TIRUPATI, AP Pradesh 517501 TIRUPATI YESB0000485 779 Ground Floor, Satya Akarsha, T. S. No. 2/5, Door no. 5-87-32, Lakshmipuram Main Road, Guntur, Andhra ANDHRA Pradesh. PIN – 996691199 PRADESH GUNTUR Guntur 522007 GUNTUR YESB0000587 9 Ravindra 1ST FLOOR, 5 4 736, Kumar NAMPALLY STATION Makey- ANDHRA ROAD,ABIDS, HYDERABA 837429777 PRADESH HYDERABAD ABIDS HYDERABAD, D YESB0000424 9 MR. PLOT NO.18 SRI SHANKER KRUPA MARKET CHANDRA AGRASEN COOP MALAKPET REDDY - ANDHRA URBAN BANK HYDERABAD - HYDERABA 64596229/2 PRADESH HYDERABAD MALAKPET 500036 D YESB0ACUB02 4550347 21-1-761,PATEL MRS. AGRASEN COOP MARKET RENU ANDHRA URBAN BANK HYDERABAD - HYDERABA KEDIA - PRADESH HYDERABAD RIKABGUNJ 500002 D YESB0ACUB03 24563981 2-4-78/1/A GROUND FLOOR ARORA MR. AGRASEN COOP TOWERS M G ROAD GOPAL ANDHRA URBAN BANK SECUNDERABAD - HYDERABA BIRLA - PRADESH HYDERABAD SECUNDRABAD 500003 D YESB0ACUB04 64547070 MR. 15-2-391/392/1 ANAND AGRASEN COOP SIDDIAMBER AGARWAL - ANDHRA URBAN BANK BAZAR,HYDERABAD - HYDERABA 24736229/2 PRADESH HYDERABAD SIDDIAMBER 500012 D YESB0ACUB01 4650290 AP RAJA MAHESHWARI 7 1 70 DHARAM ANDHRA BANK KARAN ROAD HYDERABA 40 PRADESH HYDERABAD AMEERPET AMEERPET 500016 D YESB0APRAJ1 23742944 500144259 LADIES WELFARE AP RAJA CENTRE,BHEL ANDHRA MAHESHWARI TOWNSHIP,RC HYDERABA 40 PRADESH HYDERABAD BANK BHEL PURAM 502032 D YESB0APRAJ2 23026980 SHOP NO:G-1, DEV DHANUKA PRESTIGE, ROAD NO 12, BANJARA HILLS HYDERABAD ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH HYDERABA PRADESH HYDERABAD BANJARA HILLS 500034 D YESB0000250 H NO. -

Historical Places

Where to Next? Explore Jammu Kashmir And Ladakh By :- Vastav Sharma&Nikhil Padha (co-editors) Magazine Description Category : Travel Language: English Frequency: Twice in a Year Jammu Kashmir and Ladakh Unlimited is the perfect potrait of the most beautiful place of the world Jammu, Kashmir&Ladakh. It is for Travelers, Tourism Entrepreneurs, Proffessionals as well as those who dream to travel Jammu,Kashmir&Ladakh and have mid full of doubts. This is a new kind of travel publication which trying to promoting the J&K as well as Ladakh tourism industry and remove the fake potrait from the minds of people which made by media for Jammu,Kashmir&Ladakh. Jammu Kashmir and ladakh Unlimited is a masterpiece, Which is the hardwork of leading Travel writters, Travel Photographer and the team. This magazine has covered almost every tourist and pilgrimage sites of Jammu Kashmir & Ladakh ( their stories, history and facts.) Note:- This Magazine is only for knowledge based and fact based magazine which work as a tourist guide. For any kind of credits which we didn’t mentioned can claim for credits through the editors and we will provide credits with description of the relevent material in our next magazine and edit this one too if possible on our behalf. Reviews “Kashmir is a palce where not even words, even your emotions fail to describe its scenic beauty. (Name of Magazine) is a brilliant guide for travellers and explore to know more about the crown of India.” Moohammed Hatim Sadriwala(Poet, Storyteller, Youtuber) “A great magazine with a lot of information, facts and ideas to do at these beautiful places.” Izdihar Jamil(Bestselling Author Ted Speaker) “It is lovely and I wish you the very best for the initiative” Pritika Kumar(Advocate, Author) “Reading this magazine is a peace in itself. -

Print This Article

Journal of tourism – studies and research in tourism [Issue 18] APPLICATION OF PROMOTION TOOLS IN HOSPITALITY AND TOURISM INDUSTRY AND ITS ROLE IN DEVELOPING THE JAMMU AND KASHMIR AS A TOURIST DESTINATION Zoltán BUJDOSÓ Károly Róbert University College, 3200, Hungary [email protected] Parikshat Shing MANHAS The Business School and School of Hospitality and Tourism Management University of Jammu, 18006, India [email protected] RAMJIT University of Jammu, 18006, India [email protected] Lóránt DÁVID Eszterházy Károly University College, 3300, Hungary [email protected] Alexandru NEDELEA Stefan cel Mare University of Suceava, 720229, Romania [email protected] Abstract The proposed study will mainly attempt to study the promotional tools undertaken by different hotels and tour operators, and evaluate how they have been able to develop tourism and hospitality industry in the state. A survey questionnaire was used to collect primary data. Our study revealed that the main reason of not succeeding and overcoming the problem of rebuilding the state as a tourists destination after the period of militancy and others problems mainly lies within the negligence of tourism authorities not following appropriate marketing activities ; inappropriate measures and wrong allocation of promotional funds also contribute to the problem. Key words: Promotion tools, Tourism industry, Hospitality industry, Tourism products and services, Brand image, Jammu and Kashmir. JEL Classification: M41, M31, O21 I. INTRODUCTION II. LITERATURE REVIEW Tourism industry plays a vital role both at global Promotion cannot be fully effective unless it is and individual levels. Many countries depend on coordinated together with the other three ‘P’s tourism as a main source of foreign income. -

INTERNET FACILITATION CENTRE for PMSSS, JAMMU Division (Facilitation Cum Registration Centre)

INTERNET FACILITATION CENTRE FOR PMSSS, JAMMU Division (Facilitation cum Registration Centre) S.No District School Name Nodal Officer Contact No of Connectivity Nodal Officer HSS GOVT. HR. SEC. Chander Mohan 1 Jammu 9419860196 2G SCHOOL JANDRAH Sharma 2 Jammu HS DEVIPUR Kanchan Gupta 8492004794 2G 3 Jammu HS KALEETH Subhash Chander 9419302332 2G 4 Jammu HSS KHARAH Kura Ram 9149826003 2G 5 Jammu HS CHOWADI Kamlesh Kumari 8825011938 2G 6 Jammu HS Pakhain Ishar Dass 7006337982 2G 7 Jammu HSS CHHANI HIMMAT Shanaz 9469167222 2G Chowdhary 8 Jammu HSS GANDHI NAGAR Shafqat Javed 9419117541 2G Chib 9 Jammu MS Gurha Talab Lakhbir Singh 9906358163 2G 10 Jammu HS MAWA BRAHMANA Surinder Mohan 9469172043 2G Singh 11 Jammu HS GANJANSOO Mrs Rita Gupta 9469132880 2G 12 Jammu GHS BURJ MANDIR Smt Satyadevi 9906292895 2G 13 Jammu HSS DHAKAR Sh. Ram Pal 7889344437 2G Sharma HSS GOVT CH. CL 14 Jammu MEMORIAL CHAKROHI. Bimla Devi 8803553669 2G 15 Jammu HS Kangrail Mrs Rano Devi 9858041086 2G 16 Jammu GHS DOGRA HALL Mtr.Tasleem Bano 9906292662 2G 17 Jammu HSS MUTHI Manmeet Kaur 9419253294 2G 18 Jammu HS BALIYAL Smt Namarta Devi 9858601732 2G 19 Jammu HSS CHOWKI-CHOURA Veena Kerni 9419143705 2G 20 Jammu GHS BHOUR CAMP WARD Rajni Kumari 9419173777 2G NO. HSS R.S PURA WARD 21 Jammu NO(BOYS ONLY) S Pritam Singh 9469171265 2G 22 Jammu HS JINDER MELU (RMSA) Ravinder Kour, 7889368940 2G Master 23 Jammu HSS SAI Parveen Akhtar 9419021035 2G 24 Jammu HSS KERI Smt Ravinder Kour 9419239396 2G 25 Jammu GHSS ARNIA Santosh Kumari 9419198680 2G HSS MIGRANT CAMP 26 Jammu NAGOROTA -

Hospital Master

S.No HOSPITALNAME STREET CITYDESC STATEDESC PINCODE 1 Highway Hospital Dev Ashish Jeen Hath Naka, Maarathon Circle Mumbai and Maharashtra 400601 Suburb 2 PADMAVATI MATERNITY AND 215/216- Oswal Oronote, 2nd Thane Maharashtra 401105 NURSING HOME 3 Jai Kamal Eye Hospital Opp Sandhu Colony G.T.Road, Chheharta, Amritsar Amritsar Punjab 143001 4 APOLLO SPECIALITY HOSPITAL Chennai By-Pass Road, Tiruchy TamilNadu 620010 5 Khanna Hospital C2/396,Janakpuri New Delhi Delhi 110058 6 B.M Gupta Nursing Home H-11-15 Arya Samaj Road,Uttam Nagar New Delhi Delhi 110059 Pvt.Ltd. 7 Divakar Global Hospital No. 220, Second Phase, J.P.Nagar, Bengaluru Karnataka 560078 8 Anmay Eye Hospital - Dr Off. C.G. Road , Nr. President Hotel,Opp. Mahalya Ahmedabad Gujarat 380009 Raminder Singh Building, Navrangpura 9 Tilak Hospital Near Ramlila Ground,Gurgaon Road,Pataudi,Gurgaon-Gurugram Haryana 122503 122503 10 GLOBAL 5 Health Care F-2, D-2, Sector9, Main Road, Vashi, Navi Mumbai Mumbai and Maharashtra 400703 Suburb 11 S B Eye Care Hospital Anmol Nagar, Old Tanda Road, Tanda By-Pass, Hoshiarpur Punjab 146001 Hoshiarpur 12 Dhir Eye Hospital Old Court Road Rajpura Punjab 140401 13 Bilal Hospital Icu Ryal Garden,A wing,Nr.Shimla Thane Maharashtra 401201 Park,Kausa,Mumbra,Thane 14 Renuka Eye Institute 25/3,Jessre road,Dakbanglow Kolkata West Bengal 700127 More,Rathala,Barsat,Kolkatta 15 Pardi Hospital Nh No-8, Killa Pardi, Opp. Renbasera HotelPardi Valsad Gujarat 396001 16 Jagat Hospital Raibaraily Road, Naka Chungi, Faizabad Faizabad Uttar Pradesh 224001 17 SANT DNYANESHWAR Sant Nagar, Plot no-1/1, Sec No-4, Moshi Pune Maharashtra 412105 HOSPITAL PRIVATE LIMITED Pradhikaran,Pune-Nashik Highway, Spine Road 18 Lotus Hospital #389/3, Prem Nagar, Mata Road-122001 Gurugram Haryana 122001 19 Samyak Hospital BM-7 East Shalimar Bagh New Delhi Delhi 110088 20 Bristlecone Hospitals Pvt. -

Khir Bhawani Temple

Khir Bhawani Temple PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Kashmir: The Places of Worship Page Intentionally Left Blank ii KASHMIR NEWS NETWORK (KNN)). PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Kashmir: The Places of Worship KKaasshhmmiirr:: TThhee PPllaacceess ooff WWoorrsshhiipp First Edition, August 2002 KASHMIR NEWS NETWORK (KNN)) iii PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Kashmir: The Places of Worship Contents page Contents......................................................................................................................................v 1 Introduction......................................................................................................................1-2 2 Some Marvels of Kashmir................................................................................................2-3 2.1 The Holy Spring At Tullamulla ( Kheir Bhawani )....................................................2-3 2.2 The Cave At Beerwa................................................................................................2-4 2.3 Shankerun Pal or Boulder of Lord Shiva...................................................................2-5 2.4 Budbrari Or Beda Devi Spring..................................................................................2-5 2.5 The Chinar of Prayag................................................................................................2-6 -

Role of Dharmarth Trust (1846-1947A.D.) in the Shaping of Economic Policies of Dogra State

Role of Dharmarth Trust (1846-1947A.D.) in the Shaping of Economic Policies of Dogra State ISSN : 0972-7302 International Journal of Applied Business and Economic Research International Journal of Applied Business and ISSN : 0972-7302 Economic Research available at http: www.serialsjournals.com © Serials Publications Pvt. Ltd. SERIALS PUBLICATIONS PVT. LT D. Volume 15 • Number 21 (Part 2) • 2017 New Delhi, India Role of Dharmarth Trust (1846-1947A.D.) in the Shaping of Economic Policies of Dogra State Zahoor Ahmad Wani1 1Assistant Professor, Department of History, Lovely Professional University, Punjab. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The present paper is an effort that has been made to conduct a historical enquiry into significance of the economic activities of Dharmarth (1846-1947). Its activities were having great relevance in boosting the economy of Jammu and Kashmir State. Its efforts were directed towards the welfare of the inhabitants of the State irrespective of sex, creed and religion. It provided employment, loans, cash and land grants, charities etc. to the people at length. The land attached with temples and land granted to other religious functionaries and learned persons proved to be a viable economic source to the grantees as well as the tenants cultivating their land. The temples of pilgrimage, served an important source of economy to both the custodians and the local population with in their vicinity. Keywords: Dharmarth, Trust, Grants, Jammu and Kashmir, Custodian, Economic Policy, Mukarrari, Baridaras, Temple offerings, Takkavi Loans, Dogra State. 1. INTRODUCTION The importance that land commands in the economy of Jammu and Kashmir State can be judged from the fact that about 80 percent of the State’s population lives in rural areas whose primarily occupation was agriculture. -

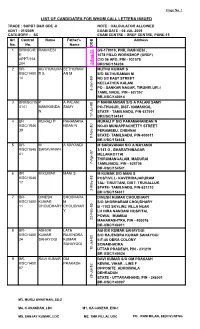

List of Candidates for Whom Call Letters Issued

Page No. 1 LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR WHOM CALL LETTERS ISSUED TRADE : SUPDT B&R GDE -II NOTE : CALCULATOR ALLOWED ADVT - 01/2009 EXAM DATE - 06 JUL 2009 CATEGORY - SC EXAM CENTRE - GREF CENTRE, PUNE-15 Srl Control Name Father's Address No. No. Name DOB 1 BRII/SC/R RAM KESI GS-179019, PNR, RAM KESI , E- 1078 FIELD WORKSHOP (GREF) APPT/154 C/O 56 APO, PIN - 931078 204 3-Aug-71 BRII/SC/154204 2 BR- MUTHUKUMA SETHURAM MUTHU KUMAR S II/SC/1400 R S AN M S/O SETHURAMAN M 14 NO 5/2 EAST STREET KEELATHEN KALAM PO - SANKAR NAGAR, TIRUNELUELI 8-Jan-80 TAMIL NADU, PIN - 627357 BR-II/SC/140014 3 BRII/SC/15 P A PALANI P MANIKANDAN S/O A PALANI SAMY 4141 MANIKANDA SAMY PO-THUSUR, DIST- NAMAKKAL N STATE - TAMILNADU, PIN-637001 17-Jul-88 BRII/SC/154141 4 BR MURALI P PARAMANA MURALI P S/O PARAMANANDAN N II/SC/1546 NDAN N NO-83 MUNIAPPACHETTY STREET 38 PERAMBEU, CHENNAI STATE- TAMILNADU, PIN-600011 9-Nov-80 BR II/SC/154638 5 BR- M A MAYANDI M SARAVANAN S/O A MAYANDI II/SC/1545 SARAVANAN 3/143 G , BHARATHINAGAR 41 MELAKKOTTAI THIRUMANGALAM, MADURAI 7-Apr-87 TAMILNADU, PIN - 625706 BR-II/SC/154541 6 BR M KUMAR MANI S M KUMAR S/O MANI S II/SC/1546 POST/VILL- KAVERIRAJAPURAM 17 TAL- TIRUTTANI, DIST- TRUVALLUR STATE- TAMILNADU, PIN-631210 2-May-83 BR II/SC/154617 7 BR- DINESH SHOBHARA DINESH KUMAR CHOUDHARY II/SC/1400 KUMAR M S/O SHOBHARAM CHOUDHARY 11 CHOUDHARY CHOUDHAR B -1102 SKYLINE VILLA NEAR Y LH HIRA NANDANI HOSPITAL POWAI, MUMBAI 22-Feb-85 MAHARASHTRA, PIN - 400076 BR-II/SC/140011 8 BR- ASHOK LATE ASHOK KUMAR SAHAYOGI II/SC/1400 KUMAR RAJENDRA S/O RAJENDRA KUMAR SAHAYOGI 24 SAHAYOGI KUMAR 5-F-46 OBRA COLONY SAHAYOGI SONABHADRA 10-Jul-82 UTTAR PRADESH, PIN - 231219 BR-II/SC/140024 9 BR- RAVI KUMAR OM RAVI KUMAR S/O OM PRAKASH II/SC/1400 PRAKASH KEWAL VIHAR , LINE F 07 OPPOSITE ADHOIWALA DEHRADUN 28-Jul-82 STATE - UTTARAKHAND, PIN - 248001 BR-II/SC/140007 M3. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25

NOTICE FOR APPOINTMENT OF REGULAR / RURAL RETAIL OUTLET DEALERSHIPS BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED (BPCL) PROPOSES TO APPOINT RETAIL OUTLET DEALERS IN THE STATE OF JAMMU AND KASHMIR AS PER FOLLOWING DETAILS: Estimated Fixed Fee / Security Minimum Dimension Type of monthly Type of Finance to be arranged by the Mode of Minimum Bid Deposit Sl. No Name of location Revenue District Category (in M.)/Area of the site (in Sq. RO Sales Site* applicant Selection amount (Rs.in (Rs.in M.). * Potential # Lakhs ) Lakhs ) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 CC / DC / SC CFS SC CC-1 SC CC-2 SC PH ST Estimated Estimated fund ST CC-1 working required for Regular / MS+HSD ST CC-2 capital Draw of Lots ST PH Frontage Depth Area development of Rural in Kls requirement / Bidding OBC infrastructure for operation OBC CC-1 at RO of RO OBC CC-2 OBC PH OPEN OPEN CC-1 OPEN CC-2 OPEN PH 1 Vill Khanpur on vijaypur to Khanpur road SAMBA RURAL 65 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 2 Village Madana, Purmandal Road SAMBA RURAL 60 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 3 VILLAGE DHOK JAGIR ON AKHNOOR TO KALEETH ROAD JAMMU RURAL 100 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 4 Village Nagrota(Between Ziyarat & Temple) LHS on Rajouri Budhal RoadRAJOURI RURAL 100 ST CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 5 Village Kotdhara (on Peeri to Rajouri Road) RAJOURI RURAL 30 ST CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 6 Village Magam on Magam to Pattan road BARAMULLA RURAL 75 ST CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 2 7 Hillar road, verinag to Qazigund ANANTNAG RURAL 50 ST CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of -

Under Government Orders

(Under Government Orders) BOMBAY PlUNTED AT THE GOVERNMENT CENTlUI. PRESS )btainable from the Government Publications Sales Depot, Institute of Science ' Building, Fort, Bombay (for purchasers in Bombay City); from the Government Book Depot, Chami Road Gardens, Bombay 4 (for orders from the mofussil) or I through the High Commissioner for India, India House, Aldwych, London. W.C.2 . or through any recognized Bookseller. Price-Re. 11 Anna.s 6 or 198. 1954 CONTENTS 1lJ. PAGB PREFACE v GENERAL INTRODUCTION • VII-X MAP. PART I. CHAPTER 1 : PHYSICAL FEATURES .urn NATURAL REsOURCES- 1 Boundaries and Sub-Divisions 1 ; ASpects 2 ; Hills 4 ; River Systems 6; Geology 10 ; Climate 11; Forests 20; Fauna 24 ; Birds 28; Fish 32; Snakes 37. PART n. CHAPTER 2: ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY- ,(1 Hindu Period ~90 B.C.-1295 A.D.) 41; Muslim Period (1295-1720) 43; Maratha Period \1720-1818) 52; British Period (1819-1947) 59. PART m. CIIAPTE~ 3: TIm, ~OPLE .AND Tm:m CULTURE-.- 69 Population' (1951 Census) 69; Food 75; Houses and Housing 76; Dress 78; Ornaments 21 ; Hindu CUstoms 82 ; Hindu Religious Practices 120;. Gaines 137; Dances 141; Akhadas or TaIims 145; ·Tamasha 146; Bene Israels'147; Christians 150; Muslims 153 ~ People from Tamil Nad 'and Kerala 157; Sindhi Hindus, 159. P~T IV....iECONOMIC ORGAN1ZAT~ON. CHAPTER 4: GENERAL ECONOMIC SURVEY .. 163 CHAPTER 5 : A~CULTUllE- 169 Agricultural .Popillation 169.; Rainfall 172; 'Agricultural Season 173; Soils 174; Land Utilization 177 j Holdings 183; Cereals 191; Pulses 196; Oil-Seeds 199; Drugs and Narcotics 201; Sugarcane 202; Condiments and Spices 204; Fibres 206; Fruits and Vegetables 207; AgricUltural. -

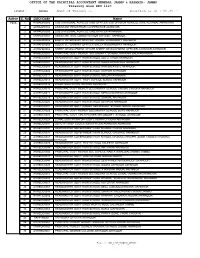

Treasury Wise DDO List Position As on : Name of Tresury

OFFICE OF THE PRINCIPAL ACCOUNTANT GENERAL JAMMU & KASHMIR- JAMMU Treasury wise DDO list Location : Jammu Name of Tresury :- Position as on : 09-JAN-17 Active S. No DDO-Code Name YES 1 AHBAGR0003 SUB DIVISIONAL AGRICULTURE OFFICER SUB DIVISION AGRICULTURE ACHABAL ANANTNAG 2 AKHAGR0002 ASSISTANT REGISTRAR COOPERATIVE AKHNOOR 3 AKHAGR0006 SUB DIVISIONAL AGRICULTURE OFFICER AKHNOOR . 4 AKHAGR0007 ASSISTANT SOIL CONSERVATION OFFICER AKHNOOR . 5 AKHAHD0002 BLOCK VETERINARY OFFICER ANIMAL HUSBANDRY AKHNOOR 6 AKHAHD0003 BLOCK VETERINARY OFFICER SHEEP HUSBANDARY AKHNOOR . 7 AKHAHD0004 SHEEP DEVELOPMENT OFICER SHEEP DEVELOPMENT OFFICER AKHNOOR AKHNOOR 8 AKHEDU0001 PRINCIPAL GOVT HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL NARRARI BALA AKHNOOR 9 AKHEDU0003 HEADMASTER GOVT HIGH SCHOOL KOTLI TANDA AKHNOOR 10 AKHEDU0004 HEADMASTER GOVT HIGH SCHOOL MAWA BRAHMANA AKHNOOR 11 AKHEDU0007 HEADMASTER GOVT HIGH SCHOOL RAH SALAYOTE AKHNOOR 12 AKHEDU0009 HEADMASTER GOVT HIGH SCHOOL KATHAR AKHNOOR 13 AKHEDU0011 HEADMASTER GOVT HIGH SCHOOL MALLAH AKHNOOR 14 AKHEDU0013 HEADMASTER GOVT HIGH SCHOOL SUNAIL AKHNOOR 15 AKHEDU0015 ZONAL EDUCATION OFFICER AKHNOOR . 16 AKHEDU0016 PRINCIPAL GOVT HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL CHOUKI CHOURA AKHNOOR 17 AKHEDU0017 HEADMASTER GOVT HIGH SCHOOL MERA MANDRIAN AKHNOOR 18 AKHEDU0018 HEADMASTER GOVT HIGH SCHOOL SUNGAL AKHNOOR 19 AKHEDU0020 HEADMASTER GOVT HIGH SCHOOL DEVIPUR AKHNOOR 20 AKHEDU0021 HEADMASTER GOVT HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL SOHAL AKHNOOR 21 AKHEDU0025 PRINCIPAL GOVT HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL BOYS AKHNOOR 22 AKHEDU0026 PRINCIPAL GOVT GIRLS HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL AKHNOOR 23 AKHEDU0028 ZONAL EDUCATION OFFICER CHOWKI CHOURA AKHNOOR 24 AKHEDU0031 DEPUTY CHIEF EDUCATION OFFICER AKHNOOR AKHNOOR 25 AKHEDU0034 HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL CHANG AKHNOOR . 26 AKHEDU0037 HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL GARKHAL AKHNOOR 27 AKHEDU0038 HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL DHANNA CHHAPRI (ZONE CHOWKI CHOURA) AKHNOOR 28 AKHEDU0039 HEADMASTER GOVT. -

Embedded Meanings an Analysis of the Role of the Raja in the Kulu Dussehra

Embedded Meanings An Analysis of the Role of the Raja in the Kulu Dussehra KARUNA GOSW AMY The focus of this paper revolves around the role of the Raja in Kulu Dussehra, an event that has long enjoyed the s tatus of a 'state festival' .' In the process one will be looking at a series of rituals and ceremonies that constitute, and are integral to, the performance of that role on the part of the Raja. One will also have to enter upon a rich description of the festival in some part, since de tail is of the essence for unde rstanding some of the 'statements' that are made through it and the implications that it holds. The description of some of the ritual acts will take centre stage, for rituals, as we well u_pderstand, are rich in resonances.2 For the purposes of the present study, as elsewhere, they would be seen to contain religious and cultural meanings, marking off and sanctifying s"cred spaces, establishing or confirming social re lations, articulating issues of rank and power. Authority, including in this case the authority of the Raja of Kulu, being central to ritual power, reference will be seen as constantly being made as Mubayi, (2005: 16-17) puts it to 'political linkages and hierarchies of privilege and status', as much as to 'structures of order and authority' .3 I The Dussehra of Kulu is visibly different, in so many ways, from the festival of the same name that is celebrated in large parts of northern India. Rama is here, as elsewhere, the central figure, and it is his triumph and glory in all its plenitude that one is reminded of, year after year, through the celebrations.