Nasa Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Oral History Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Much Have We Advanced?

English How much have Pedagogical Module 2 we advanced? Curricular Threads: Communication and Cultural Awareness, Oral Communication, Reading, Writing, Language Through the Arts First Course BGU Past perfect 5 Scientific inventions and Science 6 their impact on humanity Present perfect 4 Social Studies History of 7 inventions Simple past 3 Language Analyzing short Past and present English Technology 8 non-fiction pieces perfect expressions 2 and Beyond Vocabulary about technology and 1 inventions Values Importance Healthcare 10 9 of immunization Incredible Inventions Have you ever imagined a world without we have created powerful devices that allow cars or television? Imagine waiting for months us see the vast universe. to hear from your loved ones. Imagine getting sick and having no medicine. We are going Nowadays it is possible to video chat with to travel through history and observe human’s anyone anywhere for free. We have access infinite curiosity and inventions that have to infinite amounts of information and we can post changed the world. Discover creations that our own thoughts and opinions. Technology have shaped culture and lifestyle. Our brains has developed a lot during the last hundred years have even taken our people to the moon and and will continue to develop in the future. What positive and negative impacts have human inventions had? Non-Commercial Licence Non-Commercial 1 Lesson A Communication and Cultural Awareness Social Studies How have humans’ creations changed the world? Discoveries from Ancient Cultures Interesting Facts Believe it or not, people that lived many years ago invented things that are still used nowadays. -

Nasa Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Oral History 5 Transcript

NASA JOHNSON SPACE CENTER ORAL HISTORY PROJECT ORAL HISTORY 5 TRANSCRIPT JOSEPH P. ALLEN INTERVIEWED BY JENNIFER ROSS-NAZZAL MCLEAN, VIRGINIA – 18 APRIL 2006 The questions in this transcript were asked during an oral history session with Dr. Joseph P. Allen Dr. Allen has amended the answers for clarification purposes. As a result, this transcript does not exactly match the audio recording th ROSS-NAZZAL: Today is April 18 , 2006. This oral history with Joseph P. Allen is being conducted for the Johnson Space Center Oral History Project in McLean, Virginia. Jennifer Ross-Nazzal is the interviewer. Thanks again for joining me for our fifth session. ALLEN: Thank you, Jennifer, thank you. Is today the hundredth anniversary of the San Francisco earthquake? ROSS-NAZZAL: I think so, yes. ALLEN: A very interesting day today. ROSS-NAZZAL: I wanted to start, actually, by going back and asking you about something we should have talked about in your first interview, and that’s astronaut desert survival training in Washington that you participated in in 1967. ALLEN: Ah, yes. Well, I do have some recollection of it, and it’s just one of several survival schools that the early astronaut training had us go to. If memory serves me, one was water 18 April 2006 1 Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Joseph P. Allen survival, another was jungle survival, and then there was desert survival. I believe the desert survival may have been the first. The way NASA does that, of course, is they outsource it. They hire the military to provide military training, because the military runs survival schools on a very regular basis. -

Story Musgrave (M.D.) Nasa Astronaut (Former)

Biographical Data Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas 77058 National Aeronautics and Space Administration STORY MUSGRAVE (M.D.) NASA ASTRONAUT (FORMER) PERSONAL DATA: Born August 19, 1935, in Boston, Massachusetts, but considers Lexington, Kentucky, to be his hometown. Single. Six children (one deceased). His hobbies are chess, flying, gardening, literary criticism, microcomputers, parachuting, photography, reading, running, scuba diving, and soaring. EDUCATION: Graduated from St. Mark’s School, Southborough, Massachusetts, in 1953; received a bachelor of science degree in mathematics and statistics from Syracuse University in 1958, a master of business administration degree in operations analysis and computer programming from the University of California at Los Angeles in 1959, a bachelor of arts degree in chemistry from Marietta College in 1960, a doctorate in medicine from Columbia University in 1964, a master of science in physiology and biophysics from the University of Kentucky in 1966, and a master of arts in literature from the University of Houston in 1987. ORGANIZATIONS: Member of Alpha Kappa Psi, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Beta Gamma Sigma, the Civil Aviation Medical Association, the Flying Physicians Association, the International Academy of Astronautics, the Marine Corps Aviation Association, the National Aeronautic Association, the National Aerospace Education Council, the National Geographic Society, the Navy League, the New York Academy of Sciences, Omicron Delta Kappa, Phi Delta Theta, the Soaring Club of Houston, the Soaring Society of America, and the United States Parachute Association. SPECIAL HONORS: National Defense Service Medal and an Outstanding Unit Citation as a member of the United States Marine Corps Squadron VMA-212 (1954); United States Air Force Post-doctoral Fellowship (1965-1966); National Heart Institute Post-doctoral Fellowship (1966-1967); Reese Air Force Base Commander’s Trophy (1969); American College of Surgeons I.S. -

NASA History Fact Sheet

NASA History Fact Sheet National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Policy and Plans NASA History Office NASA History Fact Sheet A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION by Stephen J. Garber and Roger D. Launius Launching NASA "An Act to provide for research into the problems of flight within and outside the Earth's atmosphere, and for other purposes." With this simple preamble, the Congress and the President of the United States created the national Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) on October 1, 1958. NASA's birth was directly related to the pressures of national defense. After World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union were engaged in the Cold War, a broad contest over the ideologies and allegiances of the nonaligned nations. During this period, space exploration emerged as a major area of contest and became known as the space race. During the late 1940s, the Department of Defense pursued research and rocketry and upper atmospheric sciences as a means of assuring American leadership in technology. A major step forward came when President Dwight D. Eisenhower approved a plan to orbit a scientific satellite as part of the International Geophysical Year (IGY) for the period, July 1, 1957 to December 31, 1958, a cooperative effort to gather scientific data about the Earth. The Soviet Union quickly followed suit, announcing plans to orbit its own satellite. The Naval Research Laboratory's Project Vanguard was chosen on 9 September 1955 to support the IGY effort, largely because it did not interfere with high-priority ballistic missile development programs. -

Human Spaceflight. Activities for the Primary Student. Aerospace Education Services Project

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 288 714 SE 048 726 AUTHOR Hartsfield, John W.; Hartsfield, Kendra J. TITLE Human Spaceflight. Activities for the Primary Student. Aerospace Education Services Project. INSTITUTION National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Cleveland, Ohio. Lewis Research Center. PUB DATE Oct 85 NOTE 126p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Aerospace Education; Aerospace Technology; Educational Games; Elementary Education; *Elementary School Science; 'Science Activities; Science and Society; Science Education; *Science History; *Science Instruction; *Space Exploration; Space Sciences IDENTIFIERS *Space Travel ABSTRACT Since its beginning, the space program has caught the attention of young people. This space science activity booklet was designed to provide information and learning activities for students in elementary grades. It contains chapters on:(1) primitive beliefs about flight; (2) early fantasies of flight; (3) the United States human spaceflight programs; (4) a history of human spaceflight activity; (5) life support systems for the astronaut; (6) food for human spaceflight; (7) clothing for spaceflight and activity; (8) warte management systems; (9) a human space flight le;g; and (10) addition 1 activities and pictures. Also included is a bibliography of books, other publications and films, and the answers to the three word puzzles appearing in the booklet. (TW) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** HUMAN SPACEFLIGHT U.S DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION Activities CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproduced as mewed from the person or organization originating it Minor changes have been made to norm. -

A 2002 Profile In

UH Alumnus Makes First Trip to Space ByBy Brian Brian Allen Allen At T-minus six seconds, the main engines ignite. At T-minus zero, the solid rocket boosters light, the Shuttle begins to shake, and the ride of a lifetime begins. Astronaut Rex J. Walheim (1989 MSIE) has felt these sensations before—the G-forces and the shaking—but that was in the simulators. This time it’s real, and the 39-year-old Air Force lieutenant colonel knows his dream of space flight is finally becoming a reality. Walheim, who characterizes himself as a “window-seat” kind of guy, was determined to enjoy the spectacle of space travel—including the liftoff, which is normally difficult to view, even from the flight deck. “I had a little wrist mirror that I had on my left arm so I could look out the overhead window behind us, and when the main engines came up I could see the smoke from the exhaust coming up,” says Walheim. “A little later I looked up again and I could see the beach out the back window, and I could see it just fading away. It was just really amazing to see how fast we were climbing. You’re going about 100 mph by the time you clear the pad so it doesn’t take long. You’re really screamin’.” Walheim, a native of San Carlos, Calif., made his first trip to space last April, completing two successful spacewalks during NASA’s Atlantis STS-110 mission to the International Space Station. But he might never have made it to space, were it not for his decision in the mid eighties to pursue a master’s degree at the UH Cullen College of Engineering. -

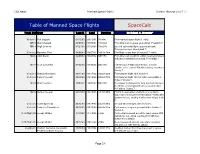

Table of Manned Space Flights Spacecalc

CBS News Manned Space Flights Current through STS-117 Table of Manned Space Flights SpaceCalc Total: 260 Crew Launch Land Duration By Robert A. Braeunig* Vostok 1 Yuri Gagarin 04/12/61 04/12/61 1h:48m First manned space flight (1 orbit). MR 3 Alan Shepard 05/05/61 05/05/61 15m:22s First American in space (suborbital). Freedom 7. MR 4 Virgil Grissom 07/21/61 07/21/61 15m:37s Second suborbital flight; spacecraft sank, Grissom rescued. Liberty Bell 7. Vostok 2 Guerman Titov 08/06/61 08/07/61 1d:01h:18m First flight longer than 24 hours (17 orbits). MA 6 John Glenn 02/20/62 02/20/62 04h:55m First American in orbit (3 orbits); telemetry falsely indicated heatshield unlatched. Friendship 7. MA 7 Scott Carpenter 05/24/62 05/24/62 04h:56m Initiated space flight experiments; manual retrofire error caused 250 mile landing overshoot. Aurora 7. Vostok 3 Andrian Nikolayev 08/11/62 08/15/62 3d:22h:22m First twinned flight, with Vostok 4. Vostok 4 Pavel Popovich 08/12/62 08/15/62 2d:22h:57m First twinned flight. On first orbit came within 3 miles of Vostok 3. MA 8 Walter Schirra 10/03/62 10/03/62 09h:13m Developed techniques for long duration missions (6 orbits); closest splashdown to target to date (4.5 miles). Sigma 7. MA 9 Gordon Cooper 05/15/63 05/16/63 1d:10h:20m First U.S. evaluation of effects of one day in space (22 orbits); performed manual reentry after systems failure, landing 4 miles from target. -

Toward a History of the Space Shuttle an Annotated Bibliography

Toward a History of the Space Shuttle An Annotated Bibliography Part 2, 1992–2011 Monographs in Aerospace History, Number 49 TOWARD A HISTORY OF THE SPACE SHUTTLE AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY, PART 2 (1992–2011) Compiled by Malinda K. Goodrich Alice R. Buchalter Patrick M. Miller of the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress NASA History Program Office Office of Communications NASA Headquarters Washington, DC Monographs in Aerospace History Number 49 August 2012 NASA SP-2012-4549 Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Space Shuttle Annotated Bibliography PREFACE This annotated bibliography is a continuation of Toward a History of the Space Shuttle: An Annotated Bibliography, compiled by Roger D. Launius and Aaron K. Gillette, and published by NASA as Monographs in Aerospace History, Number 1 in December 1992 (available online at http://history.nasa.gov/Shuttlebib/contents.html). The Launius/Gillette volume contains those works published between the early days of the United States’ manned spaceflight program in the 1970s through 1991. The articles included in the first volume were judged to be most essential for researchers writing on the Space Shuttle’s history. The current (second) volume is intended as a follow-on to the first volume. It includes key articles, books, hearings, and U.S. government publications published on the Shuttle between 1992 and the end of the Shuttle program in 2011. The material is arranged according to theme, including: general works, precursors to the Shuttle, the decision to build the Space Shuttle, its design and development, operations, and management of the Space Shuttle program. Other topics covered include: the Challenger and Columbia accidents, as well as the use of the Space Shuttle in building and servicing the Hubble Space Telescope and the International Space Station; science on the Space Shuttle; commercial and military uses of the Space Shuttle; and the Space Shuttle’s role in international relations, including its use in connection with the Soviet Mir space station. -

Pioneering Spirit

Marc: Pioneering Spirit , •• Members of the SU aerospace community say it's time to get back to basics-and explore the universe By David Marc 26 SYRAC U SE U N IV ERS I TY MAGAZ I NE Published by SURFACE, 2003 1 Syracuse University Magazine, Vol. 20, Iss. 3 [2003], Art. 9 Photos/ Art Courtesy of NASA n October 1957, the Soviet Union suc questions like, 'What kind of a universe have I got? cessfully launched Sputnik I, the first What's my place in it? What does it mean to be a I artificial satellite to orbit the Earth, human being?"' marking a beginning for what was Like many who have contributed to human space then called "the race fo r space." For many exploration, Musgrave worries about the American Americans, it was a particularly chilling moment in space program's future. "There's been no vision, no the Cold War, an unexpected indication that the trajectory, for quite some time," he says. "Columbia Communist superpower was overtaking the United highlights the problem." Indeed, when space shut States in science and technology. That following tle Columbia disintegrated upon re-entry into the spring, another significant event in the space race, atmosphere last February, killing its crew of seven in some ways even less expected, took place on the and shocking an already nervous nation on the Syracuse University campus. Franklin "Story" brink of war in Iraq, the volume was turned up on Musgrave '58, H'SS, who had been admitted to the a series of muted debates about the American mis University without a high school diploma, received sion in space that has been ongoing since the Apollo a B.S. -

*Pres Report 97

a Aeronautics Fiscal Year 1997 Activities Fiscal Year and Space Report of the President Fiscal Year 1997 Activities National Aeronautics and Space Administration Washington, DC 20546 b Aeronautics and Space Report of the President c Table of Contents 1997 Activities Fiscal Year National Aeronautics and Space Administration . 1 Department of Defense . 7 Federal Aviation Administration . 9 Department of Commerce . 13 Department of Energy . 17 Department of the Interior . 19 Department of Agriculture . 21 Federal Communications Commission . 23 National Science Foundation . 25 Smithsonian Institution . 27 Department of State . 29 Arms Control and Disarmament Agency . 31 U.S. Information Agency . 33 Appendices . 35 A-1 U.S. Government Spacecraft Record . 36 A-2 World Record of Space Launches Successful in Attaining Earth Orbit or Beyond . 37 B Successful Launches to Orbit on U.S. Launch Vehicles, October 1, 1996-September 30, 1997 . 38 C U.S. and Russian Human Space Flights, 1961-September 30, 1997 . 42 D U.S. Space Launch Vehicles . 58 E-1A Space Activities of the U.S. Government— Historical Budget Summaries in Real Year Dollars . 61 E-1B Space Activities of the U.S. Government— Historical Budget Summaries in Inflation-Adjusted Dollars . 62 E-2 Federal Space Activities Budget . 63 E-3 Federal Aeronautics Budget . 64 Glossary . 65 Index . 73 d The National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958 directed the annual Aeronautics and Space Report to include a "comprehensive description of the programmed activities and the accomplishments of all agencies of the United States in the field of aeronautics and space activities during the preceding calendar year." In recent years, the reports have been prepared on a fiscal year (FY) basis, consistent with the budgetary period now used in programs of the Aeronautics and Space Report of the President Federal Government. -

The Last of NASA's Original Pilot Astronauts

The Last of NASA’s Original Pilot Astronauts Expanding the Space Frontier in the Late Sixties David J. Shayler and Colin Burgess The Last of NASA’s Original Pilot Astronauts Expanding the Space Frontier in the Late Sixties David J. Shayler, F.B.I.S Colin Burgess Astronautical Historian Bangor Astro Info Service Ltd New South Wales Halesowen Australia West Midlands UK SPRINGER-PRAXIS BOOKS IN SPACE EXPLORATION Springer Praxis Books ISBN 978-3-319-51012-5 ISBN 978-3-319-51014-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-51014-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017934482 © Springer International Publishing AG 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Defining Nasa's Mission and America's Vision for The

DEFINING NASA’S MISSION AND AMERICA’S VISION FOR THE FUTURE OF SPACE EXPLORATION HEARINGS BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON NATIONAL SECURITY, INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS, AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE OF THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MAY 9 AND 19, 1997 Serial No. 105–84 Printed for the use of the Committee on Government Reform and Oversight ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 46–559 CC WASHINGTON : 1998 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate jul 14 2003 13:41 Jan 14, 2004 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 W:\DISC\46559 46559 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT DAN BURTON, Indiana, Chairman BENJAMIN A. GILMAN, New York HENRY A. WAXMAN, California J. DENNIS HASTERT, Illinois TOM LANTOS, California CONSTANCE A. MORELLA, Maryland ROBERT E. WISE, JR., West Virginia CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut MAJOR R. OWENS, New York STEVEN SCHIFF, New Mexico EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York CHRISTOPHER COX, California PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida GARY A. CONDIT, California JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York STEPHEN HORN, California THOMAS M. BARRETT, Wisconsin JOHN L. MICA, Florida ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, Washington, THOMAS M. DAVIS, Virginia DC DAVID M. MCINTOSH, Indiana CHAKA FATTAH, Pennsylvania MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland JOE SCARBOROUGH, Florida DENNIS J. KUCINICH, Ohio JOHN B. SHADEGG, Arizona ROD R.