Reactivity Series, Activity Series and Electrochemical Series Christopher Talbot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactivity Series and Galvanic Cells

Reactivity Series and Galvanic Cells CHEM 220 Laboratory Manual – 2012 Revision p. 1 CHEM 220 Laboratory Manual – 2012 Revision p. 2 Reactivity Series PROCEDURE Part 1. Reactivity Series of Metals 1. Collect 5 small pieces of each of the following metals, polish them with steel wool, rinse with DI water and place each in a separate test tube (20 test tubes total): • Copper • Magnesium • Lead • Zinc 2. For each metal, add about 1-2 mL of the following 0.1 M solutions containing the indicated cations. Add each solution to just one test tube of a particular metal; however, do NOT use the solution containing the ion of the metal. Properly label each tube with metal and solution contents. (You can use the chart below as a guide for setup.) + • Silver ions Ag (solution may be lower in concentration – will NOT affect results) • Hydrogen ions H+ • Copper (II) ions Cu2+ • Magnesium ions Mg2+ • Lead (II) ions Pb2+ • Zinc ions Zn2+ 3. Observe the appearance of the metals and solutions initially. Observe any changes that are taking place immediately. Allow the metals and solutions to react for 15 + minutes, and then observe changes that have occurred to the solutions. Record the data in your notebook with a similar table to the one below: Ion + + 2+ 2+ 2+ 2+ Metal Ag H Cu Mg Pb Zn Cu Mg Pb Zn 4. Based on the data collected in this part of the experiment, construct a Reactivity chart that puts the metals, including silver metal (& elemental hydrogen, H2) in order from most reactive metal (or element) to least reactive. -

![Frequency and Potential Dependence of Reversible Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Interconversion by [Fefe]-Hydrogenases](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3536/frequency-and-potential-dependence-of-reversible-electrocatalytic-hydrogen-interconversion-by-fefe-hydrogenases-623536.webp)

Frequency and Potential Dependence of Reversible Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Interconversion by [Fefe]-Hydrogenases

Frequency and potential dependence of reversible electrocatalytic hydrogen interconversion by [FeFe]-hydrogenases Kavita Pandeya,b, Shams T. A. Islama, Thomas Happec, and Fraser A. Armstronga,1 aInorganic Chemistry Laboratory, Department of Chemistry, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 3QR, United Kingdom; bSchool of Solar Energy, Pandit Deendayal Petroleum University, Gandhinagar 382007, Gujarat, India; and cAG Photobiotechnologie Ruhr–Universität Bochum, 44801 Bochum, Germany Edited by Thomas E. Mallouk, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, and approved March 2, 2017 (received for review December 5, 2016) The kinetics of hydrogen oxidation and evolution by [FeFe]- CrHydA1 contains only the H cluster: in the living cell, it receives hydrogenases have been investigated by electrochemical imped- electrons from photosystem I via a small [2Fe–2S] ferredoxin ance spectroscopy—resolving factors that determine the excep- known as PetF (19). No accessory internal Fe–S clusters are tional activity of these enzymes, and introducing an unusual and present to mediate or store electrons. powerful way of analyzing their catalytic electron transport prop- For enzymes, PFE has focused entirely on net catalytic electron erties. Attached to an electrode, hydrogenases display reversible flow that is observed as direct current (DC) in voltammograms + electrocatalytic behavior close to the 2H /H2 potential, making (2, 3, 10). Use of DC cyclic voltammetry as opposed to single them paradigms for efficiency: the electrocatalytic “exchange” rate potential sweeps alone helps to distinguish rapid, steady-state (measured around zero driving force) is therefore an unusual pa- catalytic activity at different potentials from relatively slow, rameter with theoretical and practical significance. Experiments potential-dependent changes in activity that are revealed as were carried out on two [FeFe]-hydrogenases, CrHydA1 from the hysteresis (10). -

Reactivity Series

Reactivity Series Observations of the way that these elements react with water, Acids and steam enable us to put them into this series. The tables show how the elements react with water and dilute acids: Element Reaction with water Potassium Violently Sodium Very quickly Lithium Quickly Calcium More slowly Element Reaction with dilute acids Calcium Very quickly Magnesium Quickly Zinc More slowly Iron More slowly than zinc Copper Very slowly Silver Barely reacts Gold Does not react Note that aluminium can be difficult to place in the correct position in the reactivity series during these experiments. This is because its protective aluminium oxide layer makes it appear to be less reactive than it really is. When this layer is removed, the observations are more reliable. It is useful to place carbon and hydrogen into the reactivity series because these elements can be used to extract metals. Displacement reactions of metal oxides A more reactive metal will displace a less reactive metal from a compound. The thermite reaction is a good example of this. It is used to produce white hot molten (liquid) iron in remote locations for welding. A lot of heat is needed to start the reaction, but then it releases an incredible amount of heat, enough to melt the iron. aluminium + iron(III) oxide → iron + aluminium oxide 2Al + Fe2O3 → 2Fe + Al2O3 Because aluminium is more reactive than iron, it displaces iron from iron(III) oxide. The aluminium removes oxygen from the iron(III) oxide: • iron is reduced • aluminium is oxidised Reactions between metals and metal oxides allow us to put a selection of metals into a reactivity series. -

Reactivity Series of Metals

Reactivity Series of Metals 1. Three experiments to investigate the reactivities of metals are shown below. Results of placing metal in a solution of Metal salt of chromium salt of manganese salt of iron Chromium No reaction No reaction Iron is displaced Chromium is Manganese No reaction Iron is displaced displaced Iron No reaction No reaction No reaction What is the order of reactivity of the metals? Most reactive Least reactive A Chromium Manganese Iron B Iron Chromium Manganese C Manganese Chromium Iron D Manganese Iron Chromium ( ) 2. The table shows the results of adding weighed pieces of zinc metal in salt solutions of metal P, Q and R. Salt solution of metal Initial mass of zinc / g Mass of zinc after 15 minutes / g P 5.0 0.0 Q 5.0 5.0 R 5.0 3.5 Which of the following shows the correct arrangement of metals in decreasing reactivity? A P, R, zinc, Q C Q, zinc, P, R B R, P, zinc, Q D Q, zinc, R, P ( ) 3. Which oxide can be reduced to its metal by carbon? A Calcium oxide C Magnesium oxide B Sodium oxide D Iron(II) oxide ( ) 4. Carbon can be used to reduce to its metal. A aluminium oxide C sodium oxide B lead(II) oxide D calcium oxide ( ) 5. Which statement about both lead and copper is correct? A They react with acid and hydrogen is released. B Their oxides can be reduced to metals using carbon. C Their sulfates dissolve in water. D All of their compounds are coloured. -

The Metal Reactivity Series

THE METAL REACTIVITY SERIES Metals can be ordered according to their reactivities; the table below shows a selection of common metals and their reactivities with water, air, and dilute acids. A more reactive metal will displace a less reactive metal from a compound. REACTION WITH REACTION WITH REACTION WITH REACTION WITH METAL NAME & SYMBOL COLD WATER STEAM AIR/OXYGEN DILUTE ACIDS EXTRACTION METHOD Produces metal hydroxide Produces metal oxide Produces metal oxide Produces metal salt & hydrogen & hydrogen & hydrogen POTASSIUM (K) VIOLENT REACTION VIOLENT REACTION REACTS READILY VIOLENT REACTION ELECTROLYSIS OF MOLTEN METAL ORE SODIUM (Na) STRONG REACTION VIOLENT REACTION REACTS READILY VIOLENT REACTION ELECTROLYSIS OF MOLTEN METAL ORE CALCIUM (Ca) MODERATE REACTION VIOLENT REACTION REACTS READILY VIOLENT REACTION ELECTROLYSIS OF MOLTEN METAL ORE LITHIUM (Li) MODERATE REACTION STRONG REACTION REACTS READILY VIGOROUS REACTION ELECTROLYSIS OF MOLTEN METAL ORE MAGNESIUM (Mg) VERY SLOW REACTION STRONG REACTION SLOW REACTION VIGOROUS REACTION ELECTROLYSIS OF MOLTEN METAL ORE ALUMINIUM (Al) NO REACTION MODERATE REACTION SLOW REACTION MODERATE REACTION ELECTROLYSIS OF MOLTEN METAL ORE (Carbon) ZINC (Zn) NO REACTION MODERATE REACTION REACTS WHEN HEATED MODERATE REACTION C METAL ORE SMELTED WITH CARBON IRON (Fe) NO REACTION REVERSIBLE REACTION REACTS WHEN HEATED MODERATE REACTION C METAL ORE SMELTED WITH CARBON NICKEL (Ni) NO REACTION SLOW REACTION REACTS WHEN HEATED SLOW REACTION C METAL ORE SMELTED WITH CARBON TIN (Sn) NO REACTION NO REACTION -

Reactivity Series of Metals

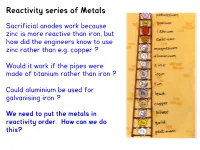

Reactivity series of Metals Sacrificial anodes work because zinc is more reactive than iron, but how did the engineers know to use zinc rather than e.g. copper ? Would it work if the pipes were made of titanium rather than iron ? Could aluminium be used for galvanising iron ? We need to put the metals in reactivity order. How can we do this? Key ideas: redox We already know of oxidation as the addition of oxygen and reduction as removal of oxygen, but this only one definition. A substance is oxidised if it loses electrons, and reduced if it gains electrons: xidation s oss O I L of electrons Reduction Is Gain Because when one substance loses electrons, another has to gain them, these are redox reactions. We can also define a reducing agent as a substance that causes another substance to gain electrons or lose oxygen, and an oxidising agent as a substance that causes another substance to lose electrons or gain oxygen. 1. Reactions of metals with water Reactive metals undergo a redox reaction with cold water. We have already seen this with the Group 1 metals, where we established the order: potassium > sodium > lithium e.g. 2 Li(s) + 2 H2O(l) à 2 LiOH(aq) + H2(g) In these reactions the metal atoms lose an electron to become a metal ion (being oxidised). The water is therefore the oxidising agent. The water loses oxygen (is reduced). Practical work: establish the reactivity order for lithium, magnesium and calcium by reacting similar size pieces with cold water. Conclusions: Calcium reacts exothermically with cold water, producing hydrogen gas. -

Computational Redox Potential Predictions: Applications to Inorganic and Organic Aqueous Complexes, and Complexes Adsorbed to Mineral Surfaces

Minerals 2014, 4, 345-387; doi:10.3390/min4020345 OPEN ACCESS minerals ISSN 2075-163X www.mdpi.com/journal/minerals Review Computational Redox Potential Predictions: Applications to Inorganic and Organic Aqueous Complexes, and Complexes Adsorbed to Mineral Surfaces Krishnamoorthy Arumugam and Udo Becker * Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Michigan, 1100 North University Avenue, 2534 C.C. Little, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1005, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-734-615-6894; Fax: +1-734-763-4690. Received: 11 February 2014; in revised form: 3 April 2014 / Accepted: 13 April 2014 / Published: 24 April 2014 Abstract: Applications of redox processes range over a number of scientific fields. This review article summarizes the theory behind the calculation of redox potentials in solution for species such as organic compounds, inorganic complexes, actinides, battery materials, and mineral surface-bound-species. Different computational approaches to predict and determine redox potentials of electron transitions are discussed along with their respective pros and cons for the prediction of redox potentials. Subsequently, recommendations are made for certain necessary computational settings required for accurate calculation of redox potentials. This article reviews the importance of computational parameters, such as basis sets, density functional theory (DFT) functionals, and relativistic approaches and the role that physicochemical processes play on the shift of redox potentials, such as hydration or spin orbit coupling, and will aid in finding suitable combinations of approaches for different chemical and geochemical applications. Identifying cost-effective and credible computational approaches is essential to benchmark redox potential calculations against experiments. -

Trends in Reactivity in the Periodic Table

Chemistry for the gifted and talented 35 Trends in reactivity in the Periodic Table Student worksheet: CDROM index 18SW Discussion of answers: CDROM index 18DA Topics Trends in reactivity of Groups 1 and 7 and the ionic bonding model. Level Very able students aged 14–16. Prior knowledge Ionic bonding and the Periodic Table. Rationale This activity aims to: • help students develop a tool (flowcharts) to aid organisation of their line of reasoning; • help students explore links between trends in the reactivity of Groups 1 and 7 and atomic structure; • give students the opportunity to use and critically evaluate the relevance of ionisation energy data to the reactivity series of metals; •reinforce the idea of chemical changes being driven by energy changes; and • challenge the idea that Group 1 metals want to give away their outer shell electron. Use This could be used to follow up some work on the Periodic Table where the trends in reactivity in Groups 1 and 7 have been identified. It can be used as a differentiated activity for the more able students within a group. When the students have completed the worksheet they should be given the Discussion of answers sheet. They could check their own work or conduct a peer review of the work of Chemistry for the gifted and talented Trends in reactivity in the Periodic Table Flow charts are sometimes a good way to organise your thoughts into a line of reasoning or logical argument. The example below is about the question of why Group 1 elements get more reactive as you go down the group. -

CHEMISTRY 130 Periodic Trends

CHEMISTRY 130 General Chemistry I Periodic Trends Elements within a period or group of the periodic table often show trends in physical and chemical properties. The variation in relative sizes of the halogens is shown above. DEPARTMENT OF CHEMISTRY UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS 1 Periodic Trends Introduction In the modern periodic table (shown below in Figure 1), elements are arranged according to increasing atomic number in horizontal rows called “periods.” In Figure 1, atomic numbers, which represent the number of protons in an atom of a given element, are listed directly above the element symbols. Figure 1: The modern periodic table. Elements in boxes shaded blue, orange, and purple are characterized as metals, metalloids, and nonmetals, respectively. The structure of the periodic table is such that elements with similar properties are aligned vertically in columns called “groups” or “families.” As indicated in Figure 1, each group has a number (1-18) associated with it. Select groups have also been assigned special names. For instance, the elements in Group 1 (hydrogen excluded) are called the alkali metals. These metallic elements react with oxygen to form bases. They also form alkaline (basic) solutions when mixed with water. Elements in other columns of the periodic table have also been given special “family” names. For instance, the elements in Groups 2, 11 (Cu, Ag, and Au), 16, 17, and 18 are commonly referred to as the alkaline earth metals, the coinage metals, the chalcogens, the halogens, and the noble gases, respectively. Many of these names reflect, unsurprisingly, the reactivity (or the lack thereof) of the elements found within the given group. -

"Relationships Between Oxidation-Reduction Potential

Relationships between Oxidation-Reduction Potential, Oxidant, and pH in Drinking Water Cheryl N. James3, Rachel C. Copeland2, and Darren A. Lytle1 1U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, NRMRL, Cincinnati, OH 2University of Cincinnati, Department of Environmental Engineering, Cincinnati, OH 3University of Cincinnati, Department of Chemical Engineering, Cincinnati, OH Abstract –Oxidation and reduction (redox) reactions are very important in drinking water. Oxidation-reduction potential (ORP) measurements reflect the redox state of water. Redox measurements are not widely made by drinking water utilities in part because they are not well understood. The objective of this study was to determine the effect of oxidant type and concentration on the ORP of carbonate buffered water as a function of pH. Oxidants that were studied included: chlorine, monochloramine, potassium permanganate, chlorine dioxide, and oxygen. ORP decreased with increasing pH, regardless of the oxidant type or concentration. ORP increased rapidly with increasing oxidant dosage, particularly at lower concentrations. Differences in the redox potentials of different oxidant systems were also observed. Waters that contained chlorine and chlorine dioxide had the highest ORPs. Tests also revealed that there were inconsistencies with redox electrode measurements. In the standard Zobell reference solution, two identical redox electrodes had nearly the same reading, but in test waters the readings sometimes showed a variation as great as 217.7 mV. Key words: ORP, redox potential, redox chemistry, oxidant, drinking water 1.0 BACKGROUND 1.1 Redox Theory Oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions describe the transfer of electrons between atoms, molecules, or ions. Oxidation and reduction reactions occur simultaneously and together make up an electrochemical couple. -

Ch.14-16 Electrochemistry Redox Reaction

Redox Reaction - the basics ox + red <=> red + ox Ch.14-16 1 2 1 2 Oxidizing Reducing Electrochemistry Agent Agent Redox reactions: involve transfer of electrons from one species to another. Oxidizing agent (oxidant): takes electrons Reducing agent (reductant): gives electrons Redox Reaction - the basics Balance Redox Reactions (Half Reactions) Reduced Oxidized 1. Write down the (two half) reactions. ox1 + red2 <=> red1 + ox2 2. Balance the (half) reactions (Mass and Charge): a. Start with elements other than H and O. Oxidizing Reducing Agent Agent b. Balance O by adding water. c. balance H by adding H+. Redox reactions: involve transfer of electrons from one d. Balancing charge by adding electrons. species to another. (3. Multiply each half reaction to make the number of Oxidizing agent (oxidant): takes electrons electrons equal. Reducing agent (reductant): gives electrons 4. Add the reactions and simplify.) Fe3+ + V2+ → Fe2+ + V3 + Example: Balance the two half reactions and redox Important Redox Titrants and the Reactions reaction equation of the titration of an acidic solution of Na2C2O4 (sodium oxalate, colorless) with KMnO4 (deep purple). Oxidizing Reagents (Oxidants) - 2- 2+ MnO4 (qa ) + C2O4 (qa ) → Mn (qa ) + CO2(g) (1)Potassium Permanganate +qa -qa 2-qa 16H ( ) + 2MnO4 ( ) + 5C2O4 ( ) → − + − 2+ 2+ MnO 4 +8H +5 e → Mn + 4 H2 O 2Mn (qa ) + 8H2O(l) + 10CO2( g) MnO − +4H+ + 3 e − → MnO( s )+ 2 H O Example: Balance 4 2 2 Sn2+ + Fe3+ <=> Sn4+ + Fe2+ − − 2− MnO4 + e→ MnO4 2+ - 3+ 2+ Fe + MnO4 <=> Fe + Mn 1 Important Redox Titrants -

Chemical Redox Agents for Organometallic Chemistry

Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 877−910 877 Chemical Redox Agents for Organometallic Chemistry Neil G. Connelly*,† and William E. Geiger*,‡ School of Chemistry, University of Bristol, U.K., and Department of Chemistry, University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont 05405-0125 Received October 3, 1995 (Revised Manuscript Received January 9, 1996) Contents I. Introduction 877 A. Scope of the Review 877 B. Benefits of Redox Agents: Comparison with 878 Electrochemical Methods 1. Advantages of Chemical Redox Agents 878 2. Disadvantages of Chemical Redox Agents 879 C. Potentials in Nonaqueous Solvents 879 D. Reversible vs Irreversible ET Reagents 879 E. Categorization of Reagent Strength 881 II. Oxidants 881 A. Inorganic 881 1. Metal and Metal Complex Oxidants 881 2. Main Group Oxidants 887 B. Organic 891 The authors (Bill Geiger, left; Neil Connelly, right) have been at the forefront of organometallic electrochemistry for more than 20 years and have had 1. Radical Cations 891 a long-standing and fruitful collaboration. 2. Carbocations 893 3. Cyanocarbons and Related Electron-Rich 894 Neil Connelly took his B.Sc. (1966) and Ph.D. (1969, under the direction Compounds of Jon McCleverty) degrees at the University of Sheffield, U.K. Post- 4. Quinones 895 doctoral work at the Universities of Wisconsin (with Lawrence F. Dahl) 5. Other Organic Oxidants 896 and Cambridge (with Brian Johnson and Jack Lewis) was followed by an appointment at the University of Bristol (Lectureship, 1971; D.Sc. degree, III. Reductants 896 1973; Readership 1975). His research interests are centered on synthetic A. Inorganic 896 and structural studies of redox-active organometallic and coordination 1.