The House I Live in Full Score

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MUNI 20151109 – Evergreeny 06 (Thomas „Fats“ Waller, Victor Young)

MUNI 20151109 – Evergreeny 06 (Thomas „Fats“ Waller, Victor Young) Honeysuckle Rose – dokončení z minulé přednášky Lena Horne 2:51 First published 1957. Nat Brandwynne Orchestra, conducted by Lennie Hayton. SP RCA 45-1120. CD Recall 305. Velma Middleton-Louis Armstrong 2:56 New York, April 26, 1955. Louis Armstrong and His All-Stars. LP Columbia CL 708. CD Columbia 64927 Ella Fitzgerald 2:20 Savoy Ballroom, New York, December 10, 1937. Chick Webb Orchestra. CD Musica MJCD 1110. Ella Fitzgerald 1:42> July 15, 1963 New York. Count Basie and His Orchestra. LP Verve V6-4061. CD Verve 539 059-2. Sarah Vaughan 2:22 Mister Kelly‟s, Chicago, August 6, 1957. Jimmy Jones Trio. LP Mercury MG 20326. CD EmArcy 832 791-2. Nat King Cole Trio – instrumental 2:32 December 6, 1940 Los Angeles. Nat Cole-piano, Oscar Moore-g, Wesley Prince-b. 78 rpm Decca 8535. CD GRP 16622. Jamey Aebersold 1:00> piano-bass-drums accompaniment. Doc Severinsen 3:43 1991, Bill Holman-arr. CD Amherst 94405. Broadway-Ain‟t Misbehavin‟ Broadway show. Ken Page, Nell Carter-voc. 2:30> 1978. LP RCA BL 02965. Sweet Sue, Just You (lyrics by Will J. Harris) - 1928 Fats Waller and His Rhythm: Herman Autrey-tp; Rudy Powell-cl, as; 2:55 Fats Waller-p,voc; James Smith-g; Charles Turner-b; Arnold Boling-dr. Camden, NJ, June 24, 1935. Victor 25087 / CD Gallerie GALE 412. Beautiful Love (Haven Gillespie, Wayne King, Egbert Van Alstyne) - 1931 Anita O’Day-voc; orchestra arranged and conducted by Buddy Bregman. 1:03> Los Angeles, December 6, 1955. -

Hearing Nostalgia in the Twilight Zone

JPTV 6 (1) pp. 59–80 Intellect Limited 2018 Journal of Popular Television Volume 6 Number 1 © 2018 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/jptv.6.1.59_1 Reba A. Wissner Montclair State University No time like the past: Hearing nostalgia in The Twilight Zone Abstract Keywords One of Rod Serling’s favourite topics of exploration in The Twilight Zone (1959–64) Twilight Zone is nostalgia, which pervaded many of the episodes of the series. Although Serling Rod Serling himself often looked back upon the past wishing to regain it, he did, however, under- nostalgia stand that we often see things looking back that were not there and that the past is CBS often idealized. Like Serling, many ageing characters in The Twilight Zone often sentimentality look back or travel to the past to reclaim what they had lost. While this is a perva- stock music sive theme in the plots, in these episodes the music which accompanies the scores depict the reality of the past, showing that it is not as wonderful as the charac- ter imagined. Often, music from these various situations is reused within the same context, allowing for a stock music collection of music of nostalgia from the series. This article discusses the music of nostalgia in The Twilight Zone and the ways in which the music depicts the reality of the harshness of the past. By feeding into their own longing for the reclamation of the past, the writers and composers of these episodes remind us that what we remember is not always what was there. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1950S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1950s Page 86 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1950 A Dream Is a Wish Choo’n Gum I Said my Pajamas Your Heart Makes / Teresa Brewer (and Put On My Pray’rs) Vals fra “Zampa” Tony Martin & Fran Warren Count Every Star Victor Silvester Ray Anthony I Wanna Be Loved Ain’t It Grand to Be Billy Eckstine Daddy’s Little Girl Bloomin’ Well Dead The Mills Brothers I’ll Never Be Free Lesley Sarony Kay Starr & Tennessee Daisy Bell Ernie Ford All My Love Katie Lawrence Percy Faith I’m Henery the Eighth, I Am Dear Hearts & Gentle People Any Old Iron Harry Champion Dinah Shore Harry Champion I’m Movin’ On Dearie Hank Snow Autumn Leaves Guy Lombardo (Les Feuilles Mortes) I’m Thinking Tonight Yves Montand Doing the Lambeth Walk of My Blue Eyes / Noel Gay Baldhead Chattanoogie John Byrd & His Don’t Dilly Dally on Shoe-Shine Boy Blues Jumpers the Way (My Old Man) Joe Loss (Professor Longhair) Marie Lloyd If I Knew You Were Comin’ Beloved, Be Faithful Down at the Old I’d Have Baked a Cake Russ Morgan Bull and Bush Eileen Barton Florrie Ford Beside the Seaside, If You were the Only Beside the Sea Enjoy Yourself (It’s Girl in the World Mark Sheridan Later Than You Think) George Robey Guy Lombardo Bewitched (bothered If You’ve Got the Money & bewildered) Foggy Mountain Breakdown (I’ve Got the Time) Doris Day Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs Lefty Frizzell Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo Frosty the Snowman It Isn’t Fair Jo Stafford & Gene Autry Sammy Kaye Gordon MacRae Goodnight, Irene It’s a Long Way Boiled Beef and Carrots Frank Sinatra to Tipperary -

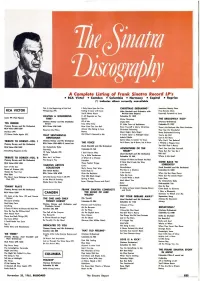

J2P and P2J Ver 1

inulTo discography A Complete Listing of Frank Sinatra Record LP's RCA Victor Camden Columbia Harmony Capitol Reprise ( *) indicates album currently unavailable Is This the Beginning of the End I Only Have Eyes for You CHRISTMAS DREAMING* American Beauty Rose Whispering RCA VICTOR (PP) Falling in Love with Love (Alex Stordahl and Orchestra with Five Minutes More You'll Never Know the Kea Lane Singers) Farewell, Farewell to Love HAVING A WONDERFUL It All Depends on You Columbia CL 1032 (note: PP -Pied Pipers) TIME* Spasm' White Christmas THE BROADWAY KICK* (Tommy Dorsey and His Clambake All of Me Jingle Bells (Various Orchestras) YES INDEED Seven) Time After Time O' Little Town of Bethlehem Columbia CL 1297 (Tommy Dorsey and His Orchestra) RCA Victor LPM 1643 How Cute Can You Be? Have Yourself a Merry Christmas There's No Business Like Show Business RCA Victor LPM 1229 Almost Like Being in Love Head on My Pillow Christmas Dreaming They Say It's Wonderful Stardust (PP) Nancy Silent Night, Holy Night Some Enchanted Evening I'll Never Smile Ohl What It Seemed to Me Again (PP) THAT SENTIMENTAL It Come Upon a Midnight Clear You're My Girl GENTLEMAN Adeste Fideles Lost in the Stars Santa Clous Is Conlin' to Town (Tommy Dorsey and His Orchestra) Can't You Behave? TRIBUTE TO DORSEY -VOL. 1 Let It Snow, let It RCA Victor LPM THE VOICE Snow, Let It Snow I Whistle a Happy Tune (Tommy Dorsey and His Orchestra) 6003 -2 record set (Axel Stordahl and His Orchestra) The Girl That I Marry RCA Victor LPM 1432 My Melancholy Baby ADVENTURES THE Can't You Just See Yourself Yearning Columbia CL 743 OF Everything Happens to Me HEART* There But For You Go I l'll Take Tallulah (PP) I Don't Know Why (Axel Stordahl and His Orchestra) Boli Ha'i Marie Try a Little Tenderness Columbia CL 953 Where Is My Bess? How Am Know TRIBUTE TO DORSEY -VOL. -

2Friday 1Thursday 3Saturday 4Sunday 5Monday 6Tuesday 7Wednesday 8Thursday 9Friday 10Saturday

JULY 2021 1THURSDAY 2FRIDAY DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME THEME: TCM BIRTHDAY TRIBUTE: WILLIAM WYLER KEEPING THE KIDS BUSY PRIMETIME THEME: PRIMETIME THEME: SELVIS FRIDAY NIGHT NEO-NOIR Seeing Double 8:00 PM Harper (‘66) 8:00 PM Kissin’ Cousins (‘64) 10:15 PM Point Blank (‘67) 10:00 PM Double Trouble (‘67) 12:00 AM Warning Shot (‘67) 12:00 AM Clambake (‘67) 2:00 AM Live A Little, Love a Little (‘68) 3SATURDAY 4SUNDAY DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME THEME: SATURDAY MATINEE HAPPY INDEPENDENCE DAY PRIMETIME THEME: PRIMETIME THEME: GABLE GOES WEST HAPPY INDEPENDENCE DAY 8:00 PM The Misfits (‘61) 8:00 PM Yankee Doodle Dandy (‘42) 10:15 PM The Tall Men (‘55) 10:15 PM 1776 (‘72) JULY JailhouseThes Stranger’s Rock(‘57) Return (‘33) S STAR OF THE MONTH: Elvis 5MONDAY 6TUESDAY 7WEDNESDAY P TCM SPOTLIGHT: Star Signs DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME AND PRIMETIME THEME(S): DAYTIME THEME: MEET CUTES DAYTIME THEME: TY HARDIN TCM PREMIERE PRIMETIME THEME: SOMETHING ON THE SIDE PRIMETIME THEME: DIRECTED BY BRIAN DE PALMA PRIMETIME THEME: THE GREAT AMERICAN MIDDLE TWITTER EVENTS 8:00 PM The Bonfire of the Vanities (‘90) PSTAR SIGNS Small Town Dramas NOT AVAILABLE IN CANADA 10:15 PM Obsession (‘76) Fire Signs 8:00 PM Peyton Place (‘57) 12:00 AM Sisters (‘72) 8:00 PM The Cincinnati Kid (‘65) 10:45 PM Picnic (‘55) 1:45 AM Blow Out (‘81) (Steeve McQueen – Aries) 12:45 AM East of Eden (‘55) 4:00 AM Body Double (‘84) 10:00 PM The Long Long Trailer (‘59) 3:00 AM Kings Row (‘42) (Lucille Ball – Leo) 5:15 AM Our Town (‘40) 12:00 AM The Bad and the Beautiful (‘52) (Kirk Douglas–Sagittarius) -

Palms to Pines Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan

Palms to Pines Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan PALMS TO PINES STATE SCENIC HIGHWAY CALIFORNIA STATE ROUTES 243 AND 74 June 2012 This document was produced by USDA Forest Service Recreation Solutions Enterprise Team with support from the Federal Highway Administration and in partnership with the USDA Forest Service Pacific Southwest Region, the Bureau of Land Management, the California Department of Transportation, California State University, Chico Research Foundation and many local partners. The USDA, the BLM, FHWA and State of California are equal opportunity providers and employers. In accordance with Federal law, U.S. Department of Agriculture policy and U.S. Department of Interior policy, this institution is prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age or disability. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720- 5964 (voice and TDD). Table of Contents Chapter 1 – The Palms to Pines Scenic Byway .........................................................................1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 Benefits of National Scenic Byway Designation .......................................................................... 2 Corridor Management Planning ................................................................................................. -

Elvis Quarterly 89 Ned

UEPS QUARTERLY 89 Driemaandelijks / Trimestriel januari-februari-maart 2009 / Afgiftekantoor Antwerpen X - erk. nr.: 708328 januari-februari-maart 2009 / Afgiftekantoor Antwerpen X - erk. nr.: Driemaandelijks / Trimestriel The United Elvis Presley Society is officieel erkend door Elvis en Elvis Presley Enterprises (EPE) sedert 1961 The United Elvis Presley Society Elvis Quarterly Franstalige afdeling: Driemaandelijks tijdschrift Jean-Claude Piret - Colette Deboodt januari-februari-maart 2009 Rue Lumsonry 2ème Avenue 218 Afgiftekantoor: Antwerpen X - 8/1143 5651 Tarcienne Verantwoordelijk uitgever: tel/fax 071 214983 Hubert Vindevogel e.mail: [email protected] Pijlstraat 15 2070 Zwijndrecht Rekeningnummers: tel/fax: 03 2529222 UEPS (lidgelden, concerten) e-mail: [email protected] 068-2040050-70 www.ueps.be TCB (boetiek): Voorzitter: 220-0981888-90 Hubert Vindevogel Secretariaat: Nederland: Martha Dubois Giro 2730496 (op naam van Hubert Vindevogel) IBAN: BE34 220098188890 – BIC GEBABEBB (boetiek) Medewerkers: IBAN: BE60 068204005070 – BIC GCCCBEBB (lidgelden – concerten) Tina Argyl Cecile Bauwens Showroom: Daniel Berthet American Dream Leo Bruynseels Dorp West 13 Colette Deboodt 2070 Zwijndrecht Pierre De Meuter tel: 03 2529089 (open op donderdag, vrijdag en zaterdag van 10 tot 18 uur Marc Duytschaever - Eerste zondag van elke maand van 13 tot 18 uur) Dominique Flandroit Marijke Lombaert Abonnementen België Tommy Peeters 1 jaar lidmaatschap: 18 € (vier maal Elvis Quarterly) Jean-Claude Piret 2 jaar: 32 € (acht maal Elvis Quarterly) Veerle -

Tommy Dorsey 1 9

Glenn Miller Archives TOMMY DORSEY 1 9 3 7 Prepared by: DENNIS M. SPRAGG CHRONOLOGY Part 1 - Chapter 3 Updated February 10, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS January 1937 ................................................................................................................. 3 February 1937 .............................................................................................................. 22 March 1937 .................................................................................................................. 34 April 1937 ..................................................................................................................... 53 May 1937 ...................................................................................................................... 68 June 1937 ..................................................................................................................... 85 July 1937 ...................................................................................................................... 95 August 1937 ............................................................................................................... 111 September 1937 ......................................................................................................... 122 October 1937 ............................................................................................................. 138 November 1937 ......................................................................................................... -

New on DVD & Blu-Ray

New On DVD & Blu-Ray The Magnificent Seven Collection The Magnificent Seven Academy Award® Winner* Yul Brynner stars in the landmark western that launched the film careers of Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson and James Coburn. Tired of being ravaged by marauding bandits, a small Mexican village seeks help from seven American gunfighters. Set against Elmer Bernstein’s Oscar® Nominated** score, director John Sturges’ thrilling adventure belongs in any Blu-ray collection. Return of the Magnificent Seven Yul Brynner rides tall in the saddle in this sensational sequel to The Magnificent Seven! Brynner rounds up the most unlikely septet of gunfighters—Warren Oates, Claude Akins and Robert Fuller among them—to search for their compatriot who has been taken hostage by a band of desperados. Guns of the Magnificent Seven This fast-moving western stars Oscar® Winner* George Kennedy as the revered—and feared—gunslinger Chris Adams! When a Mexican revolutionary is captured, his associates hire Adams to break him out of prison to restore hope to the people. After recruiting six experts in guns, knives, ropes and explosives, Adams leads his band of mercenaries on an adventure that will pit them against their most formidable enemy yet! *1967: Supporting Actor, Cool Hand Luke. The Magnificent Seven Ride! This rousing conclusion to the legendary Magnificent Seven series stars Lee Van Cleef as Chris Adams. Now married and working for the law, Adams’ settled life is turned upside-down when his wife is killed. Tracking the gunmen, he finds a plundered border town whose widowed women are under attack by ruthless marauders. -

1 307A Muggsy Spanier and His V-Disk All Stars Riverboat Shuffle 307A Muggsy Spanier and His V-Disk All Stars Shimmy Like My

1 307A Muggsy Spanier And His V-Disk All Stars Riverboat Shuffle 307A Muggsy Spanier And His V-Disk All Stars Shimmy Like My Sister Kate 307B Charlie Barnett and His Orch. Redskin Rhumba (Cherokee) Summer 1944 307B Charlie Barnett and His Orch. Pompton Turnpike Sept. 11, 1944 1 308u Fats Waller & his Rhythm You're Feets Too Big 308u, Hines & his Orch. Jelly Jelly 308u Fats Waller & his Rhythm All That Meat and No Potatoes 1 309u Raymond Scott Tijuana 309u Stan Kenton & his Orch. And Her Tears Flowed Like Wine 309u Raymond Scott In A Magic Garden 1 311A Bob Crosby & his Bob Cars Summertime 311A Harry James And His Orch. Strictly Instrumental 311B Harry James And His Orch. Flight of the Bumble Bee 311B Bob Crosby & his Bob Cars Shortin Bread 1 312A Perry Como Benny Goodman & Orch. Goodbye Sue July-Aug. 1944 1 315u Duke Ellington And His Orch. Things Ain't What They Used To Be Nov. 9, 1943 315u Duke Ellington And His Orch. Ain't Misbehavin' Nov. 9,1943 1 316A kenbrovin kellette I'm forever blowing bubbles 316A martin blanc the trolley song 316B heyman green out of november 316B robin whiting louise 1 324A Red Norvo All Star Sextet Which Switch Is Witch Aug. 14, 1944 324A Red Norvo All Star Sextet When Dream Comes True Aug. 14, 1944 324B Eddie haywood & His Orchestra Begin the Beguine 324B Red Norvo All Star Sextet The bass on the barroom floor 1 325A eddy howard & his orchestra stormy weather 325B fisher roberts goodwin invitation to the blues 325B raye carter dePaul cow cow boogie 325B freddie slack & his orchestra ella mae morse 1 326B Kay Starr Charlie Barnett and His Orch. -

Potomacpotomac Page 10

Wellbeing PotomacPotomac Page 10 Growing News, Page 2 Real Estate 8 Real Estate ❖ Classifieds, Page 11 Classifieds, ❖ Calendar, Page 6 Calendar, Bravo To Present ‘Annie Jr.’ And ‘Legally Blonde Jr.’ News, Page 3 Become a Court-Appointed Advocate for Children News, Page 3 Keeping Resolutions Wellbeing, Page 10 Photo Contributed Photo January 4-10, 2017 online at potomacalmanac.com www.ConnectionNewspapers.com Potomac Almanac ❖ January 4-10, 2017 ❖ 1 News Lower School Principal Margaret Andreadis with students. Bullis School second graders on a canoe trip encounter a frog. Bullis School To Add Kindergarten and First Grade To begin in the abstract, to develop good numerical sense and to communicate in speaking and September. writing. I teach the kids to select good books By Susan Belford and to read independently. I love experien- The Almanac tial learning and taking them to the C&O Canal to really experience nature, ecology ow far The Bullis School has and to appreciate the outdoors. I believe come since it was launched in that learning should be fun, engaging and H1930 as a one-year prepara- challenging and that the students should tory boarding school for high have the opportunity to be active agents in school graduates. Initially founded to pre- their learning.” pare young men for service academy en- He added, “Teaching this age group is trance exams, it opened in the former Bo- exhilarating because there is an incredible livian Embassy at 1303 New Hampshire range among the kids and the children are Ave. As enrollment increased, Bullis relo- so different from the beginning of the year cated in 1935 to the “country setting” of to the end. -

Pa Thin and the Ai

)ieS; Police, VS Officials the Authors. pa thin and the Ai. Is! more than s and Today serials To Set Policy al SAN magazines, Apo 35 JOSE, CALIFORNIA, WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 7, 1962 I. 50 No 36 "Mule Team," Ii. TEVE tault was not that 01 fraterni, eqUI11,1 mu I Ci01,111N gatherings '1',, daiter the circumstances men. "We are resolved that tas disperse noisy, unruly wrote members of the fraternal male', .1 state student:.. These occasions radio, surrounding Halloween's student, iklets and ad. were in line and were not resiaa, acre marked by drinking, violence, overall; riot and to determine an hale," declared the chief. "In fact. defiance of the police and arrests. Leads policy for future preven- Over effective at Nixon some fraternity members took Brown time. we expresed the San Jose "At that ,,,n of such incidents, a group of charge of dispersing the crowd." that the school administra- rf public rela- . opinion .-;.1S administrators, student lead- Dean Benz commended ASH tion should take a stronger position rid taught by President Bill Hauck and Inter- in dealing with delinquent students. :e also ers and San Jose police will as- taught fraternity Council President Dave We still feel that way. - semble in the recreation room of article writ. -Point; lA Loomis for assisting the police. Mid that the At Gains The editorial advocated Allen Hall at 3:30 p.m. today. , he suffered a administration "get tough with col- gan, NOT ISOLATED ISk BETTY 1,URRANO Republican, by 249,638 to 000 votes to Ralph Richardson's San Jose Police Chief Ray as disable, Chief Blackmore pointed out that legiate offenders and keep them Edmund G.