England Limits the Right to Silence and Moves Towards an Inquisitorial System of Justice Gregory W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STRUCTURING the PUBLIC DEFENDER Irene Oriseweyinmi Joe*

STRUCTURING THE PUBLIC DEFENDER Irene Oriseweyinmi Joe* ABSTRACT. The public defender may be critical to protecting individual rights in the U.S. criminal process, but state governments take remarkably different approaches to distributing the services. Some organize indigent defense as a function of the executive branch of state governance. Others administer the services through the judicial branch. The remaining state governments do not place it within any branch of state government, they delegate its management to local counties. This administrative choice has important implications for the public defender’s efficiency and effectiveness. It influences how the public defender will be funded and also the extent to which the public defender, as an institution, will respond to the particular interests of local communities. So, which branch of government should oversee the public defender? Should the public defender exist under the same branch of government that oversees the prosecutor and the police – two entities that the public defender seeks to hold accountable in the criminal process? Should the provision of services be housed under the judicial branch which is ordinarily tasked with being a neutral arbiter in criminal proceedings? Perhaps a public defender who is independent of statewide governance is ideal even if that might render it a lesser player among the many government agencies battling at the state level for limited financial resources. This article answers this question about state assignment by engaging in an original examination of each state’s architectural choices for the public defender. Its primary contribution is to enrich our current understanding of how each state manages the public defender function and how that decision influences the institution’s funding and ability to adhere to ethical and professional mandates. -

Defense Counsel in Criminal Cases by Caroline Wolf Harlow, Ph.D

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report November 2000, NCJ 179023 Defense Counsel in Criminal Cases By Caroline Wolf Harlow, Ph.D. Highlights BJS Statistician At felony case termination, court-appointed counsel represented 82% Almost all persons charged with a of State defendants in the 75 largest counties in 1996 felony in Federal and large State courts and 66% of Federal defendants in 1998 were represented by counsel, either Percent of defendants ù Over 80% of felony defendants hired or appointed. But over a third of Felons Misdemeanants charged with a violent crime in persons charged with a misdemeanor 75 largest counties the country’s largest counties and in cases terminated in Federal court Public defender 68.3% -- 66% in U.S. district courts had represented themselves (pro se) in Assigned counsel 13.7 -- Private attorney 17.6 -- publicly financed attorneys. court proceedings prior to conviction, Self (pro se)/other 0.4 -- as did almost a third of those in local ù About half of large county jails. U.S. district courts Federal Defender felony defendants with a public Organization 30.1% 25.5% defender or assigned counsel Indigent defense involves the use of Panel attorney 36.3 17.4 and three-quarters with a private publicly financed counsel to represent Private attorney 33.4 18.7 Self representation 0.3 38.4 lawyer were released from jail criminal defendants who are unable to pending trial. afford private counsel. At the end of Note: These data reflect use of defense counsel at termination of the case. -

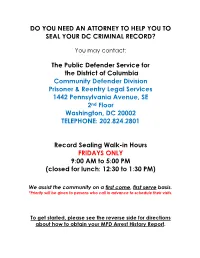

Do You Need an Attorney to Help You to Seal Your Dc Criminal Record?

DO YOU NEED AN ATTORNEY TO HELP YOU TO SEAL YOUR DC CRIMINAL RECORD? You may contact: The Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia Community Defender Division Prisoner & Reentry Legal Services 1442 Pennsylvania Avenue, SE 2nd Floor Washington, DC 20002 TELEPHONE: 202.824.2801 Record Sealing Walk-in Hours FRIDAYS ONLY 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM (closed for lunch: 12:30 to 1:30 PM) We assist the community on a first come, first serve basis. *Priority will be given to persons who call in advance to schedule their visits. To get started, please see the reverse side for directions about how to obtain your MPD Arrest History Report. To Get Started First Obtain Your “MPD Arrest History Report for the Purposes of the Criminal Sealing Act of 2006” Before anyone can determine your eligibility to file a motion to seal records and/or arrests, you need to obtain an MPD Arrest History Report for Purposes of the Criminal Record Sealing Act of 2006. Five Steps to Obtain Your MPD Arrest History Report 1. Bring with you ALL of the following items: a. A valid government-issued ID (such as a Driver’s License) b. $7.00 cash or money order to pay for the record c. Your social security number 2. Go to the Record Information Desk at the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD), located at 300 Indiana Avenue, NW, Criminal History Section, Room 1075 (On the 1st Floor). a. They are open Mon-Fri from 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. 3. Request a copy of your MPD Arrest History Report for Purposes of the Criminal Record Sealing Act of 2006. -

A Federal Criminal Case Timeline

A Federal Criminal Case Timeline The following timeline is a very broad overview of the progress of a federal felony case. Many variables can change the speed or course of the case, including settlement negotiations and changes in law. This timeline, however, will hold true in the majority of federal felony cases in the Eastern District of Virginia. Initial appearance: Felony defendants are usually brought to federal court in the custody of federal agents. Usually, the charges against the defendant are in a criminal complaint. The criminal complaint is accompanied by an affidavit that summarizes the evidence against the defendant. At the defendant's first appearance, a defendant appears before a federal magistrate judge. This magistrate judge will preside over the first two or three appearances, but the case will ultimately be referred to a federal district court judge (more on district judges below). The prosecutor appearing for the government is called an "Assistant United States Attorney," or "AUSA." There are no District Attorney's or "DAs" in federal court. The public defender is often called the Assistant Federal Public Defender, or an "AFPD." When a defendant first appears before a magistrate judge, he or she is informed of certain constitutional rights, such as the right to remain silent. The defendant is then asked if her or she can afford counsel. If a defendant cannot afford to hire counsel, he or she is instructed to fill out a financial affidavit. This affidavit is then submitted to the magistrate judge, and, if the defendant qualifies, a public defender or CJA panel counsel is appointed. -

20200122201324402 19-161 Bsac Scholars of the Law of Habeas Corpus.Pdf

No. 19-161 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY, et al., Petitioners, v. VIJAYAKUMAR THURAISSIGIAM, Respondent. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT BRIEF FOR SCHOLARS OF THE LAW OF HABEAS CORPUS AS AMICI CURIAE SUPPORTING RESPONDENT NOAH A. LEVINE Counsel of Record WILMER CUTLER PICKERING HALE AND DORR LLP 7 World Trade Center 250 Greenwich Street New York, NY 20007 (212) 230-8875 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ........................................... ii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE................................... 1 BACKGROUND .................................................................. 1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ................................. 3 ARGUMENT ........................................................................ 6 I. THE SUSPENSION CLAUSE GUARANTEES THE AVAILABILITY OF HABEAS TO NONCITIZENS WHO HAVE ENTERED THE UNITED STATES AND ARE DETAINED FOR THE PURPOSES OF REMOVAL ..................................... 6 II. CONGRESS’S POWER OVER IMMIGRATION DOES NOT ALLOW IT TO ENACT A DE FACTO SUSPENSION OF THE WRIT .......................... 11 III. SECTION 1252(e) IS RADICALLY INCONSISTENT WITH THE GUARANTEE OF THE SUSPENSION CLAUSE ........................................ 22 CONCLUSION ................................................................. 24 APPENDIX: List of Amici ............................................. 1a (i) ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CASES Page(s) Arabas v. Ivers, 1 Root 92 (Conn. -

You Have a Right to Remain Silent Michael Avery

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 30 | Number 2 Article 5 2003 You Have a Right to Remain Silent Michael Avery Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael Avery, You Have a Right to Remain Silent, 30 Fordham Urb. L.J. 571 (2002). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol30/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. You Have a Right to Remain Silent Cover Page Footnote The Author ppra eciates the advice of Professor Susan Klein, University of Texas Law School with respect to Fifth Amendment issues and the assistance of his colleague Professor Marie Ashe. The assistance of the Deans of Suffolk Law School with summer writing stipends made this work possible. This article is available in Fordham Urban Law Journal: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol30/iss2/5 YOU HAVE A RIGHT TO REMAIN SILENT Michael Avery* INTRODUCTION Everyone who watches television knows that when someone is arrested, the police have to "Mirandize"1 the suspect by reading his rights to him and that one of those rights is the "right to remain silent." The general public also knows that the suspect has the right to see a lawyer.2 Of course, in crime dramas these rights are often violated, but no one questions that they exist. -

Constitutional Law -- Criminal Law -- Habeas Corpus -- the 1963 Trilogy, 42 N.C

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 42 | Number 2 Article 9 2-1-1964 Constitutional Law -- Criminal Law -- Habeas Corpus -- The 1963 rT ilogy Robert Baynes Richard Dailey DeWitt cM Cotter Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert Baynes, Richard Dailey & DeWitt cM Cotter, Constitutional Law -- Criminal Law -- Habeas Corpus -- The 1963 Trilogy, 42 N.C. L. Rev. 352 (1964). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol42/iss2/9 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES AND COMMENTS Constitutional Law-Criminal Law-Habeas Corpus- The 1963 Trilogy A merely representative list, not intended to be exhaustive, of the allegations of denial of due process in violation of the fourteenth amendment which the Supreme Court has deemed cognizable on 1 2 habeas would include jury prejudice, use of coerced confessions, the knowing introduction of perjured testimony by the prosecution,8 mob domination of the trial,4 discrimination in jury selection" and denial of counsel.' And the currently expanding concepts of what constitutes due process of law will in the future present an even greater variety of situations in which habeas corpus will lie to test the constitutionality of state criminal proceedings.1 In 1963 the Supreme Court of the United States handed down three decisions which will greatly increase the importance of the writ of habeas corpus as a means of protecting the constitutional rights of those convicted of crimes. -

Grand Jury Duty in Ohio

A grand jury is an essential part of the legal system. What Is a Grand Jury? In Ohio, a grand jury decides whether the state Thank you for your willingness to help your has good enough reason to bring felony charges fellow citizens by serving as a grand juror. As against a person alleged to have committed a a former prosecuting attorney, I can attest crime. Felonies are serious crimes — ranging that you have been asked to play a vital role from murder, rape, other sexual assaults, and in American democracy. kidnapping to drug offenses, robbery, larceny, financial crimes, arson, and many more. The justice system in America and in Ohio cannot function properly without the The grand jury is an accusatory body. It does not dedication and involvement of its citizens. determine guilt or innocence. The grand jury’s I guarantee that when you come to the end duty is simply to determine whether there is of your time on the grand jury, you will sufficient evidence to make a person face criminal consider this service to have been one of the charges. The grand jury is designed to help the best experiences of your life. state proceed with a fair accusation against a person, while protecting that person from being Our society was founded on the idea of equal charged when there is insufficient evidence. justice under law, and the grand jury is a critical part of that system. Thank you again In Ohio, the grand jury is composed of nine for playing a key role in American justice. -

Reforming the Grand Jury Indictment Process

The NCSC Center for Jury Studies is dedicated to facilitating the ability of citizens to fulfill their role within the justice system and enhancing their confidence and satisfaction with jury service by helping judges and court staff improve jury system management. This document was prepared with support from a grant from the State Justice Institute (SJI-18-N-051). The points of view and opinions offered in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Center for State Courts or the State Justice Institute. NCSC Staff: Paula Hannaford-Agor, JD Caisa Royer, JD/PhD Madeline Williams, BS Allison Trochesset, PhD The National Center for State Courts promotes the rule of law and improves the administration of justice in state courts and courts around the world. Copyright 2021 National Center for State Courts 300 Newport Avenue Williamsburg, VA 23185-4147 ISBN 978-0-89656-316-2 Table of Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................1 What Is a Grand Jury?............................................................................................2 Special Duties .........................................................................................................3 Size Requirements...................................................................................................4 Term of Service and Quorum Requirements ...........................................................5 Reform -

Amended Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus to BE FILED

Case 2:19-cv-01263-JCC-MLP Document 6 Filed 08/13/19 Page 1 of 14 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 8 WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON AT SEATTLE 9 10 ELILE ADAMS, NO. 2:19-cv-01263 11 Petitioner, AMENDED PETITION FOR WRIT 12 OF HABEAS CORPUS v. 13 BILL ELFO, Whatcom County Sheriff; and 14 WENDY JONES, Whatcom County Chief of Corrections, 15 16 Respondents. 17 I. PETITION 18 1. Petitioner Elile Adams, a pretrial detainee in the custody of Whatcom County, 19 Washington, respectfully requests that this Court issue a writ of habeas corpus pursuant to 28 20 U.S.C. § 2241 and/or 25 U.S.C. § 1303. 21 II. PARTIES 22 2. Petitioner Elile Adams is a 33-year-old woman and Lummi Nation member who 23 resides on off-reservation trust lands at 7098 #4, Mission Road, Deming, Washington. She is not 24 an enrolled member of the Nooksack Indian Tribe. 25 AMENDED PETITION FOR WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS - 1 GALANDA BROADMAN, PLLC 8606 35th Avenue, NE, Ste. L1 Mailing: P.O. Box 15146 Seattle, Washington 98115 (206) 557-7509 Case 2:19-cv-01263-JCC-MLP Document 6 Filed 08/13/19 Page 2 of 14 1 3. Wendy Jones is the Whatcom County (“County”) Chief of Corrections. In that 2 position, Ms. Jones is responsible for administration and operations oversight for Whatcom 3 County Corrections Bureau, which includes the downtown County Jail (“Jail”), the Work Center, 4 and all of the jail-alternative programs that the County runs. -

In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: the Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis V

UIC Law Review Volume 44 Issue 2 Article 3 Winter 2011 In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: The Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis v. Thompkins, 44 J. Marshall L. Rev. 423 (2011) Harvey Gee Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Harvey Gee, In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: The Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis v. Thompkins, 44 J. Marshall L. Rev. 423 (2011) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol44/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN ORDER TO BE SILENT, YOU MUST FIRST SPEAK: THE SUPREME COURT EXTENDS DAVIS'S CLARITY REQUIREMENT TO THE RIGHT TO REMAIN SILENT IN BERGHUIS V. THOMPKINS HARVEY GEE* Criminal suspects must now unambiguously invoke their right to remain silent-which, counterintuitively, requires them to speak. .. suspects will be legally presumed to have waived their rights even if they have given clear expression of their intent to do so. Those results ... find no basis in Miranda... 1 I. INTRODUCTION At 3:09 a.m., two police officers escorted Richard Lovejoy, a suspect in an armed bank robbery, into a twelve-foot-square dimly lit interrogation room affectionately referred to as the "boiler room." This room is equipped with a two-way mirror in the wall for viewing lineups. -

20201209154816476 20-5133

No. 20-5133 ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES _______________ STEVEN BAXTER, PETITIONER v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA _______________ ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT _______________ BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES IN OPPOSITION _______________ JEFFREY B. WALL Acting Solicitor General Counsel of Record BRIAN C. RABBITT Acting Assistant Attorney General JOHN M. PELLETTIERI Attorney Department of Justice Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 [email protected] (202) 514-2217 ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ QUESTION PRESENTED Whether the court of appeals correctly determined that the warrantless search by federal customs officers of packages crossing the customs border between the United States customs territory and the United States Virgin Islands did not violate the Fourth Amendment. (I) ADDITIONAL RELATED PROCEEDINGS United States District Court (D.V.I.): United States v. Baxter, No. 17-cr-24 (Nov. 26, 2018) (order granting motion to suppress) United States Court of Appeals (3d Cir.): United States v. Baxter, No. 18-3613 (Feb. 21, 2020) (II) IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES _______________ No. 20-5133 STEVEN BAXTER, PETITIONER v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA _______________ ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT _______________ BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES IN OPPOSITION _______________ OPINIONS BELOW The opinion of the court of appeals (Pet. App. 3a-25a) is reported at 951 F.3d 128. The opinion of the district court (Pet. App. 28a-69a) is not published in the Federal Supplement but is available at 2018 WL 6173880.