Cowbridge & District Local History Society Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FOR SALE by PRIVATE TREATY Land Formerly Part of West Aberthaw Farm, Gileston, Vale of Glamorgan

FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY Land Formerly Part of West Aberthaw Farm, Gileston, Vale of Glamorgan An opportunity to acquire a block of approximately 25.79 Acres of Freehold Agricultural Land on the outskirts of the popular village of Gileston OFFERED AS ONE WHOLE OR IN TWO LOTS Guide Price: £200,000 (AS ONE WHOLE) www.wattsandmorgan.wales rural@ wattsandmorgan. wales 55 a High Street, Cowbridge, Vale of Glamorgan, CF71 7AE Tel: (01446) 774152 Fax: (01446) 775757 Email: [email protected] SITUATION FENCING AND BOUNDARIES The property is located on the outskirts of the Vale of The responsibility for boundaries are shown by the Glamorgan village of Gileston with St Athan Village to inward facing ‘T’ marks on the site plan. the north providing easy driving distance to Llantwit Major to the west and Barry to the east. There appears to be some livestock fencing around the external boundaries on the land but it is the DESCRIPTION responsibility of any potential purchasers to satisfy The property comprises approximately 25.79 acres of themselves as to the quality of this fencing. pasture land currently forming valuable grazing land but available for the growing of a variety of high Should the land be sold in two lots then the purchaser yielding arable crops etc. of Lot A will be responsible for providing a stockproof post and rylock stock fence between the posts X to Y on It has the benefit of road frontage and access ways and the site plan and maintaining same in perpetuity. we consider the present sale provides one with the opportunity of acquiring a useful block or blocks of land TENURE AND POSSESSION which subject to planning be suitable for a variety of Freehold with vacant possession upon completion. -

Handbook to Cardiff and the Neighborhood (With Map)

HANDBOOK British Asscciation CARUTFF1920. BRITISH ASSOCIATION CARDIFF MEETING, 1920. Handbook to Cardiff AND THE NEIGHBOURHOOD (WITH MAP). Prepared by various Authors for the Publication Sub-Committee, and edited by HOWARD M. HALLETT. F.E.S. CARDIFF. MCMXX. PREFACE. This Handbook has been prepared under the direction of the Publications Sub-Committee, and edited by Mr. H. M. Hallett. They desire me as Chairman to place on record their thanks to the various authors who have supplied articles. It is a matter for regret that the state of Mr. Ward's health did not permit him to prepare an account of the Roman antiquities. D. R. Paterson. Cardiff, August, 1920. — ....,.., CONTENTS. PAGE Preface Prehistoric Remains in Cardiff and Neiglibourhood (John Ward) . 1 The Lordship of Glamorgan (J. S. Corbett) . 22 Local Place-Names (H. J. Randall) . 54 Cardiff and its Municipal Government (J. L. Wheatley) . 63 The Public Buildings of Cardiff (W. S. Purchox and Harry Farr) . 73 Education in Cardiff (H. M. Thompson) . 86 The Cardiff Public Liljrary (Harry Farr) . 104 The History of iNIuseums in Cardiff I.—The Museum as a Municipal Institution (John Ward) . 112 II. —The Museum as a National Institution (A. H. Lee) 119 The Railways of the Cardiff District (Tho^. H. Walker) 125 The Docks of the District (W. J. Holloway) . 143 Shipping (R. O. Sanderson) . 155 Mining Features of the South Wales Coalfield (Hugh Brajiwell) . 160 Coal Trade of South Wales (Finlay A. Gibson) . 169 Iron and Steel (David E. Roberts) . 176 Ship Repairing (T. Allan Johnson) . 182 Pateift Fuel Industry (Guy de G. -

St. Athan - Howell's Well

Heritage Lottery Fund Suite 5A, Hodge House, Guildhall Place, Cardiff, CF10 1DY Directorate of Economic and Environmental Regeneration, Docks Office, Barry Dock, Vale of Glamorgan, CF63 4RT Conservation and Design Team, Docks Office, Barry Dock, Vale of Glamorgan, CF63 4RT CADW Welsh Assembly Government Plas Carew Unit 5/7 Cefn Coed Parc Nantgarw Cardiff CF15 7QQ Barry Community Enterprise Centre Skomer Road, Barry CF62 9DA Civic Trust for Wales Civic Trust for Wales 3rd Floor, Empire House, Mount Stuart Square Cardiff CF10 5FN The Penarth Society 3 Clive Place, Penarth, CF64 1AU Foreword For many years now the recording and protection afforded to the historic environment has been bound within the provisions of a number legislative Acts of Parliament. Indeed, the Vale of Glamorgan has over 100 Scheduled Ancient Monuments, over 700 Listed Buildings and 38 Conservation Areas that are afforded statutory protection by legislation. However, this system of statutory recognition, by its nature, only takes account of items of exceptional significance. Often there are locally important buildings that although acknowledged not to be of ‘national’ or ‘exceptional’ importance, are considered key examples of vernacular architecture or buildings, which have an important local history. It is these buildings which are often the main contributors to local distinctiveness, but which have to date, remained un-surveyed and afforded little recognition or protection. The original County Treasures project was published by the then South Glamorgan County Council in the late 1970’s. It was conceived as a locally adopted inventory of ‘special features’ in the former County area. However, as a result of local government restructuring, the changes to local authority boundaries, as well as changes in responsibilities and funding mechanisms the survey was never completed, and as a consequence was not comprehensive in its coverage. -

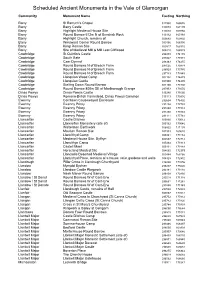

Scheduled Ancient Monuments in the Vale of Glamorgan

Scheduled Ancient Monuments in the Vale of Glamorgan Community Monument Name Easting Northing Barry St Barruch's Chapel 311930 166676 Barry Barry Castle 310078 167195 Barry Highlight Medieval House Site 310040 169750 Barry Round Barrow 612m N of Bendrick Rock 313132 167393 Barry Highlight Church, remains of 309682 169892 Barry Westward Corner Round Barrow 309166 166900 Barry Knap Roman Site 309917 166510 Barry Site of Medieval Mill & Mill Leat Cliffwood 308810 166919 Cowbridge St Quintin's Castle 298899 174170 Cowbridge South Gate 299327 174574 Cowbridge Caer Dynnaf 298363 174255 Cowbridge Round Barrows N of Breach Farm 297025 173874 Cowbridge Round Barrows N of Breach Farm 296929 173780 Cowbridge Round Barrows N of Breach Farm 297133 173849 Cowbridge Llanquian Wood Camp 302152 174479 Cowbridge Llanquian Castle 301900 174405 Cowbridge Stalling Down Round Barrow 301165 174900 Cowbridge Round Barrow 800m SE of Marlborough Grange 297953 173070 Dinas Powys Dinas Powys Castle 315280 171630 Dinas Powys Romano-British Farmstead, Dinas Powys Common 315113 170936 Ewenny Corntown Causewayed Enclosure 292604 176402 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291294 177788 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291260 177814 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291200 177832 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291111 177761 Llancarfan Castle Ditches 305890 170012 Llancarfan Llancarfan Monastery (site of) 305162 170046 Llancarfan Walterston Earthwork 306822 171193 Llancarfan Moulton Roman Site 307383 169610 Llancarfan Llantrithyd Camp 303861 173184 Llancarfan Medieval House Site, Dyffryn 304537 172712 Llancarfan Llanvithyn -

Planning Committee Report 24 February 2021

Agenda Item No. THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN COUNCIL PLANNING COMMITTEE : 24 FEBRUARY, 2021 REPORT OF THE HEAD OF REGENERATION AND PLANNING PLANNING APPLICATIONS Background Papers The following reports are based upon the contents of the Planning Application files up to the date of dispatch of the agenda and reports. 2020/00351/OUT Received on 1 April 2020 APPLICANT: Welsh Ministers c/o Agent AGENT: Miss Louise Darch WYG Planning and Environment, 5th Floor, Longcross Court, 47, Newport Road, Cardiff, CF24 0AD Land East of B4265 - Site A - Western Parcel, Llanmaes Outline planning permission with all matters reserved (other than existing access from Ffordd Bro Tathan) for residential development of up to 140 homes and associated development REASON FOR COMMITTEE DETERMINATION The application is required to be determined by Planning Committee under the Council’s approved scheme of delegation because the application is of a scale that is not covered by the scheme of delegation. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This is an outline planning application (with all matters reserved except ‘access’) for up to 140 dwellings on land adjacent to the Northern Access Road (Ffordd Bro Tathan), at the corner of Eglwys Brewis and Llantwit Major. The site lies within the settlement boundary of Llantwit Major and a Local Development Plan housing allocation. The proposal is for up to 140 dwellings, of which at least 35% would be affordable. Vehicular access would be directly from Ffordd Bro Tathan and the first part of the access into the site from the main road has already been constructed under planning permission 2017/00564/FUL ( i.e. -

Marriages by Bride Taken from the Glamorgan Gazette 1871

Marriages by Bride taken from the Glamorgan Gazette 1871 Bride's Bride's First Groom's Groom's First Date of Place of Marriage Other Information Date of Page Col Surname Name/s Surname Name/s Marriage Newspaper Arthur Margaret Thomas Edward 18/07/1871 Landow Both of Clemenstone. 28/07/1871 2 4 Service by the Rev. W. Edwards. Breins Minnie Reynolds George 09/04/1871 Groom schoolmaster of 21/04/1871 3 5 Maesteg. Minnie daughter of Mr. Brein Llynvi, Policeman. Cole Charlotte Strain James 12/05/1871 Hope Chapel, James mineral agent of 19/05/1871 2 5 Bridgend. Maesteg. Charlotte daughter of Rev. B. Cole of Maesteg. By license. David Anne Brunt Thomas 27/05/1871 All Saints Church Thomas only son of T. Brunt 02/06/1871 2 7 Windsor Berkshire of Windsor. Anne fourth daughter of Thomas David, farmer Coychurch. By license. David Elizabeth Morris Henry 22/01/1871 Coity Parish Church Groom - stoker Llynfi and 27/01/1871 2 4 Ogmore Railway Bride - youngest daughter of Edward David butcher Bridgend. By the Rev. David Roberts curate. David Jane Arr Dyer Jabez Henry 22/06/1871 Coity Groom of Bridgend. Bride 30/06/1871 2 5 fourth daughter of Evan David Builder Bridgend. By the Rev. D. Roberts Davies Catherine Lloyd Edmund 05/02/1871 Coity Catherine daughter of 10/02/1871 2 2 Morgan Davies Oldcastle Inn Bridgend. Groom of Heol Y Cawl near Bridgend. By license. Rev. David Roberts curate. Bride's Bride's First Groom's Groom's First Date of Place of Marriage Other Information Date of Page Col Surname Name/s Surname Name/s Marriage Newspaper Davis Mary Heater William 18/03/1871 Cowbridge Church Both of Cowbridge. -

FOLK-LORE and FOLK-STORIES of WALES the HISTORY of PEMBROKESHIRE by the Rev

i G-R so I FOLK-LORE AND FOLK-STORIES OF WALES THE HISTORY OF PEMBROKESHIRE By the Rev. JAMES PHILLIPS Demy 8vo», Cloth Gilt, Z2l6 net {by post i2(ii), Pembrokeshire, compared with some of the counties of Wales, has been fortunate in having a very considerable published literature, but as yet no history in moderate compass at a popular price has been issued. The present work will supply the need that has long been felt. WEST IRISH FOLK- TALES S> ROMANCES COLLECTED AND TRANSLATED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION By WILLIAM LARMINIE Crown 8vo., Roxburgh Gilt, lojC net (by post 10(1j). Cloth Gilt,3l6 net {by posi 3lio% In this work the tales were all written down in Irish, word for word, from the dictation of the narrators, whose name^ and localities are in every case given. The translation is closely literal. It is hoped' it will satisfy the most rigid requirements of the scientific Folk-lorist. INDIAN FOLK-TALES BEING SIDELIGHTS ON VILLAGE LIFE IN BILASPORE, CENTRAL PROVINCES By E. M. GORDON Second Edition, rez'ised. Cloth, 1/6 net (by post 1/9). " The Literary World says : A valuable contribution to Indian folk-lore. The volume is full of folk-lore and quaint and curious knowledge, and there is not a superfluous word in it." THE ANTIQUARY AN ILLUSTRATED MAGAZINE DEVOTED TO THE STUDY OF THE PAST Edited by G. L. APPERSON, I.S.O. Price 6d, Monthly. 6/- per annum postfree, specimen copy sent post free, td. London : Elliot Stock, 62, Paternoster Row, E.C. FOLK-LORE AND FOLK- STORIES OF WALES BY MARIE TREVELYAN Author of "Glimpses of Welsh Life and Character," " From Snowdon to the Sea," " The Land of Arthur," *' Britain's Greatness Foretold," &c. -

1869 Marriages by Groom Glamorgan Gazette

Marriages by groom taken from Glamorgan Gazette 1869 Groom’s Groom’s Bride’s Bride’s Date of Place of Marriage Other Information Date of Page Col Surname First name Surname First name Marriage newspaper Adare, Viscount Kerr Hon. 29/04/1869 St. Paul’s Church Groom – son of the Earl of 07/05/1869 4 1 Florence Knightsbridge Dunraven By special licence Bride – daughter of Lord & Lady Very Rev’d Charles Kerr Knotesford Fortescue Also see report page 4 col. 5 Archer Wm. E. Rees Mary 17/05/1869 Ruamah Baptist Groom – painter, Bridgend 21/05/1869 4 4 Chapel, Bridgend. Bride – eldest daughter of late Rev. J. Jenkins Wm. Rees, Newcastle Ash Evan Harding Anne 20/11/1869 Newton Nottage Both of Newton Nottage 26/11/1869 2 6 Church Rev. E.D. Knight Ayres William Lewis Jane 10/04/1869 Parish Church, Coity Groom – stonemason 16/04/1869 4 4 Rev. David Roberts, Both of Oldcastle, Bridgend curate Bassett Christopher Lewis Mary Jane 04/03/1869 Llandaff Cathedral. Groom – Great House, St. Mary 05/03/1869 4 7 By licence Hill, yeoman Bride – Canton nr. Cardiff – 2 nd daughter of late Wm. Lewis, Esq. formerly cashier Cyfarthfa Iron Works Bedford, Esq. Geo Rees, Mrs 16/11/1869 Salem Chapel Groom – Briton Ferry 19/11/1869 3 3 Pencoed Bride – Pyle Rev. D. Matthews By licence Bishop Thomas Rowland Dinah 05/06/1869 Baptist Chapel, Groom – second son of John 18/06/1869 4 2 Aberavon Bishop, fishmonger Rev. J. Griffiths Bride – for many years domestic servant of Evan Evans, Chemist, Aberavon Braddick Joseph Jones Mary 12/08/1869 Cardiff Groom – railway Inn, 20/08/1869 2 6 Cowbridge Bride – Masons Arms Inn, Cowbridge Bray John Morris Emma 18/05/1869 St. -

Cowbridge & District Local History Society Newsletter

COWBRIDGE & DISTRICT LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY NEWSLETTER No 57 : APRIL 2005 Fishtveir FUTURE MEETINGS Edward Bassett lived at Fishweir and was April ls‘: “In Search of Kenfig” - Dr Terry Robins described as being 'of Fishweir' when he Sept 2"d: AGM and “Where in Cowbridge is this?”- married Catherine Came of Nash Manor. The a picture quiz by Jeff Alden Summer excursion; probably at the end of May or Bassetts got into financial difficulties as a result in early June. Details in the April meeting of the Civil War, and were forced to sell up. The purchaser of the house and lands was Sir CHARTER DAY Edward Mansell of Margam. Neither he nor any member of his family resided at Fishweir; it Yvonne Weeding organised an excellent became a tenanted farm - perhaps fortunately celebration for Charter Day: a very good lunch for us, for the house was not modernised. It at the Bush Inn in St Hilary, followed by a visit was left to the Bevans, when they took over to Fishweir, on Monday 14th March. The Bush more than 20 years ago, to preserve all the early is a fine historic inn of mid-sixteenth century features which remain in the house. origins, and is now one of the few buildings in the Vale with the once ubiquitous thatched One of the rooms downstairs was in a roof. The two-centred arch stone doorways, soriy state with a vestigial stone staircase; the the stone staircase, and the great fireplace with room and the staircase have been rebuilt. The a hood supported on corbels are all features for two principal rooms were the kitchen and the the local historian to enjoy. -

Planning Committee Agenda

Agenda Item No. THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN COUNCIL PLANNING COMMITTEE : 28 MARCH, 2019 REPORT OF THE HEAD OF REGENERATION AND PLANNING 1. BUILDING REGULATION APPLICATIONS AND OTHER BUILDING CONTROL MATTERS DETERMINED BY THE HEAD OF REGENERATION AND PLANNING UNDER DELEGATED POWERS (a) Building Regulation Applications - Pass For the information of Members, the following applications have been determined: 2018/0647/BN A 38, Minehead Avenue, Rear single storey Sully extension 2018/1261/BN A Coach House, Adjacent to Conversion of existing 37 Salop Place, Penarth coach house into private use art studio space with storage mezzanine. To include WC and kitchenette facilities 2019/0082/BN A 41, Masefield Road, Change of bathroom to Penarth shower room 2019/0095/BN A 60, Marine Drive, Barry Replace 2 no. existing windows and central brick pillar on the front of the house with one large picture window, matching existing window design 2019/0129/BR AC Llangan Village Hall, Heol Proposed storeroom Llidiard, Llangan extension 2019/0137/BN A 8, Paget Road, Penarth Upstairs bathroom, extension over side return, remove three internal walls, put in sliding door and window, increase size of openings for windows upstairs on first and second floor 2019/0138/BN A 17, Carys Close, Penarth Porch including W.C. P.1 2019/0147/BN A Bryn Coed, Graig Penllyn, Conversion of existing Cowbridge garage into a utility room and W.C./shower room 2019/0149/BN A Danesacre, Claude Road Opening up existing West, Barry openings with universal beams at rear of house to make one large kitchen and diner 2019/0151/BR AC Lane End, Michaelston Le Construction of new barn Pit, Dinas Powys 2019/0152/BN A 58, Cornerswell Road, Single storey side Penarth extension to create open plan living/kitchen and use front room as new bedroom 2019/0155/BN A 16, Cherwell Road, Single rear and double side Penarth extensions 2019/0157/BR A 26, Ivy Street, Penarth Demolish existing conservatory. -

Cardiff North Hotel Thursday 24 October 2019 5.00Pm Circle Way East, Llanedeyrn Cardiff CF23 9XF Tel: 029 2058 9988

residential & commercial auction catalogue Wales & West Country Thursday 24 October 2019 5:00pm Important notes to be read by all bidders 1. Attention is drawn to the General Conditions of Sale printed 8. Reference made to any fixtures or fittings does not imply that within this catalogue. Special Conditions of Sale and supporting these are in working order and have not been tested by the documentation are available prior to the Auction from the Auctioneers or Agents instructed. Purchasers should establish Auctioneer’s Offices and will be available in the Auction Room the suitability and working condition of these appliances for inspection. Original documentation may be inspected for themselves. plan colouring etc. 9. No representation or warranty is made in respect of the 2. Any measurements or sizes referred to in the particulars are structure of any property nor in relation to the state of repair approximate and may be liable to slight variation. They are for thereof. The Auctioneers advise that prospective purchasers guidance only and do not form part of any contract. should arrange for a survey of the property to be under-taken by a professionally qualified person. 3. Any plans and photographs published are for the convenience of prospective purchasers and do not form part of any contract. 10. The Auctioneers reserve the right to amend the Order of Sale. Prospective purchasers intending to attend the Auction to bid 4. Leasehold information included in the catalogue or addendum are advised to contact the Auctioneers prior to the Auction to refers to current terms and may be subject to review or check whether the particular property has been withdrawn or increment. -

1871 Groom’S Groom’S Bride’S Bride’S Date of Place of Other Information Date Page Col Surname First Surname First Marriage Marriage Name Name Beavis T.W

Marriages by Groom taken from the Glamorgan Gazette 1871 Groom’s Groom’s Bride’s Bride’s Date of Place of Other Information Date Page Col Surname First Surname First Marriage Marriage name name Beavis T.W. Thomas Mary 14/12/1871 St. Brides Groom son of James Beavis. Bride 15/12/1871 3 4 Major Church. daughter of Evan Thomas of Longlands. By licence by the Rev. T. Jones. Bradley William Pritchard Blanche 25/05/1871 Llantrisant William of Cardiff. Blanche second daughter 02/06/1871 2 7 B. Parish Church of William Pritchard J.P. of Crofta. By the Rev. J. Williams vicar of Pendoylan, assisted by the Rev. J. Powell Jones and the Rev. D. Nicholl. Brown John Thomson Miss E. 13/04/1871 Coity Church John of Morfa Terrace Bridgend. Bride of 14/04/1871 3 7 New Abbey, Scotland. Brunt Thomas David Anne 27/05/1871 All Saints Thomas only son of T. Brunt of Windsor. 02/06/1871 2 7 Church Anne fourth daughter of Thomas David, Windsor farmer Coychurch. By license. Berkshire David Edward Innes Jane 21/12/1870 Bethal By license with the Rev. W. Joseph. Groom 06/01/1871 2 5 Sinclair Calvanistic of Bridgewater. Bride of Porthcawl. Methodist chapel Porthcawl David Jenkin Morgan Jane 03/01/1871 Bridgend Before David Lloyd registrar. Groom of 06/01/1871 2 5 Register Office Aberkenfig, late of Cowbridge. Bride of Royal Oak, Aberkenfig. Davies Daniel Lloyd Miss 01/06/1871 Ewenny Groom of Ewenny. Bride of Corntown. 02/06/1871 2 7 Davies John Roberts Annie 21/11/1871 St.