Volumetric Capnography 2 Expiredco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effect of an Indwelling Pleural Catheter Vs Talc Pleurodesis On

This supplement contains the following items: 1. Original protocol, final protocol, summary of changes. 2. Original statistical analysis plan. There were no further changes to the original statistical analysis plan. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/02/2021 The Australasian Malignant Pleural Effusion Trial (AMPLE) A Multicentre Randomized Study Comparing Indwelling Pleural Catheter vs Talc Pleurodesis in Patients with Malignant Pleural Effusions Ethics Registration number 2012-005 Protocol version number 1.0 Protocol date 10/01/2012 Authorised by: Name: Prof YC Gary Lee Role: Chief Investigator Signature: Date: 10/01/2012 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/02/2021 General Information This document describes the Western Australian Randomised Malignant Effusion trial for the purpose of submission for review by the relevant human research and ethics committees. It provides information about procedures for entering patients into the trial and this protocol should not be used as a guide for the treatment of other patients; every care was taken in its drafting, but corrections or amendments may be necessary. Questions or problems relating to this study should be referred to the Chief Investigator or Trial Coordinator. Compliance The trial will be conducted in compliance with this protocol, the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research, data protection laws and other guidelines as appropriate. It will be registered with the Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, once ethical approval is secured. -

Assessment Report COVID-19 Vaccine Astrazeneca EMA/94907/2021

29 January 2021 EMA/94907/2021 Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) Assessment report COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca Common name: COVID-19 Vaccine (ChAdOx1-S [recombinant]) Procedure No. EMEA/H/C/005675/0000 Note Assessment report as adopted by the CHMP with all information of a commercially confidential nature deleted. Official address Domenico Scarlattilaan 6 ● 1083 HS Amsterdam ● The Netherlands Address for visits and deliveries Refer to www.ema.europa.eu/how-to-find-us Send us a question Go to www.ema.europa.eu/contact Telephone +31 (0)88 781 6000 An agency of the European Union © European Medicines Agency, 2021. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Table of contents 1. Background information on the procedure .............................................. 7 1.1. Submission of the dossier ..................................................................................... 7 1.2. Steps taken for the assessment of the product ........................................................ 9 2. Scientific discussion .............................................................................. 12 2.1. Problem statement ............................................................................................. 12 2.1.1. Disease or condition ........................................................................................ 12 2.1.2. Epidemiology and risk factors ........................................................................... 12 2.1.3. Aetiology and pathogenesis ............................................................................. -

Effect of Heliox Breathing on Flow Limitation in Chronic Heart Failure Patients

Eur Respir J 2009; 33: 1367–1373 DOI: 10.1183/09031936.00117508 CopyrightßERS Journals Ltd 2009 Effect of heliox breathing on flow limitation in chronic heart failure patients M. Pecchiari*, T. Anagnostakos#, E. D’Angelo*, C. Roussos#, S. Nanas# and A. Koutsoukou# ABSTRACT: Patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) exhibit orthopnoea and tidal expiratory flow AFFILIATIONS limitation in the supine position. It is not known whether the flow-limiting segment occurs in the *Istituto di Fisiologia Umana I, Universita` degli Studi di Milano, peripheral or central part of the tracheobronchial tree. The location of the flow-limiting segment Milan, Italy, and can be inferred from the effects of heliox (80% helium/20% oxygen) administration. If maximal #Dept of Critical Care and Pulmonary expiratory flow increases with this low-density mixture, the choke point should be located in the Services, Evangelismos General central airways, where the wave-speed mechanism dominates. If the choke point were located in Hospital, Medical School, University of Athens, Athens, Greece. the peripheral airways, where maximal flow is limited by a viscous mechanism, heliox should have no effect on flow limitation and dynamic hyperinflation. CORRESPONDENCE Tidal expiratory flow limitation, dynamic hyperinflation and breathing pattern were assessed in M. Pecchiari 14 stable CHF patients during air and heliox breathing at rest in the sitting and supine position. Istituto di Fisiologia Umana I via L. Mangiagalli 32 No patient was flow-limited in the sitting position. In the supine posture, eight patients exhibited 20133 Milan tidal expiratory flow limitation on air. Heliox had no effect on flow limitation and dynamic Italy hyperinflation and only minor effects on the breathing pattern. -

Noninvasive Positive Pressure Ventilation in the Home

Technology Assessment Program Noninvasive Positive Pressure Ventilation in the Home Final Technology Assessment Project ID: PULT0717 2/4/2020 Technology Assessment Program Project ID: PULT0717 Noninvasive Positive Pressure Ventilation in the Home (with addendum) Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 www.ahrq.gov Contract No: HHSA290201500013I_HHSA29032004T Prepared by: Mayo Clinic Evidence-based Practice Center Rochester, MN Investigators: Michael Wilson, M.D. Zhen Wang, Ph.D. Claudia C. Dobler, M.D., Ph.D Allison S. Morrow, B.A. Bradley Beuschel, B.S.P.H. Mouaz Alsawas, M.D., M.Sc. Raed Benkhadra, M.D. Mohamed Seisa, M.D. Aniket Mittal, M.D. Manuel Sanchez, M.D. Lubna Daraz, Ph.D Steven Holets, R.R.T. M. Hassan Murad, M.D., M.P.H. Key Messages Purpose of review To evaluate home noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) in adults with chronic respiratory failure in terms of initiation, continuation, effectiveness, adverse events, equipment parameters and required respiratory services. Devices evaluated were home mechanical ventilators (HMV), bi-level positive airway pressure (BPAP) devices, and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices. Key messages • In patients with COPD, home NIPPV as delivered by a BPAP device (compared to no device) was associated with lower mortality, intubations, hospital admissions, but no change in quality of life (low to moderate SOE). NIPPV as delivered by a HMV device (compared individually with BPAP, CPAP, or no device) was associated with fewer hospital admissions (low SOE). In patients with thoracic restrictive diseases, HMV (compared to no device) was associated with lower mortality (low SOE). -

Ventilation Recommendations Table

SURVIVING SEPSIS CAMPAIGN INTERNATIONAL GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SEPTIC SHOCK AND SEPSIS-ASSOCIATED ORGAN DYSFUNCTION IN CHILDREN VENTILATION RECOMMENDATIONS TABLE RECOMMENDATION #34 STRENGTH & QUALITY OF EVIDENCE We were unable to issue a recommendation about whether to Insufficient intubate children with fluid-refractory, catecholamine-resistant septic shock. However, in our practice, we commonly intubate children with fluid-refractory, catecholamine-resistant septic shock without respiratory failure. RECOMMENDATION #35 STRENGTH & QUALITY OF EVIDENCE We suggest not to use etomidate when intubating children • Weak with septic shock or other sepsis-associated organ dysfunction. • Low-Quality of Evidence RECOMMENDATION #36 STRENGTH & QUALITY OF EVIDENCE We suggest a trial of noninvasive mechanical ventilation (over • Weak invasive mechanical ventilation) in children with sepsis-induced • Very Low-Quality of pediatric ARDS (PARDS) without a clear indication for intubation Evidence and who are responding to initial resuscitation. © 2020 Society of Critical Care Medicine and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Care Medicine. RECOMMENDATION #37 STRENGTH & QUALITY OF EVIDENCE We suggest using high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) • Weak in children with sepsis-induced PARDS. Remarks: The exact level • Very Low-Quality of of high PEEP has not been tested or determined in PARDS Evidence patients. Some RCTs and observational studies in PARDS have used and advocated for use of the ARDS-network PEEP to Fio2 grid though adverse hemodynamic effects of high PEEP may be more prominent in children with septic shock. RECOMMENDATION #38 STRENGTH & QUALITY OF EVIDENCE We cannot suggest for or against the use of recruitment Insufficient maneuvers in children with sepsis-induced PARDS and refractory hypoxemia. -

The Basics of Ventilator Management Overview How We Breath

3/23/2019 The Basics of Ventilator Management What are we really trying to do here Peter Lutz, MD Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Pulmonary Associates, Mobile, Al Overview • Approach to the physiology of the lung and physiological goals of mechanical Ventilation • Different Modes of Mechanical Ventilation and when they are indicated • Ventilator complications • Ventilator Weaning • Some basic trouble shooting How we breath http://people.eku.edu/ritchisong/301notes6.htm 1 3/23/2019 How a Mechanical Ventilator works • The First Ventilator- the Iron Lung – Worked by creating negative atmospheric pressure around the lung, simulating the negative pressure of inspiration How a Mechanical Ventilator works • The Modern Ventilator – The invention of the demand oxygen valve for WWII pilots if the basis for the modern ventilator https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcRI5v-veZULMbt92bfDmUUW32SrC6ywX1vSzY1xr40aHMdsCVyg6g How a Mechanical Ventilator works • The Modern Ventilator – How it works Inspiratory Limb Flow Sensor Ventilator Pressure Sensor Expiratory Limb 2 3/23/2019 So what are the goals of Mechanical Ventilation • What are we trying to control – Oxygenation • Amount of oxygen we are getting into the blood – Ventilation • The movement of air into and out of the lungs, mainly effects the pH and level of CO 2 in the blood stream Lab Oxygenation Ventilation Pulse Ox Saturation >88-90% Arterial Blood Gas(ABG) Po 2(75-100 mmHg) pCO 2(40mmHg) pH(~7.4) Oxygenation How do we effect Oxygenation • Fraction of Inspired Oxygen (FIO 2) – Percentage of the gas mixture given to the patient that is Oxygen • Room air is 21% • On the vent ranges from 30-100% • So if the patient’s blood oxygen levels are low, we can just increase the amount of oxygen we give them 3 3/23/2019 How do we effect Oxygenation • Positive End Expiratory Pressure (PEEP) – positive pressure that will remains in the airways at the end of the respiratory cycle (end of exhalation) that is greater than the atmospheric pressure in mechanically ventilated patients. -

Mechanical Ventilation Bronchodilators

A Neurosurgeon’s Guide to Pulmonary Critical Care for COVID-19 Alan Hoffer, M.D. Chair, Critical Care Committee AANS/CNS Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care Co-Director, Neurocritical Care Center Associate Professor of Neurosurgery and Neurology Rana Hejal, M.D. Medical Director, Medical Intensive Care Unit Associate Professor of Medicine University Hospitals of Cleveland Case Western Reserve University To learn more, visit our website at: www.neurotraumasection.org Introduction As the number of people infected with the novel coronavirus rapidly increases, some neurosurgeons are being asked to participate in the care of critically ill patients, even those without neurological involvement. This presentation is meant to be a basic guide to help neurosurgeons achieve this mission. Disclaimer • The protocols discussed in this presentation are from the Mission: Possible program at University Hospitals of Cleveland, based on guidelines and recommendations from several medical societies and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). • Please check with your own hospital or institution to see if there is any variation from these protocols before implementing them in your own practice. Disclaimer The content provided on the AANS, CNS website, including any affiliated AANS/CNS section website (collectively, the “AANS/CNS Sites”), regarding or in any way related to COVID-19 is offered as an educational service. Any educational content published on the AANS/CNS Sites regarding COVID-19 does not constitute or imply its approval, endorsement, sponsorship or recommendation by the AANS/CNS. The content should not be considered inclusive of all proper treatments, methods of care, or as statements of the standard of care and is not continually updated and may not reflect the most current evidence. -

Comparison Between Intermittent Mandatory Ventilation And

0021-7557/09/85-01/15 Jornal de Pediatria Copyright © 2009 by Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria ARTIGO ORIGINAL Comparison between intermittent mandatory ventilation and synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation with pressure support in children Comparação entre ventilação mandatória intermitente e ventilação mandatória intermitente sincronizada com pressão de suporte em crianças Marcos A. de Moraes1, Rossano C. Bonatto2, Mário F. Carpi2, Sandra M. Q. Ricchetti3, Carlos R. Padovani4, José R. Fioretto5 Resumo Abstract Objetivo: Comparar a ventilação mandatória intermitente (IMV) Objective: Tocompare intermittent mandatory ventilation (IMV) com a ventilação mandatória intermitente sincronizada com pressão with synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation plus pressure de suporte (SIMV+PS) quanto à duração da ventilação mecânica, support (SIMV+PS) in terms of time on mechanical ventilation, desmame e tempo de internação na unidade de terapia intensiva duration of weaning and length of stay in a pediatric intensive care pediátrica (UTIP). unit (PICU). Métodos: Estudo clínico randomizado que incluiu crianças entre Methods: This was a randomized clinical trial that enrolled 28 dias e 4 anos de idade, admitidas na UTIP no período children aged 28 days to 4 years who were admitted to a PICU correspondente entre 10/2005 e 06/2007, que receberam ventilação between October of 2005 and June of 2007 and put on mechanical mecânica (VM) por mais de 48 horas. Os pacientes foram alocados, ventilation (MV) for more than 48 hours. These patients were por meio de sorteio, em dois grupos: grupo IMV (GIMV;n=35)e allocated to one of two groups by drawing lots: IMV group (IMVG; n grupo SIMV+PS (GSIMV; n = 35). -

Tracheotomy in Ventilated Patients with COVID19

Tracheotomy in ventilated patients with COVID-19 Guidelines from the COVID-19 Tracheotomy Task Force, a Working Group of the Airway Safety Committee of the University of Pennsylvania Health System Tiffany N. Chao, MD1; Benjamin M. Braslow, MD2; Niels D. Martin, MD2; Ara A. Chalian, MD1; Joshua H. Atkins, MD PhD3; Andrew R. Haas, MD PhD4; Christopher H. Rassekh, MD1 1. Department of Otorhinolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia 2. Department of Surgery, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia 3. Department of Anesthesiology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia 4. Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Background The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) global pandemic is characterized by rapid respiratory decompensation and subsequent need for endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation in severe cases1,2. Approximately 3-17% of hospitalized patients require invasive mechanical ventilation3-6. Current recommendations advocate for early intubation, with many also advocating the avoidance of non-invasive positive pressure ventilation such as high-flow nasal cannula, BiPAP, and bag-masking as they increase the risk of transmission through generation of aerosols7-9. Purpose Here we seek to determine whether there is a subset of ventilated COVID-19 patients for which tracheotomy may be indicated, while considering patient prognosis and the risks of transmission. Recommendations may not be appropriate for every institution and may change as the current situation evolves. The goal of these guidelines is to highlight specific considerations for patients with COVID-19 on an individual and population level. Any airway procedure increases the risk of exposure and transmission from patient to provider. -

Methacholine Challenge Test 1 2

Methacholine Challenge Test 1 2 What is Methacholine Challenge Test (MCT)? Also, • Do not consume a heavy meal within 2 hours of the test. You can have a light It is a test that measures if your airways narrow after inhaling specific provoking meal e.g. sandwich, soup or salad within 2 hours before the test. agent. The provoking agent used in this test is inhaled methacholine. The degree • Do not wear any tight clothes. of resultant airway narrowing is dependent on each individual’s susceptibility and this airway narrowing will be assessed objectively by measuring the lung function You may also need to stop certain medications before taking the test depending on what clinical questions your physician would like answered based on your MCT changes before and after inhalation of the methacholine in progressively larger results. Different medications have to be stopped at different times before the test doses. Increased airway hyperresponsiveness is usually a hallmark feature of asthma. depending on how long they stay in your body. It is important for you to check with your doctor regarding the safety of stopping Why do I need this operation/procedure? these medications before discontinuing them for the test. Commonly, if you had presented with respiratory symptoms such as shortness of How long before the test? Avoid the following: breath, wheezing, chest tightness or cough, 6weeks Omalizumab your physician may consider doing a MCT to 1week Tiotropium (Spiriva) establish the diagnosis of asthma, especially if 48hours Combination inhalers such as Seretide (fluticasone/ initial lung function tests have not confirmed salmeterol) or Symbicort (budesonide/formoterol) or the diagnosis. -

Prevention of Ventilator Associated Complications

Prevention of Ventilator associated complications Authors: Dr Aparna Chandrasekaran* & Dr Ashok Deorari From: Department of Pediatrics , WHO CC AIIMS , New Delhi-110029 & * Neonatologist , Childs Trust Medical Research Foundation and Kanchi Kamakoti Childs Trust Hospital, Chennai -600034. Word count Text: 4890 (excluding tables and references) Figures: 1; Panels: 2 Key words: Ventilator associated complications, bronchopulmonary dysplasia Abbreviations: VAP- Ventilator associated pneumonia , BPD- Bronchopulmonary dysplasia, ELBW- Extremely low birth weight, VLBW- Very low birth weight, ROP- Retinopathy of prematurity, CPAP- Continuous positive airway pressure, I.M.- intramuscular, CI- Confidence intervals, PPROM- Preterm prelabour rupture of membranes, RCT- Randomised control trial, RR- Relative risk, PEEP- Peak end expiratory pressure Background: The last two decades have witnessed a dramatic reduction in neonatal mortality from 4.4 million newborn deaths annually in 1990 to 2.9 million deaths yearly in the year 2012, a reduction by 35%. In India, neonatal mortality has decreased by 42% during the same period. (1) With the increasing survival and therapeutic advances, the new paradigm is now on providing best quality of care and preventing complications related to therapy. Assisted ventilation dates back to 1879, when the Aerophone Pulmonaire, the world’s earliest ventilator was developed. This was essentially a simple tube connected to a rubber bulb. The tube was placed in the infant’s airway and the bulb was alternately compressed and released to produce inspiration and expiration. (2) With better understanding of pulmonary physiology and mechanics , lung protective strategies have evolved in the last two decades, with new resuscitation devices that limit pressure (T-piece resuscitator), non-invasive ventilation, microprocessors that allow synchronised breaths and regulate volume and high frequency oscillators/ jet ventilators. -

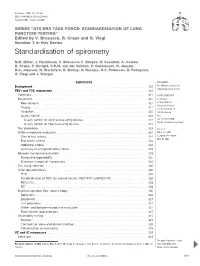

Standardisation of Spirometry

Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 319–338 DOI: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805 CopyrightßERS Journals Ltd 2005 SERIES ‘‘ATS/ERS TASK FORCE: STANDARDISATION OF LUNG FUNCTION TESTING’’ Edited by V. Brusasco, R. Crapo and G. Viegi Number 2 in this Series Standardisation of spirometry M.R. Miller, J. Hankinson, V. Brusasco, F. Burgos, R. Casaburi, A. Coates, R. Crapo, P. Enright, C.P.M. van der Grinten, P. Gustafsson, R. Jensen, D.C. Johnson, N. MacIntyre, R. McKay, D. Navajas, O.F. Pedersen, R. Pellegrino, G. Viegi and J. Wanger CONTENTS AFFILIATIONS Background ............................................................... 320 For affiliations, please see Acknowledgements section FEV1 and FVC manoeuvre .................................................... 321 Definitions . 321 CORRESPONDENCE Equipment . 321 V. Brusasco Requirements . 321 Internal Medicine University of Genoa Display . 321 V.le Benedetto XV, 6 Validation . 322 I-16132 Genova Quality control . 322 Italy Quality control for volume-measuring devices . 322 Fax: 39 103537690 E-mail: [email protected] Quality control for flow-measuring devices . 323 Test procedure . 323 Received: Within-manoeuvre evaluation . 324 March 23 2005 Start of test criteria. 324 Accepted after revision: April 05 2005 End of test criteria . 324 Additional criteria . 324 Summary of acceptable blow criteria . 325 Between-manoeuvre evaluation . 325 Manoeuvre repeatability . 325 Maximum number of manoeuvres . 326 Test result selection . 326 Other derived indices . 326 FEVt .................................................................. 326 Standardisation of FEV1 for expired volume, FEV1/FVC and FEV1/VC.................... 326 FEF25–75% .............................................................. 326 PEF.................................................................. 326 Maximal expiratory flow–volume loops . 326 Definitions. 326 Equipment . 327 Test procedure . 327 Within- and between-manoeuvre evaluation . 327 Flow–volume loop examples. 327 Reversibility testing . 327 Method .