May-Othmar H. Ammann.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helicopter Tours Views Winner in Style Best Nyc Tour With

NEW YORK CITY HUGE WINDOWS 180º TOUR HELICOPTER TOURS VIEWS WINNER IN STYLE BEST NYC TOUR WITH ASSOCIATION OF THE MOST ADVANCED HOTEL CONCIERGES HELICOPTERS IN N Y C SUBWAY DIRECTIONS OUR FLEET BELL 407 & 407GX AIRBUS EC130T2 Roomy, silent & Stadium seating, smooth ride with panoramic floor to ceiling windows & state- windows of-the-art, quiet technology 1 SOUTH FERRY, 2 3 WALL STREET N R WHITEHALL, 2 3 BOWING GREEN BUS: M1, M6 OR M15 TO SOUTH FERRY Hours: Monday - Saturday: 9am - 6pm 212.355.0801 WWW.HELINY.COM Downtown Manhattan Heliport, Pier 6, East River Email: [email protected] HELIPORT FEES $35 Heliport fee per passenger Prices & fees are subject to change without notice. Government issued photo ID required. Management reserves the right to refuse passengers. Flight times are approximate. Routes may vary depending on the weather and temporary flight restrictions. Management reserves the right to upgrade passengers. 212.355.0801 WINNER BEST NYC TOUR THE NEW YORKER THE ULTIMATE ASSOCIATION OF THE DELUXE VIP: AIR & SEA HOTEL CONCIERGES A fantastic bird’s-eye view of Our No. 1 ranked tour of NYC voted by An amazing 30 minute aerial excursion Experience NYC as a Jet-Setter with a New York City! the Association of Hotel Concierges in offering the best views of NYC VIP Helicopter & Boat Ride! 2008, 2009 & 2011 APPROX. 12 - 15 MINUTES APPROX. 25 - 30 MINUTES FLIGHT APPROX. 12 - 15 MINUTES APPROX. 17 - 20 MINUTES Experience the beauty The Deluxe tour includes all This special tour combines of the New York The Ultimate includes the sights included in our the celebrated NY Water Taxi Harbor, including an everything in the New Yorker Ultimate and New Yorker ‘Statue by Night’ cruise with up-close view of the tour. -

The Arch and Colonnade of the Manhattan Bridge Approach and the Proposed Designation of the Related Landmark Site (Item No

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 25, 1975, Number 3 LP-0899 THE ARCH AND COLONNAD E OF THE MANHATTAN BRIDGE APPROACH, Manhattan Bridge Plaza at Canal Street, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1912-15; architects Carr~re & Hastings. Landmark Site: Borough o£Manhattan Tax Map Block 290, Lot 1 in part consisting of the land on which the described improvement is situated. On September 23, 1975, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Arch and Colonnade of the Manhattan Bridge Approach and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No . 3). The hearing had been duly ad vertised in accordance with . the provisions of law. Two witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Manhattan Bridge Approach, a monumental gateway to the bridge, occupies a gently sloping elliptical plaza bounded by Canal, Forsyth and Bayard Streets and the Bowery. Originally designed to accommodate the flow of traffic, it employed traditional forms of arch and colonnade in a monument al Beaux-Arts style gateway. The triumphal arch was modeled after the 17th-century Porte St. Denis in Paris and the colonnade was inspired by Bernini's monumental colonnade enframing St. Peter's Square in Rome. Carr~re &Hastings, whose designs for monumental civic architecture include the New York Public Library and Grand Army Plaza, in Manhattan, were the architects of the approaches to the Manhattan Bridge and designed both its Brooklyn and Manhattan approaches. The design of the Manhattan Bridge , the the third bridge to cross the East River, aroused a good deal of controversy. -

It's the Way to Go at the Peace Bridge

The coupon is not an invoice. If you Step 3 Read the customer guide New Jersey Highway Authority Garden State Parkway are a credit card customer, you don’t carefully. It explains how to use E-ZPass have to worry about an interruption and everything else that you should know New Jersey Turnpike Authority New Jersey Turnpike in your E-ZPass service because we about your account. Mount your tag and New York State Bridge Authority make it easy for you by automatically you’re on your way! Rip Van Winkle Bridge replenishing your account when it hits Kingston-Rhinecliff Bridge a low threshold level. Mid-Hudson Bridge Newburgh-Beacon Bridge For current E-ZPass customers: Where it is available. Bear Mountain Bridge If you already have an E-ZPass tag from E-ZPass is accepted anywhere there is an E-ZPass logo. New York State Thruway Authority It’s the Way another toll agency such as the NYS This network of roads aids in making it a truly Entire New York State Thruway including: seamless, regional transportation solution. With one New Rochelle Barrier Thruway, you may use your tag at the account, E-ZPass customers may use all toll facilities Yonkers Barrier Peace Bridge in an E-ZPass lane. Any where E-ZPass is accepted. Tappan Zee Bridge to Go at the NYS Thruway questions regarding use of Note: Motorists with existing E-ZPass accounts do not Spring Valley (commercial vehicle only) have to open a new or separate account for use in Harriman Barrier your tag must be directed to the NYS different states. -

The Bayonne Bridge: Reconstruction of a 1931 Steel Arch

The Bayonne Bridge: Reconstruction of a 1931 Steel Arch Joseph LoBuono, PE (HDR/WSP) Engineering Symposium Rochester 2018 April 24, 2018 Project Development The Project Challenges Innovation Construction Status Project Development The Port of New York and New Jersey NEW JERSEY BAYONN E BRIDGE NEW YORK Bayonne Bridge History • Designed by Othmar Ammann and Cass Gilbert Also Designed The George Washington Bridge; Triborough Bridge; Bronx - Whitestone; Throgs Neck; and Verrazano- Narrows • Opened to Traffic on November 15, 1931 1,675-foot, Steel Arch Span was the Longest in the World at the Time, and Remained so for 46 years • 1985 Designated a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark • 2001 National and NJ State Historic Register Eligible (2003 NY Eligible) Existing Main Arch Span Problem: Bayonne Bridge Air Draft Restriction • Existing 151-foot Air Draft • The Expansion of the Panama Canal will Allow for New, Larger, (Post-Panamax) Ships with Increased Clearance Requirements 151 Feet • Taller Ships (up to 200-ft), will not be able to Navigate Beneath the Bayonne Bridge • The Bridge of the Americas (Pacific Approach to Panama Canal), has a 201-foot Clearance • Trends in Shipping (shown in photo) • 8,000 TEU Regina Maersk • 13,000 TEU Emma Maersk Problem: Bayonne Bridge Air Draft Restriction Raise the Roadway Rehabilitate, Retrofit, and Reuse - Arch Full Replacement of Approach Structures The Project Approach Structures: Articulation/Pier Fixity New York (12 spans, 272’ max, 125’ min) New Jersey (14 spans, 252’ max, 171’ min) Approach Structures: Piers Single Pier Combined Pier Tall Pier Main Span Roadway Looking North Existing & New Arch Floor System Challenges Challenges Upgrade 81 Year Old Structure to 2012 Code Cross-Sections: Arch Span – Original Design Cross-Section Comparison Wider Roadway 1930 Live Loading vs. -

Metuchen the Brainy Borough

METUCHEN THE BRAINY BOROUGH Compiled by the Metuchen Historic Preservation Committee Metuchen The Brainy Borough Compiled by the Metuchen historic preservation committee The Metuchen Historic Preservation Committee was formed in January 2008 to advise the Mayor and Council on steps to strengthen Metuchen’s commitment to historic preservation. The Committee’s goals are to develop public education on the benefits of historic preservation, honor Metuchen’s historic resources by increasing the number of structures in town listed on the New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places, and explore the development of a Metuchen Historic Preservation Ordinance to formally recognize and protect the town’s distinctive historic and architectural character. The Historic Preservation Committee Suzanne Andrews Lori Chambers Michele Clancy Richard Miller Tyreen Reuter, Chair Rebeccah Seely Richard Weber Nancy Zerbe Jay Muldoon, Council Liaison June, 2015. All Rights Reserved. Metuchen, New Jersey. Introduction For several years, the Metuchen Historic Preservation Committee — with the assistance of grants from the Middlesex County Cultural and Heritage Commission — has studied Metuchen’s history and historic neighborhoods to evaluate the potential for one or more historic districts. These studies have resulted in additional historical information, especially related to one important theme: Metuchen’s reputation as “the Brainy Borough.” Local historians were aware of the 1914-1915 newspaper “battle” between Metuchen and Glen Ridge as to which town deserved the title; however, there were no extant copies of the Metuchen Recorder newspaper that over the extended period of the battle carried each town’s submissions of prominent residents who would warrant their hometown being considered “brainy.” The Committee’s recent studies have not only added to the general knowledge of the battle; they resulted in a significant research find: much of Metuchen’s reporting on the subject was also reprinted in Bloomfield’s Independent Press,* available at the Bloomfield Public Library. -

Traffic Rules and Regulations/"Green Book" (PDF, 220

TRAFFIC RULES AND REGULATIONS For the Holland Tunnel Lincoln Tunnel George Washington Bridge Bayonne Bridge Goethals Bridge Outerbridge Crossing Revised September 2016 The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey is a self-supporting agency of the States of New York and New Jersey. It was created by a compact between the two States in 1921 for the development of transportation facilities and the promotion and protection of commerce in the New York/New Jersey metropolitan region. At the top of the organization is the twelve-member Board of Commissioners, appointed by the Governors of New York and New Jersey. There are six members from each state who serve for six-year overlapping terms. The Commissioners serve with-out pay as a public service. They report directly to the Governors of the two States, who have veto power over Commissioners’ actions. A career staff of more than 7,000 employees, headed by the Executive Director, is responsible to the Board of Commissioners. Over the years the Port Authority, at the direction of the States of New York and New Jersey has developed airports, marine terminals, bridges and tunnels, bus terminals, the PATH rapid transit system, the World Trade Center and other facilities of commerce and transportation. All of this has been accomplished without burden to the taxpayers. These undertakings are public projects; all are built with moneys borrowed solely on the Port Authority’s credit. There is no power to tax, or to pledge the credit of the States. i FOREWORD This booklet is intended to provide the users of Port Authority tunnels and bridges with detailed and specific information concerning rules, regulations and toll rates established by the Port Authority to regulate the conduct of traffic moving in or upon these vehicular crossings. -

Mr. Lincoln's Tunnel

PDHonline Course C750 (4 PDH) Mr. Lincoln’s Tunnel Instructor: J.M. Syken 2014 PDH Online | PDH Center 5272 Meadow Estates Drive Fairfax, VA 22030-6658 Phone & Fax: 703-988-0088 www.PDHonline.org www.PDHcenter.com An Approved Continuing Education Provider Mr. Lincoln’s Tunnel 1 Table of Contents Slide/s Part Description 1 N/A Title 2 N/A Table of Contents 3~19 1 Midtown-Hudson Tunnel 20-50 2 Weehawken or Bust 51~89 3 The Road More Traveled 90~128 4 On the Jersey Side 129~162 5 Similar, But Different 163~178 6 Third Tube 179~200 7 Planning for the Future 2 Part 1 Midtown-Hudson Tunnel 3 Namesake 4 In 1912, there were very few good roads in the United States. The relatively few miles of improved road were around towns and cities (a road was “improved” if it was graded). That year, Carl Fisher (developer of Miami Beach and the Indianapolis Speedway, among other things) conceived a trans-continental highway. He called it the “Coast-to-Coast Rock Highway.” It would be finished in time for the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition and would run from the exposition’s host city; San Francisco, to New York City. Two auto industry tycoons played major roles in the highway’s development: Frank Seiberling - president of Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., and Henry Joy - president of the Packard Motor Car Company. It was Henry Joy who came up with the idea of naming the highway after POTUS Abraham Lincoln. On July 1st 1913, the Lincoln Highway Association was officially incorporated. -

The Port Authority of NY & NJ

The Port Authority of NY & NJ 2012 to 2015 TOLL RATE TABLE George Washington Bridge, Lincoln Tunnel, Holland Tunnel, Goethals Bridge, Outerbridge Crossing, Bayonne Bridge PEAK HOURS: Weekdays 6 - 10 a.m., 4 - 8 p.m., Sat. & Sun. 11a.m. - 9 p.m. OFF-PEAK HOURS: All other times OVERNIGHT HOURS for Trucks: 10 p.m. - 6 a.m. Weekdays Beginning Dec. 2, 2012 Dec. 1, 2013 Dec. 7, 2014 Dec. 6, 2015 VEHICLE TYPE Trk Trk Trk Trk Off-Peak Peak Cash Off-Peak Peak Cash Off-Peak Peak Cash Off-Peak Peak Cash Overnight Overnight Overnight Overnight Class Vehicles with Two Axles and 1 $8.25 $10.25 N/A $13.00 $9.00 $11.00 N/A $13.00 $9.75 $11.75 N/A $14.00 $10.50 $12.50 N/A $15.00 Single Rear Wheels Vehicles with Two Axles and 2 $22.00 $24.00 $19.00 $30.00 $26.00 $28.00 $23.00 $34.00 $30.00 $32.00 $27.00 $38.00 $34.00 $36.00 $31.00 $42.00 Dual Rear Wheels** 3 Vehicles with Three Axles** $33.00 $36.00 $28.50 $45.00 $39.00 $42.00 $34.50 $51.00 $45.00 $48.00 $40.50 $57.00 $51.00 $54.00 $46.50 $63.00 4 Vehicles with Four Axles** $44.00 $48.00 $38.00 $60.00 $52.00 $56.00 $46.00 $68.00 $60.00 $64.00 $54.00 $76.00 $68.00 $72.00 $62.00 $84.00 5 Vehicles with Five Axles** $55.00 $60.00 $47.50 $75.00 $65.00 $70.00 $57.50 $85.00 $75.00 $80.00 $67.50 $95.00 $85.00 $90.00 $77.50 $105.00 Vehicles with Six Axles or 6 $66.00 $72.00 $57.00 $90.00 $78.00 $84.00 $69.00 $102.00 $90.00 $96.00 $81.00 $114.00 $102.00 $108.00 $93.00 $126.00 more** + Each add'l Axle $11.00 $12.00 $9.50 $15.00 $13.00 $14.00 $11.50 $17.00 $15.00 $16.00 $13.50 $19.00 $17.00 $18.00 $15.50 $21.00 Class -

The GREAT BRIDGE ARCHITECT/DESIGNER

1 The GREAT BRIDGE ARCHITECT/DESIGNER (Othmar Ammann left his Mark on New York City) Steve Krar Perhaps no twentieth-century engineer has left a more visible mark on a major city than had Othmar Ammann on New York. His five major bridges bear much of the enormous traffic flow to and from the city. They are beautiful and efficient structures, for Ammann achieved an uncommon harmony of visual elegance, simplicity, and power with practical design. Othmar Ammann Born in Switzerland, Othmar Ammann attended the Federal Polytechnic Institute of Zurich and earned an engineering degree in 1902. He had an interest in and an aptitude for mathematics and physics. Coming to the United States In August of 1907 the Quebec Bridge over the St. Lawrence River in Canada collapsed while under construction. Ammann offered to assist in the investigation of the collapse; his well-written report on the disaster earned him respect in his profession. The Hell Gate Bridge In 1912 Ammann was a chief assistant to Gustav Lindenthal, who was preparing for the great railroad bridge between Queens and Wards Island known as Hell Gate. The span was large; the ultimate design would be the longest arch-type bridge in the world. The rapid tidal currents made impossible to erect scaffolding in the river. The Hell Gate Bridge opened in 1917 and its design communicates rigidity with almost all its weight and outward thrust carried by the lower of the two steel arches. Hudson River Bridge Ammann’s final design for the Hudson River bridge called for a 3,500-foot span twice the length of any existing bridge, between Fort Lee in New Jersey and 179 Street in Manhattan. -

Bridges, Tunnels and Rail Advisory

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 25, 2020 Contact: The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey 212-435-7777 BRIDGES, TUNNELS AND RAIL ADVISORY Lane closings planned at the George Washington Bridge, Holland Tunnel and Outerbridge Crossing Face coverings required for anyone using Port Authority facilities to prevent spread of COVID-19 Lanes will be closed this week at the George Washington Bridge, Holland Tunnel and Outerbridge Crossing. As a reminder to the traveling public, face coverings are required for anyone using Port Authority facilities to help protect fellow passengers and employees from the spread of COVID- 19, including PATH trains and stations; the World Trade Center transportation hub; the Midtown Bus Terminal and George Washington Bridge Bus Station; the Port Authority’s airports and on AirTrain. Additionally, terminal access at John F. Kennedy, Newark Liberty and LaGuardia airports remains restricted to ticketed passengers, airport employees, and those who otherwise demonstrate a need to enter the facility for airport business. Travelers entering the region are also reminded that a tri-state travel advisory currently requires anyone entering New York, New Jersey and Connecticut from states with significant community spread of COVID-19 to quarantine for 14 days. Essential workers and travelers with layovers in the tri-state area are exempt. More information is available here for New York and New Jersey. George Washington Bridge: • From 10 p.m. Friday, Sept. 25, to 8 a.m. Saturday, Sept. 26, two westbound lanes on the upper level and the two westbound lanes of the upper level Trans-Manhattan Expressway will be closed. -

1 Interview with Princeton University Professor David Billington For

Interview with Princeton University Professor David Billington for Program Three: “Bridging New York” Note: This transcript is from a videotaped interview for the “Bridging New York” segment of “Great Projects.” It has been edited lightly for readability. David Billington (DB): It’s a curious fact that at least the three leading bridge designers in our tradition in America were immigrants from German-speaking countries: Roebling, John Roebling then, in 1831, Gustav Lindenthal, who came over in 1875, and Othmar Ammann in 1904. And a major reason for that, I think, is their educational system. The fact that, at least in Roebling’s case and in Ammann’s case, they were trained in the very best engineering schools at the time. Those schools also, particularly in Ammann’s case, emphasized strongly the study of completed structures rather than just merely the tools of analysis, as so often happens in engineering schools. And so when, during Ammann’s education his head was filled with images of all kinds of structures and, therefore, he came with a strong urge to design large-scale works. So did Roebling. DB: What they found when they came to this country, these immigrant engineers, in fact in a way what drew them to the country in the first place was the wide expanse of the country which meant the wide or the great possibilities in building. And in the sense of New York City, for example, this river, the Hudson River, which was an extraordinarily wide river close to a major city. So that this was a great challenge. -

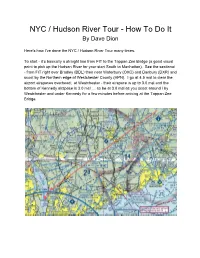

NYC / Hudson River Tour - How to Do It by Dave Dion

NYC / Hudson River Tour - How To Do It By Dave Dion Here’s how I’ve done the NYC / Hudson River Tour many times. To start - it’s basically a straight line from FIT to the Tappan Zee Bridge (a good visual point to pick up the Hudson River for your start South to Manhattan). See the sectional - from FIT right over Bradley (BDL) then near Waterbury (OXC) and Danbury (DXR) and scoot by the Northern edge of Westchester County (HPN). I go at 4.5 msl to clear the airport airspaces overhead; at Westchester - their airspace is up to 3.0 msl and the bottom of Kennedy airspace is 3.0 msl … so be at 3.0 msl as you scoot around / by Westchester and under Kennedy for a few minutes before arriving at the Tappan Zee Bridge. > BTW - I’ve flown all the way (to and from the Hudson) with flight following and WITHOUT flight following (talked to no one). You should flight follow and when asked about intentions or destination … say “Doing the Hudson River Exclusion today”. After starting with Bradley Approach (119.0) … a few handoffs to New York Approach and if they are having a good day … you’ll get a short cut through Westchester Airport (and they’ll assign an altitude through Kennedy Class B) to arrive the Hudson River South of the Tappan Zee Bridge Now it’s South to Manhattan on the West side of the Hudson (New Jersey side) - see kneeboard below for the following step by step references: > The following screenshots are the kneeboard available at faasafety.gov > Get set up (per the kneeboard) - basically 1.0 msl, a comfortable airspeed (e.g., less than 140; I do a little slow ~100 … with no flaps or flaps ..