In the Name of Security?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chad – Towards Democratisation Or Petro-Dictatorship?

DISCUSSION PAPER 29 Hans Eriksson and Björn Hagströmer CHAD – TOWARDS DEMOCRATISATION OR PETRO-DICTATORSHIP? Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, Uppsala 2005 Indexing terms Democratisation Petroleum extraction Governance Political development Economic and social development Chad The opinions expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Nordiska Afrikainstitutet Language checking: Elaine Almén ISSN 1104-8417 ISBN printed version 91-7106-549-0 ISBN electronic version 91-7106-550-4 © the authors and Nordiska Afrikainstitutet Printed in Sweden by Intellecta Docusys AB, Västra Frölunda 2005 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................5 2. Conceptual framework ...................................................................................7 2.1 Rebuilding state authorities, respect for state institutions and rule of law in collapsed states..................................................................7 2.2 Managing oil wealth for development and poverty reduction................11 2.3 External influence in natural resource rich states...................................19 3. State and politics in Africa: Chad’s democratisation process ..........................25 3.1 Historical background ..........................................................................25 3.2 Political development and democratisation...........................................26 3.3 Struggle for a real and lasting peace ......................................................37 -

"We Were Promised Development and All We Got Is Misery"

brief 41 “We were promised development and all we got is misery”— The Influence of Petroleum on Conflict Dynamics in Chad Contents List of Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 5 New oil fields in Chad 55 Executive Summary 7 5.1 Carte blanche for non compliance with Acknowledgments 7 environmental standards 56 Introduction 8 5.2 Opaque information policy 57 5.3 The social dimension 58 1 Conflict Background 10 1.1 A history of conflicts in Chad 11 Conclusion 64 1.2 The current conflict set-up 11 Annex: List of interviews 69 1.3 Peace attempts 17 References 71 2 Managing Oil Wealth 20 2.1 Effects of resource wealth in fragile states 21 2.2 The petro-state 22 2.3 The need for good governance 23 3 The Chad-Cameroon Oil Pipeline Project 24 3.1 Oil exploration and exploitation in southern Chad 25 3.2 The initial flow of oil money 26 3.3 Capacity-building 27 3.4 Oversight institutions 28 3.5 Inherent shortcomings 28 3.6 First changes in the model project 30 4 The Impact of Oil on Conflict Fatal Transactions is funded by the Dynamics 32 European Union. The content of this project is the sole responsibility of Fatal 4.1 The dimension of production site conflict Transactions and can in no way be taken to reflect dynamics 33 the views of the European Union. 4.2 Power stabilization through oil revenues 47 4.3 Oil for arms 53 Title citation: Villager from Béro brief 41 “We were promised development and all we got is misery”— The Influence of Petroleum on Conflict Dynamics in Chad Claudia Frank Lena Guesnet 3 List of Acronyms and Abbreviations AG Tschad Arbeitsgruppe -

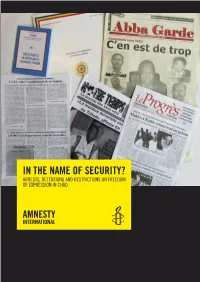

In the Name of Security?

IN THE NAME OF SECURITY? ARRests, detentiOns And RestRictiOns On FReedOm OF expRessiOn in chAd Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2013 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2013 Index: AFR 20/007/2013 English Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: A selection of Chadian publications related to arrests, detentions and attacks on freedom of expression. © Amnesty -

The World Bank and the Chad-Cameroon Oil Pipeline

Note Aligning Incentives for Development: The World Bank and the Chad-Cameroon Oil Pipeline Annalisa M. Leiboldt I. IN TRO D U CTION ................................................................................................................................. 167 II. THE CHAD-CAMEROON PIPELINE: THE WORLD BANK'S GREAT EXPERIMENT.............................170 A . Concession A greem ent ..................................................................................................... 170 B . W orld Bank Involvement .................................................................................................. 172 C. The Revenue Managem ent Law ........................................................................................ 174 D. Chad'sD isappointingPerformance................................................................................. 177 E. The Chad-Cameroon Oil Pipeline Today.........................................................................178 1. R evenue M anagement........................................................................................... 178 2. Compensationfor Affected Communities.............................................................179 3 . Loca l Jobs ............................................................................................................. 181 4. Environmental Impacts.........................................................................................1 82 1II. MISALIGNED INCENTIVES: A ROLE FOR THE WORLD BANK.........................................................183 -

2008 Human Rights Report: Chad 2008 Human Rights Report: Chad

2008 Human Rights Report: Chad 2008 Human Rights Report: Chad Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor 2008 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices February 25, 2009 Chad is a centralized republic with a population of approximately 10 million. In 2006 citizens reelected President Idriss Deby, leader of the Patriotic Salvation Movement (MPS), to a third term in what unofficial observers characterized as an orderly but seriously flawed election boycotted by the opposition. Deby has ruled the country since taking power in a 1990 coup. Political power remained concentrated in the hands of a northern oligarchy composed of the president's Zaghawa ethnic group and its allies. The executive branch dominated the legislature and judiciary. Despite 2006 and 2007 peace accords with rebel groups, fighting between the government and rebels continued and resulted in civilian deaths and the widespread destruction of homes and property during the year. Rebels attacked N'Djamena in February, as well as locations in the east in June. The government supported Sudanese rebels. Violent interethnic conflict, banditry, and cross-border raids by Darfur-based militias continued. Civilians were killed, and an estimated 185,000 have been internally displaced as a result of violence. Approximately 250,000 Sudanese refugees who had fled from violence in Darfur lived in camps along the border.On March 15,the European Union Force (EUFOR) in Chad, whose mandate includes protecting civilians, including internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees, and facilitating the delivery of humanitarian assistance in the east, reached operational capacity.Civilian authorities did not maintain effective control of the security forces. -

Writenet Chad: Politics and Security

writenet is a network of researchers and WRITENET writers on human rights, forced migration, ethnic and political conflict independent writenet is the resource base of practical management (UK) CHAD: POLITICS AND SECURITY A Writenet Report by Roy May and Simon Massey March 2007 Caveat: Writenet papers are prepared mainly on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. The papers are not, and do not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. The views expressed in the paper are those of the author and are not necessarily those of Writenet. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms ................................................................................................... i Executive Summary ................................................................................. ii 1 Introduction........................................................................................1 2 The Context of the Political/Security Nexus....................................3 2.1 Political, Social and Economic Background to the Current Conflict .....3 2.2 Constitutional Amendment and the 2006 Presidential Election..............5 3 Internal and External Actors............................................................6 3.1 The Registered Opposition..........................................................................6 3.2 Politico-military Factions ............................................................................7 -

Resolving the Chadian Political Epilepsy: an Assessment of Intervention Efforts

Institute for Security Studies Situation Report Date issued: 1 June 2009 Author: Chrysantus Ayangafac1 Distribution: General Contact: [email protected] Resolving the Chadian Political Epilepsy: An Assessment of Intervention Efforts Chad’s political economy is littered with the wreckage of failed attempts at Introduction resolving the country’s intractable political crisis. Since independence, Chad has not witnessed any constitutional transfer of power. Its political history is a story of drawn-out conflicts with incidental cessation of hostilities, peace agreements and national elections.2 In reality, these events have merely provided an opportunity for alignment, realignment and, in the process, preparation for the next battle. The attack on N’Djamena in February 2008 might not be the last of these.3 As Chad’s belligerents flex their muscle for yet another round of a violent contest for the soul of the Chadian state, the stage seems set for renewed violence. Hopefully they are grandstanding for potential negotiation. Against this backdrop, it is imperative to interrogate whether the international community so far has been right about Chad, and, if not, why and what could be done to improve the situation? Considering the present international response to the crisis, is there any political incentive for President Déby’s regime to accommodate a robust political solution that will usher in peace; is the regime prepared to pay the political cost of peace – at least from a human security perspective? This situation report analyses and presents an update on the domestic and international responses to the Chadian crisis. It concludes that though the current policy approach is certainly not a panacea to the Chadian crisis, it is a good starting point. -

2016 Country Review

Chad 2016 Country Review http://www.countrywatch.com Table of Contents Chapter 1 1 Country Overview 1 Country Overview 2 Key Data 3 Chad 4 Africa 5 Chapter 2 7 Political Overview 7 History 8 Political Conditions 14 Political Risk Index 41 Political Stability 55 Freedom Rankings 71 Human Rights 82 Government Functions 86 Government Structure 88 Principal Government Officials 91 Leader Biography 93 Leader Biography 93 Foreign Relations 94 National Security 109 Defense Forces 116 Chapter 3 118 Economic Overview 118 Economic Overview 119 Nominal GDP and Components 121 Population and GDP Per Capita 123 Real GDP and Inflation 124 Government Spending and Taxation 125 Money Supply, Interest Rates and Unemployment 126 Foreign Trade and the Exchange Rate 127 Data in US Dollars 128 Energy Consumption and Production Standard Units 129 Energy Consumption and Production QUADS 130 World Energy Price Summary 131 CO2 Emissions 132 Agriculture Consumption and Production 133 World Agriculture Pricing Summary 135 Metals Consumption and Production 136 World Metals Pricing Summary 138 Economic Performance Index 139 Chapter 4 151 Investment Overview 151 Foreign Investment Climate 152 Foreign Investment Index 154 Corruption Perceptions Index 167 Competitiveness Ranking 178 Taxation 187 Stock Market 188 Partner Links 188 Chapter 5 189 Social Overview 189 People 190 Human Development Index 192 Life Satisfaction Index 196 Happy Planet Index 207 Status of Women 216 Global Gender Gap Index 219 Culture and Arts 228 Etiquette 228 Travel Information 229 Diseases/Health -

BTI 2018 Country Report Chad

BTI 2018 Country Report Chad This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2018. It covers the period from February 1, 2015 to January 31, 2017. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2018 Country Report — Chad. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2018 | Chad 3 Key Indicators Population M 14.5 HDI 0.396 GDP p.c., PPP $ 1991 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 3.1 HDI rank of 188 186 Gini Index 43.3 Life expectancy years 52.6 UN Education Index 0.308 Poverty3 % 66.5 Urban population % 22.6 Gender inequality2 0.695 Aid per capita $ 43.3 Sources (as of October 2017): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2017 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2016. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary The period under review was mainly dominated by three issues: the presidential election, social and economic crisis, and the terrorist threat posed by Boko Haram. -

The Inspection Panel

The Inspection Panel Report and Recommendation Public Disclosure Authorized on Request for Inspection Chad: Petroleum Development and Pipeline Project (Loan No. 4558-CD); Management of the Petroleum Economy Project (Credit No. 3316-CD); Petroleum Sector Management Capacity-Building Project (Credit No. 3373-CD) Public Disclosure Authorized 1. On March 22, 2001, the Inspection Panel (the “Panel”) received a Request for Inspection (the “Request”) related to the above-referenced Projects (hereinafter referred to as the Projects). (Annex 1). On April 11, 2001 the Panel notified the representative of the Requesters, the Executive Directors and the Bank President of the registration of the Request.1 On June 7, 2001, in the light of the electoral and post- electoral process in Chad, the Panel proposed to the Executive Directors to delay the issuance of this eligibility report for a period of about ninety days. On June 19, 2001 the Executive Directors recorded their approval to such proposal, allowing the Panel to delay this report until September 17, 2001. Public Disclosure Authorized A. FINANCIAL ARRANGEMENTS 2. The Request makes reference to issues related to three closely related Bank-supported Projects in Chad. 2 These Projects and related financial arrangements are:3 (a) The Petroleum Development and Pipeline Project (hereinafter referred to as the “Pipeline Project” or the “Project”), approved on June 6, 2000, is financed by both the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) under a loan in an amount equal to US$39.5 million,4 and the 1 See The Inspection Panel, Operating Procedures (August 1994), at § 17. 2 This Report covers only allegations pertaining to the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and the International Development Association (IDA). -

Inlaga DP 29

DISCUSSION PAPER 29 Hans Eriksson and Björn Hagströmer CHAD – TOWARDS DEMOCRATISATION OR PETRO-DICTATORSHIP? Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, Uppsala 2005 Indexing terms Democratisation Petroleum extraction Governance Political development Economic and social development Chad The opinions expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Nordiska Afrikainstitutet Language checking: Elaine Almén ISSN 1104-8417 ISBN printed version 91-7106-549-0 ISBN electronic version 91-7106-550-4 © the authors and Nordiska Afrikainstitutet Printed in Sweden by Intellecta Docusys AB, Västra Frölunda 2005 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................5 2. Conceptual framework ...................................................................................7 2.1 Rebuilding state authorities, respect for state institutions and rule of law in collapsed states..................................................................7 2.2 Managing oil wealth for development and poverty reduction................11 2.3 External influence in natural resource rich states...................................19 3. State and politics in Africa: Chad’s democratisation process ..........................25 3.1 Historical background ..........................................................................25 3.2 Political development and democratisation...........................................26 3.3 Struggle for a real and lasting peace ......................................................37 -

No. 10 HELGA DICKOW

Lettres de Byblos Letters from Byblos No. 10 HELGA DICKOW In collaboration with Petra Bauerle Democrats without Democracy? Attitudes and opinions on society, religion and politics in Chad Centre International des Sciences de l'Homme International Centre for Human Sciences Byblos 2005 Lettres de Byblos Letters from Byblos No. 10 HELGA DICKOW In collaboration with Petra Bauerle Translated by John Richardson Democrats without Democracy? Attitudes and opinions on society, reli gion and politics in Chad Centre International des Sciences de l'Homme International Centre for Human Sciences Byblos 2005 Lettres de Byblos / Letters from Byblos A series of occasional papers published by UNESCOCentre International des Sciences de l’Homme International Centre for Human Sciences (Arabic) The opinions expressed in this monograph are those of the author and should not be construed as representing those of the International Centre for Human Sciences. All rights reserved. Printed in Lebanon. No part of this publication may be re- produced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechani- cal, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. C International Centre for Human Sciences, 2005 Published in 2005 in Lebanon by the International Centre for Human Sciences, B.P. 225 Byblos (Jbeil), Liban. ISBN 9953-0-0575-3 In memory of my father, Heinz Dickow (1913–2004) Acknowledgements This study on Chad was undertaken at the suggestion of Professor Theodor Hanf, director of the Arnold Bergstraesser Institute, Freiburg, Germany, and the Centre International des Science de l'Homme, Byblos, Lebanon. I take this opportunity to ex- press my deep gratitude for his support.