To Equal Citizens: Political And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nepali Times Drop to the Floor Mauritius, Dominica, Sao Tome and State Divide and Encompassing Canada

#221 12 - 18 November 2004 20 pages Rs 25 Weekly Internet Poll # 161 Q. Should the pre-2002 parliament be reinstated? The peace industry Is there a conflict of interest in the peace efforts? Total votes:1,002 NAVIN SINGH KHADKA officials told us the money was foundation for future peace Weekly Internet Poll # 162. To vote go to: www.nepalitimes.com used for capacity building in process. Government officials Q. Do you agree with the proposal for a special he more elusive peace conflict resolution for officials, quota for disadvantaged groups in education? are not comfortable about the T becomes, the more it parliamentarians and civil formation of the Citizens Peace seems to become an society, research and conflict Commission, an umbrella industry. Foreign conflict- analysis and support for media. organisation of peace groups. Mohsinisms resolution consultants and Visiting British Minister of Why do you need a parallel Interview with Minister of mediation experts are State Douglas Alexander, said in organisation when a Peace Information, Mohammad Mohsin swarming all over the capital, Kathmandu Wednesday: Nepals Secretariat has already been Is the peace secretariat just an sometimes rubbing shoulders problem should be resolved formed? asked one member of eyewash? in hotel lobbies with arms internally, and we will support the High-Level Peace It will take time for the secretariat merchants. such efforts. Committee. to become fully operational. We At last count there were at The Europeans hired two Most people interviewed for are collecting documents for a least two dozen government experts to prepare a report on this article agreed the peace archive. -

House of Lords Official Report

Vol. 759 Tuesday No. 106 24 February 2015 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) HOUSE OF LORDS OFFICIAL REPORT ORDER OF BUSINESS Questions National Curriculum: Animal Welfare .............................................................................................................1529 Gurkhas ................................................................................................................................................................1531 Yarl’s Wood .........................................................................................................................................................1533 Armed Forces: Baltic Defence ..........................................................................................................................1536 Specialist Printing Equipment and Materials (Offences) Bill Order of Commitment Discharged .....................................................................................................................1538 Consumer Rights Bill Commons Reason .................................................................................................................................................1539 Human Fertilisation and Embryology (Mitochondrial Donation) Regulations 2015 Motion to Approve..............................................................................................................................................1569 Gambling: Fixed-odds Betting Machines Question for Short Debate.................................................................................................................................1627 -

The Gurkhas', 1857-2009

"Bravest of the Brave": The making and re-making of 'the Gurkhas', 1857-2009 Gavin Rand University of Greenwich Thanks: Matthew, audience… Many of you, I am sure, will be familiar with the image of the ‘martial Gurkha’. The image dates from nineteenth century India, and though the suggestion that the Nepalese are inherently martial appears dubious, images of ‘warlike Gurkhas’ continue to circulate in contemporary discourse. Only last week, Dipprasad Pun, of the Royal Gurkha Rifles, was awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Cross for single-handedly fighting off up to 30 Taliban insurgents. In 2010, reports surfaced that an (unnamed) Gurkha had been reprimanded for using his ‘traditional’ kukri knife to behead a Taliban insurgent, an act which prompted the Daily Mail to exclaim ‘Thank god they’re on our side!) Thus, the bravery and the brutality of the Gurkhas – two staple elements of nineteenth century representations – continue to be replayed. Such images have also been mobilised in other contexts. On 4 November 2008, Chief Superintendent Kevin Hurley, of the Metropolitan Police, told the Commons’ Home Affairs Select Committee, that Gurkhas would make excellent ‘recruits’ to the capital’s police service. Describing the British Army’s Nepalese veterans as loyal, disciplined, hardworking and brave, Hurley reported that the Met’s senior commanders believed that ex-Gurkhas could provide a valuable resource to London’s police. Many Gurkhas, it was noted, were multilingual (in subcontinental languages, useful for policing the capital’s diverse population), fearless (and therefore unlikely to be intimidated by the apparently rising tide of knife and gun crime) and, Hurley noted, the recruiting of these ‘loyal’, ‘brave’ and ‘disciplined’ Nepalese would also provide an excellent (and, one is tempted to add, convenient) means of diversifying the workforce. -

Land Politics in Nepal: an Ethnographic Study of Makar VDC in Nawalparasi District

Land Politics in Nepal: An Ethnographic Study of Makar VDC in Nawalparasi District The Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Humanities and Social Science in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Master in Anthropology By Dilli Ram Timilsina Tribhuvan University Central Department of Sociology/Anthropology Kirtipur, Kathmandu 2008 Faculties of Humanities and Social Science Central Department of Sociology/Anthropology Recommendation Letter This dissertation entitled “Land Politics in Nepal: An Ethnographic Study of Makar VDC in Nawalparasi District” prepared by Dilli Ram Timilsina under the supervision and guidance for the partial fulfillment of Master Degree in Anthropology. The study is original and carries useful information in the field of land. Therefore, I recommend it for the evaluation to the dissertation committee. ________________________ Dr. Saubhagya Shah Associate Professor Central Department of Sociology/Anthropology T.U. Kritipur Tribhuvan University Faculties of Humanities and Social Science Central Department of Sociology/Anthropology This thesis titled “Land Politics in Nepal: An Ethnographic Study of Makar VDC in Nawalparasi District” submitted to the Central Department of Sociology/Anthropology Tribhuvan University by Dilli Ram Timilsina has been approved by the undersigned members of the Research Committee. Members of the Research Committee: _____________________ __________________ Internal Examiner Dr. Saubhagya Shah _____________________ __________________ External Examiner _______________________ __________________ Head Dr. Om Gurung Central Department of Sociology/Anthropology T.U. Kirtipur Date: -------------------------------- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Researching and writing this dissertation has been much like a journey for me. And like many journeys it is one in which numerous people have helped me along the way. My greatest debt is to the people of Makar VDC whose voices and responses resound within the research. -

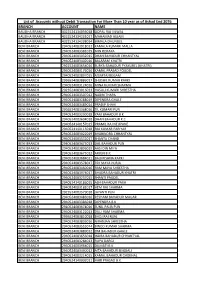

Branch Account Name

List of Accounts without Debit Transaction For More Than 10 year as of Ashad End 2076 BRANCH ACCOUNT NAME BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134056018 GOPAL RAJ SILWAL BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134231017 MAHAMAD ASLAM BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134298014 BIMALA DHUNGEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083918012 KAMALA KUMARI MALLA BENI BRANCH 2940524083381019 MIN ROKAYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083932015 DHAN BAHADUR CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083402016 BALARAM KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2922524083654016 SURYA BAHADUR PYAKUREL (KHATRI) BENI BRANCH 2940524083176016 KAMAL PRASAD POUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083897015 MUMTAJ BEGAM BENI BRANCH 2936524083886017 SHUSHIL KUMAR KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083124016 MINA KUMARI SHARMA BENI BRANCH 2923524083016013 HASULI KUMARI SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083507012 NABIN THAPA BENI BRANCH 2940524083288019 DIPENDRA GHALE BENI BRANCH 2940524083489014 PRADIP SHAHI BENI BRANCH 2936524083368016 TIL KUMARI PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083230018 YAM BAHADUR B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083604018 DHAN BAHADUR K.C BENI BRANCH 2940524140157015 PRAMIL RAJ NEUPANE BENI BRANCH 2940524140115018 RAJ KUMAR PARIYAR BENI BRANCH 2940524083022019 BHABINDRA CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083532017 SHANTA CHAND BENI BRANCH 2940524083475013 DAL BAHADUR PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083896019 AASI DIN MIYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083675012 ARJUN B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083684011 BALKRISHNA KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083578017 TEK MAYA PURJA BENI BRANCH 2940524083460016 RAM MAYA SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083974017 BHADRA BAHADUR KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2940524083237015 SHANTI PAUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524140186015 -

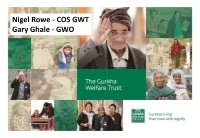

Nigel Rowe - COS GWT Gary Ghale - GWO

Nigel Rowe - COS GWT Gary Ghale - GWO Registered Charity No. 1103669 Enduring Tenets Vision: Gurkhas living their lives in dignity. Mission Statement: The Gurkha Welfare Trust aims to provide welfare to enable Gurkha ex- servicemen, their dependants and their communities to live their lives with dignity, primarily in Nepal but increasingly in UK and elsewhere. Registered Charity No. 1103669 What we do Individual Aid: • Welfare Pensions • Welfare/Disability Grants • Residential Homes • Medical Scheme Community Aid: • Water (RWSP) • Schools • Community Centres/Medical Posts Registered Charity No. 1103669 Area Welfare Centres Registered Charity No. 1103669 The Gurkha Welfare Scheme Area Welfare Centre (AWC) and Patrol Base locations AWCs (East) Code AWC 13 Bagmati 14. Jiri 15 Rumjatar 16 Diktel India 18 Bhojpur 19 Khandbari 20 Tehrathum China 21 Taplejung 1 22 Phidim 23 Dharan 5 AWCs (West) 4 24 Darjeeling 1 6 Code AWC 7 25 Damak 2 9 5 1 Bheri 3 10 8 3 3 Gulmi 14 12 11 4. Beni 13 7 6 Kaski 19 21 In dia 15 7 Lamjung 16 24 18 20 22 8 8 Gorkha India 10 6 9 Syangja 23 25 9 10 Tanahun 11 Chitwan Patrol Base (East) 12 Butwal Patrol Bases (West) 5. Trisuli (through AWC Bagmati) 1. Kohalpur (through AWC Bheri) 6. Katari (through AWC Dharan) 2. Ghorahi (through AWC Butwal) 7. Solu Salleri (through AWC Rumjatar) 3. Bhalubang (through AWC Butwal) 8. Kurseong (through AWC Darjeeling) 5. Tansen (through AWC Butwal) 9. Siliguri (through AWC Darjeeling) 10. Kalimpong (through AWC Darjeeling) Registered Charity No. 1103669 TRUST ACTIVITIES – Welfare Pensioners Registered Charity No. -

Considering Dalits and Political Identity In

#$%&'#(')$#*%+,'-.+%/0$'$1.$,1/)'2,/3*%4/1& )+,4/0*%/,5'0$./14'$,0' 6+./1/)$.'/0*,1/1&'/,'/#$5/,/,5' $',*7',*6$. In this article I examine the articulation between contexts of agency within two kinds of discur- sive projects involving Dalit identity and caste relations in Nepal, so as to illuminate competing and complimentary forms of self and group identity that emerge from demarcating social perim- eters with political and economic consequences. The first involves a provocative border created around groups of people called Dalit by activists negotiating the symbols of identity politics in the country’s post-revolution democracy. Here subjective agency is expressed as political identity with attendant desires for social equality and power-sharing. The second context of Dalit agency emerges between people and groups as they engage in inter caste economic exchanges called riti maagnay in mixed caste communities that subsist on interdependent farming and artisan activi- ties. Here caste distinctions are evoked through performed communicative agency that both resists domination and affirms status difference. Through this examination we find the rural terrain that is home to landless and poor rural Dalits only partially mirrors that evoked by Dalit activists as they struggle to craft modern identities. The sources of data analyzed include ethnographic field research conducted during various periods from 1988-2005, and discussions that transpired through- out 2007 among Dalit activist members of an internet discussion group called nepaldalitinfo. -

Identity-Based Conflict and the Role of Print Media in the Pahadi Community of Contemporary Nepal Sunil Kumar Pokhrel Kennesaw State University

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects 7-2015 Identity-Based Conflict and the Role of Print Media in the Pahadi Community of Contemporary Nepal Sunil Kumar Pokhrel Kennesaw State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/etd Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Pokhrel, Sunil Kumar, "Identity-Based Conflict and the Role of Print Media in the Pahadi Community of Contemporary Nepal" (2015). Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects. Paper 673. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IDENTITY-BASED CONFLICT AND PRINT MEDIA IDENTITY-BASED CONFLICT AND THE ROLE OF PRINT MEDIA IN THE PAHADI COMMUNITY OF CONTEMPORARY NEPAL by SUNIL KUMAR POKHREL A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Conflict Management in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, Georgia March 2015 IDENTITY-BASED CONFLICT AND PRINT MEDIA © 2015 Sunil Kumar Pokhrel ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Recommended Citation Pokhrel, S. K. (2015). Identity-based conflict and the role of print media in the Pahadi community of contemporary Nepal. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, Georgia, United States of America. IDENTITY-BASED CONFLICT AND PRINT MEDIA DEDICATION My mother and father, who encouraged me toward higher study, My wife, who always supported me in all difficult circumstances, and My sons, who trusted me during my PhD studies. -

Locating Nepalese Mobility: a Historical Reappraisal with Reference to North East India, Burma and Tibet Gaurab KC* & Pranab Kharel**

Volume 6 Issue 2 November 2018 Kathmandu School of Law Review Locating Nepalese Mobility: A Historical Reappraisal with Reference to North East India, Burma and Tibet Gaurab KC* & Pranab Kharel** Abstract Most literature published on migration in Nepal makes the point of reference from 19th century by stressing the Lahure culture—confining the trend’s history centering itself on the 200 years of Nepali men serving in British imperial army. However, the larger story of those non-military and non-janajati (ethnic) Nepali pilgrimages, pastoralists, cultivators and tradesmen who domiciled themselves in Burma, North East India and Tibet has not been well documented in the mobility studies and is least entertained in the popular imagination. Therefore, this paper attempts to catalog this often neglected outmigration trajectory of Nepalis. Migrants venturing into Burma and North East India consist of an inclusive nature as the imperial army saw the overwhelming presence of hill janajatis in their ranks whereas Brahmins (popularly known as Bahuns) and Chettris were largely self-employed in dairy farming and animal husbandry. In tracing out the mobility of Nepalis to North East, Burma and Tibet it can be argued that the migrating population took various forms such as wanderers (later they became settlers), mercantilist, laborers, mercenary soldiers, and those settlers finally forced to become returnees. In this connection, documenting lived experiences of the living members or their ancestors is of paramount importance before the memory crosses the Rubicon. Introduction: In the contemporary Nepali landscape, the issue of migration has raised new interests for multiple actors like academicians, administrators, activists, development organizations, planners, policymakers, and students. -

Caste, Military, Migration: Nepali Gurkha Communities in Britain

Article Ethnicities 2020, Vol. 20(3) 608–627 Caste, military, migration: ! The Author(s) 2019 Nepali Gurkha communities Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions in Britain DOI: 10.1177/1468796819890138 journals.sagepub.com/home/etn Mitra Pariyar Kingston University, UK Oxford University, UK Abstract The 200-year history of Gurkha service notwithstanding, Gurkha soldiers were forced to retire in their own country. The policy changes of 2004 and 2009 ended the age-old practice and paved the way for tens of thousands of retired soldiers and their depend- ants to migrate to the UK, many settling in the garrison towns of southern England. One of the fundamental changes to the Nepali diaspora in Britain since the mass arrival of these military migrants has been the extraordinary rise of caste associations, so much so that caste – ethnicised caste –has become a key marker of overseas Gurkha community and identity. This article seeks to understand the extent to which the policies and practices of the Brigade of Gurkhas, including pro-caste recruitment and organisation, have contributed to the rapid reproduction of caste abroad. Informed by Vron Ware’s paradigm of military migration and multiculture, I demonstrate how caste has both strengthened the traditional social bonds and exacerbated inter-group intol- erance and discrimination, particularly against the lower castes or Dalits. Using the military lens, my ethnographic and historic analysis adds a new dimension to the largely hidden but controversial problem of caste in the UK and beyond. Keywords Gurkha Army, Gurkha migration to UK, caste and militarism, Britain, overseas caste, Nepali diaspora in England Corresponding author: Mitra Pariyar, Kingston University, Penrhyn Road, Kingston-Upon-Thames KT1 2EE, UK. -

The Biography of a Magar Communist Anne De Sales

The Biography of a Magar Communist Anne de Sales To cite this version: Anne de Sales. The Biography of a Magar Communist. David Gellner. Varieties of Activist Ex- periences in South Asia, Sage, pp.18-45, 2010, Governance, Conflict, and Civic Action Series. hal- 00794601 HAL Id: hal-00794601 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00794601 Submitted on 10 Mar 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Chapter 2 The Biography of a Magar Communist Anne de Sales Let us begin with the end of the story: Barman Budha Magar was elected a Member of Parliament in 1991, one year after the People’s Movement (jan andolan) that put an end to thirty years of the Partyless Panchayat ‘democracy’ in Nepal. He had stood for the Samyukta Jana Morcha or United People’s Front (UPF), the political wing of the revolutionary faction of the Communist Party of Nepal, or CPN (Unity Centre).1 To the surprise of the nation, the UPF won 9 seats and the status of third-largest party with more than 3 per cent of the national vote. However, following the directives of his party,2 Barman, despite being an MP, soon went underground until he retired from political life at the time of the People’s War in 1996. -

The Kham Magar Country, Nepal: Between Ethnic Claims and Maoism Anne De Sales (Translated by David N

41 The Kham Magar country, Nepal: Between ethnic claims and Maoism Anne de Sales (translated by David N. Gellner) Identity politics were unheard of in the early 1980s, when I carried out my first fieldwork among the Kham Magar, a Tibeto-Burman population of west Nepal. If people felt like comparing or defining themselves, they focused on very local dif- ferences: on the dialects of different villages, their specific festival calendars, their different ways of covering haystacks (by means of a cover made of goatskin or with a straw roof), the different itineraries they followed with their flocks, or the boundaries of their communal territories. Subjects like these were discussed again and again. Such conversations presupposed a common shared identity, of course, but there was no context in which Kham Magars needed to articulate it. For exam- ple, relations with their cousins, the Magar, the largest minority in Nepal, were undefined and the exploration of differences between Kham Magars and Magars did not appear to be important, at least to the Kham Magar themselves. In sum, Kham Magar villagers preferred to see themselves and to be seen as the inhabitants of one ‘country’, deß in Nepali (the term has been adopted into the Kham Magars’ Tibeto-Burman language). A ‘country’ is a given natural environment in which one is born and where one lives alongside others similar to oneself. It is the Kham Magars’ ‘country’ that has turned out to be the stronghold of the ‘People’s War’ launched four years ago by the revolutionary Maoist movement. The life of the Kham Magar has been turned upside-down by this, and many of them have died.