Appendix to Petition for a Writ of Certiorari ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

64 Matters of Interest Their Work with Enthusiasm and Took Pride in It~ Quality. I Feel, Therefore, That 1 Must Share Y~Mr Kind Congratulations Witp Them

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-97-01-10 on 1 July 1951. Downloaded from 64 Matters of Interest their work with enthusiasm and took pride in it~ quality. I feel, therefore, that 1 must share y~mr kind congratulations witp them. This is especially so in the case of Major Frank Ship, who was my Deputy at that time, and who is now an Orthopcedic Surgeon in the Leahy Clinic in Boston. _ A few years ago I entered political life. I represent Regina City in the Federal House and am now Parliamentary Assistant to the Hon. Paul Martin, Minister of National Health and Welfare, a position which I find very interesting. Thanking you once more for your kind reference to my work. Sincerely, E. A. MCCUSKER, M.P ... ' Parliamentary Assistant . • Matters of Interest guest. Protected by copyright. HONOURS AND AWARDS WE read with particular pleasure of recent honours bestowed on officers of the Medical Services. Captain C. W. Bowen, RA.M.C., RM.O. to the 1st Battalion the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers, has been awarded the Military Cross for gallantry in action in Korea. Captain Bowen is a recalled reservist. In the Order of St. John of Jerusalem. Major-General F. Harris, C.B., C.B.E., M.C., M.B., K.H.S., late RA.M.C., Major-General W. E. Tyndall, c.B., C.B.E., M.C., M.B., D.P.H., late RA.M.C., and Brigadier Dame Anne Thomson, D.B.E., RR.C" K.H.N.S., Q.A.RA.N.C., have been appointed Officers and Major S. -

Representatives of William H. Freeman

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 4-18-1848 Representatives of William H. Freeman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation H.R. Rep. No. 476, 30th Cong., 1st Sess. (1848) This House Report is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I THIRTIETH CONGRESS-FIRST SE SION. Report No. 476. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. REPRESENTATIVES OF WILLIAM H. FREEMAN. APRIL 18, 1848. Laid upon the table. Mr. JoHN A. RocKWELL, from the Committee of -Claims, made the following REPORT: The Corn:mittee of Claims, to wliom was referred the petition of the legal representatives of William lf. Freeman, report as follows: The subject matter of this claim has been twice submitted to ju d i cial investigation, and in both cases the decision on the ques tions involved have· been against the claim of the petitioners upori the points of law in the case. The first decision was made by the Supreme Court of the United States, as will appear by reference to t he case, reported in the third volume of Howard's Reports. -

Colonel Commandant Honour Board

Royal Regiment of Australian Artillery Honorary Appointments Colonels Commandant Establishment The Honorary Colonel concept was ad hoc until 1955 when a Colonel Commandant was appointed in each State. This was promulgated as follows: “The Military Board has considered the scale of appointment, duties and privileges of Honorary Colonels / Colonels Commandant. Military Board Instruction 186 dated 28 Sep 56 on this subject has been issued.” Review and Revised Structure During 2016 - 2019 the RCC and HOR implemented a review of the role and support provided by the long-standing existing Colonels Commandant structure. The outcome saw a move away from geographically state based appointments and the adoption of a dedicated Colonel Command for each RAA Regiment. One of these CC will continue to be appointed concurrently as the Representative Colonel Commandant. RAA Colonels Commandant (15 June 1955 – 16 February 2019) Queensland 5 Aug 1958 – 22 Sep 1963 - Northern Command - BRIG CH Wilson, ED, RL 23 Sep 1963 – 15 Oct 1965 – Northern Command – MAJGEN HGF Harlock, CBE, RL 16 Oct 1965 - 31 Dec 1969 - Northern Command - MAJGEN DR Kerr CBE, ED, RL 1 Jan 1970 – 14 Mar 1974 – Northern Command - Brigadier CC Thomas ED, RL 15 Mar 1974 – 13 Apr 1978 - 1st Military District - Colonel GW Kerruish, ED, RL 14 Apr 1978 – 14 Mar 1982 - 1st Military District – BRIG CTW Dixon, RL 15 Mar 1982 – 16 July 1986 – 1st Military District – BRIG PJ Norton, RL 17 July 1986 - 16 July 1992 - 1st Military District - COL PC Jones (Retd) 17 Jul 1992 - 22 Jun 1996 - 1st Military -

Pakistan's Army

Pakistan’s Army: New Chief, traditional institutional interests Introduction A year after speculation about the names of those in the race for selection as the new Army Chief of Pakistan began, General Qamar Bajwa eventually took charge as Pakistan's 16th Chief of Army Staff on 29th of November 2016, succeeding General Raheel Sharif. Ordinarily, such appointments in the defence services of countries do not generate much attention, but the opposite holds true for Pakistan. Why this is so is evident from the popular aphorism, "while every country has an army, the Pakistani Army has a country". In Pakistan, the army has a history of overshadowing political landscape - the democratically elected civilian government in reality has very limited authority or control over critical matters of national importance such as foreign policy and security. A historical background The military in Pakistan is not merely a human resource to guard the country against the enemy but has political wallop and opinions. To know more about the power that the army enjoys in Pakistan, it is necessary to examine the times when Pakistan came into existence in 1947. In 1947, both India and Pakistan were carved out of the British Empire. India became a democracy whereas Pakistan witnessed several military rulers and still continues to suffer from a severe civil- military imbalance even after 70 years of its birth. During India’s war of Independence, the British primarily recruited people from the Northwest of undivided India which post partition became Pakistan. It is noteworthy that the majority of the people recruited in the Pakistan Army during that period were from the Punjab martial races. -

Biographies Introduction V4 0

2020 www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Author: Robert PALMER, M.A. BRITISH MILITARY HISTORY BIOGRAPHIES An introduction to the Biographies of officers in the British Army and pre-partition Indian Army published on the web-site www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk, including: • Explanation of Terms, • Regular Army, Militia and Territorial Army, • Type and Status of Officers, • Rank Structure, • The Establishment, • Staff and Command Courses, • Appointments, • Awards and Honours. Copyright ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk (2020) 13 May 2020 [BRITISH MILITARY HISTORY BIOGRAPHIES] British Military History Biographies This web-site contains selected biographies of some senior officers of the British Army and Indian Army who achieved some distinction, notable achievement, or senior appointment during the Second World War. These biographies have been compiled from a variety of sources, which have then been subject to scrutiny and cross-checking. The main sources are:1 ➢ Who was Who, ➢ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, ➢ British Library File L/MIL/14 Indian Army Officer’s Records, ➢ Various Army Lists from January 1930 to April 1946: http://www.archive.org/search.php?query=army%20list ➢ Half Year Army List published January 1942: http://www.archive.org/details/armylisthalfjan1942grea ➢ War Services of British Army Officers 1939-46 (Half Yearly Army List 1946), ➢ The London Gazette: http://www.london-gazette.co.uk/, ➢ Generals.dk http://www.generals.dk/, ➢ WWII Unit Histories http://www.unithistories.com/, ➢ Companions of The Distinguished Service Order 1923 – 2010 Army Awards by Doug V. P. HEARNS, C.D. ➢ Various published biographies, divisional histories, regimental and unit histories owned by the author. It has to be borne in mind that discrepancies between sources are inevitable. -

SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, I JANUARY, 1944

IO SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, i JANUARY, 1944 The KING has been graciously pleased, on Lieutenant-Colonel (temporary Brigadier) John the advice of His Majesty's Australian Minis- Mather Kirkman (14277), Royal Artillery. ters, to give orders for the following appoint- Colonel Edward Prince Lloyd, D.S.O. (5207), ments to the Most Excellent Order of the British late The Royal Northumberland Fusiliers. Empire: — Colonel (temporary Brigadier) Charles Falkland To be Additional Members of the Military °Loewen (17987), late Royal Artillery. Division of the said Most Excellent Order:— Colonel John Plunkett Magrane, E.D., Fiji Military Forces. Lieutenant Commander . Ronald Alexander Lieutenant-Colonel (temporary Brigadier) Denovan, R.A.N.V.R: Morgan Cyril Morgan, M.C. (4836), The Lieutenant John Charles Elley, Royal Aus- South Wales Borderers. tralian Navy. Colonel (temporary Brigadier) Charles Scott Napier, O.B.E. (27784), late Royal CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS Engineers. OF KNIGHTHOOD. Lieutenant-Colonel (temporary Brigadier) John Lenox Clavering Napier (15287), Royal Tank St. James's Palace, S.W.I. Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps. ist January, 1944. Colonel (temporary Brigadier) Alfred Geoffrey The KING has been graciously pleased to Neville, M.C. (1791), late Royal Artillery. give orders for the following promotions in, Colonel Joseph Clive Piggott, M.C., Warwick- and appointments to, the Most Excellent Order shire Home Guard. of the British Empire: — Colonel George James Paul St. Clair, D.S.O. To be Additional Knights Commanders of the (1050), late Royal Artillery. Military Division of the said Most Excellent Colonel Cecil Llewellyn Samuelson, O.B.E., Buckinghamshire Home Guard. Order:— Colonel (temporary Brigadier) Gilbert John Major-General Henry Guy Riley, C.B. -

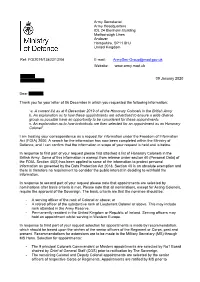

Information Regarding the Appointment of All Honorary Colonels in the British Army

Army Secretariat Army Headquarters IDL 24 Blenheim Building Marlborough Lines Andover Hampshire, SP11 8HJ United Kingdom Ref: FOI2019/13423/13/04 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.army.mod.uk XXXXXX 09 January 2020 xxxxxxxxxxxxx Dear XXXXXX, Thank you for your letter of 06 December in which you requested the following information: “a. A current list as at 6 December 2019 of all the Honorary Colonels in the British Army b. An explanation as to how these appointments are advertised to ensure a wide diverse group as possible have an opportunity to be considered for these appointments c. An explanation as to how individuals are then selected for an appointment as an Honorary Colonel” I am treating your correspondence as a request for information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) 2000. A search for the information has now been completed within the Ministry of Defence, and I can confirm that the information in scope of your request is held and is below. In response to first part of your request please find attached a list of Honorary Colonels in the British Army. Some of this information is exempt from release under section 40 (Personal Data) of the FOIA. Section 40(2) has been applied to some of the information to protect personal information as governed by the Data Protection Act 2018. Section 40 is an absolute exemption and there is therefore no requirement to consider the public interest in deciding to withhold the information. In response to second part of your request please note that appointments are selected by nominations after basic criteria is met. -

British Brigadier-Generals Major-Generals Lieutenant

BRITISH BRIGADIER-GENERALS MAJOR-GENERALS LIEUTENANT-GENRALS WHO HELD SENIOR POSITIONS IN THE CANADIAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCE 1 Lieutenant-General Sir Edwin Alfred Hervey ALDERSON, KCB Commander – 1 Canadian Corps Born: 08/04/1859 Capel St. Mary, England Married: 05/1886 Alice Mary Sergeant Died: 14/12/1927 Lowestoft, England Honours 1916 KCB 1900 CB Brigadier-General 1900 ADC Queen Victoria 1883 Gold Medal Royal Humane Society Military 1876 Lieutenant Norfolk Militia Artillery 1878 Lieutenant 91st Foot (His Father’s Regiment) 1880 Lieutenant Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment (renamed) 1880 Lieutenant QORWK Regiment in Halifax, Nova Scotia 1881 Lieutenant QORWK Regiment to Gibraltar 1881 Lieutenant Mounted Infantry Depot, Laing’s Nek S.A. 1881 Lieutenant First Boer War 1883 Lieutenant Mounted Camel Regiment for Relief of Khartoum 1884 Captain European Mounted Infantry Depot Aldershot 1890 Captain Adjutant Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment 1894 Major Staff College, Camberley 1896 Lieutenant-Colonel Mashonaland Commanding Local Troops 1897 Lieutenant-Colonel Return to Aldershot 1900 Brigadier-General Mounted Infantry Depot South Africa 1903 Brigadier-General Commander 2nd British Brigade at Aldershot 1906 Major-General Cdr 6th Infantry Division Poona, South India 1912 Major-General Semi-Retirement as Hunt Master in Shropshire 1914 Major-General Commander East Anglian Yeomanry 25/09/1914 Lieutenant-General Appointed Commander 1st Canadian Division 1915 Lieutenant-General Commanding 1st Canadian Division in France 04/1916 Lieutenant-General -

4244 SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, N JULY, 1940

4244 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, n JULY, 1940 Major-General Harold Edmund Franklyn, Lieutenant-General James Handyside Marshall- D.S.O., M.C., Colonel, The Green Howards Cornwall, C.B., C.B.E., D.S.O., M.C., (Alexandra, Princess of Wales's Own Colonel Commandant, Royal Artillery. Yorkshire Regiment). Lieutenant-General Henry Maitland Wilson, Major-General Giffard Le Quesne Martel, C.B., D.S.O., Colonel Commandant, The D.S.O., M.C., M.I.Mech.E. (late Royal Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort's Own). Engineers). Major-General Hastings Lionel Ismay, C.B., Major-General Bernard Law Montgomery, D.S.O., Indian Army. D.S.O. (late The Royal Warwickshire Regi- ment) . To be Additional Members of the Military Divi- Major-General Ridley Pakenham Pakenham- sion of the Third Class, or Companions, of Walsh, M.C. (late Royal Engineers). the said Most Honourable Order: Major-General Roderic Loraine Petre, D.S.O., Major-General (acting Lieutenant-General) M.C. (late The Dorsetshire Regiment). Hugh Royds Stokes Massy, D.S.O., M.C. (late Royal Artillery). Major-General Henry Osborne Curtis, D.S.O., Major-General (acting Lieutenant-General) M.C. (late The King's Royal Rifle Corps). Arthur Nugent Floyer-Acland, D.S.O., M.C. Major-General Kenneth Arthur Noel Anderson, (late The Duke of Cornwall's Light M.C. (late The Seaforth Highlanders (Ross- Infantry). shire Buffs, The Duke of Albany's)). Major-General (acting Lieutenant-General) Colonel (acting Major-General) Noel Henry Colville Barclay Wemyss, D.S.O., Mackintosh Stuart Irwin, D.S.O., M.C. -

G.H.Q. India General Staff Branch

2020 www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Author: Robert PALMER, M.A. GENERAL STAFF BRANCH, G.H.Q. INDIA (HISTORY & PERSONNEL) A short history of General Headquarters India Command between 1938 and 1947, and details of the key appointments held in G.H.Q. India during that period. Copyright ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk (2012)] 1 October 2020 [GENERAL STAFF BRANCH, G.H.Q. INDIA] A Concise History of the General Staff Branch, Headquarters the Army in India Version: 1_1 This edition dated: 19 June 2020 ISBN: Not yet allocated. All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means including; electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, scanning without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Author: Robert PALMER, M.A. (copyright held by author), Assisted by: Stephen HEAL Published privately by: The Author – Publishing as: www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk ©www.BritishMilitaryH istory.co.uk Page 1 1 October 2020 [GENERAL STAFF BRANCH, G.H.Q. INDIA] Headquarters, the Army in India The General Staff Branch Headquarters of the Army in India was a pre-war command covering the entire country of British India. The headquarters consisted of five branches: • General Staff Branch, • Adjutant General’s Branch, • Quarter-Master-General’s Branch, • Master-General of the Ordnance Branch, • Engineer-in-Chief’s Branch. At the beginning of the Second World War, the headquarters was redesignated as the General Headquarters (G.H.Q.), India Command. The General Staff (G.S.) Branch was seen the foremost of the branches at General Headquarters. -

The Royal Artillery Day (26 May) the Anniversary of the Formation Master Gunner on Appropriate Occasions

Artillery. The tour of duty is from 1st April to 31st March. The duties Institution Committee and the Board of Management of the Royal Annual Events include visiting Royal Artillery Stations and units and representing the Artillery Charitable Fund and Royal Artillery Association. Regiment at public events. He may also be asked to deputise for the Royal Artillery Day (26 May) The Anniversary of the Formation Master Gunner on appropriate occasions. The RAI, founded in 1838, of the Regiment. The Royal Artillery Institution is responsible for funds, property and support to the serving Up to three gentlemen of Regiment including sports, the Royal Artillery Band, historical St Barbara’s Day (4 December) St Barbara’s Day may be Honorary Colonels Commandant distinction with Gunner connections may be appointed as Honorary affairs, ceremonies and events, management and improvement of celebrated by church parades or social functions and may be Colonels Commandant. Regimental capital property, central messes, publications, and direct observed instead of Royal Artillery Day. St Barbara’s Day is an support to Units, recruiting and education. appropriate day for exchanges of greetings or celebrations in The Director Royal Artillery is the conjunction with the Artilleries of allied foreign armies. The Director Royal Artillery professional head of the Regiment. The Royal Artillery Charitable Fund The RACF is the Regimental Charitable Fund of the Royal Artillery; it dates from 1839 Remembrance Day The Royal Artillery Ceremony of The RASM, an when it was formed to provide relief for wives and children and non Remembrance takes place annually on Remembrance Sunday at the The Royal Artillery Sergeant Major appointment created in 1989, is the Senior WO1 in the Regiment commissioned officers and privates of the Royal Artillery embarked on Royal Artillery Memorial at Hyde Park Corner. -

87Th Regiment of Foot Secondary Title: Prince of Wales' Irish (Until 1811); Thence Prince of Wales' Own Irish

The Napoleon Series British Infantry Regiments and the Men Who Led Them 1793-1815 By Steve Brown 87th Regiment of Foot Secondary Title: Prince of Wales' Irish (until 1811); thence Prince of Wales' Own Irish Regimental History, 87th Regiment of Foot 1793: 18 September - Raised as the 87th (The Prince of Wales's Irish) Regiment of Foot by John Doyle 1804: 2nd Battalion formed at Frome 1817: 2nd Battalion disbanded at Colchester 1827: 87th Regiment of Foot (Prince of Wales's Own Irish Fusiliers) 1827: 87th (Royal Irish Fusiliers) Regiment of Foot 1881: 1st Battalion, Princess Victoria's (Royal Irish Fusiliers) on amalgamation with the 89th Regiment of Foot 1920: The Royal Irish Fusiliers (Princess Victoria's) 1947: Grouped with the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers and Royal Irish Fusiliers into the North Irish Brigade 1968: The Royal Irish Rangers (27th (Inniskilling) 83rd and 87th) on amalgamation with the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers and Royal Irish Fusiliers 1991: The Royal Irish Regiment (27th (Inniskilling) 83rd and 87th and Ulster Defence Regiment) on amalgamation with the Ulster Defence Regiment Service History and Demographics, 1st Battalion 87th Regiment of Foot 1793: September - raised in Ireland by Major John Doyle; Dublin 1794: Dublin; February - to England; Parkgate; June - Hilsea; Southampton; to Flanders; July - Alost; line of Waal River 1795: Battalion taken POW at capitulation of Bergen-Op-Zoom; held POW in Amiens and Rouen 1796: POWs released, to England; August - Chatham; September - aboard fleet as marines; Texel (did not