Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. John's Visitorinformation Centre 17

Admirals' Coast ista Bay nav Baccalieu Trail Bo Bonavista ± Cape Shore Loop Terra Nova Discovery Trail Heritage Run-To Saint-Pierre et Miquelon Irish Loop Port Rexton Trinity Killick Coast Trans Canada Highway y a B Clarenville-Shoal Harbour y it in r T Northern Bay Goobies y Heart's a B n Content o ti p e c n o C Harbour Arnold's Cove Grace Torbay Bell Harbour Cupids Island \!St. John's Mille Brigus Harbour Conception Mount Pearl Breton Bay South y Whitbourne Ba Fortune Argentia Bay Bulls ay Witless Bay y B err ia F nt n ce lo Marystown la e Grand Bank P u q i Fortune M t Burin e Ferryland e r r St. Mary's e St. Lawrence i y P a - B t 's n i Cape St. Mary's ry a a Trepassey M S t. S rry Nova Scotia Fe ssey B pa ay Cape Race re T VIS ICE COUNT # RV RD ST To Bell Island E S T T Middle R O / P R # T I Pond A D A o I R R W P C E 'S A O N Y G I o R B n T N B c H A O e R 50 E D p M IG O O ti E H I o S G D n S T I E A A B N S R R G C a D y E R R S D ou R th Left Pon T WY # St. John's o R H D E R T D U d r T D a H SH S R H T n IT U E R Left To International # s G O O M M V P C R O R a S A AI Y E B R n D T Downtown U G Airport h a A R c d R a L SEY D a H KEL N e R B ig G y hw OL D ve a DS o b ay KIWAN TO r IS N C o ST E S e T T dl o id T City of M MAJOR 'SP AT Oxen Po Pippy H WHIT Mount Pearl nd E ROSE A D L R L Park L P A Y A N P U D S A IP T P IN L 8 1 E 10 ST R D M OU NT S CI OR K D E O NM 'L E O EA V U M A N RY T O A N R V U D E E N T T E 20 D ts S RI i DG F R C E R O IO D E X B P 40 im A L A ST PA L V K DD E C Y O A D y LD R O it P A ENN -

Heritage Building and Public Views

3.6 Master List of Heritage Structures for the City of St. John’s The Master List is made up of all properties presently designated by the Provincial, Federal or Municipal Governments and all priority buildings requiring protection. Properties that presently hold a Municipal designation are indicated. Currently # Name/Building Type Address Designated 1 House 8-10 Barnes Road X 2 Mallard Cottage 2 Barrow's Road, Quidi Vidi X 3 Murray Premises 5 Beck's Cove (Harbour Dr./ Water St.) X 4 House 64 Berteau Avenue 5 St. Joseph's Chapel Blackhead X 6 Cape Spear Lighthouse Blackhead Road 7 St. Bonaventure's College Bonaventure Avenue 8 The Observatory (house) 1 Bonaventure Avenue X 9 Fort Townshend Bonaventure Avenue 10 St. Michael's Convent Bonaventure Avenue –Belvedere X 11 Belvedere Orphanage Bonaventure Avenue -Belvedere X 12 Bishop Field College 44 Bond Street X 13 Cathedral Clergy House 9 Cathedral Street X 14 Masonic Temple Cathedral Street X 15 Fort William Cavendish Square at Duckworth Street Anglican Cathedral of St. John 16 22 Church Hill X the Baptist 17 Cathedral Rectory 23 Church Hill X 18 House 2 Circular Road 19 House 24 Circular Road X 20 Bartra 28 Circular Road X 21 Houses 34-36 Circular Road X 22 Bannerman House 54 Circular Road X 23 House 56 Circular Road 24 House 58 Circular Road 25 House 60 Circular Road 26 House 70 Circular Road 27 Canada House 74 Circular Road X 28 Cochrane Street United Church Cochrane Street X 29 Former House 28 Cochrane Street 30 House 82 Cochrane Street 31 Emmanuel House 83 Cochrane Street X 32 St. -

NL Writers/Literature – Joan Sullivan (Guest Editor)

Week of August 24 – NL Writers/Literature – Joan Sullivan (guest editor) Wikipedia Needs Assessment – NL Writers/Literature A Selection of Existing Articles to Improve: Megan Gail Coles: Can be expanded Mary Dalton: Can be expanded Stan Dragland: Can be expanded Margaret Duley: Needs more citations Percy Janes: Needs more citations Maura Hanrahan: Needs citations Michael Harrington: Needs citations and can be expanded Kenneth J. Harvey: Needs more citations and a more neutral point of view Andy Jones: Can be expanded and needs more citations Kevin Major: Can be expanded and needs more citations Elisabeth de Mariaffi: Can be expanded Janet McNaughton: Can be expanded George Murray: Needs more citations and can be updated 1 Patrick O’Flaherty: Can be expanded and needs more citations Al Pittman: Needs citations Bill Rowe: Needs more citations Dora Oake Russell: Can be expanded and needs more citations Winterset Award: Can be expanded Russell Wangersky: Needs more citations These lists could also be checked to see if any of the existing articles need expansion, improvement or citations: • Wikipedia’s list on Writers from St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador • Wikipedia’s list on Writers from Newfoundland and Labrador Suggested New Articles to Create: Smokey Elliott (poet) Carol Hobbs (poet) Charis Cotter (YA author) Running the Goat Books & Broadsides Uncle Val, Andy Jones’ fictional character Online Resources on NL Writers/Literature “Literature” in Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador Volume 3, pp. 320-333. Literature – Heritage NL Web Site Poetry Bibliography – Heritage NL Web Site Writers – Heritage NL Web Site Also consult Online Resources with Newfoundland and Labrador Content. -

Escribe Agenda Package

AGENDA REGULAR MEETING Monday, March 2, 2020 4:30 p.m. MEMORANDUM February 28, 2020 In accordance with Section 42 of the City of St. John’s Act, the Regular Meeting of the St. John’s Municipal Council will be held on Monday, March 2, 2020 at 4:30 p.m. By Order Elaine Henley City Clerk Regular Meeting - City Council Agenda March 2, 2020 4:30 p.m. 4th Floor City Hall Pages 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. PROCLAMATIONS/PRESENTATIONS 2.1 Dietitians of Canada Nutrition Month 4 2.2 National Lymphedema Awareness Month 5 3. APPROVAL OF THE AGENDA 3.1 Adoption of Agenda 4. ADOPTION OF THE MINUTES 4.1 Adoption of Minutes - February 24, 2020 6 5. BUSINESS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES 5.1 75 Airport Heights Drive MPA1800006 22 Listed under Notices Published Report 6. NOTICES PUBLISHED 75 6.1 217 Brookfield Road - Rural Residential Infill/Rural (RRI/R) Zone - Ward 5 Application A change of Non-Conforming Use application has been submitted by Executive Taxi Services Ltd. requesting to operate a Commercial Garage at 217 Brookfield Road. Description The proposed business will operate Monday - Saturday 7 a.m.- 7 p.m. and will employee two employees. 7. COMMITTEE REPORTS 7.1 Committee of the Whole Report - February 26, 2020 (Partial Report) 76 1. 2020 Community Capital Grants 78 2. 2020 Community Grants 81 8. DEVELOPMENT PERMITS LIST (FOR INFORMATION ONLY) 9. BUILDING PERMITS LIST 9.1 Building Permits List for the week ending February 26, 2020 91 10. REQUISITIONS, PAYROLLS AND ACCOUNTS 10.1 Weekly Payment Vouchers for week ending February 26, 2020 94 11. -

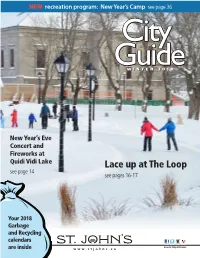

Lace up at the Loop See Page 14 See Pages 16-17

NEW recreation program: New Year’s Camp see page 36 City GuideWINTER 2018 New Year’s Eve Concert and Fireworks at Quidi Vidi Lake Lace up at The Loop see page 14 see pages 16-17 Your 2018 Garbage and Recycling calendars Search: CityofStJohns are inside www.stjohns.ca Celebrating 25 Years of Building Excellence Our team has built an industry-leading service by providing exceptional craftsmanship and forging strong relationships with our customers. Call us today for a FREE consultation, we are always happy to give advice on building homes, renovations, land purchases and our latest designs. newvictorianhomes.ca 709 738 7000 #NVHomes 7557601 EXCITE YOUR SENSES THIS WINTER WEEKEND FAMILY FUN AN INTIMATE EVENING LEARN TO PLAY WITH ANITA BEST Coming & PAMELA MORGAN this Dec 7 | 8 pm winter Dec 20 | 120 Jan 31 | Feb s28 Check us out at therooms.ca for a full list of programs and events. 7566342 4 City Guide / Winter 2018 www.stjohns.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS City Directory City Directory .........................................................................................Page 4 Access St. John’s City Council ...................................................................................... Pages 6-7 City Hall, first floor, 10 New Gower Street Waste & Recycling ......................................................................Pages 8-11 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday to Friday Waste Collection Calendars ..............................................Pages 12-13 Winter Celebrations ...............................................................Pages -

Escribe Agenda Package

Committee of the Whole Agenda March 10, 2021 9:30 a.m. 4th Floor City Hall Pages 1. Call to Order 2. Approval of the Agenda 3. Adoption of the Minutes 3.1. Adoption of Minutes - February 24, 2021 3 4. Presentations/Delegations 5. Finance & Administration - Councillor Shawn Skinner 5.1. Travel Report for the Year Ended December 31, 2020 15 6. Public Works - Councillor Sandy Hickman 7. Community Services - Councillor Jamie Korab 7.1. Inclusion Advisory Committee Report - February 9, 2021 20 1. APS and Key 2 Access Update 22 7.2. Capital Grant Allocations 2021 28 7.3. Grant Allocations 2021 32 8. Special Events - Councillor Shawn Skinner 9. Housing - Deputy Mayor Sheilagh O'Leary 9.1. Housing Division Update 45 10. Economic Development - Mayor Danny Breen 11. Tourism and Culture - Councillor Debbie Hanlon 12. Governance & Strategic Priorities - Mayor Danny Breen 13. Planning & Development - Councillor Maggie Burton 13.1. 22 Shaw Street, REZ2000013 49 13.2. 350 Kenmount Road and 9 Kiwanis Street, MPA2000011 60 14. Transportation and Regulatory Services & Sustainability - Councillor Ian Froude 14.1. St. John’s Collision Report (2012 70 14.2. What We Heard – Initial Community Conversations for Resilient St. 92 John’s Community Climate Plan 15. Other Business 16. Adjournment Page 2 of 111 Minutes of Committee of the Whole - City Council Council Chambers, 4th Floor, City Hall February 24, 2021, 9:30 a.m. Present: Mayor Danny Breen Councillor Maggie Burton Councillor Sandy Hickman Councillor Debbie Hanlon Councillor Deanne Stapleton Councillor -

Sample Chapter

6 courtesy Parks canada St. John’s Most people don’t come to Newfoundland for city life, but once in the province they invariably rave about St. John’s. The city is responsible for a good part of the province’s economic output, and is home to Memorial University. The 2006 census has the city population at a modest 100,000, but the metro area count is 180,000 and fast-growing. St. John’s is a region unto itself. It was the capital of the Dominion of Newfoundland and Labrador prior to Confederation with Canada in 1949. As such, it retains elements (and attitudes) of a national capital and is, of course, the provincial capital. St. John’s claim to be the oldest European- settled city in North America is contested, however, it is clear that it was an important fishing port in the early 1500s and received its first permanent settlers in the early 1600s. Moreover, there is no doubt that Water Street is the oldest commercial street in North America. Formerly known as the lower path, it was the route by which fishermen, servants, and traders (along with pirates and naval officers) moved from storehouse, to ware- house to alehouse. They did so in order to purchase or barter the supplies necessary to secure a successful voyage at the Newfoundland fishery. Centuries later, the decline of the fishery negatively affected St. John’s, but oil and gas discoveries, and a rising service sector, have boosted the city’s fortunes. For visitors, St. John’s memorably hilly streets, fascinating architecture, and spectacular harbour and cliffs make it the perfect place 7 to begin (or end) a trip to Newfoundland. -

Gerald Leopold Squires 1937-2015

GERALD LEOPOLD SQUIRES 1937-2015 Chronology 1937 Born in Change Islands, Newfoundland, November 17th. His parents are Salvation Army officers Samuel and Mabel (Payne) Squires. 1939 At the outbreak of World War II, father leaves the family in Greenspond, to join the Newfoundland Overseas Forestry Unit in Scotland while mother continues her work with the Salvation Army. 1939-45 Mother and children live successively at Exploits, Long Pond, Green’s Harbour and again Exploits. 1945 Father returns from overseas and mother resigns from her work with the Salvation Army. Mabel and the boys move in with Samuel’s parents in Bonavista until he finds work with the Bowater Paper Company in Corner Brook, where mother buys a house on Bayview Heights. Here they live together as a family. 1947 Father moves to Toronto, Ontario, for work. 1949 Mother leaves Corner Brook with her three sons, David, Gerald and Fraser to join Samuel in Toronto. 1950 2 Attends Gledhill Public School, Toronto. Here he first meets Ken Watson, who becomes a fellow artist and a lifelong friend. 1954 Enrolls in the four-year art program at Danforth Technical School, Toronto, (now Danforth Collegiate and Technical Institute). Goes on many sketching trips, often with teacher Dan Logan, artist friends, and like-minded classmates. 1957 Graduates from Danforth Technical School, Toronto, majoring in commercial and fine arts. He apprentices as a stained-glass artist with McCausland’s Stained Glass Studio, Toronto and works part-time as an editorial artist with the Toronto Telegram. With Dan Logan and Ken Watson, he rents rooms to use as studios in a large house at Avenue Road and Yorkville in Toronto. -

The Geography Collection COLL-137

ARCHIVES and SPECIAL COLLECTIONS QUEEN ELIZABETH II LIBRARY MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY, ST. JOHN'S, NL The Geography Collection COLL-137 Website: http://www.library.mun.ca/qeii/cns/archives/cnsarch.php Author: Linda White and Claire Jamieson Date: 1999 Scope and Content: The Geography Collection consists of 1109 black and white photographs together with contact prints and negatives. These photographs depict many images of Newfoundland and Labrador houses, churches, public buildings, ships, railways, communities, and special events. The creation of these photographs was primarily the work of three prominent photographers: Robert Holloway, S.H. Parsons and James Vey. Through a special project initiated by the Geography Department of Memorial University of Newfoundland, the photographs were copied from the original glass negatives that were in the custody of the Newfoundland Museum but are now on deposit in the Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador. They were arranged and described in an annotated guide to the collection, The Historic Photographic Collection of the Department of Geography, in three volumes by Dr. Maurice Scarlett, professor of Geography, Memorial University of Newfoundland, and his wife, Shirley Scarlett. These photographs will be of interest to anyone seeking historic photographs of Newfoundland and Labrador. Custodial History: The photographs in this collection were copied from glass negatives held at the Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador. They were copied, arranged and described by members of the Geography Department, Memorial University of Newfoundland, including Michael Crane and Dr. Maurice Scarlett. Upon his retirement, Dr. Scarlett donated the photographs and negatives to Archives and Special Collections. Restrictions: There are no restrictions on access to or use of the materials in this collection. -

Vertical Files

Vertical Files A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U - V | W | X - Y | Z A A1 Automotive Ltd. A2Z (musical group) A & E Computer Services A & R Services Ltd. A & W Restaurant ABA Access (company) A.B.M. see Lundrigans ACAP (Atlantic Coastal Action Plan) SA St. John's Harbour A.C.C.E.S.S. see Association for Co-operative Community Living, Education & Support Services ACE (Association of Collegiate Entrepreneurs) see M.U.N. - ACE ACE (Atlantic Container Express) SA Oceanex A.C.E. (Atlantic Container Express) see ACE ACME Financial Inc. A.C.O.A. see Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency ACRO-ADIX School of Acrobatics ADI Nolan Davis (NF) Limited AE Bridger (musical group) A.E. Hickman Co. Ltd. A.E. Services Ltd. 1 A/F Protein Canada Inc. AGRA Earth & Environmental Limited A.H.M. Fabricators Limited A.H. Murray & Co. SA St. John's Buildings & Heritage - Murray Premises A. Harvey & Co. A.J. Holleman Engineering Ltd. A.J. Marine A.L. Collis & Son Ltd. A.L. Stuckless Ltd. A.L.S. Society of Canada (Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis) A.M. Carew Gallery AM/FM Dreams (musical group) AMI Offshore Inc. A.M.P. Fisheries Ltd. A.N.D. Co. Ltd. (Anglo Nfld. Dev. Co. Ltd.) A.N.D. Company Players (theatre group) A.P.L.A. see Atlantic Provinces Library Assoc. APPA Communications (after May 1992, see: Bristol Communications Inc.) ARDA see Rural Development ATV Association of Newfoundland and Labrador A Dollar a Day Foundation SA Health - Mental A Legge Up Therapeutic Riding Facility Aaron's Sales and Lease Ownership 2 Abbacom Logic Corporation Abbott Brothers (musical group) Abbeyshot Clothiers Abilities (store) Ability Works Abitibi-Price Inc. -

Escribe Agenda Package

Committee of the Whole Agenda August 5, 2020 9:00 a.m. 4th Floor City Hall Pages 1. Call to Order 2. Approval of the Agenda 3. Adoption of the Minutes 3.1 Adoption of Minutes - July 22, 2020 3 4. Presentations/Delegations 5. Finance & Administration - Councillor Dave Lane 6. Public Works & Sustainability - Councillor Ian Froude 6.1 St. John's Transportation Commission - Q2 Financial Statement 8 7. Community Services - Councillor Jamie Korab 8. Special Events - Councillor Hope Jamieson 9. Housing - Deputy Mayor Sheilagh O'Leary 10. Economic Development - Mayor Danny Breen 11. Tourism and Culture - Councillor Debbie Hanlon 12. Governance & Strategic Priorities - Mayor Danny Breen 13. Planning & Development - Councillor Maggie Burton 13.1 750 Kenmount Road - Zone Line Interpretation - DEV1400357 17 13.2 78 McNiven Place - Zone Line Interpretation - INT1900047 20 13.3 5 and 7 Little Street - MPA2000003 23 13.4 6 Lambe’s Lane - MPA2000005 37 14. Transportation and Regulatory Services - Councillor Sandy Hickman 15. Other Business 16. Adjournment Page 2 of 56 Minutes of Committee of the Whole - City Council Council Chambers, 4th Floor, City Hall July 22, 2020, 9:00 a.m. Present: Mayor Danny Breen Deputy Mayor Sheilagh O'Leary Councillor Dave Lane Councillor Sandy Hickman Councillor Debbie Hanlon Councillor Deanne Stapleton Councillor Hope Jamieson Councillor Jamie Korab Councillor Ian Froude Councillor Wally Collins Regrets: Councillor Maggie Burton Staff: Kevin Breen, City Manager Derek Coffey, Deputy City Manager of Finance & Administration -

July 23, 2007 the Regular Meeting of the St. John's Municipal Council Was Held in the Council Chamber, City Hall, at 4:30

July 23, 2007 The Regular Meeting of the St. John’s Municipal Council was held in the Council Chamber, City Hall, at 4:30 p.m. today. His Worship the Mayor presided. There were present also Deputy Mayor O’Keefe, Councillors Colbert, Hickman, Hann, Puddister, Galgay, Coombs, Ellsworth and Collins. Regrets: Councillor Duff The Chief Commissioner/City Solicitor, Associate Commissioner/Director of Corporate Services and City Clerk, Associate Commissioner/Director of Engineering, Director of Planning, and Manager, Corporate Secretariat were also in attendance. Call to Order and Adoption of the Agenda SJMC2007-07-23/401R It was decided on motion of Councillor Ellsworth, seconded by Deputy Mayor O’Keefe: That the Agenda be adopted as presented with the following additional item: a. Memorandum dated July 23, 2007 from the Chief Commissioner and City Solicitor re: MacMorran Community Centre, St. John’s Community Alliance Centre Inc. Adoption of Minutes SJMC2007-07-23/402R It was decided on motion of Councillor Ellsworth; seconded by Deputy Mayor O’Keefe: That the Minutes of the July 23rd, 2007 meeting be adopted as presented. Kilbride Concept Plan Under business arising, Council considered a memorandum dated July 19, 2007 from the Director of Planning regarding the above noted. SJMC2007-07-23/403R It was moved by Councillor Collins; seconded by Councillor Hann: That the following Resolutions for Municipal Plan Amendment Number 49, 2007 and Development Regulations Amendment Number 409, 2007 be adopted as - 2 - 2007-07-23 presented, and further, that a public hearing be scheduled on the amendments to take place on August 13, 2007, and that Mr.