Chief Executive Officer Power Message Types As a Function of Organizational Target Types

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Stretched to Strengthened

The illustration on the cover of this report represents more than 1,700 Chief Marketing Officers (CMOs) who spoke with IBM as part of this study. Each facet represents approximately 23 participants and the colours on the front cover represent the three imperatives identified in our analysis: deliver value to empowered customers; foster lasting connections; and capture value, measure results. For more information, please turn to page 9. This study is based on face-to-face conversations with more than 1,700 CMOs worldwide. Jon Iwata Senior Vice President, Marketing & Communications IBM Corporation Letter from IBM’s Senior Vice President, Marketing & Communications 3 A note to fellow CMOs All of us are aware of the forces changing business and markets today. But it is not so easy to see what the marketing profession is turning into in response. To understand this, IBM undertook our first-ever Global CMO Study. We aimed for 1,000 participants. More than 1,700 CMOs from 64 countries spoke face to face with us for an hour. We believe it is the largest survey of its type ever conducted. It clearly speaks to a broad awareness of how our roles have evolved over the past decade. What did we find? Interestingly, your perspectives are in line with your colleagues across the executive suite. We know, because we have conducted more than 15,000 interviews with Chief Executive Officers (CEOs), Chief Financial Officers (CFOs), Chief Information Officers (CIOs), CHROs and CSCOs over the past seven years, as part of our C-suite research programme. Like CEOs, you told us that market and technology factors are the two most powerful external forces affecting your organisation today. -

Chief Marketing Officer & Senior Vice President for Strategic Engagement

Chief Marketing Officer & Senior Vice President for Strategic Engagement Position Description Under the general direction of the Chief Executive Officer, the CMO/SVP will oversee the development and delivery of the marketing and communications strategy for the V Foundation. The CMO/SVP will collaborate to develop opportunities that drive substantial growth in awareness, relevance, reach, and revenue. The individual will organize a vision for programming delivery and evaluation in partnership with the V Foundation’s executive team and Board of Directors. The CMO/SVP will work cross-functionally to understand and drive the revenue and engagement needs and goals of the organization, as well as develop and help execute an integrated marketing, communications, and fundraising plan. The CMO/SVP will lead the organization to adopt a best-practice mentality for the use of data, research, metrics, and analytics to drive sophisticated and robust stakeholder engagement. The successful candidate will be goal-oriented, inquisitive, creative, mission-driven, and a collaborative team player who can unlock potential to achieve transformational results. The CMO/SVP will possess the ability to enhance assets and the connection with core brand partners— including with our founding partner, ESPN—to add value across the relationships. The CMO/SVP will be a core member of the leadership team, accelerating the organization to achieve $100M in annual revenue. To achieve success, the CMO/SVP will oversee a team of 10-plus staff and advise the V Foundation on the appropriate resource requirements to advance a sophisticated and impactful integrated marketing and communications program. The individual will help develop our vision to initiate a partnership platform to grow transformational partnerships that achieve shared objectives and ensure sustainable, diversified revenue. -

Download Corporate Governance Guidelines

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE GUIDELINES The business of Bristol-Myers Squibb Company (the “Company”) is managed under the direction of the Board of Directors pursuant to the Delaware General Corporation Law and the Company's Bylaws. It has responsibility for establishing broad corporate policies and for the overall performance of the Company. The Board selects the senior management team that is responsible for the day-to-day operations of the Company and for keeping the Board advised of the Company's business. The Board acts as an advisor and counselor to senior management and ultimately monitors its performance. UComposition and Structure of the Board 1. Size of the Board. The Board in recent years has had between 10 and 12 members. This range permits diversity of perspectives and experience without hindering effective discussion. However, the Board is prepared to increase its membership if the Board deems it advisable, for example to bring new or specialized skills and talent to the Board. 2. Board Membership Criteria. The Committee on Directors and Corporate Governance is responsible for reviewing with the Board, on an annual basis, the appropriate criteria for membership to the Board. Generally, non-employee directors should be persons with broad experience in areas important to the operation of the Company such as business, science, medicine, finance/accounting, law, business strategy, crisis management, corporate governance, education or government and should possess qualities reflecting integrity, independence, leadership, good business judgment, wisdom, an inquiring mind, vision, a proven record of accomplishment and an ability to work with others. The Board believes that its membership should continue to reflect a diversity of gender, race, ethnicity, age, sexual orientation and gender identity. -

Draft CEO Role, Responsibilities and Duties

POSITION DESCRIPTION CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER The Chief Executive Officer ("CEO") of Precision Drilling Corporation (the "Corporation") is appointed under the authority of the Corporation's by-laws and the policies of the board of directors (the “Board” or "Board of Directors"). The CEO of the Corporation has two major roles: To direct and execute all activities of the Corporation either directly or through delegated authority; and To provide leadership in these and other areas: the creation of vision, strategic, tactical and financial plans; developing goals and measuring performance to the approved goals; organizational development; liaison to the public, investment community, government, affiliated organizations and other stakeholders; and the development of the Corporation's management and staff. RESPONSIBILITIES Authority The CEO operates under the authority granted by the Board pursuant to the Mandate set forth below and such extensions of authority as may be granted from time to time. The approval of the Board (or appropriate Board committee) shall be required for all significant decisions outside of the ordinary course of the Corporation's business, including major financings, acquisitions, dispositions, budgets and capital expenditures as set out in the Corporation's policies and procedures. Mandate The CEO possesses the highest personal and professional integrity. The CEO shall act honestly and in good faith with a view to the best interests of the Corporation and will exercise the care, diligence and skill that a reasonably prudent person would exercise in comparable circumstances. The CEO avoids potential or actual conflicts of interest with the Corporation or other interests which are incompatible with the position of CEO. -

DESCRIPTION the Chief Executive Officer, Under the Direction of The

Metro Gold Line Foothill Extension Construction Authority Job Description – Chief Executive Officer CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER DESCRIPTION The Chief Executive Officer, under the direction of the Board of Directors, provides overall leadership and direction to ensure the Construction Authority achieves its vision, mission, goals and objectives. Organizes and manages Construction Authority staff and contractors to provide effective and efficient transportation planning, and construction. TYPICAL TASKS, KNOWLEDGE AND DUTIES Examples of Duties • Approves and adopts Construction Authority’s policies, procedures; and maintains accountability for the performance of the entire agency • Provides overall leadership and staff direction in formulating and achieving Construction Authority’s objectives • Makes recommendations to the Board of Directors on significant matters affecting Construction Authority operations and policies • Oversees the development and implementation of short-range and long-range goals and business plans • Directs and manages staff to efficiently and effectively implement the policies and direction of the Board of Directors • Provides leadership for the region’s mobility agenda and coordinates regionally significant projects and programs by working collaboratively with regional partners • Oversees Construction Authority’s planning efforts, including identifying major priorities, establishing goals and strategies that ensure the success of the project • Works closely with the Municipal Operators to ensure coordination • Aggressively -

Chief Executive Officer Position Description

Position Description – Chief Executive Officer Mandate The Chief Executive Officer (“CEO”) of Barrick Gold Corporation (the “Company”) is appointed by the Board of Directors (the “Board”) and reports to the Executive Chairman and the Board. The CEO has overall responsibility, subject to the oversight of the Executive Chairman and the Board, for managing the Company’s business on a day-to- day basis, for general supervision of the business of the Company and the execution of the Company’s operating plans and, working with the Executive Chairman, execution of the Company’s strategic priorities. In fulfilling his executive role, the CEO acts within the authority delegated to him by the Executive Chairman and the Board. Responsibilities The CEO’s responsibilities shall include: 1. Leading the executives and senior management in the day to day running of the Company's business, under the supervision of the Executive Chairman and the Board. 2. Developing, in conjunction with the Executive Chairman, the Company strategy and objectives, and ensuring subsidiary companies' strategies are consistent with them. 3. Developing appropriate capital, corporate and management structures to ensure the Company's objectives can be met. 4. Monitoring the operational performance and strategic direction of the Company. 5. Managing the Company's internal control framework, including approving management and control policies. 6. Working to effect investments/dispositions and major contracts (within authorized limits). 7. Approving the Company's management development and succession plans for executives and senior management, in conjunction with the Executive Chairman and the Board where appropriate, and approving appointments and termination of staff reporting to executives or senior management. -

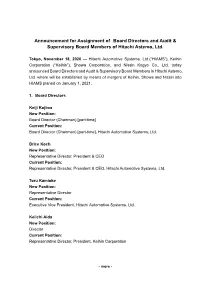

Announcement for Assignment of Board Directors and Audit & Supervisory Board Members of Hitachi Astemo, Ltd

Announcement for Assignment of Board Directors and Audit & Supervisory Board Members of Hitachi Astemo, Ltd. Tokyo, November 18, 2020 --- Hitachi Automotive Systems, Ltd.(“HIAMS”), Keihin Corporation (“Keihin”), Showa Corporation, and Nissin Kogyo Co., Ltd. today announced Board Directors and Audit & Supervisory Board Members in Hitachi Astemo, Ltd. where will be established by means of mergers of Keihin, Showa and Nissin into HIAMS planed on January 1, 2021. 1. Board Directors Keiji Kojima New Position: Board Director (Chairman) [part-time] Current Position: Board Director (Chairman) [part-time], Hitachi Automotive Systems, Ltd. Brice Koch New Position: Representative Director, President & CEO Current Position: Representative Director, President & CEO, Hitachi Automotive Systems, Ltd. Toru Kamioke New Position: Representative Director Current Position: Executive Vice President, Hitachi Automotive Systems, Ltd. Keiichi Aida New Position: Director Current Position: Representative Director, President, Keihin Corporation - more - - 2 - Yoshihiko Kawamura New Position: Director (part-time) Current Position: --- Yoshikado Nakao New Position: Director (part-time) Current Position: --- 2. Audit & Supervisory Board Members Atsushi Mitani New Position: Audit & Supervisory Board Member Current Position: Audit & Supervisory Board Member, HIAMS Shinji Suzuki New Position: Audit & Supervisory Board Member Current Position: Director and Managing Officer, Keihin Yukihito Imamura New Position: Audit & Supervisory Board Member Current Position: --- CEO:Chief -

Job Title: Senior Director of Marketing Department: Marketing Supervisor: Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Status: Exempt, Full-Time Approved Date: 04/04/2017

Job Title: Senior Director of Marketing Department: Marketing Supervisor: Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Status: Exempt, Full-Time Approved Date: 04/04/2017 Our Mission: "To create the most enjoyable shopping experience possible for our guests." Summary Known as the denim destination, Buckle strives to achieve its mission of creating the most enjoyable shopping experience possible for our guests by implementing creative marketing initiatives to engage them. The Senior Marketing Director will supervise all marketing operations of the company and will collaborate with the Chief Executive Officer and company executives to establish and execute Buckle’s marketing strategy and vision to drive new brand engagement and retain loyal guests. Primary Relationships As an important member of the management team, this person will report to the Chief Executive Officer, work closely with the senior management team, and collaborate on marketing projects throughout the company. Essential Duties and Responsibilities This description intends to describe the general nature and level of work performed by Teammates assigned to this job. It is not intended to include all duties, responsibilities and qualifications. To perform this job successfully, an individual must be able to perform each essential duty satisfactorily. Reasonable accommodations may be made to enable individuals with disabilities to perform the essential functions. Marketing In collaboration with the senior management team, responsible to help create, implement and measure the success of a comprehensive marketing program that will enhance Buckle’s position within the marketplace and the general public, and facilitate internal and external communications. Ensure articulation of Buckle’s desired image and position through consistent communication to all constituencies, both internal and external. -

The Role of the Chairman As Well As Value of a Non Executive Chairman

The role of the Chairman as well as value of a non executive chairman 1 Next The role of the Chairman and considerations in Independent Chairman appointing a non-executive Chairman The chairperson of the board is the individual charged It has become common for shareholders to attach more with providing the board with leadership, and to value to the quality of corporate governance structures. harness the talents and energy contributed by each of This is especially the case in public (listed) companies, the individual directors. where the company has many shareholders (some of whom may hold relatively diversified investment King III recommends that the chairperson should be an portfolios). Shareholders must be able to rely on independent non-executive director. The chairperson appropriate corporate governance structures, risk should not also be the CEO. While the chairperson is management systems and board processes to safeguard required to retain an objective viewpoint of the affairs their interests and ultimately enhance shareholder of the company, the CEO is often required to become value. Some of the indicators of a well-developed and intimately involved in developing and executing embedded corporate governance structure include: management plans for the company. high-calibre directors; independent board committees; effective board chairing; and prevention of the The independence of the chairman is paramount to concentration of power in one individual or a special- the successful implementation of good corporate influence group through, for example, an independent governance practices at board level. To ensure the chairman, strong independent representation on the chairman acts in an independent manner, internationally board, and shareholder agreements specifying the recognised governance codes state that the chairman powers of controlling shareholders. -

CEO and Chairman: Are Two Heads Better Than One?

® TONE POWERED BY at the TOP Providing senior management, boards of directors, and audit committees Issue 78 | August 2016 with concise information on governance-related topics. CEO and Chairman: Are Two Heads Better Than One? Perhaps not since the Great Depression have Proponents of a combined CEO-chairman position businesses faced such widespread negative say the arrangement can provide significant benefits, perceptions. Displays of fraud, greed, and salary such as a clear line of command, continuity of disparities between the C-suite and the rank leadership, efficiency, enhanced knowledge of the and file have caused the public to react with company’s operations applied to board discussions, disappointment and distrust, with calls growing and the authority to quickly put board decisions for greater transparency and more effective into action. corporate governance. Indeed, many companies favor the arrangement. Discussions of corporate governance, no matter how According to the Spencer Stuart index on far-ranging, often end up at the same place — the board effectiveness, 52 percent of companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500 had a dual CEO- boardroom. Increasingly, the debate centers on chairman in 2015. And shareholders may be leadership structure and how power is appropriately benefitting, at least in the short term: Research balanced. And, in some cases, the issue comes published by Paul Hodgson, senior research down to who is sitting in the chief executive officer’s office, versus at the head of the table of the board of directors. Many are questioning whether the CEO should also serve as the chairman of the board, or should the two positions be separate. -

4.5 Report of the Chairman of the Supervisory

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 4 REPORT OF THE CHAIRMAN OF THE SUPERVISORY BOARD ON THE MEMBERSHIP OF THE SUPERVISORY BOARD, THE APPLICATION OF THE PRINCIPLE OF GENDER EQUALITY, THE SUPERVISORY BOARD’S PRACTICES AND THE COMPANY’S INTERNAL CONTROL AND RISK MANAGEMENT PROCEDURES 4.5 REPORT OF THE CHAIRMAN OF THE SUPERVISORY BOARD ON THE MEMBERSHIP OF THE SUPERVISORY BOARD, THE APPLICATION OF THE PRINCIPLE OF GENDER EQUALITY, THE SUPERVISORY BOARD’S PRACTICES AND THE COMPANY’S INTERNAL CONTROL AND RISK MANAGEMENT PROCEDURES To the shareholders, In my capacity as Chairman of the Supervisory Board, I hereby report to you on (i) the membership structure of the Board and the application of the principle of gender equality, (ii) the Supervisory Board’s practices during the year ended December 31, 2013 and (iii) the internal control and risk management procedures put in place by the Company. 4.5.1 MEMBERSHIP STRUCTURE OF THE SUPERVISORY BOARD, APPLICATION OF THE PRINCIPLE OF GENDER EQUALITY AND SUPERVISORY BOARD PRACTICES 4.5.1 a) Members – Board gender equality 4.5.1 b) Recent corporate governance In accordance with the applicable law and the Company’s bylaws, developments the Supervisory Board may have no less than 3 and no more than In conjunction with the Non-Managing General Partner (SAGES), 10 members, elected by the Annual Shareholders Meeting for a term Michelin’s Supervisory Board and Management have introduced a (1) of 4 years . All Supervisory Board members must be shareholders. continuous improvement process for the Group’s corporate governance According to the bylaws, no more than one-third of Supervisory practices, with a view to ensuring that these evolve in line with the Board members may be aged over 75. -

CAE INC. (The “Company”) CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER POSITION

CAE INC. (the “Company”) CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER POSITION DESCRIPTION GENERAL FUNCTION The President and Chief Executive Officer (“CEO”) has the primary responsibility for the leadership, strategic and management direction and business results of the Company. Working closely with the Board of Directors of the Company (the “Board”) and the management team, the CEO ensures that the Company establishes appropriate goals, and manages its resources to meet these goals. MAJOR RESPONSIBILITIES 1. Fiduciary Duties The CEO shall act as a Director and officer of the Company in the best interests of the Company with honesty and good faith towards its shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers, and the communities within which the Company operates. As the leading executive officer, the CEO assumes ultimate accountability for the development and execution of the Company’s strategy and policies. The CEO shall use such personal and professional skills in the role of Chief Executive, together with such contacts, experience and judgment as the CEO may possess with integrity and independence to optimise both the short-term and the long-term financial performance of the Company. The CEO shall play a full part in enabling the Board to arrive at balanced and objective decisions in the performance of its agreed role and functions. The CEO shall ensure that the objectives of the Company, as agreed by the Board, are fully, promptly and properly carried out. The CEO shall ensure that the financial and other decisions of the Board are fully, promptly and properly carried out. 2. Leadership The CEO exercises an appropriate level of leadership for the organization, manages the culture and builds a team atmosphere.