A Practical Handbook on the Pharmacovigilance of Antimalarial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descriptive Statistics (Part 2): Interpreting Study Results

Statistical Notes II Descriptive statistics (Part 2): Interpreting study results A Cook and A Sheikh he previous paper in this series looked at ‘baseline’. Investigations of treatment effects can be descriptive statistics, showing how to use and made in similar fashion by comparisons of disease T interpret fundamental measures such as the probability in treated and untreated patients. mean and standard deviation. Here we continue with descriptive statistics, looking at measures more The relative risk (RR), also sometimes known as specific to medical research. We start by defining the risk ratio, compares the risk of exposed and risk and odds, the two basic measures of disease unexposed subjects, while the odds ratio (OR) probability. Then we show how the effect of a disease compares odds. A relative risk or odds ratio greater risk factor, or a treatment, can be measured using the than one indicates an exposure to be harmful, while relative risk or the odds ratio. Finally we discuss the a value less than one indicates a protective effect. ‘number needed to treat’, a measure derived from the RR = 1.2 means exposed people are 20% more likely relative risk, which has gained popularity because of to be diseased, RR = 1.4 means 40% more likely. its clinical usefulness. Examples from the literature OR = 1.2 means that the odds of disease is 20% higher are used to illustrate important concepts. in exposed people. RISK AND ODDS Among workers at factory two (‘exposed’ workers) The probability of an individual becoming diseased the risk is 13 / 116 = 0.11, compared to an ‘unexposed’ is the risk. -

Risk Factors Associated with Maternal Age and Other Parameters in Assisted Reproductive Technologies - a Brief Review

Available online at www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library Advances in Applied Science Research, 2017, 8(2):15-19 ISSN : 0976-8610 CODEN (USA): AASRFC Risk Factors Associated with Maternal Age and Other Parameters in Assisted Reproductive Technologies - A Brief Review Shanza Ghafoor* and Nadia Zeeshan Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, University of Gujrat, Hafiz Hayat Campus, Gujrat, Punjab, Pakistan ABSTRACT Assisted reproductive technology is advancing at fast pace. Increased use of ART (Assisted reproductive technology) is due to changing living standards which involve increased educational and career demand, higher rate of infertility due to poor lifestyle and child conceivement after second marriage. This study gives an overview that how advancing age affects maternal and neonatal outcomes in ART (Assisted reproductive technology). Also it illustrates how other factor like obesity and twin pregnancies complicates the scenario. The studies find an increased rate of preterm birth .gestational hypertension, cesarean delivery chances, high density plasma, Preeclampsia and fetal death at advanced age. The study also shows the combinatorial effects of mother age with number of embryos along with number of good quality embryos which are transferred in ART (Assisted reproductive technology). In advanced age women high clinical and multiple pregnancy rate is achieved by increasing the number along with quality of embryos. Keywords: Reproductive techniques, Fertility, Lifestyle, Preterm delivery, Obesity, Infertility INTRODUCTION Assisted reproductive technology actually involves group of treatments which are used to achieve pregnancy when patients are suffering from issues like infertility or subfertility. The treatments can involve invitro fertilization [IVF], intracytoplasmic sperm injection [ICSI], embryo transfer, egg donation, sperm donation, cryopreservation, etc., [1]. -

Clarifying Questions About “Risk Factors”: Predictors Versus Explanation C

Schooling and Jones Emerg Themes Epidemiol (2018) 15:10 Emerging Themes in https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-018-0080-z Epidemiology ANALYTIC PERSPECTIVE Open Access Clarifying questions about “risk factors”: predictors versus explanation C. Mary Schooling1,2* and Heidi E. Jones1 Abstract Background: In biomedical research much efort is thought to be wasted. Recommendations for improvement have largely focused on processes and procedures. Here, we additionally suggest less ambiguity concerning the questions addressed. Methods: We clarify the distinction between two confated concepts, prediction and explanation, both encom- passed by the term “risk factor”, and give methods and presentation appropriate for each. Results: Risk prediction studies use statistical techniques to generate contextually specifc data-driven models requiring a representative sample that identify people at risk of health conditions efciently (target populations for interventions). Risk prediction studies do not necessarily include causes (targets of intervention), but may include cheap and easy to measure surrogates or biomarkers of causes. Explanatory studies, ideally embedded within an informative model of reality, assess the role of causal factors which if targeted for interventions, are likely to improve outcomes. Predictive models allow identifcation of people or populations at elevated disease risk enabling targeting of proven interventions acting on causal factors. Explanatory models allow identifcation of causal factors to target across populations to prevent disease. Conclusion: Ensuring a clear match of question to methods and interpretation will reduce research waste due to misinterpretation. Keywords: Risk factor, Predictor, Cause, Statistical inference, Scientifc inference, Confounding, Selection bias Introduction (2) assessing causality. Tese are two fundamentally dif- Biomedical research has reached a crisis where much ferent questions, concerning two diferent concepts, i.e., research efort is thought to be wasted [1]. -

Drug Safety in Translational Paediatric Research: Practical Points to Consider for Paediatric Safety Profiling and Protocol Development: a Scoping Review

pharmaceutics Review Drug Safety in Translational Paediatric Research: Practical Points to Consider for Paediatric Safety Profiling and Protocol Development: A Scoping Review Beate Aurich 1 and Evelyne Jacqz-Aigrain 1,2,* 1 Department of Pharmacology, Saint-Louis Hospital, 75010 Paris, France; [email protected] 2 Paris University, 75010 Paris, France * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Translational paediatric drug development includes the exchange between basic, clinical and population-based research to improve the health of children. This includes the assessment of treatment related risks and their management. The objectives of this scoping review were to search and summarise the literature for practical guidance on how to establish a paediatric safety specification and its integration into a paediatric protocol. PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and websites of regulatory authorities and learned societies were searched (up to 31 December 2020). Retrieved citations were screened and full texts reviewed where applicable. A total of 3480 publica- tions were retrieved. No article was identified providing practical guidance. An introduction to the practical aspects of paediatric safety profiling and protocol development is provided by combining health authority and learned society guidelines with the specifics of paediatric research. The paedi- atric safety specification informs paediatric protocol development by, for example, highlighting the Citation: Aurich, B.; Jacqz-Aigrain, E. need for a pharmacokinetic study prior to a paediatric trial. It also informs safety related protocol Drug Safety in Translational Paediatric Research: Practical Points sections such as exclusion criteria, safety monitoring and risk management. In conclusion, safety to Consider for Paediatric Safety related protocol sections require an understanding of the paediatric safety specification. -

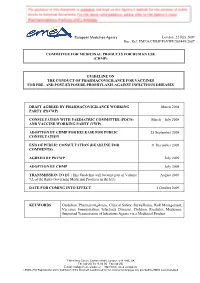

Guideline on the Conduct of Pharmacovigilance for Vaccines for Pre- and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Against Infectious Diseases

European Medicines Agency London, 22 July 2009 Doc. Ref. EMEA/CHMP/PhVWP/503449/2007 COMMITTEE FOR MEDICINAL PRODUCTS FOR HUMAN USE (CHMP) GUIDELINE ON THE CONDUCT OF PHARMACOVIGILANCE FOR VACCINES FOR PRE- AND POST-EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS AGAINST INFECTIOUS DISEASES DRAFT AGREED BY PHARMACOVIGILANCE WORKING March 2008 PARTY (PhVWP) CONSULTATION WITH PAEDIATRIC COMMITTEE (PDCO) March – July 2008 AND VACCINE WORKING PARTY (VWP) ADOPTION BY CHMP FOR RELEASE FOR PUBLIC 25 September 2008 CONSULTATION END OF PUBLIC CONSULTATION (DEADLINE FOR 31 December 2008 COMMENTS) AGREED BY PhVWP July 2009 ADOPTION BY CHMP July 2009 TRANSMISSION TO EC (This Guideline will become part of Volume August 2009 9A of the Rules Governing Medicinal Products in the EU). DATE FOR COMING INTO EFFECT 1 October 2009 KEYWORDS Guideline, Pharmacovigilance, Clinical Safety, Surveillance, Risk Management, Vaccines, Immunisation, Infectious Diseases, Children, Paediatric Medicines, Suspected Transmission of Infectious Agents via a Medicinal Product 7 Westferry Circus, Canary Wharf, London, E14 4HB, UK Tel. (44-20) 74 18 84 00 Fax (44-20) E-mail: [email protected] http://www.emea.europa.eu ©EMEA 2009 Reproduction and/or distribution of this document is authorised for non commercial purposes only provided the EMEA is acknowledged GUIDELINE ON THE CONDUCT OF PHARMACOVIGILANCE FOR VACCINES FOR PRE- AND POST-EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS AGAINST INFECTIOUS DISEASES TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY_______________________________________________________ 3 1. Introduction ____________________________________________________________ -

Eurartesim, INN-Piperaquine & INN-Artenimol

ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Eurartesim 160 mg/20 mg film-coated tablets. 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each film-coated tablet contains 160 mg piperaquine tetraphosphate (as the tetrahydrate; PQP) and 20 mg artenimol. For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Film-coated tablet (tablet). White oblong biconvex film-coated tablet (dimension 11.5x5.5mm / thickness 4.4mm) with a break-line and marked on one side with the letters “S” and “T”. The tablet can be divided into equal doses. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Eurartesim is indicated for the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in adults, adolescents, children and infants 6 months and over and weighing 5 kg or more. Consideration should be given to official guidance on the appropriate use of antimalarial medicinal products, including information on the prevalence of resistance to artenimol/piperaquine in the geographical region where the infection was acquired (see section 4.4). 4.2 Posology and method of administration Posology Eurartesim should be administered over three consecutive days for a total of three doses taken at the same time each day. 2 Dosing should be based on body weight as shown in the table below. Body weight Daily dose (mg) Tablet strength and number of tablets per dose (kg) PQP Artenimol 5 to <7 80 10 ½ x 160 mg / 20 mg tablet 7 to <13 160 20 1 x 160 mg / 20 mg tablet 13 to <24 320 40 1 x 320 mg / 40 mg tablet 24 to <36 640 80 2 x 320 mg / 40 mg tablets 36 to <75 960 120 3 x 320 mg / 40 mg tablets > 75* 1,280 160 4 x 320 mg / 40 mg tablets * see section 5.1 If a patient vomits within 30 minutes of taking Eurartesim, the whole dose should be re-administered; if a patient vomits within 30-60 minutes, half the dose should be re-administered. -

Taking Artemisinin to Clinical Anticancer Applications: Design, Synthesis and Characterization

Taking Artemisinin to Clinical Anticancer Applications: Design, Synthesis and Characterization of pH-responsive Artemisinin Dimer Derivatives in Lipid Nanoparticles Yitong Zhang A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Tomikazu Sasaki, Chair Rodney J.Y. Ho Champak Chatterjee Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Chemistry i ©Copyright 2015 Yitong Zhang ii University of Washington Abstract Taking Artemisinin to Clinical Anticancer Applications: Design, Synthesis and Characterization of pH-responsive Artemisinin Dimer Derivatives in Lipid Nanoparticles Yitong Zhang Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Tomikazu Sasaki Chemistry iii Abstract Qinghaosu or Artemisinin is an active sesquiterpene lactone isolated from Artemisia annua L. The natural product and its derivatives are known as a first line treatment for malaria. Investigations have also reported that the compound exhibits anti-cancer activities both on cell lines and in animal models. The remarkably stable endoperoxide bridge under ambient conditions is believed to be responsible for the selectivity as well as potency against cells that are rich in iron content. Dimeric derivatives where two artemisinin units are covalently bonded through lactone carbon (C10) show superior efficacies against both malaria parasites and cancer cells. Artemisinin dimer succinate derivative demonstrates a 100-fold enhancement in potency, compared to the natural product, with IC50 values in the low micromolar range. This work focuses on the development of artemisinin dimer derivatives to facilitate their clinical development. Novel pH-responsive artemisinin dimers were synthesized to enhance the aqueous solubility of the pharmacophore motif. Compounds with promising potency against human breast cancer cell lines were selected for lipid and protein based nanoparticle formulations for delivery of the derivatives without the need of organic co-solvents into animal models. -

Guidance for Industry E2E Pharmacovigilance Planning

Guidance for Industry E2E Pharmacovigilance Planning U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) April 2005 ICH Guidance for Industry E2E Pharmacovigilance Planning Additional copies are available from: Office of Training and Communication Division of Drug Information, HFD-240 Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Food and Drug Administration 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 (Tel) 301-827-4573 http://www.fda.gov/cder/guidance/index.htm Office of Communication, Training and Manufacturers Assistance, HFM-40 Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research Food and Drug Administration 1401 Rockville Pike, Rockville, MD 20852-1448 http://www.fda.gov/cber/guidelines.htm. (Tel) Voice Information System at 800-835-4709 or 301-827-1800 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) April 2005 ICH Contains Nonbinding Recommendations TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION (1, 1.1) ................................................................................................... 1 A. Background (1.2) ..................................................................................................................2 B. Scope of the Guidance (1.3)...................................................................................................2 II. SAFETY SPECIFICATION (2) ..................................................................................... -

Despite Improvements, COVID-19'S Health Care Disruptions Persist

News & Analysis Global Health More Comprehensive Care Drug-Resistant Malaria Detected for Miscarriage Needed Worldwide in Africa Will Require Monitoring About 1 in 10 women will have a miscar- Evidence in Africa that the malaria parasite riage over a lifetime—a statistic that repre- Plasmodium falciparum has developed sents 23 million pregnancies lost annually, genetic variants that confer partial resis- or 44 per minute worldwide, according to tance to the antimalarial drug artemisinin is a series of articles in The Lancet. Despite a warning of potential treatment failure on the magnitude, the articles described mis- the horizon, a drug-resistance monitoring carriage as a misunderstood phenomenon study suggested. and called for more comprehensive care to Partial resistance to artemisinin, the cur- prevent and treat miscarriage. rent frontline treatment for malaria, first The 15% of pregnancies that end in a emerged in Cambodia in 2008 and has be- miscarriage can be attributed to risk fac- come common in Southeast Asia, the au- tors including age during pregnancy, smok- thors wrote. Artemisinin is a fast-acting drug ing, stress, air pollution, and exposure to that typically clears the parasite within 3 pesticides, 1 of the studies reported. For days. It’s usually combined with a longer- Miscarriage is a misunderstood phenomenon, repeated miscarriages, which affect about acting drug to kill any remaining parasites. according to a recent series of articles. 2% of women, another study indicated When artemisinin resistance emerged in that progesterone could increase live-birth Asia, resistance to the combination therapy rates and that levothyroxine may decrease soon followed. 2020 when half of essential services had the risk of miscarriage for women with The current study was part of routine been interrupted. -

NINDS Custom Collection II

ACACETIN ACEBUTOLOL HYDROCHLORIDE ACECLIDINE HYDROCHLORIDE ACEMETACIN ACETAMINOPHEN ACETAMINOSALOL ACETANILIDE ACETARSOL ACETAZOLAMIDE ACETOHYDROXAMIC ACID ACETRIAZOIC ACID ACETYL TYROSINE ETHYL ESTER ACETYLCARNITINE ACETYLCHOLINE ACETYLCYSTEINE ACETYLGLUCOSAMINE ACETYLGLUTAMIC ACID ACETYL-L-LEUCINE ACETYLPHENYLALANINE ACETYLSEROTONIN ACETYLTRYPTOPHAN ACEXAMIC ACID ACIVICIN ACLACINOMYCIN A1 ACONITINE ACRIFLAVINIUM HYDROCHLORIDE ACRISORCIN ACTINONIN ACYCLOVIR ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE ADENOSINE ADRENALINE BITARTRATE AESCULIN AJMALINE AKLAVINE HYDROCHLORIDE ALANYL-dl-LEUCINE ALANYL-dl-PHENYLALANINE ALAPROCLATE ALBENDAZOLE ALBUTEROL ALEXIDINE HYDROCHLORIDE ALLANTOIN ALLOPURINOL ALMOTRIPTAN ALOIN ALPRENOLOL ALTRETAMINE ALVERINE CITRATE AMANTADINE HYDROCHLORIDE AMBROXOL HYDROCHLORIDE AMCINONIDE AMIKACIN SULFATE AMILORIDE HYDROCHLORIDE 3-AMINOBENZAMIDE gamma-AMINOBUTYRIC ACID AMINOCAPROIC ACID N- (2-AMINOETHYL)-4-CHLOROBENZAMIDE (RO-16-6491) AMINOGLUTETHIMIDE AMINOHIPPURIC ACID AMINOHYDROXYBUTYRIC ACID AMINOLEVULINIC ACID HYDROCHLORIDE AMINOPHENAZONE 3-AMINOPROPANESULPHONIC ACID AMINOPYRIDINE 9-AMINO-1,2,3,4-TETRAHYDROACRIDINE HYDROCHLORIDE AMINOTHIAZOLE AMIODARONE HYDROCHLORIDE AMIPRILOSE AMITRIPTYLINE HYDROCHLORIDE AMLODIPINE BESYLATE AMODIAQUINE DIHYDROCHLORIDE AMOXEPINE AMOXICILLIN AMPICILLIN SODIUM AMPROLIUM AMRINONE AMYGDALIN ANABASAMINE HYDROCHLORIDE ANABASINE HYDROCHLORIDE ANCITABINE HYDROCHLORIDE ANDROSTERONE SODIUM SULFATE ANIRACETAM ANISINDIONE ANISODAMINE ANISOMYCIN ANTAZOLINE PHOSPHATE ANTHRALIN ANTIMYCIN A (A1 shown) ANTIPYRINE APHYLLIC -

Ecological Impacts of Veterinary Pharmaceuticals: More Transparency – Better Protection of the Environment

Ecological Impacts of Veterinary Pharmaceuticals: More Transparency – Better Protection of the Environment Avoiding Environmental Pollution from Veterinary Pharmaceuticals To reduce the contamination of air, soil, and bodies of pharmaceuticals more stringently, monitoring systematically water caused by veterinary medicinal products used in their occurrence in the environment, converting animal hus- agriculture and livestock farming, effective measures bandry practices to preserve animals’ health with a minimal must be taken throughout the entire life cycle of these use of antibiotics, and enforcing legal regulations to ensure products – from production and authorisation to appli- implementation of all the measures outlined here. cation and disposal. In the context of the revision of veterinary medicinal products All stakeholders – whether they are farmers, veterinarians, legislation that is currently underway, this background paper consumers, or political decision makers – are called upon focuses on three measures that would contribute to mak- to contribute to reducing contamination of the environment ing information on the occurrence of veterinary drugs in the caused by pharmaceutical residues and to improving pro- environment and their eco-toxicological effects more widely tection of the environment and human health. Appropriate available and enhance protection of the environment from measures include establishing “clean” production plants, contamination with veterinary pharmaceuticals. developing pharmaceuticals with reduced environmental -

Why Do We Need a Social Psychiatry? Antonio Ventriglio, Susham Gupta and Dinesh Bhugra

The British Journal of Psychiatry (2016) 209, 1–2. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.175349 Editorial Why do we need a social psychiatry? Antonio Ventriglio, Susham Gupta and Dinesh Bhugra Summary interventions in psychiatry should be considered in the Human beings are social animals, and familial or social framework of social context where patients live and factors relationships can cause a variety of difficulties as well as they face on a daily basis. providing support in our social functioning. The traditional way of looking at mental illness has focused on abnormal Declaration of interest thoughts, actions and behaviours in response to internal D.B. is President of the World Psychiatric Association. causes (such as biological factors) as well as external ones such as social determinants and social stressors. We Copyright and usage contend that psychiatry is social. Mental illness and B The Royal College of Psychiatrists 2016. and difficulties at these levels can lead to psychopathological Antonio Ventriglio (pictured) is an honorary researcher at the Department of and behavioural dysfunctions. Social stressors can lead to changes Clinical and Experimental Medicine at the University of Foggia, Italy. Susham 5 Gupta is a consultant psychiatrist at the East London Mental Health in the cerebral structure and affect neuro-hormonal pathways. Foundation NHS Trust. Dinesh Bhugra is Emeritus Professor of Mental Health Even organic conditions such as dementia are said to be related to & Cultural Diversity at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, life events and social factors such as economic and educational status.5 King’s College London and is President of the World Psychiatric Association.