1 Finding Regina, Third Wave Feminism, and Regional Identity By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RICHARD FEREN 146B Rhodes Avenue – Toronto, on – M4L 3A1 416-787-0657 [email protected]

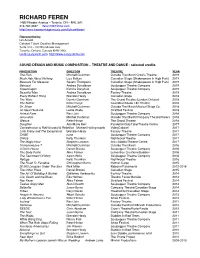

RICHARD FEREN 146B Rhodes Avenue – Toronto, ON – M4L 3A1 416-787-0657 [email protected] http://www.haemorrhage-music.com/richard-feren/ Represented by: Ian Arnold Catalyst Talent Creative Management Suite 310 - 100 Broadview Ave Toronto, Ontario Canada M4M 3H3 [email protected] http://www.catalysttcm.com SOUND DESIGN AND MUSIC COMPOSITION – THEATRE AND DANCE - selected credits PRODUCTION DIRECTOR THEATRE YEAR The Flick Mitchell Cushman Outside The March/Crow’s Theatre 2019 Much Ado About Nothing Liza Balkan Canadian Stage (Shakespeare In High Park) 2019 Measure For Measure Severn Thompson Canadian Stage (Shakespeare In High Park) 2019 Betrayal Andrea Donaldson Soulpepper Theatre Company 2019 Copenhagen Katrina Darychuk Soulpepper Theatre Company 2019 Beautiful Man Andrea Donaldson Factory Theatre 2019 Every Brilliant Thing Brendan Healy Canadian Stage 2018 The Wars Dennis Garnhum The Grand Theatre (London Ontario) 2018 The Nether Peter Pasyk Coal Mine/Studio 180 Theatre 2018 Dr. Silver Mitchell Cushman Outside The March/Musical Stage Co. 2018 An Ideal Husband Lezlie Wade Stratford Festival 2018 Animal Farm Ravi Jain Soulpepper Theatre Company 2018 Jerusalem Mitchel Cushman Outside The March/Company Theatre/Crow’s 2018 Silence Peter Hinton The Grand Theatre 2018 Daughter Ann-Marie Kerr Pandemic/QuipTake/Theatre Centre 2017 Confederation & Riel/Scandal & Rebellion Michael Hollingsworth VideoCabaret 2017 Little Pretty and The Exceptional Brendan Healy Factory Theatre 2017 CAGE none Soulpepper Theatre Company 2017 Unholy Kelly Thornton -

Rhubarb Festival

2020 22, – Festival sponsor FEBRUARY 12 FEBRUARY Buddies in Bad Times Theatre presents THE RHUBARB FESTIVAL Rhubarb2020-Brochure-V5.indd 1 2020-01-20 12:15 PM About Rhubarb Canada’s longest-running new works festival transforms Buddies into a hotbed of experimentation, with artists exploring new possibilities in theatre, dance, music, and performance art. Back this year for its 41st edition, Rhubarb is the place to see the most adventurous ideas in performance and to catch your favourite artists venturing into uncharted territory. Buddies in Bad Times Theatre is situated on the traditional lands of the Haudenosaunee, the Anishinaabe, and the Wendat, and the treaty territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit. We acknowledge them and any other Nations who care for the land (acknowledged and unacknowledged, recorded and unrecorded) as the past, present and future caretakers of this land, referred to as Tkaronto (“Where The Trees Meet The Water”; “The Gathering Place”). Buddies is honoured to be a home for queer, trans and 2-Spirit artists on these storied and sacred lands that have been stewarded by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years before the arrival of colonial settlers. Rhubarb2020-Brochure-V5.indd 2 2020-01-20 12:15 PM A Message from the Curatorial Collective An entire continent is on fire, Facebook’s immovable ad policy now determines truth in politics, and this country’s ongoing project of genocide continues. The inexorable truth of democracy? Progress comes slowly. But, this is Rhubarb. And for the 41st festival, we begin with an offering. Of and for the future. -

Buddies in Bad Times Announces Programming for 2016/17 Season

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, APRIL 19, 2016 Media Contact: Mark Aikman [email protected] 416.975.9130 x40 BUDDIES IN BAD TIMES ANNOUNCES PROGRAMMING FOR 2016/17 SEASON BUDDIESINBADTIMES.COM/SEASON – TICKETS ON SALE NOW TORONTO: April 19, 2016. Artistic Director Evalyn Parry announced an exciting line up for Buddies in Bad Times Theatre’s 2016/17 Season today. Parry’s first programmed season presents a series of engaging, timely productions that invite new conversations and perspectives onto Buddies stage. The season includes a queer spin on a hit improv comedy, the world premiere of a multidisciplinary project developed in the Buddies Residency Program, and a community-driven theatre project directed by Parry. The company also welcomes back a number of guest companies throughout the season. In announcing the season, Parry remarks: “I am thrilled to present a season that’s full of risky new creation, in conversation with classics of the modern stage. For me, queer theatre is about challenging form as well as content: finding new ways for our theatre to engage with and reflect our community. I look forward to inviting the community onto our stage – both literally and figuratively – this season.” Following sold out runs across North America, Rebecca Northan brings her hit show Blind Date to Buddies to kick off the mainstage season in September. Blind Date pairs a sexy clown with a willing audience member for a 90-minute, improvised show, starting with the titular blind date, then skillfully maneuvering through the evening in a “perfect marriage of theatre and comedy”. This re-imagined version of the play, being developed specifically for Buddies by Northan in collaboration with Evalyn Parry, explores queer romance for the first time. -

Black Boys House Program

Cover Image - Poster for Black Boys A BUDDIES IN BAD TIMES THEATRE PRODUCTION BLACK BOYS CREATED BY SAGA COLLECTIF STARRING BY STEPHEN JACKMAN-TORKOFF, TAWIAH BEN M’CARTHY + THOMAS OLAJIDE DIRECTED BY JONATHAN SEINEN Advertisement Image for Lulu v.7 Aspects of a Femme Fatale CHOREOGRAPHY BY VIRGILIA GRIFFITH On stage at Buddies May 1-30, 2018 DRAMATURGE BY MEL HAGUE SET + COSTUME DESIGN BY RACHEL FORBES SOUND + VIDEO DESIGN BY STEPHEN SURLIN LIGHTING DESIGN BY JARETH LI ASSISTANT CHOREOGRAPHER ARLEN AGUAYO-STEWART STAGE MANAGEMENT BY LAURA BAXTER TECHNICAL DIRECTOR BY ADRIEN WHAN COMMUNITY OUTREACH BY SEDINA FIATI Black Boys was developed in the Buddies Residency Program, sponsored by BMO Financial Group. CREATORS’ NOTE Saga Collectif was formed in 2012. We came together to create from an has provided necessary perspective, context and consideration, Virgilia experiential place, digging deeply into the lives of three young individuals and Jonathan have used their craft to realize our vision as fully as possible, to confront issues of race, sexuality, and gender through a complex and responding to the sensitivity of the subject matter. It was important to capture passionate exploration of Blackness and masculinity in raw and unapologetic each creator’s unique style and rhythm in our effort to liberate the Black terms. Using the safe space of the Black Boys project, we each challenged male body, acknowledging history and traumas while expressing the power ourselves to face the unknown to discover personal truths. In a climate of and beauty of the Black experience. Our goal was to bring Thomas, Tawiah continued violence against the Black male body and in a culture where artists and Stephen to the stage in a way that is risky, honest, and innovative, of colour are still severely underrepresented, Saga Collectif says, we are collectively imagining a healing Black narrative. -

Buddies in Bad Times Announces Its Queer Pride Programming

First published June 1; Revised June 17, 2020 Media Contact: Aidan Morishita-Miki [email protected] BUDDIES IN BAD TIMES ANNOUNCES ITS QUEER PRIDE PROGRAMMING JUNE 15-30, 2020 BUDDIESINBADTIMES.COM/PRIDE TORONTO: June 1, 2020. Buddies’ annual Queer Pride Festival celebrates our community’s unstoppable spirit, with digital and in-person (at a distance) offerings in performance, music, dance, and installation. And of course, a party, for good measure. With physical distancing measures still in place across the province, this year’s festival expands its footprint beyond the theatre’s home at 12 Alexander Street. Co-curated by Artistic Director Evalyn Parry and Metcalf Foundation Artistic Director Intern Daniel Carter, this year’s festival asks how, in a time of physical distancing, can we still find ways to take up space, be visible, out, loud, proud, and political? Parry and Carter comment: “In response to the pandemic, which has altered so many realities in such a short time, we have pivoted our annual Queer Pride Festival from a celebration where our communities gather at Buddies to one that brings the Buddies spirit out into our communities. The programming continues our proud tradition of provocative, genre-defying, and boundary-pushing performance, and the artists in this year's Festival have dreamed up new (as well as old-school) ways to forge connection across the distances between us, to celebrate our Queer Pride together this year like never before.” Offline, the theatre has spread its Pride programming well beyond its home in the Village. Following an open call for proposals, between June 15 and 28, over twenty artists create installations, pop-up performances, and mail-based projects, celebrating Pride at a hyper-local level. -

Jacob Zimmer Company Affiliations Process Design, Facilitation

Jacob Zimmer theatre maker, process designer, dramaturge, facilitator 848 Dovercourt Road Toronto Ontario, M6H 2X3, Canada p: 647-895-5025 e: [email protected] Born in Cape Breton and growing up in Halifax, Jacob now lives in Toronto and has worked across the country. He is the founding director of Small Wooden Shoe, and works as a dance dramaturge, teaches workshops, does talks, coaches, designs and facilitates meetings. company affiliations 2001- Small Wooden Shoe – Founding Director. a (mostly) theatre company bent on relieving alienation by proving that good ideas are entertaining and that pleasure and reflection require each other. smallwoodenshoe.org 2016- Intervene Design – Process designer and facilitator at a process design studio and consultancy. 2014- Banff Centre Peter Lougheed Leadership Institute – Faculty and designer. Designing and delivering programs for diverse groups of people working on difficult problems. 2005- Public Recordings/Ame Henderson – On-going dramaturgical collaboration with occasional forays into performing. 2008-14 Dancemakers – Dramaturge & Animateur. Full-time 2008-2011. Dancemakers is a contemporary dance company in Toronto. dancemakers.org 2005-9 Hub 14 – Co-director. Hub 14 is a performance and rehearsal studio in Toronto. hub14.org theatre conception/direction/co-creation (selected - all produced by Small Wooden Shoe unless noted) On-going The Fun Palace Radio Variety Show. Created and host. funpalce.ca 2014 Summer Spectacular. Conceived, directed, performed. Outdoor storytelling and giant puppet show. Toronto Fringe Festival. 2014/2012 Antigone Dead People by Evan Webber. Direction and concept. Protoype in Toronto and performed in Tokyo. 2012-13 Difficult Plays and Sings Simple Songs Conception/Direction. Various locations in Toronto. -

SG , DMI , MVHR : QG , CN , TH 1 in the Fall of 1980 Tennessee

D$+8 G$#*- S89 G$!7"+-, D)#$"! M)%I4'+, )#* -&" M)# $# -&" V)#%'/4"+ H'-"! R''2: Q/""+ G'(($6, C'22/#$-9 N)++)-$4", )#* T&")-+" H$(-'+91 This essay outlines how the gossip surrounding Tennessee Williams’s visit to Vancouver in 1980 has influenced the narratives of gay communi- ties and in so doing contributed to queer theatre history in Canada. Stories of Williams inviting young men to his hotel room and asking them to read from the Bible inspired Sky Gilbert and Daniel MacIvor to each write a play based on these events. The essay argues that Gilbert and MacIvor transcend the localized specificity of the initial rumours and deploy gossip as a tool to articulate a process of sexual and cultural marginalization, thereby fostering a dialogue with the past. This dialogue marks a crucial and pedagogical task in gay and queer theatre to address the on-going needs of an ever-changing community. Dans cet article, Dirk Gindt montre comment les rumeurs qui ont entouré la visite de Tennessee Williams à Vancouver en 1980 ont façonné les récits des communautés gais et, ce faisant, ont contribué à l’histoire du théâtre queer au Canada. Après avoir entendu dire que Williams avait invité des jeunes hommes à monter à sa chambre d’hôtel pour ensuite leur demander de lui lire des passages de la Bible, Sky Gilbert et Daniel MacIvor ont chacun été inspirés à écrire une pièce à partir de ces événements. Gindt fait valoir que Gilbert et MacIvor transcendent l’origine spécifique des premières rumeurs et les utilisent pour exprimer un processus de margina- lisation sexuelle et culturelle. -

The Climate Change Cycle: Reimagining the Footprint of Canadian Theatre

THE CLIMATE CHANGE CYCLE: REIMAGINING THE FOOTPRINT OF CANADIAN THEATRE A Report from Part 1: The Summit Co-Curated by Chantal Bilodeau and Sarah Garton Stanley Produced by the English Theatre Department at Canada's National Arts Centre with Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, the Canada Council for the Arts, The British Council and the Stratford Festival April 12-14, 2019 (Banff, Alberta, Canada) Report by Adrienne Wong, Chantal Bilodeau and Sarah Garton Stanley Report: January 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 2 Day One: Laying the Groundwork 4 Session 1 Sonali McDermid: Where Are We? 4 Session 2 Renee Lertzman: Relating with Reality – Walking Between Grief and Hope 5 Session 3 Alison Tickell: Sustainability in the Cultural Sector 8 Evening Session Cory Beaver in Conversation with Jenna Rodgers: Youth Climate Action 10 Day Two: What’s Happening Now? 12 Session 1 Clayton Thomas-Müller: Change the System, Not the Climate 12 Session 2 Kendra Fanconi: What an Artist Has Been Thinking About in Our Own Backyard 14 Session 3 Latai Taumoepeau: Refuge 15 Session 4 Ian Garrett: Digital Culture in the Face of Climate Change 17 Evening session Vicki Stroich: Bridges Between the Theatre World and the Environmental World 18 Day Three: Where to Now? 20 Closing Morning Session 20 CONCLUSION 23 Appendix A: A Note from Adrienne 24 Appendix B: The Summit Schedule 25 Appendix C: The Summit Inspirers 26 Appendix D: The Summit Participants 27 Appendix E: Biographies 29 Inspirers 29 Participants 32 Appendix F: Organizational Partners 39 1 INTRODUCTION The Climate Change Cycle is the third of a series of dramaturgically considered initiatives created by Sarah Garton Stanley, and undertaken by the English Theatre Department at Canada’s National Arts Centre (NAC). -

Buddies in Bad Times Announces Programming for 2017/18 Season

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, June 21, 2017 Media Contact: Aidan Morishita-Miki [email protected] 416.975.9130 x35 BUDDIES IN BAD TIMES ANNOUNCES PROGRAMMING FOR 2017/18 SEASON BUDDIESINBADTIMES.COM/SEASON – TICKETS ON SALE NOW TORONTO: June 21, 2017. Artistic Director Evalyn Parry announced an exciting line-up for Buddies in Bad Times Theatre’s 2017/18 season today. The season presents a series of engaging, timely productions that grapple with questions of race, indigeneity, sex, queerphobia, religion, and climate change. It includes a new multidisciplinary work co-created by Parry, a national tour of the 2016 hit Black Boys, and the premiere of a new work from the Buddies Residency Program, alongside several shows from guest companies. It is a season of partnerships and conversations, both new and ongoing, with theatre companies and artists at a local and national scale. The company also announced that the upcoming season will take place in a renovated facility. With support from the City of Toronto and the Department of Canadian Heritage’s Cultural Spaces Fund, Buddies’ home on Alexander Street will undergo important renovations over the next year including an improved cabaret space, accessibility upgrades, new seating, and soundproofing. In announcing the season, Parry remarks: “This season we implicate ourselves both in history and in our collective future. I’m excited to unveil significant new queer works on our stage, as well as welcoming back audience favourites from last season. I am also excited to be deepening our relationships with Toronto’s most groundbreaking indie companies, and establishing new and innovative partnerships with theatre makers here in Toronto and across the country.” The Buddies season opens in October with Kiinalik: These Sharp Tools, an exciting collaboration between Buddies artistic director Evalyn Parry and Inuk artist and Qaggiavuut artistic director Laakkulukk Williamson Bathory. -

Anne Made Me Gay: When Kindred Spirits Get Naked

Anne Made Me Gay: When Kindred Spirits Get Naked Rosemary Rowe Canadian Theatre Review, Volume 149, Winter 2012, pp. 6-11 (Article) Published by University of Toronto Press DOI: 10.1353/ctr.2012.0004 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/ctr/summary/v149/149.rowe.html Access Provided by Korea National Archives of the Arts at 01/11/13 3:06AM GMT Anne Made Me Gay: When Kindred Spirits Get Naked by Rosemary Rowe Do you get weak in the knees at the sight of gingham? Do you have an attraction to red-heads that you’ve never fully explored? Did Anne and her devotion to her bosom friends ... turn you gay? —Rowe, Anne Made Me Gay Call for Submissions It’s been over a hundred years since she burst onto the scene, and plucky red-headed heroine Anne Shirley still has a powerful hold on readers’ hearts the world over. Mark Twain called her ‘‘delightful.’’ Canadian literary greats like Margaret Atwood and Alice Munro acknowledge their affection for Anne. As I write this, the newly minted Duchess of Cambridge is visiting Anne’s adopted home, Prince Edward Island; she chose PEI as a stop on her first Canadian tour because she loved Anne as a girl and wanted to experience ‘‘something of a sentimental journey’’ (Haggarty). I grew up reading the Anne of Green Gables books, like any good Canadian girl. I remember the day my dad brought them to me. I was home from school with a fever and feeling pretty low. The first chapter was kind of hard to get into for a nine year old; it was mainly comprised of old people talking. -

Announcing Nightwood Theatre's 2019/20 SEASON

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 25th, 2019 Announcing Nightwood Theatre’s 2019/20 SEASON Celebrating 40 years of feminist theatre (Toronto)—Artistic Director Kelly Thornton and Managing Director Beth Brown are proud to announce Nightwood Theatre’s 2019/20 season. Marking our 40th year as Toronto’s preeminent feminist theatre company, we have curated an electric lineup of productions that bravely and playfully examine politics, privilege, power, and progress. Offering up three world premieres born out of creative collaboration from Common Boots Theatre, Aluna Theatre, and Nightwood’s own Write from the Hip program, as well as a Toronto premiere from Governor-General Award- nominated playwright, Karen Hines, Nightwood is proud to step into this landmark season with a focus on the future of contemporary Canadian theatre. Nightwood Theatre’s Artistic Director Kelly Thornton says: “I am thrilled to share the announcement of my last season of programming. After 18 years of leading this company and bringing provocative and compelling theatre to the stage, this our 40th anniversary season is a salute to our roots while putting a distinct focus on our future. The theatre of our foremothers was rooted in collective creation as well as challenging the status quo. Shared authorship is a common thread this year, as is work that experiments with form and pushes in content. Our 40th season is an array of work that grapples with our collective history, cautions us on the precarity of our present, and calls us to action for our future. I am humbled by the -

Canadian Women Director's Catalogue

The Canadian Women Director’s Catalogue A COMPREHENSIVE LIST OF WOMEN DIRECTING IN CANADA Copyright © 2011 Nightwood Theatre and the Professional Association of Canadian Theatres. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without written permission from the publishers. ISBN – 10: 0-921129-46-7 ISBN – 13: 978-0-921129-46-2 Nightwood Theatre 55 Mill Street, Suite 301 Case Goods Warehouse, Bldg. No. 74 Toronto ON Canada M5A 3C4 Professional Association of Canadian Theatres (PACT) 215 Spadina Ave, Suite 555 Toronto, ON M5T 2C7 Photo of Maggie Huculak, Gemma James-Smith, Dylan Smith, Sarah Dodd and Clare Coulter by Guntar Kravis Welcome I am so pleased to present to you with The Canadian Women Director’s Catalogue. In 2002, I co-spearheaded Equity in Canadian Theatre: the Women’s Initiative to examine the status of women in Canadian theatre. Over the last ten years Nightwood Theatre has partnered with the Playwrights Guild of Canada and the Professional Association of Canadian Theatres to continue research and advocacy for our country’s female practitioners. One of a number of disconcerting fi ndings, revealed the lack of female Artistic Directors at the country’s larger theatres. Yet another fi nding showed that those women who were Artistic Directors had better track records of hiring female playwrights and directors in their theatres. The solution seemed obvious: promote more women into AD positions across the country. But the monkey wrench, as I saw it, was that unless women had the opportunity to direct on the bigger stages they would never be considered “eligible” when those jobs came up.