Fingal, Jen Thesis Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rambo: Last Blood Production Notes

RAMBO: LAST BLOOD PRODUCTION NOTES RAMBO: LAST BLOOD LIONSGATE Official Site: Rambo.movie Publicity Materials: https://www.lionsgatepublicity.com/theatrical/rambo-last-blood Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Rambo/ Twitter: https://twitter.com/RamboMovie Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/rambomovie/ Hashtag: #Rambo Genre: Action Rating: R for strong graphic violence, grisly images, drug use and language U.S. Release Date: September 20, 2019 Running Time: 89 minutes Cast: Sylvester Stallone, Paz Vega, Sergio Peris-Mencheta, Adriana Barraza, Yvette Monreal, Genie Kim aka Yenah Han, Joaquin Cosio, and Oscar Jaenada Directed by: Adrian Grunberg Screenplay by: Matthew Cirulnick & Sylvester Stallone Story by: Dan Gordon and Sylvester Stallone Based on: The Character created by David Morrell Produced by: Avi Lerner, Kevin King Templeton, Yariv Lerner, Les Weldon SYNOPSIS: Almost four decades after he drew first blood, Sylvester Stallone is back as one of the greatest action heroes of all time, John Rambo. Now, Rambo must confront his past and unearth his ruthless combat skills to exact revenge in a final mission. A deadly journey of vengeance, RAMBO: LAST BLOOD marks the last chapter of the legendary series. Lionsgate presents, in association with Balboa Productions, Dadi Film (HK) Ltd. and Millennium Media, a Millennium Media, Balboa Productions and Templeton Media production, in association with Campbell Grobman Films. FRANCHISE SYNOPSIS: Since its debut nearly four decades ago, the Rambo series starring Sylvester Stallone has become one of the most iconic action-movie franchises of all time. An ex-Green Beret haunted by memories of Vietnam, the legendary fighting machine known as Rambo has freed POWs, rescued his commanding officer from the Soviets, and liberated missionaries in Myanmar. -

Drayton Entertainment Announces 2019 Season

Drayton Entertainment Announces 2019 Season Tuesday, September 11, 2018 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE – Drayton Entertainment will present a knockout playbill in 2019 packed with Broadway blockbusters, hilarious comedies, captivating dramas, stirring tributes and a number of fun‐filled family musicals and pantos. Artistic Director Alex Mustakas continues his bid to bring a wide variety of crowd‐pleasing productions to the award‐winning charitable not‐for‐profit theatre organization’s seven stages throughout Ontario. Drayton Entertainment has a history of being among the first outside of Broadway and the National Tour circuit to be granted the opportunity to produce highly sought‐after major musicals. The company was among the first professional regional theatres in North America to produce popular mega musicals like Disney’s Mary Poppins and Mamma Mia!. As part of the current 2018 Season, the company is producing the Canadian premieres of Ghost and Holiday Inn. The tradition continues in 2019. Drayton Entertainment will be among the first professional regional theatres in North America to produce the epic stage adaptation of Rocky: The Musical, based on the popular Sylvester Stallone film. The company will also produce the Canadian professional regional premieres of both Newsies and Priscilla, Queen of the Desert. Newsies is the exuberant Disney musical based on the true story of the Newsboysʹ strike of 1899. Priscilla, Queen of the Desert is the hit disco musical based on the Academy Award®‐winning film about three dazzling drag queens on a hilarious adventure across the Australian outback. This will be the first time the production has been produced professionally in Canada outside of the pre‐ Broadway run at Mirvish’s Princess of Wales Theatre in Toronto in 2010. -

Master Class Faculty

VIRTUAL MASTER CLASS FACULTY Sunday, January 24th VOICE | THEATER | BUSINESS SKILLS NANCY ANDERSON “Advice From a Pro” *please come with a song prepared and a recorded track. Students may have the opportunity to coach their song. Nancy Anderson is a 20-year veteran singer, actor and dancer of Broadway, Off-Broadway and regional stages. Last year Anderson understudied Glenn Close in the Broadway revival of “Sunset Boulevard” followed by a Helen Hayes nominated performance as Gladys in “The Pajama Game” at Arena Stage in Washington, D.C. She made her Broadway debut as Mona in “A Class Act,” played the roles of Helen and Eileen in the Broadway revival of “Wonderful Town” and starred as Lois/Bianca in the national tour and West End premiere of Michael Blakemore’s and Kathleen Marshall’s Broadway revival of “Kiss Me Kate,” for which she received Helen Hayes and Olivier Award nominations. Great Performances audiences are familiar with her London debut as Lois/Bianca, which was filmed for PBS in 2002 as well as her featured performance in the Carnegie Hall concert of “South Pacific” starring Reba McIntyre and Brian Stokes Mitchell. Other television appearances include Madame Secretary (The Middle Way, “Alice”) and PBS’s Broadway: The American Musical as the voice of Billie Burke. Anderson is a three-time Drama Desk Award Nominee; in 2000 for best supporting actress as eight female roles in Jolson & Co., in 2006 for best leading actress in Fanny Hill and in 2017 for Best Solo Performance in the one-woman musical “The Pen.” She has thrice been nominated for the Helen Hayes Award: in addition to last year’s “The Pajama Game,” she was also nominated for her role in “Side by Side by” Sondheim at Signature Theatre in 2011. -

Picture As Pdf

1 Cultural Daily Independent Voices, New Perspectives Relevant Soldier’s Play; Dated Bob and Carol David Sheward · Wednesday, February 5th, 2020 The twisted legacy of racism and shifting attitudes on sexuality are the diverse topics of two current New York stage offerings—a revival of A Soldier’s Play presented on Broadway by the Roundabout Theatre Company and a musical version of Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice produced by The New Group at the Pershing Square Signature Center Off-Broadway. Both present material from previous eras with stark perspectives on how relevant they may still be. While one is still shockingly immediate, the other seems quaint and laughable. What’s not too surprising is that race remains a hot- button issue while unabashed examinations of carnality have passed into the passe. Blair Underwood in A Soldier’s Play. Credit: Joan Marcus Charles Fuller’s A Soldier’s Play won the Pulitzer Prize in 1982 and searingly focuses on the corrosive effect of bigotry in the military and American society at large. After a hit Off-Broadway run presented by the Negro Ensemble Company, the suspense Cultural Daily - 1 / 5 - 03.08.2021 2 drama was adapted into a film called A Soldier’s Story, and then revived Off-Broadway in 2005. Fuller skillfully wraps his unflinching observations on racial animus and its poisonous influence into a taut murder mystery. In a 1944 training camp in the deep south, African-American officer Richard Davenport has been assigned to investigate the unsolved killing of career Army black sergeant Vernon Waters. At first, it appears white supremacists are the culprits since lynchings of African-American servicemen were not uncommon, but as Davenport delves deeper into the details of the case, he discovers a complex web of hate and resentment among the black soldiers fueled by institutional discrimination. -

Experience Technology Live INTERVITIS INTERFRUCTA HORTITECHNICA Innovations for Wine, Juice and Special Crops

MessageTRADE FAIRS | CONGRESSES | EVENTS 03 | 2016 Experience technology live INTERVITIS INTERFRUCTA HORTITECHNICA Innovations for wine, juice and special crops IT & Business Motek SEMF Showcases for For process competence – Mega techno party Industry and Office 4.0 against show event at Messe Stuttgart In the phrase „service partner“ there are two words that we are particularly fond of: „service“ and „partner“ CONTENTS NEWS – TRENDS 04 Major headway on construction Work on the Paul Horn Hall and on the West Entrance is proceeding at full steam 05 Editorial Digitisation as mega trend COVER STORY 08 Experience technology live INTERVITIS INTERFRUCTA HORTITECHNICA – Innovations for wine, juice and special crops LOCATION STUTTGART 14 Five stars for Stuttgart and its region Digitisation hotspot 18 17 Innovative region Stuttgart High Performance Computing Center Stuttgart (HLRS) TRADE FAIRS – MARKETS 18 VISION: The success story continues 20 IT & Business: Digitalised 4.0 processes live 24 Motek: For process competence – against show event 28 südback: Cross-selling – Making the cash tills ring twice Whether you want to hold a unique corporate event or you wish to have perfect lighting for your trade fair stand: we deploy our extensive know-how and high-quality MEDIA – PEOPLE equipment to develop tailor-made services perfectly shaped to your requirements. 44 Portrait: Stefanie Kromer, Communication What is more, we have been a partner of Messe Stuttgart for many years now and have an office 20 Coordinator at Messe Stuttgart right here on site. Our services cover the whole range of event needs in the fields of rigging and media technology – provided by a highly qualified team of professionals. -

2011 Kevin & Bean Clips Listed by Date

2011 Kevin & Bean clips listed by date January 03 Monday 01 Opening Segment-2011-01-03-No What It Do Nephew segment.mp3 02 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-03-6 am.mp3 03 Highlights Of Dick Clark and Ryan Seacrest-New Years Eve-2011-01-03.mp3 04 Harvey Levin-TMZ-2011-01-03.mp3 05 The Internet Round-up-2011-01-03.mp3 06 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-03-7 am.mp3 07 Thanks For That Info Bean-2011-01-03.mp3 08 Broken New Years Resolutions-2011-01-03.mp3 09 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-03-8 am.mp3 10 Eli Manning-2011-01-03-Turns 30 Today.mp3 11 Patton Oswalt-2011-01-03-New Book Out.mp3 12 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-03-9 am-Patton Oswalt Sits In.mp3 13 Dick Clark New Years Eve-More Highlights-2011-01-03-Patton Oswalt Sits In.mp3 14 Calling Arkansas About 2000 Dead Birds-2011-01-03-Patton Oswalt Sits In.mp3 15 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-03-10 am.mp3 January 04 Tuesday 01 Opening Segment-2011-01-04.mp3 02a Bean Did Not Realize It Was King Of Mexicos Birthday-2011-01-04.mp3 02b Show Biz Beat-2011-01-04-6 am.mp3 03 Calling Arkansas About 2000 Dead Birds-from Monday 2011-01-03-Patton Oswalt Sits In.mp3 04 and 14 Hotline To Heaven-2011-01-04-Michael Jackson.mp3 05 Oprah Rules In Kevins House-2011-01-04.mp3 06 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-04-7 am.mp3 07 Strange Addictions-2011-01-04-Listener Call-in.mp3 08 Paula Abdul-2011-01-04-On Her New TV Show.mp3 09 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-04-8 am.mp3 10 Bean Passed Out On Christmas Eve-2011-01-04-Wife Donna Explains.mp3 11 Psycho Body-2011-01-04.mp3 12 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-04-9 am.mp3 13 Afro Calls-2011-01-04.mp3 15 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-04-10 am.mp3 -

10Th Grade Monologue Packet

10th Grade Monologue Packet M - The Glass Menagerie: Tennessee Williams Tom 2 F - The Crucible: Arthur Miller A bigail (A) 2 F - The Crucible: Arthur Miller A bigail (B) 2 F - A View from the Bridge: A rthur Miller C atherine (A) 2 F - A View from the Bridge: A rthur Miller C atherine (B) 3 M - The Dark at the Top of the Stairs: W illiam Inge S ammy 3 F - N ight, Mother: Marsha Norman Jessie 3 F - A scension Day: Timothy Mason Faith 4 M/F - A unt Dan & Lemon: Wallace Shawn Lemon 4 F - Like Dreaming, Backwards: Kellie Powell N atalie 4 M - M ermaid in Miami: Wade Bradford E mperor Tropico 5 F - M y Fair Lady: Alan Jay Lerner E liza Doolittle 5 M - In Arabia We’d All Be Kings: S tephen Adly Guirgis C harlie 5 M - “Master Harold”…And the Boys: A thol Fugard H ally 6 M - S ammy Carducci’s Guide to Women: R onald Kidd S ammy 6 F - O ur Town: Thornton Wilder E mily 6 F - The Clean House: Sarah Ruhl Virginia 7 F - The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-In-The-Moon-Marigolds: Paul Zindel Tillie 7 M/F - Till We Meet Again: Colin and Mary Crowther U nknown 7 F - C harlene: Unknown C harlene 8 M/F - Irreconcilable Differences: Nancy Meyers and Charles Shyer C asey 8 F - Juno: Diablo Cody Juno 8 F - D irty Dancing: Eleanor Bergstein Frances 9 F - Felicity: J.J. -

617.872.8254 | Rebecca [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: October 16, 2019 Contact: Rebecca Curtiss 617.496.2000 x8841 | 617.872.8254 | [email protected] Creative Team and Cast Announced for American Repertory Theater Premiere of Moby-Dick New Collaboration Between Dave Malloy and Rachel Chavkin To Run December 3, 2019 – January 12, 2020 Download images here. Cambridge, MA – American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.) at Harvard University, under the leadership of Terrie and Bradley Bloom Artistic Director Diane Paulus and Executive Producer Diane Borger, have announced the creative team and cast of Moby-Dick, with music, lyrics, book, and orchestrations by Dave Malloy, developed with and directed by Rachel Chavkin. Performances of the new adaptation of Herman Melville’s classic novel begin Tuesday, December 3 at the Loeb Drama Center in Cambridge, MA. The production opens officially on Wednesday, December 11, 2019 and closes Sunday, January 12, 2020. “We are all in the belly of the whale…” From the creative team behind A.R.T.’s 2015 production of Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812 comes an epic musical adaptation of Herman Melville’s iconic American novel. As the egomaniacal Captain Ahab drives his crew across the seas in pursuit of the great white whale, Melville’s nineteenth-century vision of America collides head-on with the present. “I’ve always been fascinated with the surprising ways classic literature can resonate with contemporary times, and Moby-Dick is no exception,” says Malloy. “Melville was writing about America in 1851, as the country was struggling to define itself and reconcile all the conflicts that led inevitably to the Civil War; 170 years later, we’re still talking about the same issues— capitalism, democracy, environmentalism, race. -

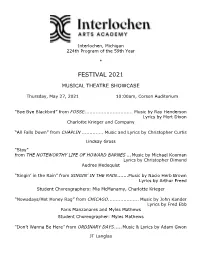

PDF Program Download

Interlochen, Michigan 224th Program of the 59th Year * FESTIVAL 2021 MUSICAL THEATRE SHOWCASE Thursday, May 27, 2021 10:00am, Corson Auditorium “Bye Bye Blackbird” from FOSSE ............................... Music by Ray Henderson Lyrics by Mort Dixon Charlotte Krieger and Company “All Falls Down” from CHAPLIN .............. Music and Lyrics by Christopher Curtis Lindsay Gross “Stay” from THE NOTEWORTHY LIFE OF HOWARD BARNES ... Music by Michael Kooman Lyrics by Christopher Dimond Audree Hedequist “Singin’ in the Rain” from SINGIN’ IN THE RAIN ....... Music by Nacio Herb Brown Lyrics by Arthur Freed Student Choreographers: Mia McManamy, Charlotte Krieger “Nowadays/Hot Honey Rag” from CHICAGO .................... Music by John Kander Lyrics by Fred Ebb Paris Manzanares and Myles Mathews Student Choreographer: Myles Mathews “Don’t Wanna Be Here” from ORDINARY DAYS ..... Music & Lyrics by Adam Gwon JT Langlas “No One Else” from NATASHA, PIERRE AND THE GREAT COMET OF 1812 ......... Music and Lyrics by Dave Malloy Mia McManamy “Run, Freedom, Run” from URINETOWN ...................... Music by Mark Hollmann Lyrics by Mark Hollmann and Greg Kotis Scout Carter and Company “Forget About the Boy” from THOROUGHLY MODERN MILLIE ........................... Music by Jeanine Tesori Lyrics by Dick Scanlan Hannah Bank and Company Student Choreographer: Nicole Pellegrin “She Used to Be Mine” from WAITRESS ........ Music and Lyrics by Sara Bareilles Caroline Bowers “Change” from A NEW BRAIN ......................... Music and Lyrics by William Finn Shea Grande “We Both Reached for the Gun” from CHICAGO .............. Music by John Kander Lyrics by Fred Ebb Theo Gyra and Company Student Choreographer: Myles Mathews “Love is an Open Door” from FROZEN ............ Music & Lyrics by Kristen Anderson-Lopez & Robert Lopez Charlotte Krieger and Daniel Rosales “Being Alive” from COMPANY ............... -

Playbill Jan

UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST FINE ARTS CENTER 2012 Center Series Playbill Jan. 31 - Feb. 22 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Skill.Smarts.Hardwork. That’s how you built your wealth. And that’s how we’ll manage it. The United Wealth Management Group is an independent team of skilled professionals with a single mission: to help their clients fulfill their financial goals. They understand the issues you face – and they can provide tailored solutions to meet your needs. To arrange a confidential discussion, contact Steven Daury, CerTifieD fiNANCiAl PlANNer™ Professional, today at 413-585-5100. 140 Main Street, Suite 400 • Northampton, MA 01060 413-585-5100 unitedwealthmanagementgroup.com tSecurities and Investment Advisory Services offered through NFP Securities, Inc., Member FINRA/SIPC. NFP Securities, Inc. is not affiliated with United Wealth Management Group. NOT FDIC INSURED • MAY LOSE VALUE • NOT A DEPOSIT• NO BANK GUARANTEE NO FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AGENCY GUARANTEES 10 4.875" x 3.75" UMASS FAC Playbill Skill.Smarts.Hardwork. That’s how you built your wealth. And that’s how we’ll manage it. The United Wealth Management Group is an independent team of skilled professionals with a single mission: to help their clients fulfill their financial goals. They understand the issues you face – and they can provide tailored solutions to meet your needs. To arrange a confidential discussion, contact Steven Daury, CerTifieD fiNANCiAl PlANNer™ Professional, today at 413-585-5100. 140 Main Street, Suite 400 • Northampton, MA 01060 413-585-5100 unitedwealthmanagementgroup.com tSecurities and Investment Advisory Services offered through NFP Securities, Inc., Member FINRA/SIPC. -

2020 SENIOR HONOREES Hommage À J.S

Welcome Susan D. Van Vorst Dean, Conservatory of Music Music Education: Andrew Buckley Major: Music Education Primary Instrument: Clarinet Presented by: Dr. Andrew Machamer 2020 SENIOR HONOREES Hommage à J.S. Bach Béla Kovács Music Therapy: Faith Hardy (b. 1937) Three Pieces for Clarinet Solo, Mvmt. 3 Igor Stravinsky Major: Music Therapy Primary Instrument: Saxophone (1882-1971) Presented by: Prof. Lalene Kay Presentation: The Road so Far Faith Hardy Music Theory: Evan Fraser Woodwind, Brass & Percussion: Nicholas Urbanic Major: Music Theory & Flute Performance Major: Music Education & Percussion Performance Primary Instrument: Flute Primary Instrument: Percussion Presented by: Dr. Jessica Narum Presented by: Prof. Josh Ryan Presentation: Making the Case for Asceses: Evan Fraser Pushing Forward Jamie Kunselman (BW ’16) A Comparative Study of the Unaccompanied I. Vacillation (b. 1993) Flute Works of André Jolivet II. Confrontation Composition: Daixuan Ai Major: Composition Voice: Kailyn Martino Primary Instrument: Piano Major: Voice Performance Presented by: Dr. Clint Needham Primary Instrument: Voice Presented by: Dr. JR Fralick Nocturne (Excerpt) Daixuan Ai (b. 1998) Apparition Claude Debussy (1862-1918) with Jason Aquila, piano HONOREE BIOGRAPHIES Arts Management: Bailey Ford Faith Hardy is a senior music therapy student who has been Major: Arts Management & Entrepreneurship involved on campus all four years. Throughout her undergraduate Presented by: Prof. Bryan Bowser career, she has participated in the Baldwin Wallace Marching Band where she held the position of Drum Major for two years Presentation Bailey Ford and President for one. She has also participated in the Pep Band during spring semesters. Within the Conservatory of Music, Faith has been an active member of the Cleveland Student Music Therapists where she currently holds the position of Secretary. -

'NIGHT, MOTHER by Marsha Norman Teacher Material

’Night, Mother by Marsha Norman Teacher Material ’NIGHT, MOTHER by Marsha Norman Teacher Material 1. Main Themes ........................................................................................................................ 2 2. Characters ............................................................................................................................. 2 3. About the author ................................................................................................................. 3 4. About the play ..................................................................................................................... 4 5. Reading ................................................................................................................................. 4 6. Possible Teaching Objectives.............................................................................................. 4 7. Dialogues for Discussion ..................................................................................................... 5 8. Assignments .......................................................................................................................... 9 9. Writing a Review................................................................................................................. 9 10. Vocabulary........................................................................................................................ 11 © by the Vienna theatre project Page 1 of 15 October 2002 ’Night, Mother by Marsha Norman Teacher