Excellence Through Inclusion New.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Its Review of Secondary Provision in Birkenhead and Bebington

APPENDIX C Independent assessment of the Wirral LA’s context and secondary review- What follows is my report and findings following my visits to the Wirral, and the next steps the LA should consider taking following : • its review of secondary provision in Birkenhead and Bebington • the successful delivery of 14-19 implementation which meets the needs of all its students in Birkenhead and Bebington, • the announcement in October 2007 that Birkenhead High School was to seek academy status, and above all • the implications for the local authority and its secondary schools of the recently announced National Challenge. Introduction: I would like to extend my warm thanks and appreciation to Councillor Phil Davies, Cabinet Member for Children’s Services and Lifelong Learning and to Howard Cooper, Director, Children’s and Young People’s Department, and his colleagues in the Local Authority and schools for the way in which they have helped me undertake my task on the Wirral. They have been welcoming, open and thoughtful in all my interviews and deliberations with them. I would also like to thank Frank Field MP for the time, help and support he and his research officer Patrick White have given me in undertaking this task, and Michael Clark, Diocesan Director, Shrewsbury Diocese, for his generous time to discuss issues, his background briefing and information. Most of all I would like to express my appreciation to the students from the Wirral schools that I met on my visits and the head teachers and staff that work with them to help raise their standards of achievement, their aspirations and ambitions. -

To Close Rock Ferry High School and Park High School on 31 August 2011 and Replace Both Schools with One Academy on 1 September

HAVE YOUR SAY ON SCHOOL CHANGES IN BIRKENHEAD About this document This document has been produced by Wirral Council as the first part of the consultation process with parents, the local community and other interested parties. The Council considers that the proposal is in the best interests of children, parents and staff at both Park High School and Rock Ferry High School and within the Birkenhead area as a whole. This proposal would bring together the two schools to create a single Academy to serve the Birkenhead area, increasing the opportunities for, and raising the performance of, all students in this area. The Governing Bodies at both schools have voted to support the development of an Academy in principle. The sponsors backing the Academy are as follows; . University of Chester (lead sponsor), . Birkenhead Sixth Form College (co-sponsor) . University of Liverpool (co-sponsor) . Wirral Metropolitan College (co-sponsor) . Wirral Council (also a co-sponsor) The Closure Consultation By law, Wirral Council as the local authority must consult on the closure of the two secondary schools separately from the consultation on the establishment of the new Academy, although the two consultations will take place around the same time. We would like to hear your views about the following proposal. The closure consultation will run until 7th April 2010. To close Rock Ferry High School and Park High School on 31 August 2011 and replace both schools with one Academy on 1 September 2011 ABOUT THE SCHOOLS running the academy. The Academy, working with the sponsors and other local partners, will provide a full range of courses to meet students’ academic and Rock Ferry High vocational aspirations. -

Birkenhead Academy PDF 157 KB

WIRRAL COUNCIL CABINET - 15th APRIL 2010 REVIEW OF SECONDARY SCHOOL PLACES: PROVISIONAL REPORT ON OUTCOME OF CONSULTATIONS ON PROPOSAL TO CLOSE ROCK FERRY HIGH SCHOOL AND PARK HIGH SCHOOL IN ORDER TO ESTABLISH AN ACADEMY Executive Summary This report advises the Cabinet of the provisional outcomes of the consultation process which has taken place in regard to the closure of the predecessor schools; Park High School and Rock Ferry School, as agreed at Cabinet on 14 th January 2010 as part of the Phase 1 Secondary Review. This report describes the responses, including additional suggestions put forward during the consultation process, and makes recommendations with regard to statutory proposals in this area. It does not cover separate consultations by the lead sponsor, the University of Chester, regarding the opening of an academy. These consultations end on 30 th April 2010. 1.0 Background 1.1 At its meeting of 29th November 2007, Cabinet instructed that Phase 1 of the Secondary Places Review should comprise schools in Birkenhead and Bebington (Wirral South). 1.2 On 6 th November 2008, Cabinet approved a consultation option for change comprising the closure of Park High and Rock Ferry High Schools in order to establish an Academy. 1.3 Following the announcement that Birkenhead High School for Girls would become a state-funded Academy, and further analysis of demographic trends, this option was altered to incorporate two Academies – a mixed Academy at the Park High site, and a Boys Academy on a site to be confirmed. This proposal was linked to the closure of three existing schools – Ridgeway High School, Rock Ferry High School and Park High School. -

Secondaryschoolspendinganaly

www.tutor2u.net Analysis of Resources Spend by School Total Spending Per Pupil Learning Learning ICT Learning Resources (not ICT Learning Resources (not School Resources ICT) Total Resources ICT) Total Pupils (FTE) £000 £000 £000 £/pupil £/pupil £/pupil 000 Swanlea School 651 482 1,133 £599.2 £443.9 £1,043.1 1,086 Staunton Community Sports College 234 192 426 £478.3 £393.6 £871.9 489 The Skinners' Company's School for Girls 143 324 468 £465.0 £1,053.5 £1,518.6 308 The Charter School 482 462 944 £444.6 £425.6 £870.2 1,085 PEMBEC High School 135 341 476 £441.8 £1,117.6 £1,559.4 305 Cumberland School 578 611 1,189 £430.9 £455.1 £885.9 1,342 St John Bosco Arts College 434 230 664 £420.0 £222.2 £642.2 1,034 Deansfield Community School, Specialists In Media Arts 258 430 688 £395.9 £660.4 £1,056.4 651 South Shields Community School 285 253 538 £361.9 £321.7 £683.6 787 Babington Community Technology College 268 290 558 £350.2 £378.9 £729.1 765 Queensbridge School 225 225 450 £344.3 £343.9 £688.2 654 Pent Valley Technology College 452 285 737 £339.2 £214.1 £553.3 1,332 Kemnal Technology College 366 110 477 £330.4 £99.6 £430.0 1,109 The Maplesden Noakes School 337 173 510 £326.5 £167.8 £494.3 1,032 The Folkestone School for Girls 325 309 635 £310.9 £295.4 £606.3 1,047 Abbot Beyne School 260 134 394 £305.9 £157.6 £463.6 851 South Bromsgrove Community High School 403 245 649 £303.8 £184.9 £488.8 1,327 George Green's School 338 757 1,096 £299.7 £670.7 £970.4 1,129 King Edward VI Camp Hill School for Boys 211 309 520 £297.0 £435.7 £732.7 709 Joseph -

Birkenhead Academy Appendix 5 PDF 92 KB

APPENDIX E2 Summary of responses by school People allied to Park High School Falling rolls • Understand rolls are falling and surplus places are high • Introduction of Birkenhead High School for Girls alongside Prenton has made the gender imbalance worse in mixed schools • Just because there are rooms with chairs in doesn’t mean there are surplus places • Standards cannot be sustained when rolls are falling Staff and Standards • Standards are improving year on year at both schools • Excellent ethos • Pupils have a good rapport with staff • Labelling both schools as National Challenge reinforces local snobbery against the schools • A very good school • Staff are very supportive and encouraging, give pupils best educational opportunities despite uncertainty • My child went to the Sanderling Unit and the teachers helped him a lot • Larger schools have worse GCSE results • Concerns that class sizes would rise • Concerns about loss of Sports specialism • Concerns about the impact of amalgamation on GCSE results • National Challenge is an arbitrary figure made up by Ed Balls • National Challenge does not take into account socioeconomic background or grammar schools • Last year 46% of pupils here passed English and 36% passed Maths • Science has gone from 25% to over 80% C or above • Park is not a failing school, it is unfair to staff to say so • School educates some extremely challenging students to achieve the best possible grades • Staff give up a lot of their time after school • Standards will improve because of staff, parents and ethos, -

Link Schools and Colleges (2013)

Link Schools and Colleges (2013) All Hallows School, Cheshire (now All Hallows Catholic College) Birchwood Community High School Birkenhead Sixth Form College Bishops Blue Coat School, Chester Blacon County High School Bridgewater High School (and Appleton 6th Form College), Warrington Cardinal Newman Catholic High School, Specialist College of Maths and Computing Carmel College Cheshire Oaks High School (now UCEA) Chester Catholic High School Culcheth High School, Warrington Deeside College, Deeside Ellesmere Port Catholic High School Ellesmere Port Specialist School of Performing Art (now UCEA) Great Sankey High School, Warrington Helsby High School King’s Grove School, a Specialist School for Business and Enterprise Lysander Community High School Macclesfield College Macclesfield High School, Arts and Technology College (now Macclesfield Academy) Malbank School and Sixth Form College Mid Cheshire College Middlewich High School Neston High School Park High School (now University Academy Birkenhead) Penketh County High School Pensby High School for Girls Pensby High School for Boys Priestley College Queens Park High School and Specialist Visual Arts College Reaseheath College, Nantwich Riverside College Halton Rock Ferry High School (now University Academy Birkenhead) Rudheath Community High School (now University of Chester Northwich) Rudheath High School (now University of Chester Northwich) Ruskin Sports and Languages College, Community High School Shorefields Technology College (now University Academy Liverpool) Sir John Deanes College -

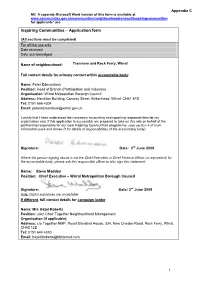

Inspiring Communities – Application Form

Appendix C NB. A separate Microsoft Word version of this form is available at www.communities.gov.uk/communities/neighbourhoodrenewal/inspiringcommunities for applicants’ use Inspiring Communities – Application form (All sections must be completed) For official use only Date received Date acknowledged Name of neighbourhood: Tranmere and Rock Ferry, Wirral Full contact details for primary contact within accountable body : Name: Peter Edmondson Position: Head of Branch (Participation and Inclusion) Organisation: Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council Address: Hamilton Building, Conway Street, Birkenhead, Wirral, CH41 4FD Tel: 0151 666 4304 Email: [email protected] I certify that I have understood the necessary accounting and reporting responsibilities for my organisation and, if this application is successful, am prepared to take on this role on behalf of the partnership responsible for our local Inspiring Communities programme. (see section 4 of main information pack and Annex D for details of responsibilities of the accountably body) Signature: Date: 3 rd June 2009 Where the person signing above is not the Chief Executive or Chief Finance Officer (or equivalent) for the accountable body, please ask this responsible officer to also sign this statement: Name: Steve Maddox Position: Chief Executive – Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council Signature: Date: 3 rd June 2009 Note: Digital signatures are acceptable If different , full contact details for campaign leader Name: Mrs Hazel Roberts Position: Joint Chair Together Neighbourhood Management Organisation (if applicable): Address: c/o Together NMP, Royal Standard House, 334, New Chester Road, Rock Ferry, Wirral, CH42 1LE Tel: 0151 644 4830 Email: [email protected] 1 SECTION 1: CONTACT INFORMATION AND INITIAL ELIGIBILITY 1A: Local authority name: Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council Neighbourhood must be within one of the eligible local authority areas listed in section 4 in the main information pack. -

CHESHIRE RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION COMMITTEE's REPORT Tenth Post-War Re.Port for the Year 1955/56 Committee

f t CHESHIRE RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION COMMITTEE'S REPORT Tenth Post-War Re.port for the Year 1955/56 Committee. Four Committee Met;tings were held during the year and the following is a record of attendances : A. S. CAIN (President) ....... ... ... .... 4 , N. J. O'NEILL (Bowdon) ... 4 R. D'ARcy NESBITT (~ast President) 0. J. E. STARK (Old Birkonians) 2 N. MCCAIG (Pas~ Presid~nt) 2 N. A. STEEL (Birkenhead Park) 4 J. MONTEDOR (V.ice-Pres~dent) 4 W. J. THOMPSON (OldCaldeians) .. 3 P. H. DAVIES (Vice~Presi~enS)3 .. ç 4 D. R. WYNN WILLIAMS (Hoylakë) .. 3 G. B. GETHING (Wllmslow) ... 3. E. J. LOAIlER (New Brighton) ... 4 W. G. HOWARD (Asst. Hon. Treasurer) ... 1 , KH. MILLS (Winnington Park) 4 H ..V. MIDDLETON (Asst. Hon. Secretary) 4 C. NODEN (Sale) 3 W. M. SHENNAN (Honorary Secretary) .,. 4 Mr. J. E. STARK joined the Committee after the second meeting in place of Mr. T. G. Smith. It is sad to record that Mr. R. D'ARcy NESBITT (Pat to aIl who knew him) passed away on the 2Dth April, 1956. A Past President it is indeed a severe 10ss to the County after a lifetime of service. ' The following is a list of clubs and schools affiliated with the County and Rugby Union: CLUBS. Ashton-on-Mersey.. Dukinfield. Old Rockferrians. Aisager College. , Hoylake. Old Salians. Bebington.. H.M.S. "Blackcap." Old Whitchurchians. Birkenhead Park ..- Isle of Man. Oldershaw Old Boys. Bowdon. Macclesfield. Oswestry & District. Capenhurst... Mirrlees. Port Sunlight. Chester.... New Brighton. R.A.F., West Kirby. Chester College. -

Institution Code Institution Title a and a Co, Nepal

Institution code Institution title 49957 A and A Co, Nepal 37428 A C E R, Manchester 48313 A C Wales Athens, Greece 12126 A M R T C ‐ Vi Form, London Se5 75186 A P V Baker, Peterborough 16538 A School Without Walls, Kensington 75106 A T S Community Employment, Kent 68404 A2z Management Ltd, Salford 48524 Aalborg University 45313 Aalen University of Applied Science 48604 Aalesund College, Norway 15144 Abacus College, Oxford 16106 Abacus Tutors, Brent 89618 Abbey C B S, Eire 14099 Abbey Christian Brothers Grammar Sc 16664 Abbey College, Cambridge 11214 Abbey College, Cambridgeshire 16307 Abbey College, Manchester 11733 Abbey College, Westminster 15779 Abbey College, Worcestershire 89420 Abbey Community College, Eire 89146 Abbey Community College, Ferrybank 89213 Abbey Community College, Rep 10291 Abbey Gate College, Cheshire 13487 Abbey Grange C of E High School Hum 13324 Abbey High School, Worcestershire 16288 Abbey School, Kent 10062 Abbey School, Reading 16425 Abbey Tutorial College, Birmingham 89357 Abbey Vocational School, Eire 12017 Abbey Wood School, Greenwich 13586 Abbeydale Grange School 16540 Abbeyfield School, Chippenham 26348 Abbeylands School, Surrey 12674 Abbot Beyne School, Burton 12694 Abbots Bromley School For Girls, St 25961 Abbot's Hill School, Hertfordshire 12243 Abbotsfield & Swakeleys Sixth Form, 12280 Abbotsfield School, Uxbridge 12732 Abbotsholme School, Staffordshire 10690 Abbs Cross School, Essex 89864 Abc Tuition Centre, Eire 37183 Abercynon Community Educ Centre, Wa 11716 Aberdare Boys School, Rhondda Cynon 10756 Aberdare College of Fe, Rhondda Cyn 10757 Aberdare Girls Comp School, Rhondda 79089 Aberdare Opportunity Shop, Wales 13655 Aberdeen College, Aberdeen 13656 Aberdeen Grammar School, Aberdeen Institution code Institution title 16291 Aberdeen Technical College, Aberdee 79931 Aberdeen Training Centre, Scotland 36576 Abergavenny Careers 26444 Abersychan Comprehensive School, To 26447 Abertillery Comprehensive School, B 95244 Aberystwyth Coll of F. -

Metropolitan Borough of Wirral Education And

METROPOLITAN BOROUGH OF WIRRAL EDUCATION AND LIFELONG LEARNING SELECT COMMITTEE 12 MARCH 2003 EXCELLENCE IN WIRRAL: ANNUAL REPORT, 2001 – 2002 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 This report sets out the successes in the second year of Excellence in Wirral, which has developed in complexity as the government’s policy for the Excellence in Cities initiative, and the rest of its diversity agenda, evolves. Funding has been guaranteed up to 2006, although the detail of the Spending Review will not be known until the Autumn. As a phase 2 Partnership, we expect to receive a primary roll-out, which will bring the 3 main strands (Gifted and Talented, Learning Mentors and Learning Support Units) into a small number of the most disadvantaged primary schools. No details are available as yet. The considerable resources allocated to Excellence in Cities are attached to highly structured programmes and challenging targets. The overall target of 52% grades A* - C at GCSE, with 53.8% of pupils achieving top GCSE grades for 2002, was exceeded. (See Appendix 1 for a full breakdown of Wirral and individual school targets for EiC.) 1.1 The DfES monitors the progress towards targets closely, as well as the progress and activity within the strands, in particular the Gifted and Talented strand, and Excellence Challenge. This annual report outlines the progress made and future priorities in each of the 8 strands, with a clear indication of both internal and external evaluation where relevant. It will be sent to the DfES, as well as forming part of local evaluation. The Select Committee is asked to note this report. -

Proposed Submission Draft Spatial Portrait 1 Introduction 2

Contents Core Strategy - Proposed Submission Draft Spatial Portrait 1 Introduction 2 2 Borough Profile 3 3 Settlement Area Profiles 27 4 Settlement Area 1 - Wallasey 29 5 Settlement Area 2 - Commercial Core 36 6 Settlement Area 3 - Birkenhead 50 7 Settlement Area 4 - Bromborough and Eastham 59 8 Settlement Area 5 - Mid Wirral 70 Created with Limehouse Software Publisher 9 Settlement Area 6 - Hoylake and West Kirby 77 10 Settlement Area 7 - Heswall 84 11 Settlement Area 8 - Rural Areas 90 12 Document List 100 13 Glossary 106 Core Strategy for Wirral - Proposed Submission Draft Spatial Portrait Core Strategy for Wirral - Proposed 2 Submission Draft Spatial Portrait 1 Introduction 1.1 This document is a working update of a Spatial Portrait for Wirral, which is intended to provide a more detailed description of the social, economic and Created with Limehouse Software Publisher environmental context of the Borough to accompany the publication of the Proposed Submission Draft Core Strategy for Wirral. 1.2 Earlier versions of the Portrait have been published on two previous occasions and made subject to public consultation, as part of the Spatial Options Report for the emerging Core Strategy in January 2010 and alongside the Preferred Options for the Core Strategy in November 2010. Some of the information included was also published as part of the separate public consultation on Draft Settlement Area Policies undertaken in January 2012(1). 1.3 This update takes account of many of the suggestions and comments received in response to previous consultation, as well as the findings of more up-to-date studies and evidence, where available. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Tuesday Volume 524 1 March 2011 No. 123 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 1 March 2011 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2011 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through The National Archives website at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/information-management/our-services/parliamentary-licence-information.htm Enquiries to The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 145 1 MARCH 2011 146 government boundaries, but ultimately they have to House of Commons deliver constituencies of more equal size. At the moment, constituencies can vary by over 50%, which is simply Tuesday 1 March 2011 not right. Recall of MPs The House met at half-past Two o’clock 2. Nadhim Zahawi (Stratford-on-Avon) (Con): What plans he has to introduce a power for electors in a PRAYERS constituency to recall their elected Member of Parliament. [42562] [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] 5. Chris Skidmore (Kingswood) (Con): What plans he has to introduce a power for electors in a constituency Oral Answers to Questions to recall their elected Member of Parliament. [42566] 7. Roberta Blackman-Woods (City of Durham) (Lab): DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER When he plans to publish his proposals to allow electors in a constituency to recall their elected Member of Parliament. [42568] The Deputy Prime Minister was asked— The Deputy Prime Minister (Mr Nick Clegg): The Parliamentary Constituencies Government are committed to bringing forward legislation to introduce a power to recall Members of Parliament. 1. Gavin Barwell (Croydon Central) (Con): What We are currently considering what would be the fairest, recent representations he has received on his proposals and most appropriate and robust, procedure, and we to create fewer and more equally sized constituencies.