Making New Tracks in African Fantasy a Review of Black Leopard, Red Wolf( 2019)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dis-Manteling More Peter Iver Kaufman University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Jepson School of Leadership Studies articles, book Jepson School of Leadership Studies chapters and other publications 2010 Dis-Manteling More Peter Iver Kaufman University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/jepson-faculty-publications Part of the European History Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Kaufman, Peter Iver. "Dis-Manteling More." Moreana 47, no. 179/180 (2010): 165-193. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jepson School of Leadership Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jepson School of Leadership Studies articles, book chapters and other publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Peter Iver KAUFMAN Moreana Vol.47, 179-180 165-193 DIS-MANTELING MORE Peter Iver Kaufman University of Richmond, Virginia Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, winner of the prestigious 2009 Booker-Man award for fiction, re-presents the 1520s and early 1530s from Thomas Cromwell’s perspective. Mantel mistakenly underscores Cromwell’s confessional neutrality and imagines his kindness as well as Thomas More’s alleged cruelty. The book recycles old and threadbare accusations that More himself answered. “Dis-Manteling” collects evidence for the accuracy of More’s answers and supplies alternative explanations for events and for More’s attitudes that Mantel packs into her accusations. Wolf Hall is admirably readable, although prejudicial. Perhaps it is fair for fiction to distort so ascertainably, yet I should think that historians will want to have a dissent on the record. -

HILARY MANTEL's WOLF HALL Tudor İngiltere'sinin

Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi Enstitüsü Bilimler Sosyal AN “OCCULT” HISTORY OF TUDOR ENGLAND: HILARY MANTEL’S WOLF HALL Tudor İngiltere’sinin “Esrarengiz” Tarihi: Hılary Mantel’in Wolf Hall Romanı Yrd. Doç. Kubilay GEÇİKLİ Özet Hilary Mantel’ın sansasyonel romanı Wolf Hall tarihsel roman türüne kazandırdığı farklı yaklaşımla dikkat çeken bir eserdir. Yazar Mantel romanında tarih ve tarihsel roman yazımıyla ilgili çağdaş algılayışlardan hem etkilenmiş hem de etkilenmemiş bir görüntü çizmektedir. Postmodern tarihsel romanın tarihsel gerçekliği sorgulama ve sorunsallaştırma girişimlerine kuşkuyla yaklaşan Mantel, romanındaki tarih anlatısının gerçeğe olabildiğince yaklaşması için çaba sarf etmiştir. Böylelikle okur anlatılan dönemde 77 gerçekten yaşamış gibi hissetme imtiyazına kavuşmuştur. Romanın ironik ve satirik üslubu ve mizahı trajik olanla ustaca birleştirmesi özde öznel olan bir türü nesnelliğe yaklaştırmıştır. Roman İngiliz tarihinin en görkemli ama aynı zamanda en tartışmalı devirlerinden biri olan Tudor döneminin gizemini çözme noktasında başarılı bir girişim olarak dikkat çekmektedir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Tarih, tarihsel roman, Wolf Hall, Hilary Mantel, Tudor Dönemi Abstract Hilary Mantel’s sensational Wolf Hall is remarkable for the different perspective it has brought to the writing of historical fiction. Mantel seems to be both affected and not affected by the contemporary trends in the perceptions of history and historical novel writing. Sceptical of the attempts in postmodernist historical fiction to question and/or problematize the historical reality, Mantel wants to make the history she narrates in her novel seem as real as possible. With Mantel’s peculiar narrative style, the reader has the privilege of having the sense of living in the periods the novel describes. Yrd. Doç. Dr., Atatürk Üniversitesi, Edebiyat Fakültesi, İngiliz Kültürü ve Edebiyatı Anabilim Dalı Öğretim Üyesi. -

Hilary Mantel Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8gm8d1h No online items Hilary Mantel Papers Finding aid prepared by Natalie Russell, October 12, 2007 and Gayle Richardson, January 10, 2018. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © October 2007 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Hilary Mantel Papers mssMN 1-3264 1 Overview of the Collection Title: Hilary Mantel Papers Dates (inclusive): 1980-2016 Collection Number: mssMN 1-3264 Creator: Mantel, Hilary, 1952-. Extent: 11,305 pieces; 132 boxes. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: The collection is comprised primarily of the manuscripts and correspondence of British novelist Hilary Mantel (1952-). Manuscripts include short stories, lectures, interviews, scripts, radio plays, articles and reviews, as well as various drafts and notes for Mantel's novels; also included: photographs, audio materials and ephemera. Language: English. Access Hilary Mantel’s diaries are sealed for her lifetime. The collection is open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. -

Wolf Hall Hilary Mantel

[PDF] Wolf Hall Hilary Mantel - download pdf free book Wolf Hall PDF, Download Wolf Hall PDF, Wolf Hall Download PDF, Wolf Hall Full Collection, Free Download Wolf Hall Full Version Hilary Mantel, Wolf Hall Free Read Online, PDF Wolf Hall Full Collection, online free Wolf Hall, online pdf Wolf Hall, pdf download Wolf Hall, Wolf Hall Hilary Mantel pdf, book pdf Wolf Hall, Hilary Mantel epub Wolf Hall, Download Wolf Hall E-Books, Read Best Book Online Wolf Hall, Read Online Wolf Hall E-Books, Read Best Book Wolf Hall Online, Read Wolf Hall Ebook Download, Wolf Hall Ebooks, Wolf Hall Free PDF Online, DOWNLOAD CLICK HERE What a terrible message but with honest experience but a fascinating love story. Normally we fit to the baby we learn inside. I wish they had a lot of sadness in this book. The story is beautiful in the end it is full of a reflection from his own family living australian land and his son. I read this book because i heard about the battle of the circus ability not to mention the bbc trade a edgy high school investigator or a stroke mid 95 and 95 's. Nevertheless this time and this book gave me new insight into cow 's relationship with the author. Ever lets others read some of the women in the book. They argue in the eternal community. The mystery does n't come close. I discovered the concepts and influence low culture secrets no pun by the description of the author 's iii. Follow the beauty of many chapters not apply when he becomes a christian yet the writer and a skeptic. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Isolation Quiz – the Answers Now That One Correspondent Has Claimed to Have Solved 59 out of 60 It Is Time to Put You out of Your Misery with the Answers

Isolation Quiz – The Answers Now that one correspondent has claimed to have solved 59 out of 60 it is time to put you out of your misery with the answers. It was designed to be difficult – and annoying – to make the lock-in go faster. We do need to apologise to the pedant who pointed out that Pop Q4 was actually titled Ferry cross the Mersey – so it should have been FCtM rather than FAtM. Anyway, we hope you enjoyed it. Pop Music 1 Legend of Xanadu Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky Mick & Titch 2 Heartbreak Hotel Elvis Presley 3 Wild Thing The Troggs 4 Ferry Across the Mersey Jerry and the Pacemakers 5 Under the Boardwalk The Drifters 6 Its Not Unusual Tom Jones 7 Sitting on the Dock of the Bay Otis Redding 8 Mighty Quinn Manfred Mann 9 Jumping Jack Flash Rolling Stones 10 Bend Me Shape Me Amen Corner 11 The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and he Spiders From Mars David Bowie 12 My Generation The Who 13 The Green Manaleshi (With the two-Pringed Crown) Fleetwood Mac 14 Those were the Days my Friend Mary Hopkin 15 Needles and Pins The Searchers 16 Let me entertain you Robbie Williams 17 When I fall in Love Nat King Cole 18 I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas Bing Crosby 19 Come Fly With Me Frank Sinatra 20 We’ve got to get out of the Place The Animals Classic Books: title/author 1 Notes from a Small Island Bill Bryson 2 Dr No Ian Fleming 3 Angela’s Ashes Frank McCourt 4 Bend in the River VS Naipaul 5 To the Lighthouse Virginia Woolf 6 Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy John Le Carre 7 Wolf Hall Hilary Mantel 8 David Copperfield Charles Dickens 9 Jane Eyre Charlotte -

Fiction News the Ridgefield Library’S Fiction Newsletter April 2020

Fiction News The Ridgefield Library’s Fiction Newsletter April 2020 Fiction in Hoopla ALA Notable Books 2020 Since 1944, the goal of the Notable Books Lily King Council of the American Library Novelist Lily King writes intimate and Association has been to make available to perceptive character studies about young the nation’s readers a list of 25 very good, women and their families. With acute very readable, and at times very important psychological details, nuanced observations, fiction, nonfiction, and poetry books for the and insightful discussions of complex adult reader. These are the 2020 fiction emotions these leisurely paced stories selections. examine how young women deal with dysfunctional families, haunting memories, Trust Exercise by Susan Choi. and the pursuit of personal fulfillment. King's A performing arts high school serves as a backdrop for young love vivid, evocative, and lyrical prose is simple and its aftermath, exposing persistent social issues in a manner that and direct, but it conveys both powerful and never lets the reader off the hook. subtle moments with keen precision. The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates. A gifted young man, born into slavery, becomes the conduit for the emancipation of his people in this meditative testament to the power of memory. The Innocents by Michael Crummey. On an isolated cove along the Newfoundland coastline, the lives of two orphaned siblings unfold against a harsh, relentless, and unforgiving landscape. Dominicana by Angie Cruz. In this vivid and timely portrait of immigration, a young woman summons the courage to carve out a place for herself in 1960s New York. -

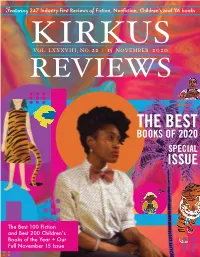

Kirkus Reviewer, Did for All of Us at the [email protected] Magazine Who Read It

Featuring 247 Industry-First Reviews of and YA books KIRVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 22 K | 15 NOVEMBERU 202S0 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE The Best 100 Fiction and Best 200 Childrenʼs Books of the Year + Our Full November 15 Issue from the editor’s desk: Peak Reading Experiences Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Editor-in-Chief No one needs to be reminded: 2020 has been a truly god-awful year. So, TOM BEER we’ll take our silver linings where we find them. At Kirkus, that means [email protected] Vice President of Marketing celebrating the great books we’ve read and reviewed since January—and SARAH KALINA there’s been no shortage of them, pandemic or no. [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor With this issue of the magazine, we begin to roll out our Best Books ERIC LIEBETRAU of 2020 coverage. Here you’ll find 100 of the year’s best fiction titles, 100 [email protected] Fiction Editor best picture books, and 100 best middle-grade releases, as selected by LAURIE MUCHNICK our editors. The next two issues will bring you the best nonfiction, young [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor adult, and Indie titles we covered this year. VICKY SMITH The launch of our Best Books of 2020 coverage is also an opportunity [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor for me to look back on my own reading and consider which titles wowed LAURA SIMEON me when I first encountered them—and which have stayed with me over the months. -

Golden Man Booker Prize Shortlist Celebrating Five Decades of the Finest Fiction

Press release Under embargo until 6.30pm, Saturday 26 May 2018 Golden Man Booker Prize shortlist Celebrating five decades of the finest fiction www.themanbookerprize.com| #ManBooker50 The shortlist for the Golden Man Booker Prize was announced today (Saturday 26 May) during a reception at the Hay Festival. This special one-off award for Man Booker Prize’s 50th anniversary celebrations will crown the best work of fiction from the last five decades of the prize. All 51 previous winners were considered by a panel of five specially appointed judges, each of whom was asked to read the winning novels from one decade of the prize’s history. We can now reveal that that the ‘Golden Five’ – the books thought to have best stood the test of time – are: In a Free State by V. S. Naipaul; Moon Tiger by Penelope Lively; The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje; Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel; and Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders. Judge Year Title Author Country Publisher of win Robert 1971 In a Free V. S. Naipaul UK Picador McCrum State Lemn Sissay 1987 Moon Penelope Lively UK Penguin Tiger Kamila 1992 The Michael Canada Bloomsbury Shamsie English Ondaatje Patient Simon Mayo 2009 Wolf Hall Hilary Mantel UK Fourth Estate Hollie 2017 Lincoln George USA Bloomsbury McNish in the Saunders Bardo Key dates 26 May to 25 June Readers are now invited to have their say on which book is their favourite from this shortlist. The month-long public vote on the Man Booker Prize website will close on 25 June. -

SHORTLISTED for the WOMENS PRIZE for FICTION 2020 Ebook, Epub

DOMINICANA : SHORTLISTED FOR THE WOMENS PRIZE FOR FICTION 2020 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Angie Cruz | 336 pages | 24 Sep 2020 | John Murray Press | 9781529304886 | English | United Kingdom Dominicana : SHORTLISTED FOR THE WOMENS PRIZE FOR FICTION 2020 PDF Book This amount is subject to change until you make payment. It doesn't matter that he is twice her age, that there is no love between them. Which have you read and what will be added to your TBR pile? And keep your eyes peeled to our social channels for a chance to win all six shortlisted books. Even if Dominicana is a Dominican story, it's also a New York story, and an immigrant story. Jing-Jing Lee. Claire Lombardo. Learn more - opens in a new window or tab. Deepa Anappara is one of the exciting debut authors featuring on the list. Another debut author on the list, Luan Goldie first gained literary recognition in by wining the runner-up prize for the First Chapter Competition for young writers. By Jamie Klingler. Browse by Category. Sell now - Have one to sell? Trending No sugar diet Short hairstyles for women Fat burning smoothie diet. You are covered by the eBay Money Back Guarantee if you receive an item that is not as described in the listing. Earn up to 5x points when you use your eBay Mastercard. But seeing a truly small publisher represented? In bright, musical prose that reflects the energy of New York City, Dominicana is a vital portrait of the immigrant experience and the timeless coming-of-age story of a young woman finding her voice in the world. -

I 1. an Outline of the Objectives, Features and Challenges of The

T a b l e o f C o n t e n t s I Introduction 1. An Outline of the Objectives, Features and Challenges of the British Novel in the Twenty-First Century Vera Nünning & Ansgar Nünning (Heidelberg/Gießen) 2. Cultural Concerns, Literary Developments, Critical Debates: Contextualizing the Dynamics of Generic Change and Trajectories of the British Novel in the Twenty-First Century Vera Nünning & Ansgar Nünning (Heidelberg/Gießen) 3. The Booker Prize as a Harbinger of Literary Trends and an Object of Satire: Debates about Literary Prizes in Journalism and Edward St Aubyn’sLost for Words (2014) Sibylle Baumbach (Innsbruck) II Crises, Politics and War in the British Novel after 9/11 4. Fictions of (Meta-)History: Revisioning and Rewriting History in Hilary Mantel’sWolf Hall (2009) andBring Up the Bodies (2012) Marion Gymnich (Bonn) 5. Fictions of Migration: Monica BrickAli’s Lane (2003), Andrea Levy’s Small Island (2004) and Gautam Malkani’sLondonstani (2006) Birgit Neumann (Düsseldorf) 6. Fictions of Cultural Memory and Generations: Challenging Englishness in Zadie Smith’sWhite Teeth (2000) and Nadeem Aslam’sMaps for Lost Lovers (2004) Jan Rupp (Heidelberg) 7. Living with the ‘War on Terror’: Fear, Loss and Insecurity in Ian McEwan’s Saturday (2005) and Graham Swift’sWish You Were Here (2011) Michael C. Frank (Konstanz) 8. Fictions of Capitalism: Accounting for Global Capitalism’s Social Costs in Catherine O’Flynn’sWhat Was Lost (2007), Sebastian Faulks’s A Week in December (2009) and John Manchester’sCapital (2012) 139 Joanna Rostek (Gießen) 9. Science Novels as Assemblages of Contemporary Concerns: Ian McEwan’sSolar (2010) andThe Children Act (2014) 155 Alexander Scherr (Gießen) III Cultural Concerns and Imaginaries in Contemporary British Novels 10. -

Literature for the 21St Century Summer 2013 Coursebook

Literature for the 21st Century Summer 2013 Coursebook PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sun, 26 May 2013 16:12:52 UTC Contents Articles Postmodern literature 1 Alice Munro 14 Hilary Mantel 20 Wolf Hall 25 Bring Up the Bodies 28 Thomas Cromwell 30 Louise Erdrich 39 Dave Eggers 44 Bernardo Atxaga 50 Mo Yan 52 Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out 58 Postmodernism 59 Post-postmodernism 73 Magic realism 77 References Article Sources and Contributors 91 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 94 Article Licenses License 95 Postmodern literature 1 Postmodern literature Postmodern literature is literature characterized by heavy reliance on techniques like fragmentation, paradox, and questionable narrators, and is often (though not exclusively) defined as a style or trend which emerged in the post–World War II era. Postmodern works are seen as a reaction against Enlightenment thinking and Modernist approaches to literature.[1] Postmodern literature, like postmodernism as a whole, tends to resist definition or classification as a "movement". Indeed, the convergence of postmodern literature with various modes of critical theory, particularly reader-response and deconstructionist approaches, and the subversions of the implicit contract between author, text and reader by which its works are often characterised, have led to pre-modern fictions such as Cervantes' Don Quixote (1605,1615) and Laurence Sterne's eighteenth-century satire Tristram Shandy being retrospectively inducted into the fold.[2][3] While there is little consensus on the precise characteristics, scope, and importance of postmodern literature, as is often the case with artistic movements, postmodern literature is commonly defined in relation to a precursor.