Chemical and Dynamical Processes in the Atmospheres of I. Ancient and Present-Day Earth II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants As Tracers of Planet Formation

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants as Tracers of Planet Formation Thesis by Marta Levesque Bryan In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California 2018 Defended May 1, 2018 ii © 2018 Marta Levesque Bryan ORCID: [0000-0002-6076-5967] All rights reserved iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I would like to thank Heather Knutson, who I had the great privilege of working with as my thesis advisor. Her encouragement, guidance, and perspective helped me navigate many a challenging problem, and my conversations with her were a consistent source of positivity and learning throughout my time at Caltech. I leave graduate school a better scientist and person for having her as a role model. Heather fostered a wonderfully positive and supportive environment for her students, giving us the space to explore and grow - I could not have asked for a better advisor or research experience. I would also like to thank Konstantin Batygin for enthusiastic and illuminating discussions that always left me more excited to explore the result at hand. Thank you as well to Dimitri Mawet for providing both expertise and contagious optimism for some of my latest direct imaging endeavors. Thank you to the rest of my thesis committee, namely Geoff Blake, Evan Kirby, and Chuck Steidel for their support, helpful conversations, and insightful questions. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to collaborate with Brendan Bowler. His talk at Caltech my second year of graduate school introduced me to an unexpected population of massive wide-separation planetary-mass companions, and lead to a long-running collaboration from which several of my thesis projects were born. -

Appendix 1 Some Astrophysical Reminders

Appendix 1 Some Astrophysical Reminders Marc Ollivier 1.1 A Physics and Astrophysics Overview 1.1.1 Star or Planet? Roughly speaking, we can say that the physics of stars and planets is mainly governed by their mass and thus by two effects: 1. Gravitation that tends to compress the object, thus releasing gravitational energy 2. Nuclear processes that start as the core temperature of the object increases The mass is thus a good parameter for classifying the different astrophysical objects, the adapted mass unit being the solar mass (written Ma). As the mass decreases, three categories of objects can be distinguished: ∼ 1. if M>0.08 Ma ( 80MJ where MJ is the Jupiter mass) the mass is sufficient and, as a consequence, the gravitational contraction in the core of the object is strong enough to start hydrogen fusion reactions. The object is then called a “star” and its radius is proportional to its mass. 2. If 0.013 Ma <M<0.08 Ma (13 MJ <M<80 MJ), the core temperature is not high enough for hydrogen fusion reactions, but does allow deuterium fu- sion reactions. The object is called a “brown dwarf” and its radius is inversely proportional to the cube root of its mass. 3. If M<0.013 Ma (M<13 MJ) the temperature a the center of the object does not permit any nuclear fusion reactions. The object is called a “planet”. In this category one distinguishes giant gaseous and telluric planets. This latter is not massive enough to accrete gas. The mass limit between giant and telluric planets is about 10 terrestrial masses. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

"High Accuracy Rotation--Vibration Calculations on Small Molecules" In

High Accuracy Rotation–Vibration Calculations on Small Molecules Jonathan Tennyson Department of Physics and Astronomy, University College London, London, UK 1 INTRODUCTION comprehensive understanding requires the knowledge of many millions, perhaps even billions, of individual transi- High-resolution spectroscopy measures the transitions bet- tions (Tennyson et al. 2007). It is not practical to measure ween energy levels with high accuracy; typically, uncer- this much data in the laboratory and therefore a more real- tainties are in the region of 1 part in 108. Although it is istic approach is the development of an accurate theoretical possible, under favorable circumstances, to obtain this sort model, benchmarked against experiment. of accuracy by fitting effective Hamiltonians to observed The incompleteness of most experimental datasets means spectra (see Bauder 2011: Fundamentals of Rotational that calculations are useful for computing other properties Spectroscopy, this handbook), such ultrahigh accuracy is that can be associated with spectra. The partition functions largely beyond the capabilities of purely ab initio proce- and the variety of thermodynamic properties that are linked dures. Given this, it is appropriate to address the question to this (Martin et al. 1991) are notable among these. Again, of why it is useful to calculate the spectra of molecules ab calculations are particularly useful for estimating these initio (Tennyson 1992). quantities at high temperature (e.g., Neale and Tennyson The concept of the potential energy surfaces, which in 1995). turn is based on the Born–Oppenheimer approximation, Other more fundamental reasons for calculating spectra underpins nearly all of gas-phase chemical physics. The include the search for unusual features, such as clustering of original motivation for calculating spectra was to provide energy levels (Jensen 2000) or quantum monodromy (Child stringent tests of potential energy surfaces. -

2. Molecular Stucture/Basic Spectroscopy the Electromagnetic Spectrum

2. Molecular stucture/Basic spectroscopy The electromagnetic spectrum Spectral region fooatocadr atomic and molecular spectroscopy E. Hecht (2nd Ed.) Optics, Addison-Wesley Publishing Company,1987 Per-Erik Bengtsson Spectral regions Mo lecu lar spec troscopy o ften dea ls w ith ra dia tion in the ultraviolet (UV), visible, and infrared (IR) spectltral reg ions. • The visible region is from 400 nm – 700 nm • The ultraviolet region is below 400 nm • The infrared region is above 700 nm. 400 nm 500 nm 600 nm 700 nm Spectroscopy: That part of science which uses emission and/or absorption of radiation to deduce atomic/molecular properties Per-Erik Bengtsson Some basics about spectroscopy E = Energy difference = c /c h = Planck's constant, 6.63 10-34 Js ergy nn = Frequency E hn = h/hc /l E = h = hc / c = Velocity of light, 3.0 108 m/s = Wavelength 0 Often the wave number, , is used to express energy. The unit is cm-1. = E / hc = 1/ Example The energy difference between two states in the OH-molecule is 35714 cm-1. Which wavelength is needed to excite the molecule? Answer = 1/ =35714 cm -1 = 1/ = 280 nm. Other ways of expressing this energy: E = hc/ = 656.5 10-19 J E / h = c/ = 9.7 1014 Hz Per-Erik Bengtsson Species in combustion Combustion involves a large number of species Atoms oxygen (O), hydrogen (H), etc. formed by dissociation at high temperatures Diatomic molecules nitrogen (N2), oxygen (O2) carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen (H2) nitr icoxide (NO), hy droxy l (OH), CH, e tc. -

2001 Astronomy Magazine Index

2001 Astronomy magazine index Subject index Chandra X-ray Observatory, telescope of, free-floating planets, 2:20, 22 12:76 A Christmas Star, 1:102 absolute visual magnitude, 1:86 cold dark matter, 3:24, 26 G active region 9393, 7:22 colors, of celestial objects, 9:82–83 Gagarin, Yuri, 4:36–41 Africa, observation from, 4:107–112, 10:48– Comet Borrelly, 9:33–37 galaxies 53 comets, 2:93 clusters of Andromeda Galaxy computers, accessing image archives with, in constellation Leo, 5:28 constellations of, 11:64–69 7:40–45 Massive Cluster Survey (MACS), consuming other galaxies, 12:25 corona of Sun, 1:24, 26 3:28 warp in disk of, 5:22 cosmic rays collisions of, 6:24 animal astronauts, 4:43–47 general information, 1:36–39 space between, 9:81 apparent visual magnitude, 1:86 origin of, 1:43–47 gamma ray bursts, 1:28, 30 Apus (constellation), 7:80–84 cosmology Ganymede (Jupiter's moon), 5:26 Aquila (constellation), 8:66–70 and particle physics, 6:39–43 Gemini Telescope, 2:26, 28 Ara (constellation), 7:80–84 unanswered questions, 6:46–52 Giodorno Bruno crater, 11:28, 30 Aries (constellation), 11:64–69 Gliese 876 (red dwarf star), 4:18 artwork, astronomical, 12:80–85 globular clusters, viewing, 8:72 asteroids D green stars, 3:82–85 around Zeta Leporis (star), 11:26 dark matter Groundhog Day, 2:96–97 cold, 3:24, 26 near Earth, 8:44–49 astronauts, animal as, 4:43–47 distribution of, 12:30, 32 astronomers, amateur, 10:88–89 whether exists, 8:26–31 H Hale Telescope, 9:46–53 astronomical models, 9:22, 24 deep sky objects, 7:87 HD 168443 (star), 4:18 Astronomy.com website, 1:78–84 Delphinus (constellation), 10:72–76 HD 82943 (star), 8:18 astrophotography DigitalSky Voice software, 8:65 HH 237 (meteor), 6:22 black holes, 1:26, 28 Dobson, John, 9:68–71 HR 1998 (star), 11:26 costs of basic equipment, 5:86 Dobsonian telescopes HST. -

The Rotational Spectrum of Protonated Sulfur Dioxide, HOSO+

A&A 533, L11 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201117753 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics Letter to the Editor The rotational spectrum of protonated sulfur dioxide, HOSO+ V. Lattanzi1,2, C. A. Gottlieb1,2, P. Thaddeus1,2, S. Thorwirth3, and M. C. McCarthy1,2 1 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden St., Cambridge, MA 02138, USA e-mail: [email protected] 2 School of Engineering & Applied Sciences, Harvard University, 29 Oxford St., Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 3 I. Physikalisches Institut, Universität zu Köln, Zülpicher Str. 77, 50937 Köln, Germany Received 21 July 2011 / Accepted 19 August 2011 ABSTRACT Aims. We report on the millimeter-wave rotational spectrum of protonated sulfur dioxide, HOSO+. Methods. Ten rotational transitions between 186 and 347 GHz have been measured to high accuracy in a negative glow discharge. Results. The present measurements improve the accuracy of the previously reported centimeter-wave spectrum by two orders of magnitude, allowing a frequency calculation of the principal transitions to about 4 km s−1 in equivalent radial velocity near 650 GHz, or one linewidth in hot cores and corinos. Conclusions. Owing to the high abundance of sulfur-bearing molecules in many galactic molecular sources, the HOSO+ ion is an excellent candidate for detection, especially in hot cores and corinos in which SO2 and several positive ions are prominent. Key words. ISM: molecules – radio lines: ISM – molecular processes – molecular data – line: identification 1. Introduction abundant in hot regions; (6) and radio observations of SH+ and SO+ (Menten et al. 2011; Turner 1994) have established that pos- Molecules with sulfur account for about 10% of the species iden- itive ions of sulfur-bearing molecules are surprisingly abundant tified in the interstellar gas and circumstellar envelopes. -

Search for Brown-Dwarf Companions of Stars⋆⋆⋆

A&A 525, A95 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201015427 & c ESO 2010 Astrophysics Search for brown-dwarf companions of stars, J. Sahlmann1,2, D. Ségransan1,D.Queloz1,S.Udry1,N.C.Santos3,4, M. Marmier1,M.Mayor1, D. Naef1,F.Pepe1, and S. Zucker5 1 Observatoire de Genève, Université de Genève, 51 Chemin des Maillettes, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland e-mail: [email protected] 2 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching bei München, Germany 3 Centro de Astrofísica, Universidade do Porto, Rua das Estrelas, 4150-762 Porto, Portugal 4 Departamento de Física e Astronomia, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade do Porto, Portugal 5 Department of Geophysics and Planetary Sciences, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 69978, Israel Received 19 July 2010 / Accepted 23 September 2010 ABSTRACT Context. The frequency of brown-dwarf companions in close orbit around Sun-like stars is low compared to the frequency of plane- tary and stellar companions. There is presently no comprehensive explanation of this lack of brown-dwarf companions. Aims. By combining the orbital solutions obtained from stellar radial-velocity curves and Hipparcos astrometric measurements, we attempt to determine the orbit inclinations and therefore the masses of the orbiting companions. By determining the masses of poten- tial brown-dwarf companions, we improve our knowledge of the companion mass-function. Methods. The radial-velocity solutions revealing potential brown-dwarf companions are obtained for stars from the CORALIE and HARPS planet-search surveys or from the literature. The best Keplerian fit to our radial-velocity measurements is found using the Levenberg-Marquardt method. -

Ijmp.Jor.Br V

INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT & PRODUCTION (IJM&P) http://www.ijmp.jor.br v. 10, n. 8, Special Edition Seng 2019 ISSN: 2236-269X DOI: 10.14807/ijmp.v10i8.1046 A NEW HYPOTHESIS ABOUT THE NUCLEAR HYDROGEN STRUCTURE Relly Victoria Virgil Petrescu IFToMM, Romania E-mail: [email protected] Raffaella Aversa University of Naples, Italy E-mail: [email protected] Antonio Apicella University of Naples, Italy E-mail: [email protected] Taher M. Abu-Lebdeh North Carolina A and T State Univesity, United States E-mail: [email protected] Florian Ion Tiberiu Petrescu IFToMM, Romania E-mail: [email protected] Submission: 5/3/2019 Accept: 5/20/2019 ABSTRACT In other papers already presented on the structure and dimensions of elemental hydrogen, the elementary particle dynamics was taken into account in order to be able to determine the size of the hydrogen. This new work, one comes back with a new dynamic hypothesis designed to fundamentally change again the dynamic particle size due to the impulse influence of the particle. Until now it has been assumed that the impulse of an elementary particle is equal to the mass of the particle multiplied by its velocity, but in reality, the impulse definition is different, which is derived from the translational kinetic energy in a rapport of its velocity. This produces an additional condensation of matter in its elemental form. Keywords: Particle structure; Impulse; Condensed matter. [http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/us/] Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States License 1749 INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT & PRODUCTION (IJM&P) http://www.ijmp.jor.br v. -

Chemical Formulas the Elements

Chemical Formulas A chemical formula gives the numbers and types of atoms that are found in a substance. When the substance is a discrete molecule, then the chemical formula is also its molecular formula. Fe (iron) is a chemical formula Fe2O3 is a molecular formula The Elements The chemical formulas of most of the elements are simply their elemental symbol: Na (sodium) Fe (iron) He (helium) U (uranium) These chemical formulas are said to be monatomic—only an atom in chemical formula 1 The Elements There are seven elements that occur naturally as diatomic molecules—molecules that contain two atoms: H2 (hydrogen) N2 (nitrogen) O2 (oxygen) F2 (fluorine) Cl2 (chlorine) Br2 (bromine) I2 (iodine) The last four elements in this list are in the same family of the Periodic Table Binary Compounds A binary compound is one composed of only two different types of atoms. Rules for binary compound formulas 1. Element to left in Periodic Table comes first except for hydrogen: KCl PCl3 Al2S3 Fe3O4 2 Binary Compounds 2. Hydrogen comes last unless other element is from group 16 or 17: LiH, NH3, B2H4, CH4 3. If both elements are from the same group, the lower element comes first: SiC, BrF3 Other Compounds For compounds with three or more elements that are not ionic, if it contains carbon, this comes first followed by hydrogen. Other elements are then listed in alphabetical order: C2H6O C4H9BrO CH3Cl C8H10N4O2 3 Other Compounds However, the preceding rule is often ignored when writing organic formulas (molecules containing carbon, hydrogen, and maybe other elements) in order to give a better idea of how the atoms are connected: C2H6O is the molecular formula for ethanol, but nobody ever writes it this way—instead the formula is written C2H5OH to indicate one H atom is connected to the O atom. -

Syllabus of Biochemistry (Hons.)

Syllabus of Biochemistry (Hons.) for SEM-I & SEM-II under CBCS (to be effective from Academic Year: 2017-18) The University of Burdwan Burdwan, West Bengal 1 1. Introduction The syllabus for Biochemistry at undergraduate level using the Choice Based Credit system has been framed in compliance with model syllabus given by UGC. The main objective of framing this new syllabus is to give the students a holistic understanding of the subject giving substantial weight age to both the core content and techniques used in Biochemistry. The ultimate goal of the syllabus is that the students at the end are able to secure a job. Keeping in mind and in tune with the changing nature of the subject, adequate emphasis has been given on new techniques of mapping and understanding of the subject. The syllabus has also been framed in such a way that the basic skills of subject are taught to the students, and everyone might not need to go for higher studies and the scope of securing a job after graduation will increase. It is essential that Biochemistry students select their general electives courses from Chemistry, Physics, Mathematics and/or any branch of Life Sciences disciplines. While the syllabus is in compliance with UGC model curriculum, it is necessary that Biochemistry students should learn “Basic Microbiology” as one of the core courses rather than as elective while. Course on “Concept of Genetics” has been moved to electives. Also, it is recommended that two elective courses namely Nutritional Biochemistry and Advanced Biochemistry may be made compulsory. 2 Type of Courses Number of Courses Course type Description B. -

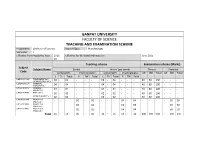

GANPAT UNIVERSITY FACULTY of SCIENCE TEACHING and EXAMINATION SCHEME Programme Bachelor of Science Branch/Spec

GANPAT UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF SCIENCE TEACHING AND EXAMINATION SCHEME Programme Bachelor of Science Branch/Spec. Microbiology Semester I Effective from Academic Year 2015- Effective for the batch Admitted in June 2015 16 Teaching scheme Examination scheme (Marks) Subject Subject Name Credit Hours (per week) Theory Practical Code Lecture(DT) Practical(Lab.) Lecture(DT) Practical(Lab.) CE SEE Total CE SEE Total L TU Total P TW Total L TU Total P TW Total UMBA101FOM FUNDAMENTALS 04 - 04 - - - 04 - 04 - - - 40 60 100 - - - OF MICROBIOLOGY UCHA101GCH GENERAL 04 - 04 - - - 04 - 04 - - - 40 60 100 - - - CHEMISTRY-I UPHA101GPH GENERAL 04 - 04 - - - 04 - 04 - - - 40 60 100 - - - PHYSICS-I UENA101ENG ENGLISH-I 02 - 02 - - - 02 - 02 - - - 40 60 100 - - - OPEN SUBJECT – 1 02 - 02 - - - 02 - 02 - - - 40 60 100 - - - UPMA101PRA PRACTICAL - - - 02 - 02 - - - 04 - 04 - - - - 50 50 MODULE-I UPCA101PRA PRACTICAL - - - 02 - 02 - - - 04 - 04 - - - - 50 50 MODULE-I UPPA101PRA PRACTICAL - - - 02 - 02 - - - 04 - 04 - - - - 50 50 MODULE-I Total 16 - 16 06 - 06 16 - 16 12 - 12 200 300 500 - 150 150 GANPAT UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF SCIENCE Programme Bachelor of Science Branch/Spec. Microbiology Semester I Version 1.0.1.0 Effective from Academic Year 2015-16 Effective for the batch Admitted in July 2015 Subject code UMBA 101 Subject Name FUNDAMENTALS OF MICROBIOLOGY FOM Teaching scheme Examination scheme (Marks) (Per week) Lecture(DT) Practical(Lab.) Total CE SEE Total L TU P TW Credit 04 -- -- -- 04 Theory 40 60 100 Hours 04 -- -- -- 04 Practical -- -- -- Pre-requisites: Students should have basic knowledge of Microorganisms and microscopy of 10+2 level. Learning Outcome: The course will help the student to understand basic fundamentals of Microbiology and history of Microbiology.