Public Petitions Committee: PE1531 Charitable Status of Independent Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directors' Report

Company No. SC008667 Charity No. SC012632 ST GEORGE’S SCHOOL FOR GIRLS (A Company Limited by Guarantee) DIRECTORS’ REPORT and ACCOUNTS For the year ended 31 July 2013 ST GEORGE’S SCHOOL FOR GIRLS (A Company Limited by Guarantee) REPORT OF THE DIRECTORS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 JULY 2013 The directors have pleasure in presenting their annual report for the year ended 31 July 2013 under the Companies Act 2006, the Charities and Trustee Investment (Scotland) Act 2005 (The Act) and the Charities Accounts (Scotland) Regulations 2006 (the Regulations), together with the audited financial statements for the year, and confirm that the latter comply with the requirements of the Companies Act 2006, the company’s Memorandum and Articles of Association and the Charities SORP 2005. REFERENCE & ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION St George’s School was founded in 1888. Its charity registration number is 12632 and company registration number is SC008667. It was incorporated in 1913 and the liability of each of its members is limited to £1 by guarantee. The Registered Office of the company is 61 Dublin Street, Edinburgh, EH3 6NL and the principal office is Garscube Terrace, Edinburgh, EH12 6BG. Directors The directors of the charitable company (“the charity”) are its trustees for the purpose of charity law and throughout this report are collectively referred to as the directors. The Hon Lord Woolman (Chairman) Mr P K Brewer (Vice Chairman) Sheriff L M Ruxton (Vice Chairman) Mr G T G Baird Mr G Donaldson Mr L S Duguid Dr E Duvall Dr E D A McCall Smith Mrs I C Miller -

The Mobility and Independence Needs of Children with a Visual Impairment

Steps to independence: the mobility and independence needs of children with a visual impairment Full research report September 2002 by Sue Pavey Graeme Douglas Steve McCall Mike McLinden Christine Arter VISUAL IMPAIRMENT CENTRE FOR TEACHING AND RESEARCH School of Education Edgbaston Birmingham B15 2TT Funded by: Contents Acknowledgements................................................................................iv Glossary................................................................................................. v Report overview ........................................................................1 Key recommendations.................................................................3 Introduction .............................................................................5 Background...........................................................................................5 Aims......................................................................................................6 Reporting protocol and key people.........................................................7 Methodology.......................................................................... 11 Research approach............................................................................... 11 Management group and advisory group ............................................... 11 Project timetable ................................................................................. 12 Summary of the data collection........................................................... -

Annual Review 2013

ANNUAL REVIEW 2013 Choice | Diversity | Excellence www.scis.org.uk Company limited by guarantee, registered in Scotland no 125368. Scottish Charity No SC018033 SCIS Governing Board 2013 CHAIRMAN Prof. Anton Colella BOARD MEMBERS Jennifer Alexander Business Director, George Heriot’s School, Edinburgh * Mark Becher Headmaster, The Compass School, Haddington ** Wendy Bellars Head, Queen Victoria School, Dunblane Gerry Brown Bursar, St Margaret’s School, Aberdeen ** Gavin Calder Headmaster, The Edinburgh Academy Junior School Colin Crosby Governor, Robert Gordon’s College, Aberdeen ** Gareth Edwards Principal, George Watson’s College, Edinburgh ^ Dr John Halliday Rector, High School of Dundee ** Alistair Hector Head, George Heriot’s School, Edinburgh ** Richard Hellewell Chief Executive, The Royal Blind School, Edinburgh Elizabeth Lister Governor, Strathallan School, Forgandenny Innes MacAskill Headmaster, Belhaven Hill School, Dunbar ** Janice MacNeill Principal & Chief Executive, Donaldson's School, Linlithgow ^ Tom McGhee Director, Spark of Genius, Paisley Colin Mair Rector, The High School of Glasgow ^ Jonathan Molloy Bursar, Erskine Stewart’s Melville Schools, Edinburgh * Simon Mills Headmaster, Lomond School, Helensburgh Armorel Robinson Bursar, Craigclowan Preparatory School, Perth * Gillian Stobo Principal, Craigholme School, Glasgow Kathleen Sweeney Bursar, St Aloysius’ College, Glasgow Richard Toley Head, Lathallan School, Angus Justin Wilkes Bursar, Dollar Academy, Clackmannanshire * Prof. Brian Williams Chair of Governors, Hutchesons’ -

Edinburgh Festivals Inspiring Creativity in Pupils

Edinburgh Festivals Inspiring Creativity in Pupils February 2020 i Credits Written and prepared by David Hicks Photo credits Theatre in Schools Scotland, Colin Hattersley 1 Contents Acknowledgements 3 Executive Summary 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Strategic context for Edinburgh schools 6 3. Overview of Festivals’ approaches 8 4. Schools Engagement Data 10 5. Festivals’ School Programmes 15 6. Case Studies by City Ward: Schools Engagement in 20 Festivals’ Programmes Appendix: Engagement Data by Edinburgh School 24 Figures/Tables Table 1: Number of Edinburgh schools engaged with the Festivals…………………………….. 10 Figure 1: Number of festivals’ school programmes by ward……………………………………….. 10 Figure 2: Pupil engagement by ward………………………………………………………………………….. 11 Table 2: Number of Programmes and Engagements at schools………………………………….. 11 Figure 3: Festivals’ school engagement mapped on Google Maps………………………………. 12 Figure 4: Percentage attendance at Festivals in 2018…………………………………………………. 12 Figure 5: Correlation between audience attendance and schools engagement…………… 13 2 Acknowledgements In the preparation of this report, Festivals Edinburgh gratefully acknowledges the advice and support of its eleven member festivals and the Platforms for Creative Excellence programme partners – Scottish Government, City of Edinburgh Council and Creative Scotland. Note on Methodology This report was prepared using data provided by each of the members of Festivals Edinburgh on their school programmes for the period January 2018 – May 2019, along with desktop research into the wider strategic context for Edinburgh schools. 3 Many festivals offering travel subsidy schemes to help with transport costs Executive Summary Programmes linked to the outcomes of the Curriculum for Excellence The aim of this study is to map the current schools activity of each of the Programmes promoting the goals of creative learning, inspiring creativity members of Festivals Edinburgh, providing insights to help inform the in pupils, developing curiosity, imagination, problem-solving, open- development of future programmes. -

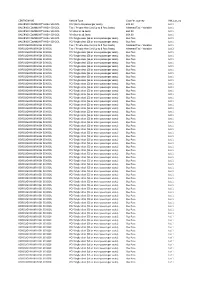

CENTRE NAME Vehicle Type Cost Per Journey

CENTRE NAME Vehicle Type Cost Per Journey AW_Lot_no BALERNO COMMUNITY HIGH SCHOOL PCV (36 to 55 passenger seats) £92.50 Lot 1 BALERNO COMMUNITY HIGH SCHOOL Taxi / Private Hire Car (Up to 8 Pass Seats) Metered Taxi - Variable Lot 1 BALERNO COMMUNITY HIGH SCHOOL MiniBus to 16 Seats £61.00 Lot 1 BALERNO COMMUNITY HIGH SCHOOL MiniBus to 16 Seats £64.90 Lot 1 BALERNO COMMUNITY HIGH SCHOOL PCV Single deck (56 or more passenger seats) Bus Pass Lot 1 BALERNO COMMUNITY HIGH SCHOOL PCV Single deck (56 or more passenger seats) Bus Pass Lot 1 BOROUGHMUIR HIGH SCHOOL Taxi / Private Hire Car (Up to 8 Pass Seats) Metered Taxi - Variable Lot 1 BOROUGHMUIR HIGH SCHOOL Taxi / Private Hire Car (Up to 8 Pass Seats) Metered Taxi - Variable Lot 2 BOROUGHMUIR HIGH SCHOOL PCV Single deck (56 or more passenger seats) Bus Pass Lot 1 BOROUGHMUIR HIGH SCHOOL PCV Single deck (56 or more passenger seats) Bus Pass Lot 1 BOROUGHMUIR HIGH SCHOOL PCV Single deck (56 or more passenger seats) Bus Pass Lot 1 BOROUGHMUIR HIGH SCHOOL PCV Single deck (56 or more passenger seats) Bus Pass Lot 1 BOROUGHMUIR HIGH SCHOOL PCV Single deck (56 or more passenger seats) Bus Pass Lot 1 BOROUGHMUIR HIGH SCHOOL PCV Single deck (56 or more passenger seats) Bus Pass Lot 1 BOROUGHMUIR HIGH SCHOOL PCV Single deck (56 or more passenger seats) Bus Pass Lot 1 BOROUGHMUIR HIGH SCHOOL PCV Single deck (56 or more passenger seats) Bus Pass Lot 1 BOROUGHMUIR HIGH SCHOOL PCV Single deck (56 or more passenger seats) Bus Pass Lot 1 BOROUGHMUIR HIGH SCHOOL PCV Single deck (56 or more passenger seats) Bus -

Visually-Impaired Musicians' Lives

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery 1 Perceptions of schooling, pedagogy and notation in the lives of visually-impaired musicians David Baker and Lucy Green Department of Culture, Communication and Media UCL Institute of Education, London Abstract This article discusses findings on schooling, pedagogy and notation in the life-experiences of amateur and professional visually-impaired musicians; and the professional experiences of sighted music teachers who work with visually-impaired learners. The study formed part of a broader UK Arts and Humanities Research Council funded project, officially entitled “Visually-impaired musicians’ lives: Trajectories of musical practice, participation and learning” (Grant ref. AH/K003291/1), but which came to be known as “Visually-Impaired Musicians’ Lives” (VIML) (see http://vimusicians.ioe.ac.uk). The project was led at the UCL Institute of Education, London, UK and supported by the Royal Academy of Music, London, and Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB) UK, starting in 2013 and concluding in 2015. It sourced “insider” perspectives from 219 adult blind and partially-sighted musicians, and 6 sighted music teachers, through life history interviews, in tandem with an international questionnaire, which collected quantitative and qualitative data. Through articulating a range of “insider” voices, this paper examines some issues, as construed by respondents, around educational equality and inclusion in music for visually-impaired children and adults in relation to three main areas: the provision of mainstream schooling versus special schools; pedagogy, including the preparedness of teachers to respond to the needs of visually-impaired learners; and the educational role of notation, focussing particularly on Braille as well as other print media. -

VISUAL IMPAIRMENT in SCOTLAND a Guide for Funders

VISUAL IMPAIRMENT IN SCOTLAND A guide for funders Katie Boswell and Angela Kail May 2016 VISUAL IMPAIRMENT IN SCOTLAND A guide for funders Katie Boswell and Angela Kail May 2016 NPC – Transforming the charity sector CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 3 Setting the scene ................................................................................................................................................ 3 The purpose of this report ................................................................................................................................... 3 The landscape of visual impairment in Scotland .................................................................... 4 Definitions and prevalence .................................................................................................................................. 4 Trends affecting visual impairment in Scotland ................................................................................................... 5 Priority needs ........................................................................................................................ 7 Priorities of people with visual impairment .......................................................................................................... 7 Priority solutions ...................................................................................................................12 Principles of good -

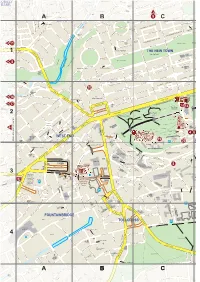

A 1 2 3 4 B C B C A

__ COMELY q//pg TTHH PAPARK MEL COMC LEA BANKBAN COME R ELYEL BAN LY M NKN BANK PL LY BAN ON K PL ACE M EWW DEAN P TH S A E RK G K ST MEWSME RARACE C EWS RO COMC EELYEL BANK TER ACA S L R P VE EE K ALLAN ST T COMELYELY BA N DEAN PA PA DEAN DEAN BE E BE COMECOOMELY BANK GROV LEARMONTHLEARMONLEAR PL D D DEAN PARK DEAN RACEC PARK DEAN FOR COMELY BANK TERRA FOR REET Bedford Street RAE COMEL RAE C COMELY BAN COMELY COMELY BAN COMELY D S S D D RK MEWS RK RK MEWS RK B HE URN PL ONTH BURN ST PL YNE ST TRE TRE ACE TH PL Y BANK AVEA S S ET ET TREE TREE A REET REET KKAVE CE K LEA K ROW RO T RMONT T VEITT DE CH'S SSQ H GARDENSGARDE LAN OW EENS L NUE BEDFORD E COURTCOUR A AEducationEducati Centre T NHAU T ion Centre E T HAMIL D DEAN PAR DEAN STRE TREET TON PLACE LEEAR ree DEAN HAUGH S MONTH GH GARD L EAR S ENS S I TR EET L V M T BERNAR TR S D'S EE E SOUTH K M K C S O R SOUT ES PLACE S R NTH G NTH C IE T M H LEARM E R IL EWS S N LESLLLE L ONTH G DEAN T B T S ARDARRD PARK MEWS ER NDE LALA LE ENENS N NEN LE A E A RD' SAU ST E R S C StockStocS Bridge STEPHEN P RE T AR RE ock Brid T Place D SCENT N S E CAR rid EEN cent N H Vin FETTES ROW MONTHM AVEN DUN DU DU DUN S L PPH St E M E W LEARMON S TTE T S St Stephen's TH TER SCENT LTO K S DAS ST DAS RACERACCCE LALANE ER Centre ST DAS CRE N R S 2.8M STREET ARK S TREETTRETR EN D BC US LAN R 11 DEAN P AN IRC E Stt Vincent R T C Vincnce STREET LANE EET RACE cent EET NE CUMBERLAND UE ChurchCCh NWW CUMBERLAND STREET LANE U ith LEARM BE ST STREE G E ONT AN TER N H TERR ANN STRE DE r of Le L A te O ACE CE a L E A W -

Annual Review 2016-17

ANNUAL REVIEW 2016-17 ANNUAL REVIEW 2016/17 CONTENTS PAGE 5 MANAGER’S REPORT 7 ACTIVE SCHOOLS STRUCTURE AND ACTIVE SCHOOLS TEAM 9 IMPACT 9 Participant sessions 9 Distinct participation 9 Activity sessions 10 YOUNG LEADERS 10 Young Ambassador programme 11 Young leader profile – Katie Hastie 12 PARTICIPATION 12 School Sport Award 13 Basketball 3 v 3, U14 league 13 Netball fun 5z 14 Dance 16 School spotlight – Broomhouse PS 17 EQUALITIES AND INCLUSION 17 Girls conference 19 Disability and Inclusion review 22 Inclusion lunchtime club initiative 23 COACHING, VOLUNTEERING AND OFFICIATING 23 Active Schools deliverers 24 Coach Education 25 Volunteering 26 EVENTS 26 Triathlon 26 Hub Autumn Games 28 Giant Heptathlon 28 Dance Extravaganza 29 ParaSport festival 30 Games @ the Hub 3 ANNUAL REVIEW 2016/17 4 ANNUAL REVIEW 2016/17 MANAGER’S REPORT by Jude Salmon I would like to start this year’s review with a quote from the Scottish Government (2013): ‘children who were more physically fit tended to have higher cognitive functions and academic achievement’ and ‘Physical activity has a significantly positive impact on children’s outcomes and academic achievements, with aerobic exercise producing the biggest impacts’ Scottish Government (2013), Health and wellbeing literature review – examining the links between health and wellbeing and educational outcomes, including attainment; Edinburgh; Scottish Government I believe Active Schools plays a large part, alongside the Edinburgh have now achieved a Gold Award and many many school staff, in ensuring every child is given an more received Silver and Bronze. We hope to continue to opportunity to take part in physical activity and sport at increase this number next year. -

Liberton / Gilmerton

LOCALITY SERVICE AREA SIZE OF SECTOR/CHALLENGES /ASPIRATIONS FOR SERVICE USERS SOUTH EAST/CENTRAL Total population: 124,930 Second largest population: 126,148 Age 0-15: 15,745 Largest proportion of persons aged 16 – 24 (40.3%) (students) Wards: Age: 65+ : 16,024 Highest concentration of people aged 85+ City Centre; Liberton / Health The only locality showing an increase (albeit small) in stroke-related mortality Gilmerton; Southside / Sharper decline in under 75 year old mortality rates than other localities Newington; Meadows / Morningside Health and Social Care Highest number of individuals in care homes (based on the person’s original home address) NEIGHBOURHOOD Lowest rate of unpaid carers provide 50+ hours per week (19.3%) PARTNERSHIPS (3) Highest number of people with Mental Health problems Other City Centre NP Largest percentage of households on low incomes (23.5%) South Central NP Low level of economic activity (57.5%) Highest percentage of students (20.9%) Liberton/Gilmerton NP Lowest percentage of retired people (9.6%) VSF General South Edinburgh VSF More than half of the city’s students Student numbers distort all indicators Highest private-rented City Centre VSF Low levels of social housing Most happy with Edinburgh Maintenance of the City Centre key for the city and the Council’s reputation Pockets of deprivation difficult to detect or address Continued growth in private rental may effect community cohesion Edinburgh Voluntary Organisations’ Council is a company limited by guarantee – No SC 173582 and is a registered Scottish charity No. SC 009944 Registered Office: 14 Ashley Place, Edinburgh EH6 5PX Edinburgh Voluntary Organisations’ Council is a company limited by guarantee – No SC 173582 and is a registered Scottish charity No. -

Directory of Independent Schools in Scotland 2015-2016

Choice | Diversity | Excellence Directory of Independent Schools in Scotland 2015-2016 Choice | Diversity | Excellence scis.org.uk 1 2 Choice | Diversity | Excellence scis.org.uk Contents About SCIS ............................................................................................................ 5 SCIS Information ................................................................................................. 6 Alphabetical List of Schools .........................................................................11 School Reference Map ....................................................................................12 Geographical List of Schools ........................................................................13 Reference table: Mainstream Schools .......................................................14 Mainstream Schools Profiles ........................................................................18 Complex Additional Support Needs Schools .........................................52 Reference table: Additional Support Needs Schools ..........................54 Additional Support Needs Schools Profiles ............................................55 Choice | Diversity | Excellence scis.org.uk 3 About SCIS Welcome to the 2015 -2016 edition of the SCIS directory of independent schools in Scotland. The Scottish Council of Independent Schools is an educational charity representing over 70 member schools, which educate more than 30,000 children of mixed abilities and backgrounds. SCIS promotes choice, diversity and -

Volume 20, No 10 2010

Jude, er, there's something you ought to know... I'm afraid that's all that's left of him... Lady Gaga and George Bush in shock summit meeting.. Just ask yourself one question: "Do I feel lucky?" Now, Andrew. Where’s your prep Potts calls Kettles Black. Contents 2 School captains 29 Speech and Drama 68 Golf 91 Prizewinners 2010 3 Headmaster's report 30 Tudor Rose 69 Cycling 92 History: HR Table tennis 4-5 Salvete 32 The Happiest Days of 96 Reels nights 6-7 Speech Day Your Life 70 Ski season 97 Hypnotist night Netball House Reports 34 The Little Shop of Horrors 98 Staff valete 71 Clay pigeon 8 Riley 38 Art 100 Obituaries 10 Freeland 72 Girls' tennis 43 Design & Technology 102 Charities 12 Nicol 73 Boys' tennis 14 Ruthven 48 Cricket 103 VI Form common room 74 Girls' hockey tour 16 Simpson 52 Rugby 104 The Ball 18 Thornbank 55 Football 76 CCF 20 Woodlands The Strathallian 2009-2010 58 Boys' hockey 78 Debating 22 Glenbrae Volume XX No. 10 60 Girls' Hockey 79 Chess 24 Chaplain’s report Editor: E G Kennedy 62 Swim team 80 Kenya 25 Headmaster’s Music Design: Douglas Colquhoun 82 Pipe band 63 Canoe club www.douglascolquhoun.co.uk 26 Headmaster’s Summer Music 84 Duke of Edinburgh's Award House Music 64 Cross-country and athletics Photography: Alaisdair Smith for Art and 86 Strathallian Club 27 Music department 65 Basketball Design Technology: Irene McFarlane: Karate 87 Strathallian news John Brittas and thanks to all staff who 28 Riley Music contributed.