Wernicke's Encephalopathy: Role of Thiamine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of the Biochemistry, Metabolism and Clinical Benefits of Thiamin(E) and Its Derivatives

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Advance Access Publication 1 February 2006 eCAM 2006;3(1)49–59provided by PubMed Central doi:10.1093/ecam/nek009 Review A Review of the Biochemistry, Metabolism and Clinical Benefits of Thiamin(e) and Its Derivatives Derrick Lonsdale Preventive Medicine Group, Derrick Lonsdale, 24700 Center Ridge Road, Westlake, OH 44145, USA Thiamin(e), also known as vitamin B1, is now known to play a fundamental role in energy metabolism. Its discovery followed from the original early research on the ‘anti-beriberi factor’ found in rice polish- ings. After its synthesis in 1936, it led to many years of research to find its action in treating beriberi, a lethal scourge known for thousands of years, particularly in cultures dependent on rice as a staple. This paper refers to the previously described symptomatology of beriberi, emphasizing that it differs from that in pure, experimentally induced thiamine deficiency in human subjects. Emphasis is placed on some of the more unusual manifestations of thiamine deficiency and its potential role in modern nutri- tion. Its biochemistry and pathophysiology are discussed and some of the less common conditions asso- ciated with thiamine deficiency are reviewed. An understanding of the role of thiamine in modern nutrition is crucial in the rapidly advancing knowledge applicable to Complementary Alternative Medi- cine. References are given that provide insight into the use of this vitamin in clinical conditions that are not usually associated with nutritional deficiency. The role of allithiamine and its synthetic derivatives is discussed. -

Nutrition 102 – Class 3

Nutrition 102 – Class 3 Angel Woolever, RD, CD 1 Nutrition 102 “Introduction to Human Nutrition” second edition Edited by Michael J. Gibney, Susan A. Lanham-New, Aedin Cassidy, and Hester H. Vorster May be purchased online but is not required for the class. 2 Technical Difficulties Contact: Erin Deichman 574.753.1706 [email protected] 3 Questions You may raise your hand and type your question. All questions will be answered at the end of the webinar to save time. 4 Review from Last Week Vitamins E, K, and C What it is Source Function Requirement Absorption Deficiency Toxicity Non-essential compounds Bioflavonoids: Carnitine, Choline, Inositol, Taurine, and Ubiquinone Phytoceuticals 5 Priorities for Today’s Session B Vitamins What they are Source Function Requirement Absorption Deficiency Toxicity 6 7 What Is Vitamin B1 First B Vitamin to be discovered 8 Vitamin B1 Sources Pork – rich source Potatoes Whole-grain cereals Meat Fish 9 Functions of Vitamin B1 Converts carbohydrates into glucose for energy metabolism Strengthens immune system Improves body’s ability to withstand stressful conditions 10 Thiamine Requirements Groups: RDA (mg/day): Infants 0.4 Children 0.7-1.2 Males 1.5 Females 1 Pregnancy 2 Lactation 2 11 Thiamine Absorption Absorbed in the duodenum and proximal jejunum Alcoholics are especially susceptible to thiamine deficiency Excreted in urine, diuresis, and sweat Little storage of thiamine in the body 12 Barriers to Thiamine Absorption Lost into cooking water Unstable to light Exposure to sunlight Destroyed -

Guidelines on Food Fortification with Micronutrients

GUIDELINES ON FOOD FORTIFICATION FORTIFICATION FOOD ON GUIDELINES Interest in micronutrient malnutrition has increased greatly over the last few MICRONUTRIENTS WITH years. One of the main reasons is the realization that micronutrient malnutrition contributes substantially to the global burden of disease. Furthermore, although micronutrient malnutrition is more frequent and severe in the developing world and among disadvantaged populations, it also represents a public health problem in some industrialized countries. Measures to correct micronutrient deficiencies aim at ensuring consumption of a balanced diet that is adequate in every nutrient. Unfortunately, this is far from being achieved everywhere since it requires universal access to adequate food and appropriate dietary habits. Food fortification has the dual advantage of being able to deliver nutrients to large segments of the population without requiring radical changes in food consumption patterns. Drawing on several recent high quality publications and programme experience on the subject, information on food fortification has been critically analysed and then translated into scientifically sound guidelines for application in the field. The main purpose of these guidelines is to assist countries in the design and implementation of appropriate food fortification programmes. They are intended to be a resource for governments and agencies that are currently implementing or considering food fortification, and a source of information for scientists, technologists and the food industry. The guidelines are written from a nutrition and public health perspective, to provide practical guidance on how food fortification should be implemented, monitored and evaluated. They are primarily intended for nutrition-related public health programme managers, but should also be useful to all those working to control micronutrient malnutrition, including the food industry. -

Vitamin and Mineral Requirements in Human Nutrition

P000i-00xx 3/12/05 8:54 PM Page i Vitamin and mineral requirements in human nutrition Second edition VITPR 3/12/05 16:50 Page ii WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Human Vitamin and Mineral Requirements (1998 : Bangkok, Thailand). Vitamin and mineral requirements in human nutrition : report of a joint FAO/WHO expert consultation, Bangkok, Thailand, 21–30 September 1998. 1.Vitamins — standards 2.Micronutrients — standards 3.Trace elements — standards 4.Deficiency diseases — diet therapy 5.Nutritional requirements I.Title. ISBN 92 4 154612 3 (LC/NLM Classification: QU 145) © World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2004 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from Market- ing and Dissemination, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 2476; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permis- sion to reproduce or translate WHO publications — whether for sale or for noncommercial distri- bution — should be addressed to Publications, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]), or to Chief, Publishing and Multimedia Service, Information Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 00100 Rome, Italy. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

341 Nutrient Deficiency Or Disease Definition/Cut-Off Value

10/2019 341 Nutrient Deficiency or Disease Definition/Cut-off Value Any currently treated or untreated nutrient deficiency or disease. These include, but are not limited to, Protein Energy Malnutrition, Scurvy, Rickets, Beriberi, Hypocalcemia, Osteomalacia, Vitamin K Deficiency, Pellagra, Xerophthalmia, and Iron Deficiency. Presence of condition diagnosed, documented, or reported by a physician or someone working under a physician’s orders, or as self-reported by applicant/participant/caregiver. See Clarification for more information about self-reporting a diagnosis. Participant Category and Priority Level Category Priority Pregnant Women 1 Breastfeeding Women 1 Non-Breastfeeding Women 6 Infants 1 Children 3 Justification Nutrient deficiencies or diseases can be the result of poor nutritional intake, chronic health conditions, acute health conditions, medications, altered nutrient metabolism, or a combination of these factors, and can impact the levels of both macronutrients and micronutrients in the body. They can lead to alterations in energy metabolism, immune function, cognitive function, bone formation, and/or muscle function, as well as growth and development if the deficiency is present during fetal development and early childhood. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that less than 10% of the United States population has nutrient deficiencies; however, nutrient deficiencies vary by age, gender, and/or race and ethnicity (1). For certain segments of the population, nutrient deficiencies may be as high as one third of the population (1). Intake patterns of individuals can lead to nutrient inadequacy or nutrient deficiencies among the general population. Intakes of nutrients that are routinely below the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI) can lead to a decrease in how much of the nutrient is stored in the body and how much is available for biological functions. -

Validation of Hplc Method for Determination of Thiamine Hydrochloride, Riboflavin, Nicotinamide, and Pyridoxine Hydrochl0ride in Syrup Preparation

Canadian Journal on Scientific and Industrial Research Vol. 2 No. 7, August 20ll VALIDATION OF HPLC METHOD FOR DETERMINATION OF THIAMINE HYDROCHLORIDE, RIBOFLAVIN, NICOTINAMIDE, AND PYRIDOXINE HYDROCHL0RIDE IN SYRUP PREPARATION NOVI YANTIH*, DIAH WIDOWATI, WARTINI, TIWI ARYANI Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Pancasila Email: novi_yantih @ yahoo.com Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Pancasila, Srengseng Sawah, Jagakarsa, 12640 South Jakarta, Indonesia ABSTRACT Multivitamin syrup containing various substances of varying characteristics may have a problem in quantitative analysis. This research has developed and validated of HPLC method for determination of four vitamin components, that is thiamine hydrochloride, riboflavin, nicotinamide, and pyridoxine hydrochloride in syrup multivitamin-mineral. The chromatographic separation was achieved by using a C18 column with dimension of 3.9x300mm and particle size of l0µm. A mixture of methanol - l% acetic acid by using 7mM 1-hexane sulphonic acid sodium salt (20:80) as mobile phase with flow rate of 1 mL/min. The effluent was monitored at 280 nm. Effective separation and quantification was achieved in less than 20 min. That method was simple, accurate, precise, and could be successfully applied for the analysis of thiamine hydrochloride, riboflavin, nicotinamide, and pyridoxine hydrochloride syrup multivitamin- mineral. Keywords: Thiamine hydrochloride, riboflavin, nicotinamide, pyridoxine hydrochloride, syrup, HPLC. 269 270 INTRODUCTION Syrup multivitamin and mineral preparations containing various substances of varying characteristics may have many problems in quantitative analysis. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) due to its high capacity in separating a mixture of substances was applicable in determining each component in multivitamin preparations simultaneously. Several investigator have reported the used of HPLC methods for the determination of water-soluble vitamins, such as thiamine hydrochloride, riboflavin, nicotinarnide, and pyridoxine hydrochloride in pharmaceuticals preparations [l,2,3]. -

Alcohol Related Dementia and Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome

About Dementia - 18 ALCOHOL RELATED DEMENTIA AND WERNICKE-KORSAKOFF SYNDROME This Help Sheet discusses alcohol related dementia and Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, their causes, symptoms and treatment. What is alcohol related dementia? Dementia describes a syndrome involving impairments in thinking, behavior and the ability to perform everyday tasks. Excessive consumption of alcohol over many years can sometimes result in brain damage that produces symptoms of dementia. Alcohol related dementia may be diagnosed when alcohol abuse is determined to be the most likely cause of the dementia symptoms. The condition can affect memory, learning, reasoning and other mental functions, as well as personality, mood and social skills. Problems usually develop gradually. If the person continues to drink alcohol at high levels, the symptoms of dementia are likely to get progressively worse. If the person abstains from alcohol completely then deterioration can be halted, and there is often some recovery over time. Excessive alcohol consumption can damage the brain in many different ways, directly and indirectly. Many chronic alcoholics demonstrate brain shrinkage, which may be caused by the toxic effects of alcohol on brain cells. Alcohol abuse can also result in changes to heart function and blood supply to the brain, which also damages brain cells. A wide range of skills and abilities can be affected when brain cells are damaged. Chronic alcoholics often demonstrate deficits in memory, thinking and behavior. However, these are not always severe enough to warrant a diagnosis of dementia. Many doctors prefer the terms ‘alcohol related brain injury’ or ‘alcohol related brain impairment’, rather than alcohol related dementia, because alcohol abuse can cause impairments in many different brain functions. -

Magnesium Deficiency: a Possible Cause of Thiamine Refractoriness in Wernicke-Korsakoff Encephalopathy

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.37.8.959 on 1 August 1974. Downloaded from Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 1974, 37, 959-962 Magnesium deficiency: a possible cause of thiamine refractoriness in Wernicke-Korsakoff encephalopathy D. C. TRAVIESA From the Department ofNeurology, University ofMiami School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, U.S.A. SYNOPSIS The determination of blood transketolase before and serially after thiamine administra- tion, and the response of clinical symptomatology after thiamine are reported in two normo- magnesaemic patients and one hypomagnesaemic patient with acute Wernicke-Korsakoff encephalopathy. The response of the depressed blood transketolase and the clinical symptoms was retarded in the hypomagnesaemic patient. Correction of hypomagnesaemia was accompanied by the recovery of blood transketolase activity and total clearing of the ophthalmoplegia in this patient, guest. Protected by copyright. suggesting that hypomagnesaemia may be a cause of the occasional thiamine refractoriness of these patients. Previous studies have shown that the clinical vestibular nuclei (Prickett, 1934; Dreyfus and entity of Wernicke-Korsakoff encephalopathy is Victor, 1961; Dreyfus, 1965). related to an exclusive deficiency of thiamine (Phillips et al., 1952). Furthermore, improvement Blood transketolase activity is markedly re- in clinical symptoms, once the syndrome has de- duced in patients with Wernicke-Korsakoff veloped, occurs only with the repletion of thi- encephalopathy and serial assays in these patients amine. It is this obvious and seemingly pure usually reveal a rapid and essentially complete causal relationship of thiamine deficiency and recovery of the reduced blood transketolase Wernicke-Korsakoff encephalopathy that neces- activity after the parental administration of sitates the total understanding of thiamine thiamine (Brin, 1962; Dreyfus, 1962). -

Magnesium: the Forgotten Electrolyte—A Review on Hypomagnesemia

medical sciences Review Magnesium: The Forgotten Electrolyte—A Review on Hypomagnesemia Faheemuddin Ahmed 1,* and Abdul Mohammed 2 1 OSF Saint Anthony Medical Center, 5666 E State St, Rockford, IL 61108, USA 2 Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center, 833 W Wellington Ave, Chicago, IL 60657, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 February 2019; Accepted: 2 April 2019; Published: 4 April 2019 Abstract: Magnesium is the fourth most abundant cation in the body and the second most abundant intracellular cation. It plays an important role in different organ systems at the cellular and enzymatic levels. Despite its importance, it still has not received the needed attention either in the medical literature or in clinical practice in comparison to other electrolytes like sodium, potassium, and calcium. Hypomagnesemia can lead to many clinical manifestations with some being life-threatening. The reported incidence is less likely than expected in the general population. We present a comprehensive review of different aspects of magnesium physiology and hypomagnesemia which can help clinicians in understanding, identifying, and treating this disorder. Keywords: magnesium; proton pump inhibitors; diuretics; hypomagnesemia 1. Introduction Magnesium is one of the most abundant cation in the body as well as an abundant intracellular cation. It plays an important role in molecular, biochemical, physiological, and pharmacological functions in the body. The importance of magnesium is well known, but still it is the forgotten electrolyte. The reason for it not getting the needed attention is because of rare symptomatology until levels are really low and also because of a lack of proper understanding of magnesium physiology. -

Enriched Flour

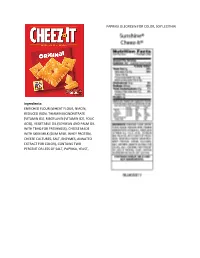

PAPRIKA OLEORESIN FOR COLOR, SOY LECITHIN. Ingredients: ENRICHED FLOUR (WHEAT FLOUR, NIACIN, REDUCED IRON, THIAMIN MONONITRATE [VITAMIN B1], RIBOFLAVIN [VITAMIN B2], FOLIC ACID), VEGETABLE OIL (SOYBEAN AND PALM OIL WITH TBHQ FOR FRESHNESS), CHEESE MADE WITH SKIM MILK (SKIM MILK, WHEY PROTEIN, CHEESE CULTURES, SALT, ENZYMES, ANNATTO EXTRACT FOR COLOR), CONTAINS TWO PERCENT OR LESS OF SALT, PAPRIKA, YEAST, INGREDIENTS CRUST: WHOLE GRAIN OATS, ENRICHED FLOUR (WHEAT FLOUR, NIACIN, REDUCED IRON, VITAMIN B1 [THIAMIN MONONITRATE], VITAMIN B2 [RIBOFLAVIN], FOLIC ACID), WHOLE WHEAT FLOUR, SOYBEAN AND/OR CANOLA OIL, SOLUBLE CORN FIBER, SUGAR, DEXTROSE, FRUCTOSE, CALCIUM CARBONATE, WHEY, WHEAT BRAN, SALT, CELLULOSE, POTASSIUM BICARBONATE, NATURAL AND ARTIFICIAL FLAVOR, CINNAMON, MONO- AND DIGLYCERIDES, SOY LECITHIN, WHEAT GLUTEN, NIACINAMIDE, VITAMIN A PALMITATE, CARRAGEENAN, ZINC OXIDE, REDUCED IRON, GUAR GUM, VITAMIN B6 (PYRIDOXINE HYDROCHLORIDE), VITAMIN B1 (THIAMIN HYDROCHLORIDE), VITAMIN B2 (RIBOFLAVIN), FILLING: INVERT SUGAR, CORN SYRUP, APPLE PUREE CONCENTRATE, GLYCERIN, SUGAR, MODIFIED CORN STARCH, SODIUM ALGINATE, MALIC ACID, METHYLCELLULOSE, DICALCIUM PHOSPHATE, CINNAMON, CITRIC ACID, CARAMEL COLOR. CONTAINS WHEAT, MILK AND SOY INGREDIENTS CRUST: WHOLE GRAIN OATS, ENRICHED FLOUR (WHEAT FLOUR, NIACIN, REDUCED IRON, VITAMIN B1 [THIAMIN MONONITRATE], VITAMIN B2 [RIBOFLAVIN], FOLIC ACID), WHOLE WHEAT FLOUR, SOYBEAN AND/OR CANOLA OIL, SOLUBLE CORN FIBER, SUGAR, DEXTROSE, FRUCTOSE, CALCIUM CARBONATE, WHEY, WHEAT BRAN, SALT, CELLULOSE, POTASSIUM -

Mechanism of Hypokalemia in Magnesium Deficiency

SCIENCE IN RENAL MEDICINE www.jasn.org Mechanism of Hypokalemia in Magnesium Deficiency Chou-Long Huang*† and Elizabeth Kuo* *Department of Medicine, †Charles and Jane Pak Center for Mineral Metabolism and Clinical Research, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas ABSTRACT deficiency is likely associated with en- ϩ Magnesium deficiency is frequently associated with hypokalemia. Concomitant hanced renal K excretion. To support magnesium deficiency aggravates hypokalemia and renders it refractory to treat- this idea, Baehler et al.5 showed that ad- ment by potassium. Herein is reviewed literature suggesting that magnesium ministration of magnesium decreases ϩ deficiency exacerbates potassium wasting by increasing distal potassium secre- urinary K excretion and increases se- ϩ tion. A decrease in intracellular magnesium, caused by magnesium deficiency, rum K levels in a patient with Bartter releases the magnesium-mediated inhibition of ROMK channels and increases disease with combined hypomagnesemia potassium secretion. Magnesium deficiency alone, however, does not necessarily and hypokalemia. Similarly, magnesium ϩ cause hypokalemia. An increase in distal sodium delivery or elevated aldosterone replacement alone (without K ) in- ϩ levels may be required for exacerbating potassium wasting in magnesium creases serum K levels in individuals deficiency. who have hypokalemia and hypomag- nesemia and receive thiazide treatment.6 J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2649–2652, 2007. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007070792 Magnesium administration decreased urinary Kϩ excretion in these individuals (Dr. Charles Pak, personal communica- Hypokalemia is among the most fre- cin B, cisplatin, etc. Concomitant magne- tion, UT Southwestern Medical Center quently encountered fluid and electro- sium deficiency has long been appreci- at Dallas, July 13, 2007). -

Circulatory and Urinary B-Vitamin Responses to Multivitamin Supplement Ingestion Differ Between Older and Younger Adults

nutrients Article Circulatory and Urinary B-Vitamin Responses to Multivitamin Supplement Ingestion Differ between Older and Younger Adults Pankaja Sharma 1,2 , Soo Min Han 1 , Nicola Gillies 1,2, Eric B. Thorstensen 1, Michael Goy 1, Matthew P. G. Barnett 2,3 , Nicole C. Roy 2,3,4,5 , David Cameron-Smith 1,2,6 and Amber M. Milan 1,3,4,* 1 The Liggins Institute, University of Auckland, Auckland 1023, New Zealand; [email protected] (P.S.); [email protected] (S.M.H.); [email protected] (N.G.); [email protected] (E.B.T.); [email protected] (M.G.); [email protected] (D.C.-S.) 2 Riddet Institute, Palmerston North 4474, New Zealand; [email protected] (M.P.G.B.); [email protected] (N.C.R.) 3 Food & Bio-based Products Group, AgResearch, Palmerston North 4442, New Zealand 4 High-Value Nutrition National Science Challenge, Auckland 1023, New Zealand 5 Department of Human Nutrition, University of Otago, Dunedin 9016, New Zealand 6 Singapore Institute for Clinical Sciences, Agency for Science, Technology, and Research, Singapore 117609, Singapore * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +64-(0)9-923-4785 Received: 23 October 2020; Accepted: 13 November 2020; Published: 17 November 2020 Abstract: Multivitamin and mineral (MVM) supplements are frequently used amongst older populations to improve adequacy of micronutrients, including B-vitamins, but evidence for improved health outcomes are limited and deficiencies remain prevalent. Although this may indicate poor efficacy of supplements, this could also suggest the possibility for altered B-vitamin bioavailability and metabolism in older people.