Enlightenment Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 1 – Oxygen: the Gas That Changed Everything

MYSTERY OF MATTER: SEARCH FOR THE ELEMENTS 1. Oxygen: The Gas that Changed Everything CHAPTER 1: What is the World Made Of? Alignment with the NRC’s National Science Education Standards B: Physical Science Structure and Properties of Matter: An element is composed of a single type of atom. G: History and Nature of Science Nature of Scientific Knowledge Because all scientific ideas depend on experimental and observational confirmation, all scientific knowledge is, in principle, subject to change as new evidence becomes available. … In situations where information is still fragmentary, it is normal for scientific ideas to be incomplete, but this is also where the opportunity for making advances may be greatest. Alignment with the Next Generation Science Standards Science and Engineering Practices 1. Asking Questions and Defining Problems Ask questions that arise from examining models or a theory, to clarify and/or seek additional information and relationships. Re-enactment: In a dank alchemist's laboratory, a white-bearded man works amidst a clutter of Notes from the Field: vessels, bellows and furnaces. I used this section of the program to introduce my students to the concept of atoms. It’s a NARR: One night in 1669, a German alchemist named Hennig Brandt was searching, as he did more concrete way to get into the atomic every night, for a way to make gold. theory. Brandt lifts a flask of yellow liquid and inspects it. Notes from the Field: Humor is a great way to engage my students. NARR: For some time, Brandt had focused his research on urine. He was certain the Even though they might find a scientist "golden stream" held the key. -

Soda Can Calorimeter

Publication No. 10861 Soda Can Calorimeter Energy Content of Food Introduction Have you ever noticed the nutrition label located on the packaging of the food you buy? One of the first things listed on the label are the calories per serving. How is the calorie content of food determined? This activity will introduce the concept of calo- rimetry and investigate the caloric content of snack foods. Concepts • Calorimetry • Conservation of energy • First law of thermodynamics Background The law of conservation of energy states that energy cannot be created or destroyed, only converted from one form to another. This fundamental law was used by scientists to derive new laws in the field of thermodynamics—the study of heat energy, temper- ature, and heat transfer. The First Law of Thermodynamics states that the heat energy lost by one body is gained by another body. Heat is the energy that is transferred between objects when there is a difference in temperature. Objects contain heat as a result of the small, rapid motion (vibrations, rotational motion, electron spin, etc.) that all atoms experience. The temperature of an object is an indirect measurement of its heat. Particles in a hot object exhibit more rapid motion than particles in a colder object. When a hot and cold object are placed in contact with one another, the faster moving particles in the hot object will begin to bump into the slower moving particles in the colder object making them move faster (vice versa, the faster particles will then move slower). Eventually, the two objects will reach the same equilibrium temperature—the initially cold object will now be warmer, and the initially hot object will now be cooler. -

James Hutton November 1740, at the Age of Fourteen, He Entered the University of Edinburgh

James Hutton November 1740, at the age of fourteen, he entered the University of Edinburgh. This was not as remarkable as it now sounds, for at this time the Scottish universities competed with the schools to educate the brightest pupils. At the University of Edinburgh Hutton was taught mathematics by Maclaurin and logic and metaphysics by John Stevenson. He graduated in the spring of 1743, still only seventeen years old. After graduating, Hutton took a job as an apprentice to a solicitor, but his mind was not on the work as Playfair recounts: ... the young man's propensity to study continued, and he was often found amusing himself and his fellow apprentices with chemical experiments when he should have been copying papers, or studying the forms of legal proceedings. Hutton, deciding to take the training, which involved the most chemistry, returned to the Born: 3 June 1726 in Edinburgh, Scotland University of Edinburgh in November 1744 to Died: 26 March 1797 in Edinburgh, Scotland undertake medical studies. However before he could begin his second year of studies the 1745 James Hutton's mother was Sarah Balfour and rebellion had broken out and his former his father was William Hutton. James was born lecturer Maclaurin was organising the defence into a wealthy family for his father William was of the city against the Jacobite armies. It was a a merchant who held the office of Edinburgh year before he could resume his studies, which city treasurer. he did in 1746. William owned a 140 acre farm at Slighhouses In 1747 Hutton fathered an illegitimate child. -

34 Bull. Hist. Chem. 10

3 ll t Ch 10 (1991 mained an important consideration. The flow-type calomel nt Appld t r Cntrl" Ind. Eng. Chem., 19 14, electrode could be replaced by one designed to give an almost 11-11 negligible flow of potassium chloride solution. One of the 1 C Arthr nd E A Klr "A Mtr fr rdn th most successful designs, described in 1947, made use of a Allnt f lr-d Wtr" Power, 19 55, 7-77 controlled-crack junction tube (19). Pyrex glass was used for 15 C C Cn "Cntn Mrnt f p th Qnh- the body of the tube, A hole 5 to 10 mm in diameter was blown drn Eltrd" Ind. Eng. Chem., Anal. Ed., 1931 3, -7 in the bottom and the hole was closed by sealing in a plug of 16.J. T. St W C rd nd M Gr "h Antn- glass having a high coefficient of expansion. After proper Antn Oxd Eltrd" Chem, Rev., 195 58, 11- annealing, a permanent crack of controlled dimensions was 17 G A rl "Antn Eltrd fr Indtrl drn- obtained. A typical leak rate was 0.006 mL/hr. In Mrnt" Ind. Eng. Chem., Anal. Ed., 1939 11, 31-31 Because of improvements in instrumentation, the high 1 G A rl "Chrtrt f th Antn Eltrd" resistance of the glass electrode ceased to be a handicap, and Ind. Eng. Chem., Anal. Ed., 1939 11, 319-3 it became the pH electrode of choice. Once this had occurred, 19 G A rl An Indtrl Slt-rd ntn b" highly-specialized glasses that provided a stable, much im- Trans. -

Physics, Chapter 15: Heat and Work

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 15: Heat and Work Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 15: Heat and Work" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 167. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/167 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 15 Heat and Work 15-1 The Nature of Heat Until about 1750 the concepts of heat and temperature were not clearly distinguished. The two concepts were thought to be equivalent in the sense that bodies at equal temperatures were thought to "contain" equal amounts of heat. Joseph Black (1728-1799) was the first to make a clear distinction between heat and temperature. Black believed that heat was a form of matter, which subsequently came to be called caloric, and that the change in temperature of a body when caloric was added to it was associated with a property of the body which he called the capacity. Later investigators endowed caloric with additional properties. The caloric fluid was thought to embody a kind of universal repulsive force. When added to a body, the repulsive force of the caloric fluid caused the body to expand. -

THE MAN of SCIENCE Steven Shapin

THE IMAGE OF THE MAN OF SCIENCE Steven Shapin The relations between the images of the man of science and the social and cultural realities of scientific roles are both consequential and contingent. Finding out “who the guys were” (to use Sir Lewis Namier’s phrase) does in- deed help to illuminate what kinds of guys they were thought to be, and, for that reason alone, any survey of images is bound to deal – to some extent at least – with what are usually called the realities of social roles.1 At the same time, it must be noted that such social roles are always very substantially con- stituted, sustained, and modified by what members of the culture think is, or should be, characteristic of those who occupy the roles, by precisely whom this is thought, and by what is done on the basis of such thoughts. In socio- logical terms of art, the very notion of a social role implicates a set of norms and typifications – ideals, prescriptions, expectations, and conventions thought properly, or actually, to belong to someone performing an activity of a certain kind. That is to say, images are part of social realities, and the two notions can be distinguished only as a matter of convention. Such conventional distinctions may be useful in certain circumstances. So- cial action – historical and contemporary – very often trades in juxtapositions between image and reality. One might hear it said, for example, that modern American lawyers do not really behave like the high-minded professionals 1 For introductions to pertinent prosopography, see, e.g., Robert M. -

Paganelli HOPE Adam Smith and the Scottish Enlightenment With

Recent Engagements with Adam Smith and the Scottish Enlightenment by Maria Pia Paganelli CHOPE Working Paper No. 2015-06 June 2015 Recent Engagements with Adam Smith and the Scottish Enlightenment Maria Pia Paganelli Trinity University [email protected] Forthcoming, History of Political Economy, 2015 Abstract Recent literature on Adam Smith and other 18th Scottish thinkers shows an engaged conversation between the Scots and today’s scholars in the sciences that deal with humans—social sciences, humanities, as well as neuroscience and evolutionary psychology. We share with the 18th century Scots preoccupations about understanding human beings, human nature, sociability, moral development, our ability to understand nature and its possible creator, and about the possibilities to use our knowledge to improve our surrounding and standards of living. As our disciplines evolve, the studies of Smith and Scottish Enlightenment evolve with them. Smith and the Scots remain our interlocutors. Keywords: adam smith, david hume, scottish enlightenment, recent literature JLE: A1; A12; A13; A14; B1; B3; B30; B31; B4; B40; B41; C9; C90 1 Forthcoming, History of Political Economy, 2015 Recent Engagements with Adam Smith and the Scottish Enlightenment 1 Maria Pia Paganelli David Levy once told me: “Adam Smith is still our colleague. He's not in the office but he's down the hall.” Recent literature on Adam Smith and the Scottish Enlightenment shows Levy right. At the time of writing, searching Econlit peer review journal articles for “Adam Smith” in the abstract gives 480 results since year 2000. Opening the search to Proquest gives 1870 results since 2000 (see Appendix 2 to get a rough sense of the size of recent literature). -

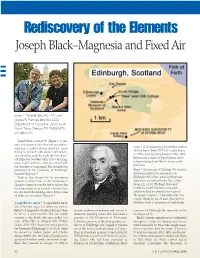

Joseph Black-Magnesia and Fixed Air

Rediscovery of the Elements Joseph Black-Magnesia and Fixed Air Firth of Edinburgh, Scotland Forth City Center Edinburgh (South Bridge Castle +0"-"New" (and Old) College National 0 Museum of Mseotfd Black's later Scotland home James L. Marshal, Beta Eta 1971, and Virginia R. Marshall, Beta Eta 2003, 1 l1kmII Department of Chemistry, University of North Texas, Denton, TX 76203-5070, MODERN UNIVERSITY [email protected] Joseph Black of EDINBURGH Building 9 Joseph Black (1728-1799) (Figure 1) is per- haps best known for the discovery and charac- terization of carbon dioxide (fixed air), made Figure 1. (Left) Engraving of Joseph Black, made in during his research with alkalies and carbon- 1800 by James Heath (1757-1834), taken from a ates. Simultaneously, he made the first chemi- ca 1790 portraitby Henry Raeburn (1756-1823). cal distinction between calcia (CaO) and mag- 4 Raeburn was a student of David Martin, whose nesia (MgO) and thus could be credited with portrait of young Joseph Black is shown on the the discovery of magnesium. This research was front cover performed at the University of Edinburgh, Figure 2. Modern map of Edinburgh. The chemical Scotland (Figure 2)." discoveries of Black were performed at the Black is also known for his pioneering Edinburgh "Old College,"whose buildings were research in latent heat at the University of taken down and replaced by the "New College" Glasgow, where he was the first to notice that during 1827-1831. The Royal Museum of the temperature of an ice-water mixture does Scotland is located 200 meters west, where not rise above the freezing point of water until exhibits on Black are presented (see Figure 8). -

The Cullen Consultation Letters

HISTORY THE CULLEN CONSULTATION LETTERS J. Dallas, Rare Books Librarian, Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh Within the pages of Andrew Carnegie’s biography of the Scottish engineer James Watt, you can find the statement: ‘It would be difficult to name an invention more universally used.’ With the name James Watt, one automatically thinks of the steam engine. Reading on, however, it is surprising to find that Carnegie is referring to something quite different. It would be difficult to name an invention more universally used in all offices where man labors in any field of activity. In the list of modest inventions of greatest usefulness, the modern copying-press must take high rank, and this we owe entirely to Watt.1 Watt refers to this invention in a letter he wrote to Joseph Black, Professor of Chemistry at Edinburgh. The two men had become close friends when Black was Professor of Chemistry at Glasgow and Watt was instrument maker to the University. In 1766 Black moved to Edinburgh to succeed William Cullen who had resigned the Chair of Chemistry to become Professor of the Institutes of Medicine. In 1774 Watt moved on to Birmingham. Watt and Black’s friendship and professional interests were thereafter sustained mainly by correspondence. In July of 1779 Watt wrote to his old friend that he had: FIGURE 1 lately discovered a method of copying writing William Cullen, age 58, after William Cochrane. instantaneously, provided it has been written within Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh twenty-four hours. I send you a specimen and will impart the secret if it will be of any use to you. -

The Scientific Publications of Alexander Marcet

Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 43, Number 2 (2018) 61 THE SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS OF ALEXANDER MARCET G. J. Leigh, University of Sussex, [email protected], and Carmen J. Giunta, Le Moyne College, [email protected] Supplemental material Abstract 1808 when he was elected to the Royal Society. French was his native language and this enabled him to maintain This paper lists all the publications which can be contacts with French and Swiss researchers, and to act as attributed to Alexander Marcet, a physician, chemist foreign secretary to, for example, the Geological Society and geologist active during the first two decades of the of London. He died in 1822. His scientific activities show nineteenth century. The contents of each publication are how, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, chem- described and assessed. Marcet was a practicing physi- istry in Britain was professionally and institutionally cian at a time and place when many chemists had medical intertwined with medicine, even while other chemists connections. His chemical work is primarily analytical were breaking free from it. and it also demonstrates how chemistry might eventu- Detailed information on Alexander and Jane Marcet ally shed light on how the human body deals with the is still easily available, and Jane’s life, in particular, has materials it has ingested. been described in considerable detail (1). However, Alex- ander’s professional career has been relatively neglected. Introduction This paper is an attempt to illustrate that he was no mere helper to his exceptional wife, but a significant figure in Alexander Marcet (1770-1822) and his wife Jane his own right. -

Joseph Black–Magnesia and Fixed Air III

Rediscovery of the Elements Joseph Black–Magnesia and Fixed Air III James L. Marshall, Beta Eta 1971, and Virginia R. Marshall, Beta Eta 2003, Department of Chemistry, University of North Texas, Denton, TX 76203-5070, [email protected] Joseph Black (1728–1799) (Figure 1) is per- haps best known for the discovery and charac- terization of carbon dioxide (fixed air), made Figure 1. (Left) Engraving of Joseph Black, made in during his research with alkalies and carbon- 1800 by James Heath (1757–1834), taken from a ates. Simultaneously, he made the first chemi- ca 1790 portrait by Henry Raeburn (1756–1823). cal distinction between calcia (CaO) and mag- Raeburn was a student of David Martin, whose nesia (MgO) and thus could be credited with portrait of young Joseph Black is shown on the the discovery of magnesium. This research was front cover. performed at the University of Edinburgh, Figure 2. Modern map of Edinburgh. The chemical Scotland (Figure 2).1b discoveries of Black were performed at the Black is also known for his pioneering Edinburgh “Old College,” whose buildings were research in latent heat at the University of taken down and replaced by the “New College” Glasgow, where he was the first to notice that during 1827–1831. The Royal Museum of the temperature of an ice-water mixture does Scotland is located 200 meters west, where not rise above the freezing point of water until exhibits on Black are presented (see Figure 8). all of the ice has melted (Figure 3).1d The modern campus is 2.7 km south of the “New College.” During his last 18 years, Black lived on Joseph Black’s career.1b,d,2 Joseph Black’s family Nicholson Street, a continuation of South Bridge. -

James Hutton & Joseph Black

James Hutton & Joseph Black John Playfair (1748-1819) was born in the parish of Liff and Benvie, on the outskirts of Dundee, where his father was minister. He graduated at the University of St Andrews in 1765. After completing his theological studies, Playfair came to Edinburgh in 1769, where he resided until 1772. According to his nephew and biographer, James Playfair, he then became acquainted with Joseph Black, the chemist, James Hutton and Adam Smith, the economist. Playfair himself noted (see p. 74) that his acquaint ance with Hutton dated from about 1781. From 1773 until 1782 Playfair was the incumbent of his father's parish near Dundee. He was appointed to the Chair of Mathematics in the University of Edinburgh in 1781, and translated to that of Natural Philosophy in 1805, a post he held until his death in 1819. Playfair earned a considerable reputation in at least three branches of learning — mathematics, history of sciences and especially geology. His book Illustrations of the Huttonian Theory, published in 1802, five years after Hutton's death is a marvellously clear and logical exposition and extension of Hutton's Theory. And having done justice to Hutton's sci ence he set about doing equal justice to Hutton, in an address to the Society on January 10, 1803. It seems highly appropriate to reprint this delightful article in 1997, the bicentenary of the death of James Hutton. The biography is an affectionate account of Hutton and his catholic interests and a wonderful piece of English prose. It has many marvellous episodes including the reaction of Hutton to finding granite veins at Glen Tilt (pp.