The Cutaneous Sensory System Neuroscience and Biobehavioral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tbwhat You Need to Know About the Tuberculosis Skin Test

What You Need to Know About TB the Tuberculosis Skin Test “I was told I needed a TB skin test, so I went to the health clinic. It was quick and didn’t hurt. In two days, I went back to the clinic so the nurse could see the results. It’s important to go back in 2 or 3 days to get your results or you will have to get the test again.” A TB skin test will tell you if you have ever had TB germs in your body. • A harmless fluid is placed under your skin on the inside of your arm. A very small needle is used, so you will only feel a light pinch. • Make sure you don’t put a bandage or lotion on the test spot. Also—don’t scratch the spot. If the area itches, put an ice cube or cold cloth on it. It is okay for the test spot to get wet, but do not wipe or scrub the area. • Return to the clinic or doctor’s office in 2 to 3 days so your healthcare provider can look at the test spot on your arm. He or she will look at the test spot and measure any bump that appears there. Your healthcare provider will let you know if your test is negative or positive. Write the time and date you will need to return here: 2 Remember—only a healthcare provider can read your TB skin test results the right way. When your skin test is positive: • You have TB germs in your body. -

Nail Anatomy and Physiology for the Clinician 1

Nail Anatomy and Physiology for the Clinician 1 The nails have several important uses, which are as they are produced and remain stored during easily appreciable when the nails are absent or growth. they lose their function. The most evident use of It is therefore important to know how the fi ngernails is to be an ornament of the hand, but healthy nail appears and how it is formed, in we must not underestimate other important func- order to detect signs of pathology and understand tions, such as the protective value of the nail plate their pathogenesis. against trauma to the underlying distal phalanx, its counterpressure effect to the pulp important for walking and for tactile sensation, the scratch- 1.1 Nail Anatomy ing function, and the importance of fi ngernails and Physiology for manipulation of small objects. The nails can also provide information about What we call “nail” is the nail plate, the fi nal part the person’s work, habits, and health status, as of the activity of 4 epithelia that proliferate and several well-known nail features are a clue to sys- differentiate in a specifi c manner, in order to form temic diseases. Abnormal nails due to biting or and protect a healthy nail plate [1 ]. The “nail onychotillomania give clues to the person’s emo- unit” (Fig. 1.1 ) is composed by: tional/psychiatric status. Nail samples are uti- • Nail matrix: responsible for nail plate production lized for forensic and toxicology analysis, as • Nail folds: responsible for protection of the several substances are deposited in the nail plate nail matrix Proximal nail fold Nail plate Fig. -

Touch and Temperature Senses

1 In press in Proceedings of the Association for Biology Laboratory Education (ABLE), 2004 Touch and Temperature Senses by Charlie Drewes Ecology, Evolution & Organismal Biology Iowa State University Ames, IA 50011 (515) 294-8061 [email protected] http://www.eeob.iastate.edu/faculty/DrewesC/htdocs/ Biographical: Charlie Drewes received a BA in biology from Augustana College (SD) and his MS and PhD in zoology from Michigan State University. Currently, he is a professor in Ecology, Evolution and Organismal Biology at Iowa State University. His research focus is on rapid escape reflexes and locomotion, especially in oligochaete worms. Charlie teaches courses in invertebrate biology, neurobiology and bioethics. During summers, he leads hands-on, residential workshops for high school biology teachers at Iowa Lakeside Lab. In 1998, he received the Distinguished Science Teaching Award from the Iowa Academy of Science and, in 2002, he received the Four-year College Biology Teaching Award from the National Association of Biology Teachers. Abstract: This investigation focuses on the sensory biology of human touch and temperature reception. Students investigate quantitative and qualitative aspects of touch-sensory functions in human skin. Values for two-point discrimination are compared to Weber’s original data. Also, novel materials and methods are introduced for investigating the functional organization of cold sensory reception in human skin, including: (a) estimation of sensory field size for single cold-sensory fibers, (b) demonstration of the discontinuous distribution of cold-sensory fibers in skin, and (c) estimation of the density of cold-sensitive fibers per unit area of skin. Tactile and thermoreceptor functions are related to underlying neuroanatomy of peripheral and central neural pathways. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

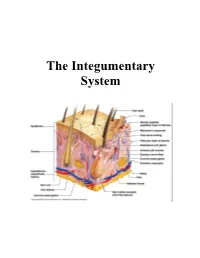

CHAPTER 4 the Integumentary System

CHAPTER 4 The Integumentary System LEARNING OBJECTIVES Upon completion of this chapter, you should be able to: • Name the two layers of the skin. • Name the accessory structures of the integumentary system. • Build and pronounce medical terms of the integumentary system. • Name the disorders and treatments relating to the integumentary system. • Name the major classifi cations of pharmacologic agents used to treat skin disorders. • Analyze and defi ne the new terms introduced in this chapter. • Interpret abbreviations associated with the integumentary system. 53 54 PART TWO • BODY SYSTEMS Introduction The largest organ of the body is the skin. The skin covers the entire body—more than 20 square feet on average—and weighs about 24 pounds. It is part of the integumentary system, which also includes the accessory structures: hair, nails, and sebaceous (oil) and sudoriferous (sweat) glands. Integumentum is Latin for “covering” or “shelter.” The physician who specializes in the diag- nosis and treatment of skin disorders is called a dermatologist (dermat/o being one of the com- bining forms for skin). Coupling the root dermat/o with the previously learned suffi x -logy gives us the term dermatology , which is the term for the specialty practice that deals with the skin. Word Elements The major word elements that relate to the integumentary system consist of various anatomical components, accessory structures, colors of the skin, and abnormal conditions. The Word Ele- ments table lists many of the roots, their meanings, and examples associated -

HAIR SKIN NAILS BEAUTIFYING SUPPLEMENT with KERATIN and BIOTIN 60 Capsules

PRODUCT INFO HAIR SKIN NAILS BEAUTIFYING SUPPLEMENT WITH KERATIN AND BIOTIN 60 Capsules With key ingredients Biotin and Keratin, Hair Skin Nails helps boost your body’s natural Collagen and Keratin production so you can easily achieve and maintain healthy structures for your hair, skin, and nails.† By adding just two capsules to your morning routine, you’ll see healthier hair, more radiant skin, and stronger nails that begin from within.† Features and Benefits: • Includes Vitamin A and Biotin for healthy hair growth, strong nails, and glowing skin† • Boosts your body’s natural Collagen and Keratin production† • Moisturizes while enhancing skin elasticity and flexibility† • Supports your body’s defenses against free-radical damage† • Protects and supports natural skin renewal with Zinc, Copper, and Manganese† SUGGESTED USE Take two Hair Skin Nails capsules daily with food to nourish your hair, skin, and nails from within. For optimal benefits, pair Hair Skin Nails with the complete It Works! BeautyWorks skincare line. CAUTION Consult your physician if you are pregnant, nursing, taking medication, or have a medical condition. WARNING Other Ingredients: Rice flour, vegetable capsule Keep out of reach of children. Do not use if tamper- (hypromellose, black/purple carrot concentrate), evident seal is broken or missing. Store at 59°-86° F magnesium stearate, and silica. (15°-30° C). Protect from heat, light, and moisture. 1 pis-hsn-us-en-007 †These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. PRODUCT INFO HAIR SKIN NAILS BEAUTIFYING SUPPLEMENT WITH KERATIN AND BIOTIN FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS When and how should I take Hair Skin Nails? What are the benefits of regularly taking To achieve your best results, take two Hair Skin Nails Hair Skin Nails? capsules every day with food. -

Getting Help for Skin Changes

Getting Help for Skin Changes Cancer and cancer treatment can cause skin changes like rashes, dry skin, color changes, and itching. Skin changes are often side effects and part of your Hand-foot syndrome (HFS) has been linked to many body's normal response to the treatment. If skin cancer treatment drugs. Pain, sensitivity, tingling, and changes develop very suddenly while you are receiving numbness are early symptoms of HFS. Then, redness a drug used to treat cancer, they could be a sign that and swelling start on the palms of the hands and the you are allergic to that drug. soles of the feet. This redness looks a lot like sunburn and may blister. In bad cases, the blisters can open up It is very important to tell your doctor or nurse about and become sores. The skin also can become dry, peel, any skin changes you notice. If not treated, they can get and crack. worse and some might lead to infection. Skin color changes can happen due to the side effects What common skin changes should I of some cancer treatments, tumor growth, or being in watch for? the sun. Some color changes may get better with time. Other color changes may last longer. Rash is a common side effect of some cancer treatments. The risk of getting a rash and how bad it is depends on the type of cancer and the type of treatment you get. What you can do to prevent or control Rashes can show up on the scalp, face, neck, chest, skin changes upper back, and sometimes on other parts of the body. -

Draft of Content Outline

American Board of Dermatology Content Outline The American Board of Dermatology (ABD) has produced this content outline to help dermatology residents understand the scope of information covered in the ABD certifying examination. This list is not exhaustive and content for examination questions will also come from new and evolving concepts. Hopefully, this will help guide preparation and alleviate some test preparation anxiety. I) Basic Science A) Gross Anatomy B) Tumor biology and pathogenesis C) Photobiology D) Biochemistry E) Cell biology 1) Apoptosis 2) Cell cycle F) Embryology G) Epidemiology H) Genetics 1) Basic principles of genetics 2) Genetic basis of cutaneous diseases I) Immunology 1) Autoantibodies (autoimmune connective tissue) diseases 2) Autoantibodies (vesiculobullous disorders) J) Microbiology K) Bacteriology 1) Fungi 2) Parasites 3) Protozoa 4) Viruses L) Molecular biology M) Wound healing N) Pharmacology O) Skin barrier, percutaneous drug delivery, and pharmacokinetics P) Physiology 1) Biology of the basement membrane zone 2) Structure and function of eccrine, apocrine, apoeccrine, and sebaceous glands 3) Biology of keratinocytes 4) Biology of melanocytes 5) Biology of the extracellular matrix 6) Vascular biology 7) Biology of hair and nails 8) Biology of mast cells and eosinophils 9) Inflammatory mediators Q) Research Design II) General/Medical Dermatology & Therapy A) General Principles 1) Normal growth and development 1 2) Public health 3) Statistics 4) Physical Examination and diagnosis B) Pruritus 1) Mediators of pruritus 2) Pruritus and dysesthesia 3) Psychocutaneous diseases C) Papulosquamous dermatoses 1) Psoriasis 2) Pityriasis rubra pilaris 3) Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses 4) Other papulosquamous disorders, e.g. pityriasis rosea, secondary syphilis D) Eczematous dermatoses 1) Atopic dermatitis 2) Allergic contact dermatitis 3) Stasis dermatitis 4) Other eczematous conditions, e.g. -

What Are Basal and Squamous Cell Skin Cancers?

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 About Basal and Squamous Cell Skin Cancer Overview If you have been diagnosed with basal or squamous cell skin cancer or are worried about it, you likely have a lot of questions. Learning some basics is a good place to start. ● What Are Basal and Squamous Cell Skin Cancers? Research and Statistics See the latest estimates for new cases of basal and squamous cell skin cancer and deaths in the US and what research is currently being done. ● Key Statistics for Basal and Squamous Cell Skin Cancers ● What’s New in Basal and Squamous Cell Skin Cancer Research? What Are Basal and Squamous Cell Skin Cancers? Basal and squamous cell skin cancers are the most common types of skin cancer. They start in the top layer of skin (the epidermis), and are often related to sun exposure. 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Cancer starts when cells in the body begin to grow out of control. Cells in nearly any part of the body can become cancer cells. To learn more about cancer and how it starts and spreads, see What Is Cancer?1 Where do skin cancers start? Most skin cancers start in the top layer of skin, called the epidermis. There are 3 main types of cells in this layer: ● Squamous cells: These are flat cells in the upper (outer) part of the epidermis, which are constantly shed as new ones form. When these cells grow out of control, they can develop into squamous cell skin cancer (also called squamous cell carcinoma). -

The Integumentary System

The Integumentary System THE INTEGUMENTARY SYSTEM Skin is the system of the body that makes an individual beautiful! Skin/fur coloration allows animals to be camouflaged. *The skin is the largest organ of the body. The skin and its derivatives (hair, nails, sweat and oil glands) make up the integumentary system. The total surface area of the skin is about 1.8 m² and its total weight is about 11 kg. The skin gives us our appearance and shape. Anatomy of the Skin • Skin is made up of two layers that cover a third fatty layer. The outer layer is called the epidermis; it is a tough protective layer. The second layer (located under the epidermis) is called the dermis; it contains nerve endings, sweat glands, oil glands, and hair follicles. Under these two skin layers is a fatty layer called the subcutaneous tissue, or hypodermis. 1 • The dermis is home to the oil glands. These are also called sebaceous glands, and they are always producing sebum. Sebum is your skin's own natural oil. It rises to the surface of your epidermis to keep your skin lubricated and protected. It also makes your skin waterproof. • Skin is alive! It's made of many thin sheets of flat, stacked cells. Older cells are constantly being pushed to the surface by new cells, which grow from below. When the old ones reach the top, they become wider and flatter as they get rubbed and worn by all your activity. And, sooner or later, they end up popping off like tiles blown from a roof in a strong wind. -

Fur, Feathers, and Scales

ZAP!ZAP! Zoo Activity Packet Fur, Feathers, and Scales A Teacher's Resource for Grade 1 www.kidszoo.org Fur, Feathers, and Scales/Grade 1 Fur, Feathers and Scales ZAP! Zoo Activity Packet Table of Contents Learning Objectives page 3 Background Information for the Teacher page 4 Pre-Visit Activities page 7 At-the-Zoo Activities page 12 Post-Visit Activities page 15 Resources page 24 Evaluation Form page 29 Fort Wayne Children's Zoo Activity Packet 2 www.kidszoo.org Fur, Feathers, and Scales/Grade 1 Fur, Feathers, and Scales Zoo Activity Packet Learning Objectives The work sheets and activities in this Zoo Activity Packet are suggested to help students learn that: 1. Animals have different body coverings depending on what class they belong to: Mammals - fur or hair Birds - feathers Reptiles - dry scales Amphibians - moist, smooth skin Fish - wet, slimy scales 2. Animal coverings come in a variety of colors and patterns. 3. Colors and patterns protect animals by: -helping them blend into their surroundings (example: a tiger in tall grass). -making them look like something else (example: a walking stick insect). -warning others to stay away (example: skunk). 4. Animals bodies are different shapes and sizes. They don’t all have the same characteristics (example: number of legs, position of eyes and ears on head, tails, toes, etc.). Fort Wayne Children's Zoo Activity Packet 3 www.kidszoo.org Fur, Feathers, and Scales/Grade 1 Background Information for the Teacher: Animal Body Coverings Types of Body Coverings So we can study them more easily, animals are grouped into classes according to their characteristics. -

Basic Biology of the Skin 3

© Jones and Bartlett Publishers, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION CHAPTER Basic Biology of the Skin 3 The skin is often underestimated for its impor- Layers of the skin: tance in health and disease. As a consequence, it’s frequently understudied by chiropractic students 1. Epidermis—the outer most layer of the skin (and perhaps, under-taught by chiropractic that is divided into the following fi ve layers school faculty). It is not our intention to present a from top to bottom. These layers can be mi- comprehensive review of anatomy and physiol- croscopically identifi ed: ogy of the skin, but rather a review of the basic Stratum corneum—also known as the biology of the skin as a prerequisite to the study horny cell layer, consisting mainly of kera- of pathophysiology of skin disease and the study tinocytes (fl at squamous cells) containing of diagnosis and treatment of skin disorders and a protein known as keratin. The thick layer diseases. The following material is presented in prevents water loss and prevents the entry an easy-to-read point format, which, though brief of bacteria. The thickness can vary region- in content, is suffi cient to provide a refresher ally. For example, the stratum corneum of course to mid-level or upper-level chiropractic the hands and feet are thick as they are students and chiropractors. more prone to injury. This layer is continu- Please refer to Figure 3-1, a cross-sectional ously shed but is replaced by new cells from drawing of the skin. This represents a typical the stratum basale (basal cell layer).