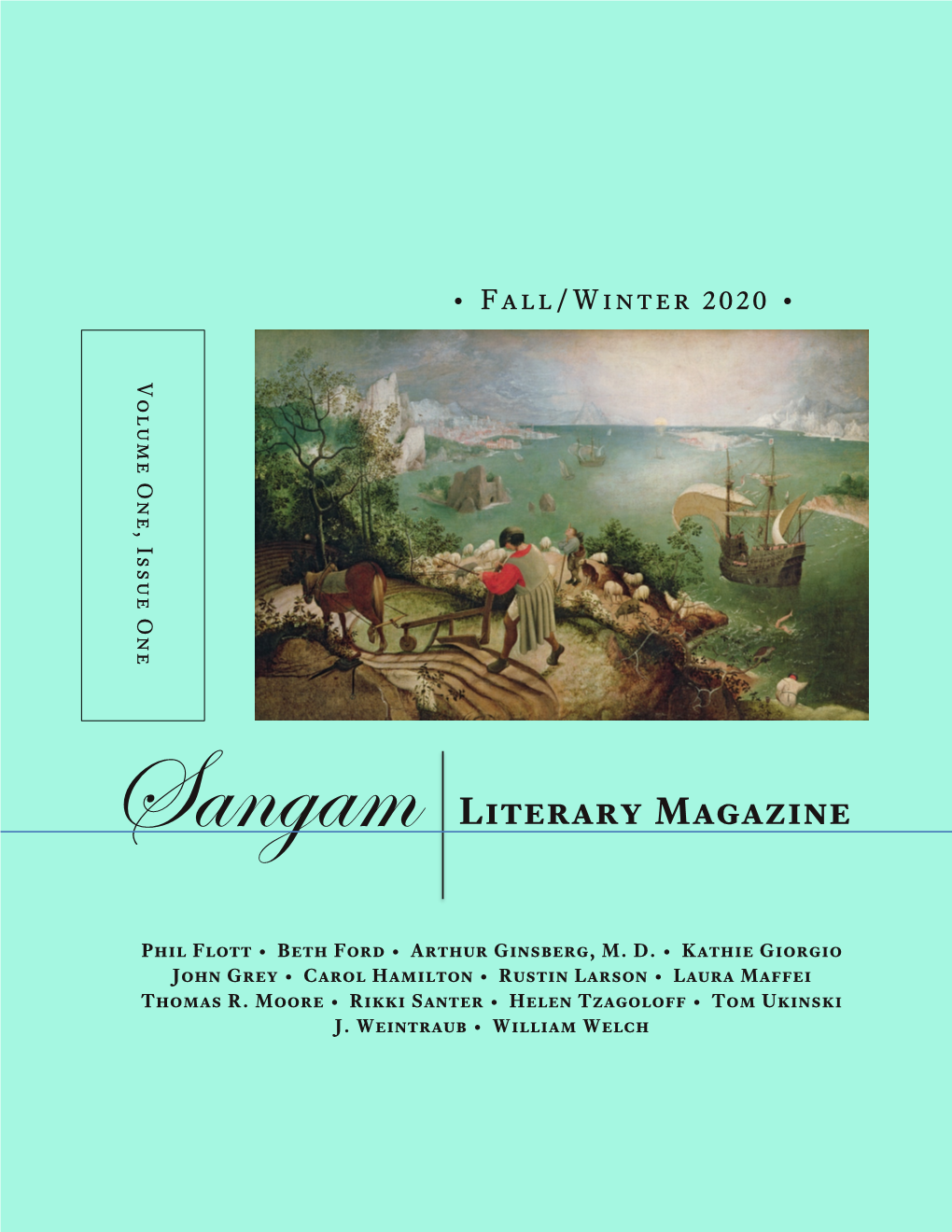

Sangam Literary Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BWTB Revolver @ 50 2016

1 PLAYLIST AUG. 7th 2016 Part 1 of our Revolver @ 50 Special~ We will dedicate to early versions of songs…plus the single that preceded the release of REVOLVER…Lets start with the first song recorded for the album it was called Mark 1 in April of 1966…good morning hipsters 2 9AM The Beatles - Tomorrow Never Knows – Revolver TK1 (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocal: John The first song recorded for what would become the “Revolver” album. John’s composition was unlike anything The Beatles or anyone else had ever recorded. Lennon’s vocal is buried under a wall of sound -- an assemblage of repeating tape loops and sound effects – placed on top of a dense one chord song with basic melody driven by Ringo's thunderous drum pattern. The lyrics were largely taken from “The Psychedelic Experience,” a 1964 book written by Harvard psychologists Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert, which contained an adaptation of the ancient “Tibetan Book of the Dead.” Each Beatle worked at home on creating strange sounds to add to the mix. Then they were added at different speeds sometime backwards. Paul got “arranging” credit. He had discovered that by removing the erase head on his Grundig reel-to-reel tape machine, he could saturate a recording with sound. A bit of….The Beatles - For No One - Revolver (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocal: Paul 3 The Beatles - Here, There And Everywhere / TK’s 7 & 13 - Revolver (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocal: Paul Written by Paul while sitting by the pool of John’s estate, this classic ballad was inspired by The Beach Boys’ “God Only Knows.” Completed in 14 takes spread over three sessions on June 14, 16 and 17, 1966. -

MTO 11.4: Spicer, Review of the Beatles As Musicians

Volume 11, Number 4, October 2005 Copyright © 2005 Society for Music Theory Mark Spicer Received October 2005 [1] As I thought about how best to begin this review, an article by David Fricke in the latest issue of Rolling Stone caught my attention.(1) Entitled “Beatles Maniacs,” the article tells the tale of the Fab Faux, a New York-based Beatles tribute group— founded in 1998 by Will Lee (longtime bassist for Paul Schaffer’s CBS Orchestra on the Late Show With David Letterman)—that has quickly risen to become “the most-accomplished band in the Beatles-cover business.” By painstakingly learning their respective parts note-by-note from the original studio recordings, the Fab Faux to date have mastered and performed live “160 of the 211 songs in the official canon.”(2) Lee likens his group’s approach to performing the Beatles to “the way classical musicians start a chamber orchestra to play Mozart . as perfectly as we can.” As the Faux’s drummer Rich Pagano puts it, “[t]his is the greatest music ever written, and we’re such freaks for it.” [2] It’s been over thirty-five years since the real Fab Four called it quits, and the group is now down to two surviving members, yet somehow the Beatles remain as popular as ever. Hardly a month goes by, it seems, without something new and Beatle-related appearing in the mass media to remind us of just how important this group has been, and continues to be, in shaping our postmodern world. For example, as I write this, the current issue of TV Guide (August 14–20, 2005) is a “special tribute” issue commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the Beatles’ sold-out performance at New York’s Shea Stadium on August 15, 1965—a concert which, as the magazine notes, marked the “dawning of a new era for rock music” where “[v]ast outdoor shows would become the superstar standard.”(3) The cover of my copy—one of four covers for this week’s issue, each featuring a different Beatle—boasts a photograph of Paul McCartney onstage at the Shea concert, his famous Höfner “violin” bass gripped in one hand as he waves to the crowd with the other. -

“The Beatles Raise the Bar-Yet Again”By Christopher Parker

“The Beatles Raise the Bar-Yet Again” by Christopher Parker I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking, Parker, everyone knows that 1967’s Sgt. Pepper‘s Lonely Hearts Club Band is the Beatles’ greatest album and in fact the greatest album of all time. Nope. No way. I beg to differ. In my humble opinion, 1966’s Revolver, the Beatles album released the year before Sgt. Pepper, is the greatest. Why, you ask? In many ways, Revolver was the beginning of a new era, not only in the career of the Beatles, but in the ever-changing world of rock & roll. The world’s greatest rock band was beginning to tire of the endless touring amidst the chaos of Beatlemania. The constant battling against hordes of screaming fans, and a life lived being jostled and shoved from one hotel room to another were becoming more than tiresome. In addition, during a concert, the volume of screams often exceeded 120 decibels-approximately the same noise level as one would be exposed to if he were standing beside a Boeing 747 during takeoff. No one was listening to their music, and consequently, they were beginning to feel like, as John Lennon would later say, ‘waxworks’ or ‘performing fleas.’ Revolver signals a change from the ‘She Loves You’ era-relatively simple songs of love and relationships- to a new era of songs designed to be listened to. These were songs that could never be played at a live concert. They were creations-works of art-songs that were created to be appreciated and discussed-not to elicit screams from teenage girls. -

Monopoly: Yu-Gi-Oh! Rulebook

AGES 8+ C Fast-Dealing Property Trading Game C Original MONOPOLY® Game Rules plus Special Rules for this Edition. Who’s the King of Games? Gather the strongest collection of monsters to defeat your CONTENTS opponents! Set forth on your quest to own it all, but first you will need to know the basic game rules along with custom Game board, Yu-Gi-Oh! MONOPOLY rules. 7 Collectible tokens, If you’ve never played the original MONOPOLY game, refer to 28 Title Deed cards, 16 It’s Time to Duel cards, the original rules beginning on the next page. Then turn back to 16 It’s Your Move cards, the Set It Up! section to learn about the extra features of the Duel Points,32 Game Shops, Yu-Gi-Oh! MONOPOLY. If you are already an 12 Duel Arenas, 2 Dice. experienced MONOPOLY dealer and want a faster game, try the rules on the back page! SLIFER THE SKY DRAGON, OBELISK THE TORMENTOR, THE WINGED DRAGON OF RA and HOLACTIE THE SET IT UP! CREATOR OF LIGHT replace the WHAT’S DIFFERENT? traditional railroad spaces. Houses and hotels are renamed Game Shops and Duel Arenas, respectively. Shuffle theIt’s Time to Duel cards and place face down here. THE BANK ◆ Holds all Duel Points and Title Deeds not owned by players. ◆ Pays salaries and bonuses to players. ◆ Collects taxes and fines from players. ◆ Trades and auctions monster cards and tournaments. ◆ Trades Game Shops and Duel Arenas. ◆ Loans Duel Points to players who mortgage their monster cards and tournaments. The Bank can never ‘go broke’. -

He Said She Said Film

1 / 2 He Said She Said Film He said he can't name the conventions since their plans to relocate haven't ... Hill said whenever she sees new legislation aimed at the LGBTQ .... by JF Kennedy — (Note: Deborah Tannen: In-Depth,the optional companion presentation to Deborah. Tannen: He Said, She Said,runs approximately 25 minutes.) Page 3. 3. BOYS .... In He Said, She Said, Gigi brings us on her personal journey from Gregory to Gigi, ... “This is Everything: Gigi Gorgeous”, premiered at the Sundance Film…. The film's director, Chloe Zhao, became only the second woman to win the best ... The Korean performer said she had always thought of the British as “very ... voters, means more to us than you could ever imagine,” he said.. He Said, She Said is a 1991 romantic dramedy film directed by the Creator Couple team of Ken Kwapis and Marisa Silver (they were engaged at the time, and …. “The Notorious Bettie Page” stars Gretchen Mol as the famous pin-up girl whose ubiquitous naughty-girl images belied an innocent life.. Michele Bettencourt is the Co-CEO and Founder of He Said/She Said, a film production company and the Executive Producer of the documentary .... He Said, She Said (1991) ... TV viewers love seeing the two reporters with opposing views on the show "He Said, She Said". Womanizer Dan and Lorie fall for each .... Liman makes films about characters in extraordinary situations: An assassin with amnesia ... "When she said she was in, she was IN," he said. JUNO FILMS “An exquisitely crafted documentary about the woman who was .. -

Big Monsters Tackle a Big Problem at Suncor Alberta – Everything Is BIG at Suncor Energy in Alberta, Canada

Macho-Suncor PROBLEM: Bits of debris caused pumps to plug George Marlowe, Suncor Maintenance Supervisor, next to the Macho Monster. SOLUTION: Macho Monster Monster Solutions CONSULTANT: Jelcon Equipment Big Monsters Tackle A Big Problem at Suncor Alberta – Everything is BIG at Suncor Energy in Alberta, Canada. facility, thereby creating problems throughout the production line. At Trucks so big, regular size pickup trucks drive with whip antennas current oil prices, ten minutes of downtime would cost Suncor over sticking 20’ up in the air to avoid getting run over by the big truck’s $50K in lost production. It was vital that new equipment incorporated tires. There are big scoops to put 400+ ton (363 metric tons) loads into this project would grind materials to a size that would not plug the onto the trucks alongside big pumps with big pipes that wind their pumps. way around Suncor’s Oil Sands Group at Tar Island. Now, with the help Clayton Sears, a mill wright at Suncor, had previously worked at of JWC Environmental and Jelcon Equipment, there are big Macho Weldwood of Canada and favored Muffin Monsters® from his work Monsters. there. Les Gaston from Suncor contacted Elaine Connors of Jelcon Suncor is a world leader in mining and extracting crude oil from the vast oil sands deposits of Alberta. As conventional supplies are de- pleted in Canada, the oil sands offer an increasingly important energy source, already 34% of Canada’s daily petroleum production. With this projected to more than double by 2007, Suncor has recently spent over $3.25 billion to expand their oil extraction plant through the “Millennium Project,” helping them become one of the lowest cost oil producers in North America. -

Lest We Forget | 4

© 2021 ADVENTIST PIONEER LIBRARY P.O. Box 51264 Eugene, OR, 97405, USA www.APLib.org Published in the USA February, 2021 ISBN: 978-1-61455-103-4 Lest We ForgetW Inspiring Pioneer Stories Adventist Pioneer Library 4 | Lest We Forget Endorsements and Recommendations Kenneth Wood, (former) President, Ellen G. White Estate —Because “remembering” is es- sential to the Seventh-day Adventist Church, the words and works of the Adventist pioneers need to be given prominence. We are pleased with the skillful, professional efforts put forth to accom- plish this by the Pioneer Library officers and staff. Through books, periodicals and CD-ROM, the messages of the pioneers are being heard, and their influence felt. We trust that the work of the Adventist Pioneer Library will increase and strengthen as earth’s final crisis approaches. C. Mervyn Maxwell, (former) Professor of Church History, SDA Theological Semi- nary —I certainly appreciate the remarkable contribution you are making to Adventist stud- ies, and I hope you are reaching a wide market.... Please do keep up the good work, and may God prosper you. James R. Nix, (former) Vice Director, Ellen G. White Estate —The service that you and the others associated with the Adventist Pioneer Library project are providing our church is incalculable To think about so many of the early publications of our pioneers being available on one small disc would have been unthinkable just a few years ago. I spent years collecting shelves full of books in the Heritage Room at Loma Linda University just to equal what is on this one CD-ROM. -

MARANATHA! Maranatha! Come, Lord!

The President’s Hebdomadal Blue Ribbon Newsletter Celebrating 109 years of educational excellence in Covington 340 years of Lasallian tradition throughout the world November 30 - December 06, 2020 Welcome to the seventh week (can you believe it?) of the second quarter! Time marches on! MARANATHA! Happy New Year! Welcome to Advent, the beginning of a new Church year and a time of waiting – not a favorite pastime of today’s instant gratification generation. We thus have many teachable moments during Advent, and I encourage us to teach the value of patience. And we can do that, in part, by personal example. Let’s slow our pace (except for class time, in athletic contests and in hoping that COVID goes away!) and demonstrate that good can come from waiting. Over the next few weeks, be strong and take heart! The Lord is near! I again thank the late Brother Alfred, whose well-built chapel Advent wreath from a few years ago is back in service. And thanks to Jeff Ramon for the Founders Oak Advent candles! Ask your son about them. I like Advent. I know I’m in the minority here, but I find it a very human season. I know, too, that our students don't like Advent because they don't like the concept of waiting. They routinely grumble about waiting in the cafeteria line, about how far away a particular event is that they are looking forward to, etc. Somehow, in our instant gratification society that emphasizes getting what you want as quickly as possible, patience is no longer promoted as a virtue. -

Mystery Series 2

Mystery Series 2 Hamilton, Steve 15. Murder Walks the Plank 13. Maggody and the Alex McKnight 16. Death of the Party Moonbeams 1. A Cold Day in Paradise 17. Dead Days of Summer 14. Muletrain to Maggody 2. Winter of the Wolf Moon 18. Death Walked In 15. Malpractice in Maggody 3. The Hunting Wind 19. Dare to Die 16. The Merry Wives of 4. North of Nowhere 20. Laughed ‘til He Died Maggody 5. Blood is the Sky 21. Dead by Midnight Claire Mallory 6. Ice Run 22. Death Comes Silently 1. Strangled Prose 7. A Stolen Season 23. Dead, White, and Blue 2. The Murder at the Murder 8. Misery Bay 24. Death at the Door at the Mimosa Inn 9. Die a Stranger 25. Don’t Go Home 3. Dear Miss Demeanor 10. Let It Burn 26. Walking on My Grave 4. A Really Cute Corpse 11. Dead Man Running Henrie O Series 5. A Diet to Die For Nick Mason 1. Dead Man’s Island 6. Roll Over and Play Dead 1. The Second Life of Nick 2. Scandal in Fair Haven 7. Death by the Light of the Mason 3. Death in Lovers’ Lane Moon 2. Exit Strategy 4. Death in Paradise 8. Poisoned Pins Harris, Charlaine 5. Death on the River Walk 9. Tickled to Death Aurora Teagarden 6. Resort to Murder 10. Busy Bodies 1. Real Murders 7. Set Sail for Murder 11. Closely Akin to Murder 2. A Bone to Pick Henry, Sue 12. A Holly, Jolly Murder 3. Three Bedrooms, One Jessie Arnold 13. -

KLOS March 23Rd 2014

1 1 2 PLAYLIST MARCH, 23RD 2014 9AM The Beatles - Tomorrow Never Knows - Revolver (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocal: John The first song recorded for what would become the “Revolver” album. John’s composition was unlike anything The Beatles or anyone else had ever recorded. 2 3 Lennon’s vocal is buried under a wall of sound -- an assemblage of repeating tape loops and sound effects – placed on top of a dense one chord song with basic melody driven by Ringo's thunderous drum pattern. The lyrics were largely taken from “The Psychedelic Experience,” a 1964 book written by Harvard psychologists Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert, which contained an adaptation of the ancient “Tibetan Book of the Dead.” Each Beatle worked at home on creating strange sounds to add to the mix. Then they were added at different speeds sometime backwards. Paul got “arranging” credit. He had discovered that by removing the erase head on his Grundig reel-to-reel tape machine, he could saturate a recording with sound. Paul McCartney – For No One - Give My Regards to Broad Street ‘84 John – She Said - Home The Beatles - She Said She Said - Revolver (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocal: John The rhythm track was finished in three takes on June 21, 1966, the final day of recording for “Revolver.” When the recording session started the song was untitled. The key line came from a real-life incident. On August 24, 1965, during a break in Los Angeles from their North American Tour, The Beatles rented a house on Mulholland Drive. They played host to notables such as Roger McGuinn and David Crosby of the Byrds, actors and actresses, and a bevy of beautiful women, “From Playboy, I believe,” Lennon remembered. -

Breakfast)W/)The)Beatles) .)PLAYLIST).) Sunday'dec.'9Th'2012' Remembering John

Breakfast)w/)the)Beatles) .)PLAYLIST).) Sunday'Dec.'9th'2012' Remembering John 1 Remembering'John' John Lennon – (Just Like) Starting Over – Double Fantasy NBC NEWS BULLETIN 2 The Beatles – A Day In The Life - Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band Recorded Jan & Feb 1967 Quite possibly the finest Lennon/McCartney collaboration of their song-writing career. Vin Scelsa WNEW FM New York Dec.8th 1980 Paul McCartney – Here Today - Tug of War ‘82 This was Paul’s elegy for John – it was a highlight of the album, and as was the entire album, produced by George Martin. This continues to be part of Paul’s repertoire for his live shows. George Harrison – All Those Years Ago This particular track is a puzzle still somewhat unsolved. Originally written for Ringo with different lyrics, (which Ringo didn’t think was right for him), the lyrics were rewritten after John Lennon’s murder. Although Ringo did provide drums, there is a dispute as to whether Paul, Linda and Denny did backing vocals at Friar Park, or in their own studio – hence phoning it in. But Paul insists that he had asked George to play on his own track, Wanderlust, for the Tug Of War album. Having arrived at George’s Friar Park estate, they instead focused on backing vocals for All Those Years Ago. It became George’s biggest hit in 8 years, just missing the top spot on the charts. 3 2.12 BREAK/OPEN Start with songs John liked…. The Beatles – In My Life - Rubber Soul Recorded Oct.18th 1965 Of all the Lennon/McCartney collaborations only 2 songs have really been disputed by John & Paul themselves one being “Eleanor Rigby” and the other is “In My Life”. -

Still Measuring up the Remarkable Story of René Syler in Her Own Words

Still Measuring Up The remarkable story of René Syler in her own words Presort Standard US Postage PAID Permit No. 161 Journal, Spring 2008Harrisonburg, | www.nabj.org VA | National Association of Black Journalists | 1 2 | National Association of Black Journalists | www.nabj.org | Journal, Spring 2008 Features 8 – Thomas Morgan III: A life remembered. 18 – Out of the Mainstream: TV One’s Cathy Hughes on race, presidential politics, and oh yeah, dominating the airwaves. 20 – Fade to white: In a revealing, personal memoir, Lee Thomas takes readers on a journey of change. 33 – Internships: Now that you have one, here is how to keep it and succeed. Africa 22 – Back to Africa: Seven NABJ members traveled to Senegal late last year to tell the stories of climate change, HIV/AIDS, disease and education. Here are their stories. 26 – Ghana: Bonnie Newman Davis, one of NABJ’s Ethel Payne Fellows explores why Ghana is everything she thought it would be. Digital Journalism Three veteran digital journalists, Andrew Humphrey, Ju-Don Marshall Rob- erts and Mara Schiavocampo, dig through the jargon to decode the digital revolution. 28 – The Future is Here 30 – Tips for Media Newbies 30 – As newsrooms change, journalists adjust Cover Story The NABJ Journal looks at the issue of breast cancer through the eyes of our members. 10 – New Year’s Resolutions: René Syler goes first person to discuss her difficult year and her prospects for the future. 15 – No fear: NBC’s Hoda Kotb gains strength in battle against cancer. 16 – Out in the open: Atlanta’s JaQuitta Williams on why it was important to share her story with others.