From Technology Studies to Sound Studies: How Materiality Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vista USD News

University of San Diego Digital USD USD Vista USD News 2-2-1984 Vista: February 2, 1984 University of San Diego Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/vista Digital USD Citation University of San Diego, "Vista: February 2, 1984" (1984). USD Vista. 925. https://digital.sandiego.edu/vista/925 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the USD News at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in USD Vista by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF SAN DIEGO •.t- ^ CHE GO, i.«- c / Vol. XXII No. 14 February 2, 1984 T.G.'s: Battle Of The Beers by Shen Hirsch when ETK accepted the ASB's solved the needed sponsorship AK Psi on the other hand felt was not my fault. I have a stand For the first time in USD his offer to sponsor the Flanigan's. but added a great deal of credibil students should be given an alter ard procedure in which 1 list all tory the students will be given the ETK, Elman Tappa Kegga, was ity to ETK. native to Flanigan's. The popula the free ads on a log sheet and the advantage of a T.G. every Friday. founded by Ed DeMerlier, Vince When AK Psi proposed an tion of student participation had paying ads on another. When ETK, AK Psi and AMA have Kasperick, Tom Ehmann and addition to the agenda ETK was already notably declined from there are too many paying ads the now collaborated to present a Mike Harder as a response to the enraged. -

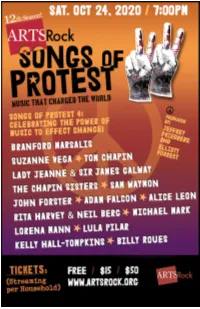

Songs-Of-Protest-2020.Pdf

Elliott Forrest Dara Falco Executive & Artistic Director Managing Director Board of Trustees Stephen Iger, President Melanie Rock, Vice President Joe Morley, Secretary Tim Domini, Treasurer Karen Ayres Rod Greenwood Simon Basner Patrick Heaphy David Brogno James Sarna Hal Coon Lisa Waterworth Jeffrey Doctorow Matthew Watson SUPPORT THE ARTS Donations accepted throughout the show online at ArtsRock.org The mission of ArtsRock is to provide increased access to professional arts and multi-cultural programs for an underserved, diverse audience in and around Rockland County. ArtsRock.org ArtsRock is a 501 (C)(3) Not For-Profit Corporation Dear Friends both Near and Far, Welcome to SONGS OF PROTEST 4, from ArtsRock.org, a non- profit, non-partisan arts organization based in Nyack, NY. We are so glad you have joined us to celebrate the power of music to make social change. Each of the first three SONGS OF PROTEST events, starting in April of 2017, was presented to sold-out audiences in our Rockland, NY community. This latest concert, was supposed to have taken place in-person on April 6th, 2020. We had the performer lineup and songs already chosen when we had to halt the entire season due to the pandemic. As in SONGS OF PROTEST 1, 2 & 3, we had planned to present an evening filled with amazing performers and powerful songs that have had a historical impact on social justice. When we decided to resume the series virtually, we rethought the concept. With so much going on in our country and the world, we offered the performers the opportunity to write or present an original work about an issue from our current state of affairs. -

Magic Man Fourstardave Tosparecord Voodoo Songaddsgrade1 Sunday, August12,2018

Year 18 • No. 17 Sunday, August 12, 2018 The aratoga Saratoga’s Daily Racing Newspaper since 2001 Magic Man Voodoo Song adds Grade 1 Fourstardave to Spa record ENTRIES & HANDICAPPING INSPECTOR LYNLEY WINS LURE SUE’S FORTUNE CLIMBS ADIRONDACK Tod Marks Tod 2 THE SARATOGA SPECIAL SUNDAY, AUGUST 12, 2018 here&there...at Saratoga Presented by Neuman Insurance ............................ equineinsurance.com BY THE NUMBERS 21,500: Projected Thoroughbred foal crop for 2019 by The Jockey Club, holding steady on 2018 projections. It was 38,365 in 2005. 1-9: Odds on Gunnevera when he won an allowance prep for Saratoga’s Woodward (to be run Sept. 1) at Gulfstream Park Friday. 66: Round Table Conferences on Matters Pertaining to Racing hosted by The Jockey Club after today’s event at the Gideon Putnam Hotel. The conference starts at 10 a.m. and can be seen on TVG2 and tvg.com as well as via live stream at jockeyclub.com. Presentations include Chris Pollak of Google on digital marketing, McKinsey and Associates on recom- mended growth initiatives for racing and more. NAMES OF THE DAY Brucia La Terra, fifth race.We have a new leader for Name of the Meet. Named by her breeders Sallyellen and Hugh Hurst, the 2-year-old filly is by El Padrino (The Godfather in Italian) out of Happy Refrain (whose dam is Sad Refrain). The Maryland-bred’s name trans- lates to Burning The Earth, the title of a song from the movie The Godfather. Feedback, sixth race. Klaravich Stable’s 2-year-old filly is out of Honest Answer. -

Arizona 500 2021 Final List of Songs

ARIZONA 500 2021 FINAL LIST OF SONGS # SONG ARTIST Run Time 1 SWEET EMOTION AEROSMITH 4:20 2 YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG AC/DC 3:28 3 BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY QUEEN 5:49 4 KASHMIR LED ZEPPELIN 8:23 5 I LOVE ROCK N' ROLL JOAN JETT AND THE BLACKHEARTS 2:52 6 HAVE YOU EVER SEEN THE RAIN? CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL 2:34 7 THE HAPPIEST DAYS OF OUR LIVES/ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PART TWO ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PART TWO 5:35 8 WELCOME TO THE JUNGLE GUNS N' ROSES 4:23 9 ERUPTION/YOU REALLY GOT ME VAN HALEN 4:15 10 DREAMS FLEETWOOD MAC 4:10 11 CRAZY TRAIN OZZY OSBOURNE 4:42 12 MORE THAN A FEELING BOSTON 4:40 13 CARRY ON WAYWARD SON KANSAS 5:17 14 TAKE IT EASY EAGLES 3:25 15 PARANOID BLACK SABBATH 2:44 16 DON'T STOP BELIEVIN' JOURNEY 4:08 17 SWEET HOME ALABAMA LYNYRD SKYNYRD 4:38 18 STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN LED ZEPPELIN 7:58 19 ROCK YOU LIKE A HURRICANE SCORPIONS 4:09 20 WE WILL ROCK YOU/WE ARE THE CHAMPIONS QUEEN 4:58 21 IN THE AIR TONIGHT PHIL COLLINS 5:21 22 LIVE AND LET DIE PAUL MCCARTNEY AND WINGS 2:58 23 HIGHWAY TO HELL AC/DC 3:26 24 DREAM ON AEROSMITH 4:21 25 EDGE OF SEVENTEEN STEVIE NICKS 5:16 26 BLACK DOG LED ZEPPELIN 4:49 27 THE JOKER STEVE MILLER BAND 4:22 28 WHITE WEDDING BILLY IDOL 4:03 29 SYMPATHY FOR THE DEVIL ROLLING STONES 6:21 30 WALK THIS WAY AEROSMITH 3:34 31 HEARTBREAKER PAT BENATAR 3:25 32 COME TOGETHER BEATLES 4:06 33 BAD COMPANY BAD COMPANY 4:32 34 SWEET CHILD O' MINE GUNS N' ROSES 5:50 35 I WANT YOU TO WANT ME CHEAP TRICK 3:33 36 BARRACUDA HEART 4:20 37 COMFORTABLY NUMB PINK FLOYD 6:14 38 IMMIGRANT SONG LED ZEPPELIN 2:20 39 THE -

Crazy on Them: Heart by Heart Returns to the Taste by Brian Soergel Edmonds, WA Edmondsbeacon.Com

8/11/2016 Crazy on them: Heart by Heart returns to the Taste By Brian Soergel Edmonds, WA EdmondsBeacon.com Crazy on them: Heart by Heart returns to the Taste Spinoff band features members from local high schools By Brian Soergel | Aug 11, 2016 What’s your favorite Heart song? “Barracuda”? “Crazy on You”? “Magic Man?” Chances are you’ll hear them all when Heart by Heart returns to A Taste of Edmonds 7 p.m. Saturday on the main stage. But bassist Steve Fossen, an original member of Heart who formed Heart by Heart, said there is one particular tune Courtesy of: Janine Harles that really gets the crowd going, and Heart by Heart performs at a previous A Taste of Edmonds. it’s not a rocker – it’s the power ballad “Alone.” “That happens to be the very first Heart song that Somar ever learned,” said Fossen, referring to lead singer Somar Macek, who graduated from Meadowdale High School. “It always gets a strong response. It often brings people to their feet.” Somar sings because, as you might have guessed, sisters Ann and Nancy Wilson are not in the band. Which is not a “tribute” band, by the way. “Heart by Heart is technically a spinoff band, and has evolved into an authentic throwback and tribute to the legacy and songs of the '70s and '80s,” said Fossen who, along with bandmember and drummer Michael Derosier – who graduated from the old Woodway High School – was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as part of Heart in 2013. -

Dr. Earl Davis Is Always Busy with University of Texas at Austin and Completed His One Task Or Another

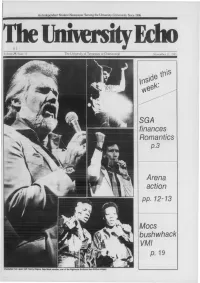

An Independent Student Newspaper Serving the University Community Since 1906 The University Echo <?3 • .-. W Volume/?f?/Issue The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga November II, 1983 SGA finances Romantics p.3 Arena action pp. 12-13 Mocs bushwhack VMI p. 19 Clockwise Irom upper left: Kenny Rogers, Gap Band member, one of the Righteous Brothers, New Edition singers. "Our Personnel Touch guarantees you quality service. Thanks tn Pi tWa Phi f„r rhi, pi.-t..,-,- I'II niri-fl ni-n rimis-.Li ^^'inrlniH Echo News 2 The Echo/November 11, 1983 No pay raise this year UTC faculty salaries below average By Sandy Fye Echo News Editor UTC will need $903,600 to bring faculty salaries up 155 and over stay, then there's no room for new faculty. to Southern Region Education Board (SREB) And we can't afford to retire. averages, according to information compiled by Dave To reach 1982-1983 fiscal year faculty pay "On the whole, I think we've got the best teaching Larson, vice chancellor of administration and finance, averages: faculty in the state," continued Printz. "But it makes in his "Planning for Excellence" report. 66 professors need an average of $2755 each you sort of sad that you can't afford to send your Because report figures were based on 1982-83 109 associate professors need an average of children somewhere else, so they won't be burdened SREB averages, much more money will be necessary $2330 each by having a parent on campus." to raise the salary level to the current average as the 85 assistant professors need an average of $2798 Printz said many former UTC faculty and staff UTC faculty did not receive pay raises for 1983 84, for each members have relocated to other jobs or out of the cost-of-living or otherwise. -

Global Music Pulse: the POP CATALOG Poser's Collective

$5.95 (U.S.), $6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) IIII111II1 II I 1I1II,1IIII 1I,1II1J11 III 111IJ1IInIII #BXNCCVR 3-DIGIT 908 #90807GEE374EM002# BLBD 779 A06 B0128 001 033002 2 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO, AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT APRIL 14, 2001 COMMENTAR Y SENATE NEARING TACKLES MUSICNET PROPOSAL RAISES How To Revive INTERNET MUSIC ISSUES QUESTIONS OF FAIRNESS BY BILL HOLLAND The Senate hearing focused Singles Market BY FRANK SAXE goes into the label's pockets. WASHINGTON, D.C.-Of the many mainly on the issues of licensing NEW YORK-While the music in- Streaming media developer Real- issues presented by the 14- witness product from labels and music pub- BY MICHAEL ELLIS dustry was busy touting its new Networks is teaming with Warner panel at the Senate Judiciary Com- lishers, but no lawmakers hinted at The collapse of the U.S. sin- MusicNet digital download Music Group (WMG), mittee hearing April 3 to examine the legislation to help solve the many gles market-down more than initiative, critics were call- Inapster BMG Entertainment, growing pains marketplace 40% this year so far -is terri- ing into question the team- and the EMI Group to and problematic problems. In ble for the U.S. record indus- ing of three -fifths of the create the online sub- implications of fact, commit- try. The cause of the decline is music business into a sin- scription music service, online music, tee chairman not a lack of interest among gle entity that may one which is set to bow this lawmakers Sen. -

Here Are Things I Needed to Say.” the Album Was Released in the U.S

BURT BACHARACH Biography Six decades into one of songwriting’s most successful and honored careers – marked by 48 Top 10 hits, nine #1 songs, more than 500 compositions and a landmark 49-year run on the charts, Burt Bacharach’s music continues to set industry records and creative standards. “At This Time,” his 2005 album, which won the Grammy for Best Pop Instrumental Album, breaks new ground with Bacharach’s first-ever lyrical collaborations, supplementing the melodies which reflect the pioneering Bacharach sound. He says it is the “most-passionate album” of his career as “At This Time” marks the first time Bacharach takes on social and political issues in his music. Bacharach’s global audiences span several generations, and he is viewed as the unique combination of one of the greatest composers of all time and the ultra-cool cult hero of the contemporary music set who often has several songs on various music charts in many countries simultaneously. His many concerts are SRO, as he tours the United States and the world conducting orchestras and with his own musicians and singers performing his music. Along with Bob Dylan, John Lennon and Paul McCartney and Paul Simon, Bacharach is a legend of popular music. A recipient of three Academy Awards and seven Grammy Awards (including the 1997 Trustees Award with collaborator Hal David), he revolutionized the music of the 1950s and 60s and is regularly bracketed with legendary names, ranging from Cole Porter, to Sir George Martin, as one of a handful of visionaries who pioneered new forms of music from the second half of the 20th Century and into the 21st Century. -

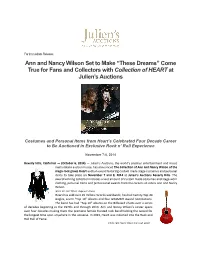

Ann and Nancy Wilson Set to Make “These Dreams” Come True for Fans and Collectors with Collection of HEART at Julien’S Auctions

For Immediate Release: Ann and Nancy Wilson Set to Make “These Dreams” Come True for Fans and Collectors with Collection of HEART at Julien’s Auctions Costumes and Personal Items from Heart’s Celebrated Four Decade Career to Be Auctioned in Exclusive Rock n’ Roll Experience November 7-8, 2014 Beverly Hills, California — (October 6, 2014) — Julien’s Auctions, the world’s premier entertainment and music memorabilia auction house, has announced The Collection of Ann and Nancy Wilson of the mega-rock group Heart auction event featuring custom made stage costumes and personal items to take place on November 7 and 8, 2014 at Julien’s Auctions Beverly Hills. The award-winning collection includes a vast amount of custom made costumes and stage worn clothing, personal items and professional awards from the careers of sisters Ann and Nancy Wilson. (photo left: Ann Wilson stage-worn dress) Heart has sold over 35 million records worldwide, has had twenty Top 40 singles, seven “Top 10” albums and four GRAMMY Award nominations. The band has had “Top 10” albums on the Billboard charts over a series of decades beginning in the 1970’s and through 2010. Ann and Nancy Wilson’s career spans over four decades making them the premiere female fronted rock band holding the record for the longest time span anywhere in the universe. In 2013, Heart was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. (photo right: Nancy Wilson tour used guitar) Ann and Nancy Wilson set the stage for all female rockers when they first formed the band in 1974. -

Page 1 TEACHER, TEACHER .38 SPECIAL I GO BLIND 54-40

Page 1 TEACHER, TEACHER .38 SPECIAL I GO BLIND 54-40 OCEAN PEARL 54-40 Make Me Do) ANYTHING YOU WANT A FOOT IN COLD WATER HAND IN MY POCKET ALANIS MORISSETTE HEAD OVER FEET ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC ALANIS MORISSETTE THANK YOU ALANIS MORISSETTE UNINVITED ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU LEARN ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW ALANIS MORISSETTE BLACK VELVET ALANNAH MYLES LOVE IS ALANNAH MYLES LOVER OF MINE ALANNAH MYLES SONG INSTEAD OF A KISS ALANNAH MYLES STILL GOT THIS THING ALANNAH MYLES FANTASY ALDO NOVA MORE THAN WORDS CAN SAY ALIAS HELLO HURRAY ALICE COOPER BIRMINGHAM AMANDA MARSHALL DARK HORSE AMANDA MARSHALL FALL FROM GRACE AMANDA MARSHALL LET IT RAIN AMANDA MARSHALL BABY I LOVE YOU ANDY KIM BE MY BABY ANDY KIM HOW'D WE EVER GET THIS WAY? ANDY KIM I FORGOT TO MENTION ANDY KIM ROCK ME GENTLY ANDY KIM SHOOT 'EM UP BABY ANDY KIM BAD SIDE OF THE MOON APRIL WINE ENOUGH IS ENOUGH APRIL WINE I WOULDN'T WANT TO LOSE YOUR LOVE APRIL WINE I'M ON FIRE FOR YOU BABY APRIL WINE JUST BETWEEN YOU AND ME APRIL WINE LIKE A LOVER, LIKE A SONG APRIL WINE OOWATANITE APRIL WINE ROCK AND ROLL IS A VICIOUS GAME APRIL WINE ROLLER APRIL WINE SAY HELLO APRIL WINE SIGN OF THE GYPSY QUEEN APRIL WINE TONITE IS A WONDERFUL TIME APRIL WINE YOU COULD HAVE BEEN A LADY APRIL WINE YOU WON'T DANCE WITH ME APRIL WINE BLUE COLLAR BACHMAN-TURNER OVERDRIVE GIMME YOUR MONEY PLEASE BACHMAN-TURNER OVERDRIVE HEY YOU BACHMAN-TURNER OVERDRIVE LET IT RIDE BACHMAN-TURNER OVERDRIVE Page 2 LOOKIN' OUT FOR #1 BACHMAN-TURNER OVERDRIVE ROLL ON DOWN THE HIGHWAY BACHMAN-TURNER OVERDRIVE TAKIN' -

2018 Street Performer Series Performer Bios

2018 Street Performer Series Performer Bios Balloon Twisters The Balloon Guy Jim Perry, also known as “The Balloon Guy,” has been twisting balloons for more than 25 years. He is a graduate of the world famous Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Clown College. He can make more than 100 different balloon animals, swords, flowers and hats. Chau “Chuckles” Le-Tran Chuckles can twist balloons into hundreds of shapes, including flowers, animals, plants, helicopters, wands, swords and much more. He caters to kids of all ages and even adults who are kids at heart. Chuckles has performed at events all across Michigan and is excited to return to the Street Performer Series this year. Dan the Magic Man Dan Mutschler is a self-taught balloon artist who performs regularly at birthday parties, scouting events, art fairs and at Logan’s Roadhouse. He also volunteers weekly at several nursing homes, performing card tricks and visiting with elderly residents. Caricature Artists and Graphic Artists Caricatures by Britta Britta Lindemulder is Holland native who holds a degree in Illustration from Grand Valley State University. She first learned to draw caricatures in 2007 during a summer job at Michigan’s Adventure and loves seeing the smiles on people's faces when she hands them their custom drawing. Caricatures by Corey Ruffin Corey is a world-renowned caricaturist who has drawn faces in 48 states and on 4 different continents. Corey emphasizes humor and comedy in his fanciful and exaggerated drawings. He is the fastest caricature artist in the nation and onlookers watch in amazement as he whips out a portrait in less than a minute! Circus Acts Bangarang Circus Bangarang Circus Arts is a collective of performance artists who share a passion for all things circus and a desire for community. -

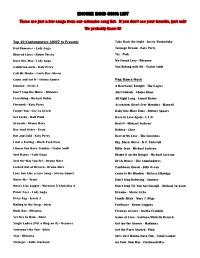

ENCORE BAND SONG LIST These Are Just a Few Songs from Our Extensive Song List

ENCORE BAND SONG LIST These are just a few songs from our extensive song list. If you don’t see your favorite, just ask! We probably know it! Top 40/Contemporary (2007 to Present) Take Back the Night - Justin Timberlake Bad Romance - Lady Gaga Teenage Dream - Katy Perry Blurred Lines - Robin Thicke Try - Pink Born this Way - Lady Gaga We Found Love - Rhianna California Girls - Katy Perry You Belong with Me - Taylor Swift Call Me Maybe - Carly Rae Jebsen Come and Get It - Selena Gomez Pop/Dance/Rock Domino - Jessie J A Heartache Tonight - The Eagles Don’t Stop the Music - Rhianna Ain’t Nobody - Chaka Khan Everything - Michael Buble All Night Long - Lionel Richie Firework - Katy Perry Ascension (Don’t Ever Wonder) - Maxwell Forget You - Cee Lo Green Baby One More Time - Britney Spears Get Lucky - Daft Punk Back in Love Again - L.T.D. Grenade - Bruno Mars Beat It - Michael Jackson’ Hey Soul Sister - Train Believe - Cher Hot and Cold - Katy Perry Best of My Love - The Emotions I Got a Feeling - Black Eyed Peas Big, Black Horse - K.T. Tumstall I Knew You Were Trouble - Taylor Swift Billie Jean - Michael Jackson Just Dance - Lady Gaga Blame it on the Boogie - Michael Jackson Just the Way You Are - Bruno Mars Brick House - The Commodores Locked Out of Heaven - Bruno Mars Caribbean Queen - Billy Ocean Love You Like a Love Song - Selena Gomez Come to My Window - Melissa Ethridge Marry Me - Train Don’t Stop Believing - Journey Moves Like Jagger - Marroon 5/Christina A. Don’t Stop Til’ You Get Enough - Michael Jackson Poker Face - Lady Gaga Dreams - Stevie Nicks Price Tag - Jessie J Family Affair - Mary J.