Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NO. Title Artist Label 1 04.00 the Toys What the Duck 2 ๙

NO. Title Artist Label 1 04.00 The Toys What The Duck 2 ๙ ประกาศิต แสนปากดี (ต่าย อภิรมย์) อิสระ 3 747 PC 0832/676 อิสระ 4 1917 Summer Dress Panda Records 5 1984 Secret Tea Party อิสระ 6 134340 The Photo Sticker Machine feat. ริค วชิรปิลันธน์ อิสระ 7 #ขอโทษจริงๆ Basket Band อิสระ 8 #คนเหงา2018 ปนัสฐ์ นาครําไพ (Point) feat. มารุต ชื�นชมบูรณ์ (Art) SRP 9 #ความรักก็เช่นกัน อภิวัชร์ เอื�อถาวรสุข (Stamp) Love iS 10 #อย่าให้ฉันคิด Room 39 Love is Bec Tero Music 11 (๑) ดูดาว / Stargazing วิมุตติ Bird Sound Record 12 (Intentional) Fall The 10th Saturday Five Four Draft 13 (อย่าทําให้ฉัน) ฝันเก้อ วิตดิวัต พันธุรักษ์ (ต็อง) feat. วินัย พันธุรักษ์ Warner Music 14 ... (Reset) อินธนูและพู่ถุงเท้า Minimal Records 15 … ก่อน Supersub สนามหลวง 16 0.5 sec. PC 0832/676 อิสระ 17 04.00 A.M. Solitude Is Bliss Minimal Records 18 04.00 A.M. [Light Version] Solitude Is Bliss Minimal Records 19 1.9 มิติ Two Million Thanks SO::ON Dry Flower 20 11.15 AM Parim Comet Record 21 12/12 (Once) [No Signal Input 5] Sirimongkol No Signal Input 22 13 ตุลา หนึ�งทุ่มตรง ธเนศ วรากุลนุเคราะห์ อิสระ 23 16090 / หมื�นไมล์ TELEx TELEXs Wayfer Records 24 18+ / สิบแปดบวก Chanudom feat. ธนิดา ธรรมวิมล (ดา Endorphine) What The Duck 25 201.1 KM. สิริพรไฟกิ�ง Summer Disc 26 213 [คณะlพวงlรักlเร่] ประกาศิต แสนปากดี (ต่าย อภิรมย์) อิสระ 27 -30 (Minus Thirty) X0809 อิสระ 28 30 กุมภาพันธ์ / febuary [No Signal Input 5] Sirimongkol No Signal Input 29 30+ แล้วไง? พุทธธิดา ศิระฉายา (อี�ฟ) สหภาพดนตรี 30 ๓๖๐ องศา Sitta อิสระ 31 365 วันกับเครื�องบินกระดาษ BNK48 BNK48 32 3rd Cloud Behind อิสระ 33 4388 (So Long) เจี�ยป้าบ่อสื�อ อิสระ 34 5 O' Clock Away The Ways อิสระ 35 500 กม. -

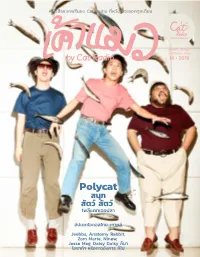

By Cat Radio 16 • 2019

หนังสือแจกฟรีของ Cat Radio ทีหวังว่าจะออกทุกเดือน่ แจกฟรี มีไม่เยอะ เก็บไว้เหอะ ...เมียว้ by Cat Radio 16 • 2019 Polycat สนุก สัตว์ สัตว์ โพลีแคทเจอปลา อัปเดตไอดอลไทย-เกาหลี Jeebbs, Anatomy Rabbit, Zom Marie, Ninew, Jesse Meg, Daisy1 Daisy ก็มา โอซาก้า หรือดาวอังคาร ก็ไป Undercover สืบจากปก by _punchspmngknlp คุณยาย บ.ก. ของเรา เสนอปกเล่มนี้ตอนทุกคนก�าลังยุ่งกับการ เตรียมงาน Cat Tshirt 6 แล้วอาศัยโอกาสลงมือท�าเลย จึงไม่มีโมเมนต์ การอภิปรายหรือเห็นชอบจากใคร อย่าได้ถามถึงความชอบธรรมใดๆ ว่า ท�าไมปกเค้าแมวกลับมาเป็นศิลปินชายอีกแล้ว (วะ) แต่ชีวิตไม่สิ้นก็ดิ้นกันไป เราได้เสนอปกรวมดาวไอดอลชุดแซนตี้ ช่วง คริสมาสต์ไปแล้ว เราสัญญาว่าเราจะไฟต์ ให้ก�าลังใจเราด้วย แต่ถ้าไม่ได้ก็ คือไม่ได้ จบ รักนะ (O,O) 2 3 เข้าช่วงท้ายของพุทธศักราช 2562 แล้ว เราจึงชวนวงดนตรีที่เพิ่งมีคอนเสิร์ตใหญ่ครั้งแรก 2 วงมาขึ้น ในฐานะผู้สังเกตการณ์ นับเป็นปีที่ ปกเค้าแมวฉบับเดียวกัน แม้จะต่างทั้งชั่วโมงบินในการท�างาน น่าชื่นใจของหลายศิลปินที่มีคอนเสิร์ต สไตล์ดนตรี สังกัด แต่เราคิดว่าทั้งคู่คงมีความสุขในการใช้เวลา ใหญ่/คอนเสิร์ตแรก ตลอดจนการไปเล่น ร่วมกับแฟนเพลงในคอนเสิร์ตเต็มรูปแบบของตนเอง รวมถึงการ CAT Intro ในเวที/เทศกาลดนตรีนานาชาติ หรือมี ท�าอะไรหลายอย่างที่น่าสนุกอย่างมาก พูดแบบกันเองก็สนุกสัสๆ RADIO ผลงานใดๆ ที่แฟนเพลงต่างสนับสนุน เราเลยจัดสัตว์มาถ่ายรูปขึ้นปกกับพวกเขาด้วยในคอนเซปต์ “สนุก อุดหนุน และภาคภูมิใจไปด้วย สัตว์ สัตว์” แต่อย่างที่เคยได้ยินกันว่าท�างานกับสัตว์ก็ไม่ง่าย ภาพ DJ Shift อาจเปรียบดังรางวัลหรือก�าลังใจ ที่ได้จึงมีทั้งสัตว์จริงและไม่จริง แต่กล่าวด้วยความสัตย์จริงว่าเรา จากการท�างานหนัก/ทุ่มเทให้สิ่งที่รัก สนุกกับการท�างานกับทั้งสองวง และหวังว่าบทสนทนาที่ปรากฏจะ -

Program Studi Ilmu Komunikasi Fakultas Ilmu Sosial Dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Sumatera Utara

KONSTRUKSI CITRA GRUP IDOLA JEPANG AKB48 DALAM PROGRAM ACARA TELEVISI PRODUCE 48 (Analisis Framing Robert Entman Mengenai Citra Grup Idola Jepang AKB48 pada Program Acara Televisi Korea Selatan Produce 48 oleh MNET) SKRIPSI ALDO ARINATA NAINGGOLAN 150904068 Public Relations PROGRAM STUDI ILMU KOMUNIKASI FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2019 Universitas Sumatera Utara KONSTRUKSI CITRA GRUP IDOLA JEPANG AKB48 DALAM PROGRAM ACARA TELEVISI PRODUCE 48 (Analisis Framing Robert Entman Mengenai Citra Grup Idola Jepang AKB48 pada Program Acara Televisi Korea Selatan Produce 48 oleh MNET) SKRIPSI Diajukan sebagai salah satu syarat untuk memperoleh gelar sarjana Program Strata-1 pada Program Studi Ilmu Komunikasi Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Sumatera Utara ALDO ARINATA NAINGGOLAN 150904068 Public Relations PROGRAM STUDI ILMU KOMUNIKASI FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2019 i Universitas Sumatera Utara LEMBAR PERSETUJUAN Skripsi ini ditujukan untuk dipertahankan oleh: Nama : Aldo Arinata Nainggolan NIM : 150904068 Judul Skripsi : “Konstruksi Citra Grup Idola Jepang AKB48 dalam Program Acara Televisi Produce 48 (Analisis Framing Robert Entman Mengenai Citra Grup Idola Jepang AKB48 pada Program Acara Televisi Korea Selatan Produce 48 oleh Mnet)” Dosen Pembimbing Ketua Departemen Munzaiman Masril S.Sos., M.I.Kom Dra. Dewi Kurniawati, M.Si., Ph.D NIP. 198011072006042002 NIP. 196505241989032001 Dekan FISIP USU Dr. Muryanto Amin S.Sos, M.Si NIP. 19740930 2005011002 -

Social Construction Fandom As Cultural Industry Marketing of JKT 48 Fan Group / 257 - 266

Ahmad Mulyana; Rizki Briandana; Dwi Anggraini Puspa Ningrum / Social Construction Fandom as Cultural Industry Marketing of JKT 48 Fan Group / 257 - 266 ISSN: 2089-6271 | e-ISSN: 2338-4565 | https://doi.org/10.21632/irjbs Vol. 12 | No. 3 Social Construction Fandom as Cultural Industry Marketing of JKT 48 Fan Group Ahmad Mulyana, Rizki Briandana, Dwi Anggraini Puspa Ningrum Universitas Mercu Buana, Jl. Meruya Selatan, Kec. Kembangan, Jakarta Barat, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta 11650 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The aim of this research is to analyzed the social construction of marketing communication, marketing of the JKT48 fandom group in the context of the cultural Fandom, industry context. The culture industry can be interpreted as cultural culture industry, JKT48 production and consumption or contribution to cultural production. This reality is one of the popular culture products which is quite popular with a group of JKT 48 fans. This study uses a case study Kata Kunci: konstruksi pemasaran, method with interview and observation as data collection technique. Fandom, The results show that the social construction of fandom is formed on industri budaya, the same interest in a cultural form. The presence of JKT48 gives a new JKT48 color in forming a subculture about the concept of become a fan as a consumer of popular culture. This relates to the marketing of a culture as a form of cultural industry as a contribution in cultural production. SARI PATI Industri budaya secara khusus dapat diartikan menjadi produksi dan konsumsi barang dan jasa budaya atau kontribusi dalam produksi budaya. Sifat individu untuk menyukai dan menggemari musik, buku, film, seni rupa, olahraga dapat menjadi sasaran dari pengembangan industri budaya, penyuka, penggemar musik bahkan terkonstruksi menjadi konsumen. -

IR/19-00002 Aug 14, 2019 Subject: Submission of Financial

Management Discussion and Analysis for 2Q 2019 Ended 30 June2019 PB – IR/19-00002 Aug 14, 2019 Subject: Submission of Financial Statements and the Management Discussion and Analysis of Plan B Media Public Company Limited (“the Company”) for the three-month period ended June 30, 2019 (“2Q19”) To: The President The Stock Exchange of Thailand We are pleased to submit the following documents: 1. A copy of the Company Only and Consolidated Interim Financial Statements for the three-month period ended June 30, 2019 (a copy in Thai and English). 2. Management Discussion and Analysis (MD&A) for the three-month period ended June 30, 2019 (a copy in Thai and English). 3. The Company's performance report, Form F45-3 for the three-month period ended June 30, 2019 (a copy in Thai and English). Please be informed accordingly. Sincerely yours, (Pinijsorn Luechaikajohnpan, Ph.D.) Authorized Director Company Secretary Tel: +66 2 530-8053 Fax: +66 2 530-8053 Management Discussion and Analysis for 2Q 2019 Ended 30 June2019 1. Executive Summary 1.1 Financial Highlights for 2Q 2019 Total Revenue stood at THB 1,143.8 million, an increase of 30.4 % from the same period of the previous year. EBITDA was THB 393.7 million, a 29.3% jump from the same period of the previous year. Net Profit was recorded at THB 180.3 million, a surge of 18.2% from the same period of the previous year. Unit: THB Million 2Q 2018 2Q 2019 %Change (YoY) Total Revenue 877.4 1,143.8 30.4% EBITDA 304.4 393.7 29.3% Net Profit 152.6 180.3 18.2% 1.2 Summary of Other Important Details The Company posted total revenue of THB 1,143.8 million, equal to 30.4 % year-on-year growth thanks to the following factors o High revenue growth from out-of-home media was derived especially from digital out-of-home media and airport media that accelerated at a rate of 21.6% and 34.2% from the same period last year respectively resulting from the media development and variety enhancement during the past year. -

I STRATEGI JEPANG DALAM MENGEMBANGKAN INDUSTRI BUDAYA POPULER MELALUI AKB48 GROUP DI ASIA TENGGARA SKRIPSI Disusun Oleh

STRATEGI JEPANG DALAM MENGEMBANGKAN INDUSTRI BUDAYA POPULER MELALUI AKB48 GROUP DI ASIA TENGGARA SKRIPSI Disusun oleh: RATTANDI IBNU TSAQIF 20150510366 Pembimbing: Ratih Herningtyas, S.IP., M.A. PROGRAM STUDI HUBUNGAN INTERNASIONAL FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK UNIVERSITAS MUHAMMADIYAH YOGYAKARTA 2019 i HALAMAN PERSEMBAHAN Pertama-tama saya ucapkan rasa syukur atas kehadirat Allah SWT, karena dengan berkah, nikmat, dan hidayah-Nya, saya bisa menyelesaikan skripsi ini dengan lancar, baik, dan tepat waktu. Skripsi ini saya persembahkan kepada kedua orang tua saya, Teguh Rattan Nuson dan Ita Sapta Umalia, karena senantiasa mendukung saya saat berada dalam kegelisahan dalam penyusunan skripsi ini. Skripsi ini juga saya persembahkan kepada adik saya, Rattandi Ghulam Huwaidi dan Rattandi Ghaisan Hammadi. UCAPAN TERIMAKASIH Saya ucapkan terimakasih kepada kedua orang tua saya yang telah memberikan doa serta dukungannya selama proses pengerjaan skripsi ini. Tanpa doa kedua orang tua dan ridho Allah SWT, saya tidak akan bisa menyelesaikan skripsi ini. Saya juga mengucapkan terimakasih pada keluarga saya yang juga telah memberikan semangat serta doa untuk menyelesaikan tahap akhir studi S1 ini. Terima kasih juga kepada dosen pembimbing saya, ibu Ratih Herningtyas, S.IP., M.A. yang berkontribusi langsung serta memberikan arahan dalam menyusun skripsi ini. Tanpa beliau, saya hanyalah seorang penggemar jejepangan yang selalu berhalusinasi. Saya juga mengucapkan banyak terimakasih kepada seluruh dosen prodi HI UMY, khususnya yang pernah saya ambil mata kuliahnya. Akumulasi ilmu dan pengetahuan yang saya dapat dari Bapak dan Ibu juga lah saya bisa sampai di titik ini dan bisa menulis skripsi dengan baik dan lancar. Terimakasih juga untuk staf prodi HI UMY, khususnya Pak Jumari dan Pak Waluyo, yang sering saya ganggu. -

The Diffusion of Japanese Idol Concept Based on the Interpretation of Fan Clubs’ Behaviors

วารสารการประชาสัมพันธ์และการโฆษณา ปีที่ 12 ฉบับที่ 2 2562 …89 The Diffusion of Japanese Idol Concept Based on the Interpretation of Fan Clubs’ Behaviors Received: February 23, 2019 / Received in revised form: March 28, 2019 / Accepted: May 24, 2019 Peerawat Tan-intaraarj Thammasat University Abstract he concept of Japanese female idol groups is now being applied more widely outside T Japan. BNK48 is an idol group in Thailand that has applied this concept as a branch of the Japanese AKB48. At its start, it had a small number of fans; however, however they have risen since the release of their second single, “Koisuru Fortune Cookie”. Basically, the concept of Japanese female idol groups reflects a culture different from the Thai context. For this reason, this study was initiated to better understand how a Thai individual becomes a fan of BNK48 through observation. The research was conducted based on the phenomenological concept and observation generated through an individual’s experience. The four elements of Diffusion of Innovations Theory (innovation, time, communication channels and a social system) and Bandura’s Social Learning Theory were applied to clarify the findings collected through in- depth interviews and the observational research. For the in-depth interviews, all key informants who participated in this study admitted that they are BNK48 fans. The in-depth interview results show that social media and peers have an influence on key informants’ adoption. However, in the long term, the Thai context also has an effect on key informants. Although BNK48 applies the Japanese concept, key informants adopt this concept because they understand it easily, which is actually conveyed through a Thai context. -

BNK48 Makes Her Acting Debut in the Fantasy Thriller Homestay, It’S Easy to Assume She Got the Role Because of Her Fame

Bangkok Post Learning: Test Yourself Test Yourself is where you can improve your reading skills. Whether it’s for tests like University Entrance Exams or IELTS and TOEFL, or even just for fun, these pages help you to read, understand and improve your English. Here to stay by Gary Boyle. Photo by Chanut Katanyu Read the following story by Suwitcha Chaiyong from the Bangkok Post. Then, answer the questions that follow. When one of the most popular singers in the idol group BNK48 makes her acting debut in the fantasy thriller Homestay, it’s easy to assume she got the role because of her fame. But director Parkpoom Wongpoom chose Cherprang Areekul for Homestay in July of last year, long before BNK48 had its megahit single Koi Suru Fortune Cookie. UNDER PRESSURE With zero acting experience, the BNK48 captain beat other candidates because Parkpoom thought her looks matched the charming character, called Pie, who is the object of affection of a wandering spirit trapped in the body of Min (Teeradon “James” Supapunpinyo). “It is an honour to have the opportunity [to be in this big film], but it is also frustrating,” Cherprang said. “I wasn’t selected for my acting skill because I didn’t have any. I was under pressure to see how well I could do.” No young woman has had a more exciting year. Cherprang is the “captain” of BNK48, a Japan- style idol group in frilly costumes that commands the phenomenal devotion of fans. Cherprang, overseeing more than 20 younger girls, led her group to shake hands with Prime Minister Gen Prayut Chan-o-cha, and was later the subject of a mild scandal when she agreed to host an episode of the military government’s 6pm news show. -

39 Bab Iii Strategi Jepang Dalam Mengembangkan

BAB III STRATEGI JEPANG DALAM MENGEMBANGKAN INDUSTRI BUDAYA POPULER DI ASIA TENGGARA MELALUI AKB48 GROUP Budaya populer dapat memainkan peran dalam hubungan internasional Jepang. Budaya populer menjadi sarana untuk menjelaskan tentang budaya masyarakat Jepang kepada masyarakat internasional serta memberikan kesempatan untuk berkolaborasi dengan budaya lain. Maka dari itu, Jepang tidak akan melewatkan keuntungan besar yang dapat dihadirkan oleh budaya populer sehingga perlu adanya strategi khusus untuk dapat menjadikannya sebagai sarana penunjang perekonomian Jepang. Kawasan Asia Tenggara menjadi salah satu kawasan dengan peminat budaya populer yang tinggi, salah satu budaya populer yang diminati oleh masyarakat di kawasan ini adalah musik dari AKB48. A. Kebijakan Cool Japan Sebagai Strategi Jepang Sebagai Sarana Peningkatan Ekonomi Jepang telah menjadi kekuatan ekonomi yang dominan di Asia sejak transformasi selama Restorasi Meiji di akhir abad ke-19. Pada akhir 1980-an, Jepang memiliki GDP yang lebih besar dari gabungan seluruh kawasan (Fagoyinbo, 2013), dan dianggap sebagai kekuatan ekonomi Asia dengan industri manufaktur ekspornya yang kuat. Namun, ekonominya telah mengalami stagnasi sejak awal 1990-an, ketika pasar saham dan gelembung properti meledak. Situasi semakin memburuk mengingat tren internasional dan domestik baru-baru ini, seperti pasar global yang semakin kompetitif, kebangkitan Tiongkok dan populasi yang menua di dalam negeri. Jepang dulunya merupakan 17,9% dari ekonomi dunia pada tahun 1994, tetapi 39 40 bagiannya turun menjadi 8,8% pada akhir 2011 (Siddiqui, 2015). Pemerintah Jepang telah berjuang untuk menemukan strategi untuk memperbaiki ekonomi nasionalnya. Negara ini telah menerapkan sejumlah kebijakan fiskal dan moneter sejak awal 1990-an, tetapi negara ini masih terus berjuang untuk menarik diri dari stagnasi ekonomi. -

Download Overture Akb48

Download overture akb48 click here to download Watch the video, get the download or listen to AKB48 – overture for free. overture appears on the album チームA 5th Studio Recording「恋愛禁 止条例」. Discover more music, gig and concert tickets, videos, lyrics, free downloads and MP3s, and photos with the largest catalogue online at www.doorway.ru Home» AKB48» Overture» Download AKB48 - Overture. Download Overture AKB48 - Overture AKB48 - Overture adalah sebuah musik yang dipopulerkan oleh AKB Lagu ini berukuran KB yang bisa Anda download disini secara gratis sebagai review. Anda juga dapat merequest lagu yang. Title: overture. Artist: Team A; AKB Album: Team A 5th Stage: Renai Kinshi Jourei (??????) Studio Recordings. Duration: Size: KB. Audio Summary: Audio: mp3, Hz, stereo, s16p, kb/s. Added: Downloaded: +0/0x. Title: overture. Artist: Team K; AKB Album: Team K 6th Stage: RESET Studio Recordings Collection. Duration: Size: KB. Audio Summary: Audio: mp3, Hz, stereo, s16p, kb/s. Added: Downloaded: +0/0x. Title: overture. Artist: Team B; AKB Album: Team B 3rd Stage: Pajama Drive (????????) Studio Recordings Coll. Duration: Size: 1, KB. Audio Summary: Audio: mp3, Hz, stereo, s16p, kb/s. Added: Downloaded: +0/0x. Title: overture. Artist: Team K; AKB Album: Team K 4th Stage: Saishuu Bell ga naru (???????) Studio Recordin. Duration: Size: MB. Audio Summary: Audio: mp3, Hz, stereo, s16p, kb/s. Added: Downloaded: +0/0x. そんなこんなわけで (Sonna Konna Wake De) - AKB Publication date: AM 29/01/ | Listens: Play: Kbps Kbps Download: Kbps Kbps · Free to Play and Download Overture - AKB48 with hight quality mp3. [DAY 1] AKB48 in Tokyo Dome m (Disc 1 + Disc 2). -

Competencia Nacional De Cortometraje

04 PRESENTACIÓN 10 EQUIPO DE PROGRAMACIÓN 15 MEMORIA E IDENTIDAD 16 JURADOS 20 PREMIOS 22 PELÍCULA DE INAUGURACIÓN 24 COMPETENCIA CENTROAMERICANA DE LARGOMETRAJE 30 COMPETENCIA COSTARRICENSE DE LARGOMETRAJE 40 COMPETENCIA NACIONAL DE CORTOMETRAJE 52 PANORAMA 64 RADAR 76 FOCO 86 RETROSPECTIVA 94 CINE QUEER 100 ÚLTIMA TANDA 106 DE JÓVENES 112 CLÁSICOS DE CULTO 114 FORMACIÓN DISEÑO: CLAN PROCESAMIENTO DE CONTENIDOS: PLUGIN 116 INDUSTRIA 118 SEDES COSTA RICA 2019 120 CRÉDITOS 124 AGRADECIMIENTOS CRFIC 7 P 2 costaricacinefest.go.cr P 3 DE LA PUPA, LA No he querido reflexionar o El CRFIC a mí me ha Durante la sexta edición del Fue precisamente la ahondar acerca de determinados transformado cual plasticina CRFIC, el artista costarricense contemplación de esta pupa cambios, sino permanecer en moldeada por hábiles manos; Jonathan Torres logró crear una de mariposa suspendida la las transformaciones, porque plasticina que puede ser estatuilla para premios que es que nos inspiró a comenzar a diferencia del cambio (que un corazón, un cuerno de estéticamente delicada y etérea, a diseñar la séptima edición significa extraer algo para la abundancia o una masa pero que a su vez incorpora del festival, con las energías poner otra cosa en su lugar), la abstracta y colorida, todo una valoración poderosa: la encauzadas hacia la búsqueda PLASTICINA transformaciónY implicaLA asumir al mismo tiempo. Nuestro propuesta, a nivel formal, parte de esa misma transparencia: lo que tenemos para a partir empeño es que varias de las de la geometría de una pupa permitir y permitirnos observar de ahí proponer ideas distintas, historias cinematográficas que de mariposa en gestación, y en el proceso de maduración al que intentando rescatar lo perdurable compartimos hoy también su interior puede observarse estamos abocados; maduración y replantear lo modificable. -

BNK 48 a Thai-Japanese Cultural Commodity in the Stagnation of Thai Music Business: Contemporary Entertainment Business History

Journal of Advanced Research in Social Sciences and Humanities Volume 3, Issue 4 (136-141) DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.26500/JARSSH-03-2018-0402 BNK 48 a Thai-Japanese cultural commodity in the stagnation of Thai music business: Contemporary entertainment business history DOME KRAIPAKORN ∗ Srinakarinwirot University, Bangkok, Thailand Abstract Aim: This article explores the success of the BNK48 music group in Thailand, which has risen significantly from the end of 2017 to the present (early 2018), considering the fact that the overall environment of Thailand’s music industry has been quite slow. Method: The study uses a historical perspective to study the formation of BNK48’s popularity from interviews with the singers and company executives published in magazines and pocketbooks. Findings: The consumption of cultural commodity is when a consumer purchase a product to consume the product’s value or meaning, not only using such a product. If we see BNK48 as a "cultural commodity," which is interpreted from the perspective that "otakus" purchase BNK48 products to consume values or meaning to see the success of the idols who are interested in cartoons, games, and cosplay, similar to themselves, as well as the self-improvement efforts of the idols which is the value attached to the stories and are consistent with the cultures and feelings of young people in the late 2000s. Implications/Novel Contribution: Present research leads to literature through a thorough understanding of BNK’s cultural and emotional connections with its followers. Keywords: