Art of Queering Asian Mythology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adaptive Fuzzy Pid Controller's Application in Constant Pressure Water Supply System

2010 2nd International Conference on Information Science and Engineering (ICISE 2010) Hangzhou, China 4-6 December 2010 Pages 1-774 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1076H-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-7616-9 1 / 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS ADAPTIVE FUZZY PID CONTROLLER'S APPLICATION IN CONSTANT PRESSURE WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM..............................................................................................................................................................................................................1 Xiao Zhi-Huai, Cao Yu ZengBing APPLICATION OF OPC INTERFACE TECHNOLOGY IN SHEARER REMOTE MONITORING SYSTEM ...............................5 Ke Niu, Zhongbin Wang, Jun Liu, Wenchuan Zhu PASSIVITY-BASED CONTROL STRATEGIES OF DOUBLY FED INDUCTION WIND POWER GENERATOR SYSTEMS.................................................................................................................................................................................9 Qian Ping, Xu Bing EXECUTIVE CONTROL OF MULTI-CHANNEL OPERATION IN SEISMIC DATA PROCESSING SYSTEM..........................14 Li Tao, Hu Guangmin, Zhao Taiyin, Li Lei URBAN VEGETATION COVERAGE INFORMATION EXTRACTION BASED ON IMPROVED LINEAR SPECTRAL MIXTURE MODE.....................................................................................................................................................................18 GUO Zhi-qiang, PENG Dao-li, WU Jian, GUO Zhi-qiang ECOLOGICAL RISKS ASSESSMENTS OF HEAVY METAL CONTAMINATIONS IN THE YANCHENG RED-CROWN CRANE NATIONAL NATURE RESERVE BY SUPPORT -

History of Badminton

Facts and Records History of Badminton In 1873, the Duke of Beaufort held a lawn party at his country house in the village of Badminton, Gloucestershire. A game of Poona was played on that day and became popular among British society’s elite. The new party sport became known as “the Badminton game”. In 1877, the Bath Badminton Club was formed and developed the first official set of rules. The Badminton Association was formed at a meeting in Southsea on 13th September 1893. It was the first National Association in the world and framed the rules for the Association and for the game. The popularity of the sport increased rapidly with 300 clubs being introduced by the 1920’s. Rising to 9,000 shortly after World War Π. The International Badminton Federation (IBF) was formed in 1934 with nine founding members: England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Denmark, Holland, Canada, New Zealand and France and as a consequence the Badminton Association became the Badminton Association of England. From nine founding members, the IBF, now called the Badminton World Federation (BWF), has over 160 member countries. The future of Badminton looks bright. Badminton was officially granted Olympic status in the 1992 Barcelona Games. Indonesia was the dominant force in that first Olympic tournament, winning two golds, a silver and a bronze; the country’s first Olympic medals in its history. More than 1.1 billion people watched the 1992 Olympic Badminton competition on television. Eight years later, and more than a century after introducing Badminton to the world, Britain claimed their first medal in the Olympics when Simon Archer and Jo Goode achieved Mixed Doubles Bronze in Sydney. -

Women's Doubles Results Gold Silver Bronze Bronze World Championships Yang Wei / Zhang Jiewen Gao Ling / Huang Sui Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen Kumiko Ogura / Reiko Shiota

⇧ 2008 Back to Badzine Results Page 2007 Women's Doubles Results Gold Silver Bronze Bronze World Championships Yang Wei / Zhang Jiewen Gao Ling / Huang Sui Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen Kumiko Ogura / Reiko Shiota Super Series Malaysia Open Gao Ling / Huang Sui Vita Marissa / Gresya Polii Hwang Yu Mi / Kim Min Jung Kumiko Ogura / Reiko Shiota Korea Open Gao Ling / Huang Sui Yang Wei / Zhang Jiewen Lee Hyo Jung / Lee Kyung Won Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen All England Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen Yang Wei / Zhang Jiewen Gao Ling / Huang Sui Chin Eei Hui / Wong Pei Tty Swiss Open Yang Wei / Zhao Tingting Lee Hyo Jung / Lee Kyung Won Cheng Wen Hsing / Chien Yu Chin Vita Marissa / Gresya Polii Singapore Open Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen Yang Wei / Zhao Tingting Lee Hyo Jung / Lee Kyung Won Gao Ling / Zhang Jiewen Indonesia Open Du Jing / Yu Yang Yang Wei / Zhao Tingting Gao Ling / Zhang Jiewen Gail Emms / Donna Kellogg China Masters Vita Marissa / Liliyana Natsir Yang Wei / Zhao Tingting Du Jing / Yu Yang Gail Emms / Donna Kellogg Japan Open Yang Wei / Zhang Jiewen Yu Yang / Zhao Tingting Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen Gao Ling / Huang Sui Denmark Open Yang Wei / Zhang Jiewen Lee Hyo Jung / Lee Kyung Won Yu Yang / Zhao Tingting Gail Emms / Donna Kellogg French Open Yang Wei / Zhang Jiewen Yu Yang / Zhao Tingting Cheng Wen Hsing / Chien Yu Chin Jo Novita / Gresya Polii China Open Gao Ling / Zhao Tingting Du Jing / Yu Yang Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen Pan Pan / Tian Qing Hong Kong Open Du Jing / Yu Yang Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen Cheng Wen Hsing / Chien Yu Chin Gao Ling / Zhao Tingting -

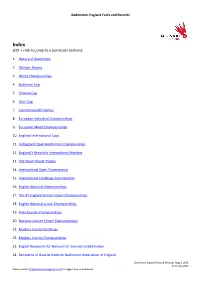

Facts and Records

Badminton England Facts and Records Index (cltr + click to jump to a particular section): 1. History of Badminton 2. Olympic Games 3. World Championships 4. Sudirman Cup 5. Thomas Cup 6. Uber Cup 7. Commonwealth Games 8. European Individual Championships 9. European Mixed Championships 10. England International Caps 11. All England Open Badminton Championships 12. England’s Record in International Matches 13. The Stuart Wyatt Trophy 14. International Open Tournaments 15. International Challenge Tournaments 16. English National Championships 17. The All England Seniors’ Open Championships 18. English National Junior Championships 19. Inter-County Championships 20. National Leisure Centre Championships 21. Masters County Challenge 22. Masters County Championships 23. English Recipients for Honours for Services to Badminton 24. Recipients of Awards made by Badminton Association of England Badminton England Facts & Records: Page 1 of 86 As at May 2021 Please contact [email protected] to suggest any amendments. Badminton England Facts and Records 25. English recipients of Awards made by the Badminton World Federation 1. The History of Badminton: Badminton House and Estate lies in the heart of the Gloucestershire countryside and is the private home of the 12th Duke and Duchess of Beaufort and the Somerset family. The House is not normally open to the general public, it dates from the 17th century and is set in a beautiful deer park which hosts the world-famous Badminton Horse Trials. The Great Hall at Badminton House is famous for an incident on a rainy day in 1863 when the game of badminton was said to have been invented by friends of the 8th Duke of Beaufort. -

Svetska Prvenstva

SVJETSKA PRVENSTVA (1977-2010 ) Malmo– 1977 M - Flemming Delfs (DEN) Ž - Lene Koppen (DEN) MM - Tjun Tjun/Johan Wahjudi (INA) ŽŽ - Etsuko Toganoo/Erniko Ueno (JPN) MŽ - Steen Skovgaard/Lene Koppen (DEN) Jakarta– 1980 M - Rudy Hartono (INA) Ž - Verawaty Wiharjo (INA) MM - Ade Chandra/Christian Hadinata (INA) ŽŽ - Nora Perry/Jane Webster (ENG) MŽ - Christian Hadinata/Imelda Wiguno (INA) Kopenhagen– 1983 M - Icuk Sugiarto (INA) Ž - Li Lingwei (CHN) MM - Steen Fladberg/Jesper Helledie (DEN) ŽŽ - Lin Ying/Wu Dixi (CHN) MŽ - Thomas Kihlstrom/Nora Perry (SWE/ENG) Calgary– 1985 M - Han Jian (CHN) Ž - Han Aiping (CHN) MM - Park Joo Bong/Kim Moon Soo (KOR) ŽŽ - Han Aiping/Li Lingwei (CHN) MŽ - Park Joo Bong/Yoo Sang Hee (KOR) Peking– 1987 M - Yang Yang (CHN) Ž - Han Aiping (CHN) MM - Li Yongbo/Tian Bingyi (CHN) ŽŽ - Lin Ying/Guan Weizhen (CHN) MŽ - Wang Pengren/Shi Fangjing (CHN) Jakarta– 1989 M - Yang Yang (CHN) Ž - Li Lingwei (CHN) MM - Li Yongbo/Tian Bingyi (CHN) ŽŽ - Lin Ying/Guan Weizhen (CHN) MŽ - Park Joo Bong/Chung Myung Hee (KOR) Kopenhagen– 1991 M - Zhao Jianhua (CHN) Ž - Tang Jiuhong (CHN) MM - Park Joo Bong/Kim Moon Soo (KOR) ŽŽ - Guan Weizhen/Nong Qunhua (CHN) MŽ - Park Joo Bong/Chung Myung Hee (KOR) Birmingam– 1993 M - Joko Suprianto (INA) Ž - Susi Susanti (INA) MM - Ricky Subagja/Rudy Gunawan (INA) ŽŽ - Nong Qunhua/Zhou Lei (CHN) MŽ - Thomas Lund/Catrine Bengtsson (DEN/SWE) Lausanne– 1995 M - Heryanto Arbi (INA) Ž - Ye Zhaoying (CHN) MM - Rexy Mainaky/Ricky Subagja (INA) ŽŽ - Gil Young Ah/Jang Hye Ock (KOR) MŽ - Thomas Lund/Marlene -

Olimpijske Igre (1992-2008)

OLIMPIJSKE IGRE (1992-2008) Barcelona, 1992 Men’s Singles 1. Allan Budi Kusuma (INA) 2. Ardy Bernardus Wiranata (INA) 3. Thomas Stuer-Lauridsen (DEN) Hermawan Susanto (INA) Ladies’ Singles 1. Susi Susanti (INA) 2. Bang Soo-Hyun (KOR) 3. Huang Hua (CHN) Tang Jiuhong (CHN) Men’s Doubles 1. Park Joo-Bong / Kim Moon-Soo (KOR) 2. Eddy Hartono / Rudy Gunawan (INA) 3. Rashid Sidek / Razif Sidek (MAS) Li Yongbo / Tian Bingyi (CHN) Ladies’ Doubles 1. Hwang Hae-Young / Chung So-Young (KOR) 2. Guan Weizhen / Nong Qunhua (CHN) 3. Gil Young-Ah / Shim Eun-Jung (KOR) Lin Yanfen / Yao Fen (CHN) Atlanta, 1996 Men’s Singles 1. Poul Erik Hoyer-Larsen (DEN) 2. Dong Jiong (CHN) 3. Rashid Sidek (MAS) Ladies’ Singles 1. Bang Soo-Hyun (KOR) 2. Mia Audina (INA) 3. Susi Susanti (INA) Men’s Doubles 1. Ricky Achmad Subagja / Rexy Ronald Mainaky (INA) 2. Cheah Soon Kit / Yap Kim Hock (MAS) 3. Denny Kantono / Irianto Antonius (INA) Ladies’ Doubles 1. Ge Fei / Gu Jun (CHN) 2. Gil Young-Ah / Jang Hye Ock (KOR) 3. Qin Yiyuan / Tang Yongshu (CHN) Mixed Doubles 1. Zhang Jun / Gao Ling (CHN) 2. Park Joo-Bong / Ra Kyung-Min (KOR) 3. Liu Jianjun / Sun Man (CHN) Sydney, 2000 Men’s Singles 1. Ji Xinpeng (CHN) 2. Hendrawan (INA) 3. Xia Xuanze (CHN) Ladies’ Singles 1. Gong Zhichao (CHN) 2. Camilla Martin (DEN) 3. Ye Zhaoying (CHN) Men’s Doubles 1. Tony Gunawan / Candra Wijaya (INA) 2. Lee Dong Soo / Yoo Yong-Sung (KOR) 3. Ha Tae-Kwon / Kim Dong Moon (KOR) Ladies’ Doubles 1. -

Badminton World Federation Bwf Handbook Ii

HANDBOOK I I LAWS OF BADMINTON | REGULATIONS BADMINTON WORLD FEDERATION BWF HANDBOOK II (Laws of Badminton & Regulations) 2010/2011 It is the duty of everyone concerned with badminton to keep themselves informed about the BWF Statutes COPYRIGHT ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Permission to reprint material in this book, either wholly or in part in any form whatsoever, must be obtained from the Badminton World Federation Updated 25 May 2010 by BADMINTON WORLD FEDERATION Stadium Badminton Kuala Lumpur Batu 3 ½ , Jalan Cheras 56000 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Tel: +603-9283 7155 / 6155 / 2155 Fax: +603-9284 7155 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: www.bwfbadminton.org CONTENTS 2 Laws of Badminton ....................................................................................................... 4 Laws of Badminton (Appendix 1-6) ............................................................................ 14 Recommendation to Technical Officials ..................................................................... 30 General Competition Regulations ............................................................................... 41 Appendix 1 - International Representation Chart ..................................................... 80 Appendix 2 - Specifications for International Standard Facilities ........................... 81 Appendix 3 – Anti Doping Regulations ....................................................................... 83 Appendix 4 – Players’ Code of Conduct ..................................................................... 120 Appendix -

The Interpretation of Chinese Traditional Culture by Lin Dan

2nd International Conference on Economics, Social Science, Arts, Education and Management Engineering (ESSAEME 2016) The Interpretation of Chinese Traditional Culture by Lin Dan badminton Aesthetics Yang Lu1, a 1Department of Physical Education, Wuhan Polytechnic, Wuhan, China [email protected] Keywords: Lin Dan; badminton; aesthetics; Chinese traditional culture; style. Abstract. Lin Dan's badminton is full of art, he will be turned into a more in line with the badminton movement Chinese understanding. Through literature, the Internet in the analysis of Lin Dan's reports and case found that Lin Dan's style of traditional culture Chinese badminton permeated with the shadow, the transmission of traditional culture China flash point: in the western financial learn widely from others'strong points, Lin Dan speed assault another revolution to promote play badminton; the sun Tzu Chi and the badminton, to learn to play with my mind, to change the status quo; a statue of Shang Tianren Ren Chong, advocating noble character and great boldness; unremitting self-improvement social commitment decided the outcome of the game, the key is the inner sword of Mo Liying; male hardships experienced failures and frustrations withstood pressure from all sides to make a difference. Why is this China audience obsessed with Lin Dan. Introduction Lindan in Olympic Games, world championships, world cup, the Thomas Cup, Sudirman Cup, Britain race, FIBA Asia Championships, Asian Games champion in the "super grand slam", he created a belongs to own time, created the badminton a may never copied myth. At present, a total of 19 world champions, into the history of the first person. -

Women's Doubles Results Gold Silver Bronze Bronze Beijing Olympic Games Du Jing / Yu Yang Lee Hyo Jung / Lee Kyung Won Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen

⇧ 2009 Back to Badzine Results Page ⇩ 2007 2008 Women's Doubles Results Gold Silver Bronze Bronze Beijing Olympic Games Du Jing / Yu Yang Lee Hyo Jung / Lee Kyung Won Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen Super Series Malaysia Open Yang Wei / Zhang Jiewen Gao Ling / Zhao Tingting Du Jing / Yu Yang Lee Hyo Jung / Lee Kyung Won Korea Open Du Jing / Yu Yang Gao Ling / Zhao Tingting Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen Lee Hyo Jung / Lee Kyung Won All England Lee Hyo Jung / Lee Kyung Won Du Jing / Yu Yang Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen Yang Wei / Zhang Jiewen Swiss Open Yang Wei / Zhang Jiewen Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen Lee Hyo Jung / Lee Kyung Won Du Jing / Yu Yang Singapore Open Du Jing / Yu Yang Cheng Wen Hsing / Chien Yu Chin Ha Jung Eun / Kim Min Jung Vita Marissa / Liliyana Natsir Indonesia Open Vita Marissa / Liliyana Natsir Miyuki Maeda / Satoko Suetsuna Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen Shendy Puspa Irawati / Meiliana Jauhari Japan Open Cheng Shu / Zhao Yunlei Chin Eei Heui / Wong Pei Tty Miyuki Maeda / Satoko Suetsuna Vita Marissa / Liliyana Natsir China Masters Cheng Shu / Zhao Yunlei Zhang Dan / Zhang Zhibo Duang Anong Aroonkesorn / Kunchala Voravichitchaikul Nicole Grether / Charmaine Reid Denmark Open Chin Eei Heui / Wong Pei Tty Rani Mundiasti / Jo Novita Nitya Krishinda Maheswari / Gresya Polii Judith Meulendijks / Yao Jie French Open Du Jing / Yu Yang Chin Eei Heui / Wong Pei Tty Cheng Shu / Zhao Yunlei Zhang Yawen / Zhao Tingting China Open Zhang Yawen / Zhao Tingting Chin Eei Heui / Wong Pei Tty Du Jing / Yu Yang Ha Jung Eun / Kim Min Jung Hong Kong Open Zhang Yawen / Zhao -

Selected Results of World Badminton Championships 08:17, August 16, 2007

Selected results of world badminton championships 08:17, August 16, 2007 Following are the selected results of the 16th world badminton championships on Wednesday: Men's singles: Park Sung Hwan, South Korea, bt Andrew Dabeka, Canada, 21-16, 21-5 Kenneth Jonassen, Denmark, bt Nicholas Kidd, England, 21-14, 21-7 Chen Yu, China, bt Bjoern Joppien, Germany, 21-15, 21-7 Ronald Susilo, Singapore, bt Richard Vaughan, Wales, 21-17, 21-17 Anup Sridhar, India, bt Taufik Hidayat, Indonesia, 21-14, 24-26, 22-20 Peter Gade, Denmark, bt Chan Yan Kit, Hong Kong, China, 21-18, 25-23 Muhd Hafiz B Hashim, Malaysia, bt Scott Evans, Ireland, 21-19, 14-21, 21-11 Lee Chong Wei, Malaysia, bt Eric Pang, Netherlands, 21-7, 21-11 Lin Dan, China, bt Wei Ng, Hong Kong, China, 21-8, 21-10 Bao Chunlai, China, bt Lee Tsuen Seng, Malaysia, 21-14, 18-21, 21-18 Women's singles: Pi Hongyan, France, bt Charmaine Reid, Canada, 21-13, 21-12 Wang Chen, Hong Kong, China, bt Li Li, Singapore, 21-13, 21-6 Zhang Ning, China, bt Jang Soo Young, South Korea, 21-9, 21-14 Tracey Hallam, England, bt Kamila Augustyn, Poland, 15-21, 21-16, 21-11 Wong Mew Choo, Malaysia, bt Ekaterina Ananina, Russia, 21-14, 22-20 Xie Xingfang, China, bt Ana Moura, Portugal, 21-2, 21-7 Ella Karachkova, Russia, bt Yao Jie, Netherlands, 22-20, 14-21, 21-17 Zhu Lin, China, bt Anna Rice, Canada, 21-18, 21-13 Maria Kristin Yulianti, Indonesia, bt Wong Pei Xian Julia, Malaysia, 16-21, 21-14, 21-18 Lu Lan, China, bt Judith Meulendijks, Netherlands, 21-18, 21-13 Men's doubles: Choong Tan Fook/Lee Wan Wah, Malaysia, -

Badmintonmuseet

Midt i den lidt nedslående danske VM-status - den enli ge bronzemedalje til Jane Jacoby/Britta Andersen - var der trods alt også grund til glæde over en en massiv dansk repræsentation i kvart finalerne i doublerækkeme. Aldrig før har en sådan bred de af danske spillere været så langt fremme. Tre mixeddoubler frem til kvartfinaler - med tre neder lag til følge - og to kvartfina lepladser i herredouble, lige ledes med nederlag som resultat. Hertil kommer altså kvartfi- nalepladsen i damedouble til Britta Andersen/Jane Jacoby, der også kom ud over denne forhindring. For Kasper Ødum og Ove Svejstrup er nederlaget til Gan/Chan, Malaysia, særligt bittert - set i bakspejlet. Først og fremmest den kedelige kendsgerning, at Randers- Jane Jacoby og Britta Andersen spiller parret faktisk havde sejren sig igennem til sem ifinalen - og det giver godt og grundigt inden fof forhåbninger for Ove Svejstrup, M ichael rækkevidde med føring på Kjeldsen og Kasper Ødum. M en nej. 11-4 i tredje sæt. For det andet spillede atsaterne sig siden frem til VM-titlen. Det har været en forrygende sæson for Thomas Røjkjæf og Tommy Sørensen, der spillede sig ind i VM-trup- MIXED- pen i løbet af efteråret med en række flotte præstationer. De stod for en VM-indsats ud over forventningerne. DOUBLER Det gælder først og frem mest deres sejr i ottendedels finalen over Noor/Edwin, Indonesien. De vendte 3-15 i TÆ T PÅ første sæt til sejr på 15-3, 15- 6 i de to næste. TRE DANSKE PAR NÅEDE TIL De kunne dog ikke gentage KVARFINALERNE bedriften i kvartfinalen mod Yim Bang Eun/Kim Yong. -

Womens Doubles All England 1899 to 2009

WOMENS DOUBLES 1899 to 2009 1899 - Muriel Lucas - later Adams/Graeme (England) 1900 - Muriel Lucas - later Adams/Graeme (England) 1901 - Daisey St.John/E. Moseley - later Allen (England) 1902 - Ethel W. Thomson - later Larcombe/Muriel Lucas - later Adams (England) 1903 - M. Hardy/Dorothea K. Douglas - later Lambert Chambers (England) 1904 - Ethel W. Thomson - later Larcombe/Muriel Lucas - later Adams (England) 1905 - Ethel W. Thomson - later Larcombe/Muriel Lucas - later Adams (England) 1906 - Ethel W. Thomson - later Larcombe/Muriel Lucas - later Adams (England) 1907 - G.L. Murray/Muriel Lucas - later Adams (England) 1908 - G.L. Murray/Muriel Lucas - later Adams (England) 1909 - G.L. Murray/Muriel Lucas - later Adams (England) 1910 - M.K. Bateman - later Flaxman/Muriel Lucas - later Adams (England) 1911 - A. Gowenlock/D. Cundall - later Bisgood (England) 1912 - A. Gowenlock/D. Cundall - later Bisgood (England) 1913 - Hazel Hogarth/M.K. Bateman - later Flaxman (England) 1914 - Margaret Rivers Tragett - formerly Larminie/Eveline Grace Peterson (England) 1915-1919 - Cancelled during World War I 1920 - Lavinia C. Radeglia/Violet Elton (England) 1921 - Kathleen 'Kitty' McKane - later Godfree/Margaret McKane - later Stocks (England) 1922 - Margaret Rivers Tragett - formerly Larminie/Hazel Hogarth (England) 1923 - Margaret Rivers Tragett - formerly Larminie/Hazel Hogarth (England) 1924 - Margaret Stocks - formerly McKane/Kathleen 'Kitty' McKane - later Godfrey (England) 1925 - Margaret Rivers Tragett - formerly Larminie/Hazel Hogarth (England)