A Comparison of the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonics During the Third Reich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SWR2 Musikstunde

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT ESSAYS FEATURES KOMMENTARE VORTRÄGE SWR2 Musikstunde „Dirigierende Komponisten und komponierende Dirigenten“ (5) Von Thomas Rübenacker Sendung: Freitag, 15. Juli 2016 9.05 – 10.00 Uhr Redaktion: Bettina Winkler Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Mitschnitte auf CD von allen Sendungen der Redaktion SWR2 Musik sind beim SWR Mitschnittdienst in Baden-Baden für € 12,50 erhältlich. Bestellungen über Telefon: 07221/929-26030 Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2-Kulturpartner-Netz informiert.Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2 2 „Musikstunde“ mit Thomas Rübenacker „Dirigierende Komponisten und komponierende Dirigenten“ (5) Von Thomas Rübenacker SWR 2, 11. Juli – 15. Juli 2016, 9h05 – 10h00 Signet: SWR2 Musikstunde … mit Thomas Rübenacker. Heute: „Komponierende Dirigenten und dirigierende Komponisten“, Teil 5. MUSIK Diese Woche sprach ich über komponierende Dirigenten und dirigierende Komponisten, also auch über das Verhältnis zwischen Schöpfer und Interpret in einer Person. Heute, in der letzten Sendung zum Thema, will ich mich auf „komponierende Kapellmeister“ kaprizieren, weil es da noch so einiges aufzuarbeiten gibt – vieles wenig bis gar nicht Bekanntes, auch manch Skurriles oder gar Schräges. Wie ich bereits sagte, griffen die Komponisten häufig zum baton, um ihre Werke zu schützen – und um mit der Welt konfrontiert zu werden, nicht nur mit dem häuslichen Schreibtisch. -

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

Texte Und Rezension Furtwängler Box Engl.Indd

MUSIKPRODUKTION Press Info: Wilhelm Furtwängler Berlin Philharmonic MASTERst RELEASE THE COMPLETE ORIGINAL TAPES RIAS RECORDINGS 1 Live in Berlin (1947 - 1954) 12 CD-Box + Bonus-CD The majority of the concerts given by Wilhelm Furtwängler and the Berlin Philharmonic between 1947 and 1954 were recorded by the RIAS Berlin; all of these recordings are documented in this boxed set. The original tapes from the RIAS archives have been made available for the first time for this edition so these CDs also offer unsurpassed technical quality. Furthermore, some of the recordings are presented for the very first time, such as the Fortner Violin Concerto with Gerhard Taschner. These RIAS recordings are documents of historical value: they contain a major part of Furtwängler’s late oeuvre as a conductor, which was characterised by a high level of focus in different respects. Focus on repertoire which has at its core the symphonic works of Beethoven, Brahms and Bruckner and is supplemented by works by Bach and Handel and also by topical composers of the time, including Hindemith, Blacher and Fortner: artists who were counted amongst the members of “moderate modernism” and who were not perceived to have been tainted by the cultural politics of the National Socialists. Focus was also a guiding principle in Furtwängler’s concert programmes which always feature a particular idea. His interpretations also demonstrate extremely high levels of focus: concentration and focus for him meant a contem- porary decoding, a re-creation, which would express the fundamental content of a work. A number of works – the Third, Fifth and Sixth Symphonies by Ludwig van Beethoven as well as Johannes Brahms’ Third Symphony – are included in two interpretations. -

Rezension Für: Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin

Rezension für: Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin Edition Friedrich Gulda – The early RIAS recordings Ludwig van Beethoven | Claude Debussy | Maurice Ravel | Frédéric Chopin | Sergei Prokofiev | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 4CD aud 21.404 Radio Stephansdom CD des Tages, 04.09.2009 ( - 2009.09.04) Aufnahmen, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Glasklar, "gespitzter Ton" und... Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Neue Musikzeitung 9/2009 (Andreas Kolb - 2009.09.01) Konzertprogramm im Wandel Konzertprogramm im Wandel Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Piano News September/Oktober 2009, 5/2009 (Carsten Dürer - 2009.09.01) Friedrich Guldas frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen Friedrich Guldas frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. page 1 / 388 »audite« Ludger Böckenhoff • Tel.: +49 (0)5231-870320 • Fax: +49 (0)5231-870321 • [email protected] • www.audite.de DeutschlandRadio Kultur - Radiofeuilleton CD der Woche, 14.09.2009 (Wilfried Bestehorn, Oliver Schwesig - 2009.09.14) In einem Gemeinschaftsprojekt zwischen dem Label "audite" und Deutschlandradio Kultur werden seit Jahren einmalige Aufnahmen aus den RIAS-Archiven auf CD herausgebracht. Inzwischen sind bereits 40 CD's erschienen mit Aufnahmen von Furtwängler und Fricsay, von Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau u. v. a. Die jüngste Produktion dieser Reihe "The Early RIAS-Recordings" enthält bisher unveröffentlichte Aufnahmen von Friedrich Gulda, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Die Einspielungen von Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel und Chopin zeigen den jungen Pianisten an der Schwelle zu internationalem Ruhm. Die Meinung unserer Musikkritiker: Eine repräsentative Auswahl bisher unveröffentlichter Aufnahmen, die aber bereits alle Namen enthält, die für Guldas späteres Repertoire bedeutend werden sollten: Mozart, Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel, Chopin. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

Clarinet Concertos Nos. 1 and 2

WEBER Clarinet Concertos Nos. 1 and 2 Concertina Ernst Ottensamer, Clarinet Czecho-Slovak State Philharmonic (Kdce) Johannes Wildner Carl Maria von Weber (1786 - 1826) Clarinet Concerto No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 73 (J. 109) Clarinet Concerto No. 2 in E Flat Major, Op. 74 (J. 114) Clarinet Concertino in E Flat Major, Op. 26 (J. 118) It was natural that there should be an element of the operatic in the music of Weber. The composer of the fint great Romantic German opera, Der Freischutz, spent much of his childhood with the peripatetic theatre company directed by his father, Franz Anton Weber, uncle of Mozart's wife Constanze and, like his brother, Constanze's Father, at one time a member of the famous Mannheim orchestra. At the time of Weber's birth his father was still in the service of the Bishop of Lubeck and during the course of an extended visit to Vienna had taken a second wife, an actress and singer, who became an important member of the family theatre company established in 1788. Weber's musical gifts were fostered by his father, who saw in his youngest son the possibility of a second Mozart. Travel brought the chance of varied if inconsistent study, in Salzburg with Michael Haydn and elsewhere with musicians of lesser ability. His second opera was performed in Freiberg in 1800, followed by a third in Augsburg in 1803. Lessons with the Abbe Vogler led to a position as Kapellmeister in Breslau in 1804, brought to a premature end through the hostility of musicians long established in the city and through the accidental drinking of engraving acid, left by his father in a wine-bottle. -

Berliner Philharmoniker

Berliner Philharmoniker Sir Simon Rattle Artistic Director November 12–13, 2016 Hill Auditorium Ann Arbor CONTENT Concert I Saturday, November 12, 8:00 pm 3 Concert II Sunday, November 13, 4:00 pm 15 Artists 31 Berliner Philharmoniker Concert I Sir Simon Rattle Artistic Director Saturday Evening, November 12, 2016 at 8:00 Hill Auditorium Ann Arbor 14th Performance of the 138th Annual Season 138th Annual Choral Union Series This evening’s presenting sponsor is the Eugene and Emily Grant Family Foundation. This evening’s supporting sponsor is the Michigan Economic Development Corporation. This evening’s performance is funded in part by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and by the Michigan Council for Arts and Cultural Affairs. Media partnership provided by WGTE 91.3 FM and WRCJ 90.9 FM. The Steinway piano used in this evening’s performance is made possible by William and Mary Palmer. Special thanks to Tom Thompson of Tom Thompson Flowers, Ann Arbor, for his generous contribution of lobby floral art for this evening’s performance. Special thanks to Bill Lutes for speaking at this evening’s Prelude Dinner. Special thanks to Journeys International, sponsor of this evening’s Prelude Dinner. Special thanks to Aaron Dworkin, Melody Racine, Emily Avers, Paul Feeny, Jeffrey Lyman, Danielle Belen, Kenneth Kiesler, Nancy Ambrose King, Richard Aaron, and the U-M School of Music, Theatre & Dance for their support and participation in events surrounding this weekend’s performances. Deutsche Bank is proud to support the Berliner Philharmoniker. Please visit the Digital Concert Hall of the Berliner Philharmoniker at www.digitalconcerthall.com. -

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years)

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years) 8 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe; first regular (not guest) performance with Vienna Opera Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Miller, Max; Gallos, Kilian; Reichmann (or Hugo Reichenberger??), cond., Vienna Opera 18 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Gallos, Kilian; Betetto, Hermit; Marian, Samiel; Reichwein, cond., Vienna Opera 25 Aug 1916 Die Meistersinger; LL, Eva Weidemann, Sachs; Moest, Pogner; Handtner, Beckmesser; Duhan, Kothner; Miller, Walther; Maikl, David; Kittel, Magdalena; Schalk, cond., Vienna Opera 28 Aug 1916 Der Evangelimann; LL, Martha Stehmann, Friedrich; Paalen, Magdalena; Hofbauer, Johannes; Erik Schmedes, Mathias; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 30 Aug 1916?? Tannhäuser: LL Elisabeth Schmedes, Tannhäuser; Hans Duhan, Wolfram; ??? cond. Vienna Opera 11 Sep 1916 Tales of Hoffmann; LL, Antonia/Giulietta Hessl, Olympia; Kittel, Niklaus; Hochheim, Hoffmann; Breuer, Cochenille et al; Fischer, Coppelius et al; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 16 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla Gutheil-Schoder, Carmen; Miller, Don José; Duhan, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 23 Sep 1916 Die Jüdin; LL, Recha Lindner, Sigismund; Maikl, Leopold; Elizza, Eudora; Zec, Cardinal Brogni; Miller, Eleazar; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 26 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla ???, Carmen; Piccaver, Don José; Fischer, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 4 Oct 1916 Strauss: Ariadne auf Naxos; Premiere -

Bernadette Mayrhofer Hugo Burghauser (Bassoon I, Chairman) Born 27 February 1896, Vienna, Died 9 December 1982, New York

Bernadette Mayrhofer Hugo Burghauser (Bassoon I, Chairman) born 27 February 1896, Vienna, died 9 December 1982, New York Joined the Staatsoper and the orchestra of the Vienna Philharmonic 1 November 1919 Resigned from the orchestra by leaving Austria illegally on 12 September 1938 Dismissal from the Academy of Music on 31 August 1938, resignation from the Vienna Philharmonic and Staatsoper on 31 August 1939 Training/Teachers: 1913 – 1919 Academy of Music, final exam bassoon on 26 June 1919. His most notable teachers were Johann Böhm (bassoon) and Dr. Joseph Marx (counterpoint); Additional professional activities: member of the Wiener Tonkünstlerorchester during his years at the Academy of Music, 1922 – 1934 Teacher at the Academy of Music / Course “Orchestral instruments”, from 1937 teacher Hugo Burghauser in the bassoon class, 1932 Shop steward Opera and committee member of the Vienna Philharmonic, 1932 – 1933 Deputy chairman, 1933 – 1938 Chairman of the Vienna Philharmonic Political functions at the time of Austrofascism: active member of the Vaterländische Front, 1934 – 1938 President of the Ring der Musiker, from 1935 appointed as expert witness for music at the Regional Court in Vienna Exile: flight from Vienna on 12 September 1938 to Toronto/Canada, later to New York Professional activities in exile: late 1938 – fall 1939 bassoonist in the Toronto Symphony Orchestra under Sir Ernest MacMillan, from roughly mid-1940 a brief spell of teaching at the “College for Music”/New York, 1941 – 1943 NBC Symphony Orchestra/New York under Arturo Toscanini, 1942 performances at the “Salzburg Chamber Festival” in Bernardsville/New Jersey founded by Burghauser, 1943 – 1965 Metropolitan Opera Orchestra under Edward Johnson, ab 1950 under Rudolf Bing Awards (selection): 1948 Nicolai medal in silver; 1961 Nicolai medal in gold, 1961 Honorary ring of the Vienna Philharmonic, 1967 Österr. -

Bruno Walter (Ca

[To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky Yale University Press New Haven and London Frontispiece: Bruno Walter (ca. ). Courtesy of Österreichisches Theatermuseum. Copyright © by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Sonia L. Shannon Set in Bulmer type by The Composing Room of Michigan, Grand Rapids, Mich. Printed in the United States of America by R. R. Donnelley,Harrisonburg, Va. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ryding, Erik S., – Bruno Walter : a world elsewhere / by Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references, filmography,and indexes. ISBN --- (cloth : alk. paper) . Walter, Bruno, ‒. Conductors (Music)— Biography. I. Pechefsky,Rebecca. II. Title. ML.W R .Ј—dc [B] - A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. For Emily, Mary, and William In memoriam Rachel Kemper and Howard Pechefsky Contents Illustrations follow pages and Preface xi Acknowledgments xv Bruno Schlesinger Berlin, Cologne, Hamburg,– Kapellmeister Walter Breslau, Pressburg, Riga, Berlin,‒ -

YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN Music Director Walter and Leonore Annenberg Chair

YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN Music Director Walter and Leonore Annenberg Chair Biography, February 2013 Yannick Nézet-Séguin triumphantly opened his inaugural season as the eighth music director of The Philadelphia Orchestra in the fall of 2012. From the Orchestra’s home in Verizon Hall to the Carnegie Hall stage, Nézet-Séguin’s highly collaborative style, deeply-rooted musical curiosity, and boundless enthusiasm, paired with a fresh approach to orchestral programming, have been heralded by critics and audiences alike. The New York Times has called Yannick “phenomenal,” adding that under his baton, “the ensemble, famous for its glowing strings and homogenous richness, has never sounded better.” In his first official season in Philadelphia, Yannick has taken the Orchestra to new musical heights in concerts at home, and has further distinguished himself in the community, with a powerful performance at the Orchestra’s annual Martin Luther King Tribute Concert, working with young musicians from the School District of Philadelphia’s All City Orchestra, establishing a relationship with the Curtis Institute, and ringing in 2013 with his Philadelphia audience with a festive New Year’s Eve concert. Following on the heels of a February 2013 announcement of a recording project with Deutsche Grammophon, Yannick and the Orchestra will record Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring together. Over the past decade, Nézet-Séguin has established himself as a musical leader of the highest caliber and one of the most exciting talents of his generation. Since 2008 he has been music director of the Rotterdam Philharmonic and principal guest conductor of the London Philharmonic, and since 2000 artistic director and principal conductor of Montreal’s Orchestre Métropolitain. -

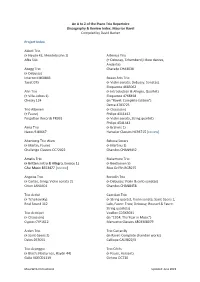

Ravel Compiled by David Barker

An A to Z of the Piano Trio Repertoire Discography & Review Index: Maurice Ravel Compiled by David Barker Project Index Abbot Trio (+ Haydn 43, Mendelssohn 1) Artenius Trio Afka 544 (+ Debussy, Tchemberdji: Bow dances, Andante) Abegg Trio Charade CHA3038 (+ Debussy) Intercord 860866 Beaux Arts Trio Tacet 075 (+ Violin sonata; Debussy: Sonatas) Eloquence 4683062 Ahn Trio (+ Introduction & Allegro, Quartet) (+ Villa-Lobos 1) Eloquence 4768458 Chesky 124 (in “Ravel: Complete Edition”) Decca 4783725 Trio Albeneri (+ Chausson) (+ Faure) Philips 4111412 Forgotten Records FR991 (+ Violin sonata, String quartet) Philips 4541342 Alma Trio (+ Brahms 1) Naxos 9.80667 Hanssler Classics HC93715 [review] Altenberg Trio Wien Bekova Sisters (+ Martin, Faure) (+ Martinu 1) Challenge Classics CC72022 Chandos CHAN9452 Amatis Trio Blakemore Trio (+ Britten: Intro & Allegro, Enescu 1) (+ Beethoven 5) CAvi Music 8553477 [review] Blue Griffin BGR275 Angelus Trio Borodin Trio (+ Cortes, Grieg: Violin sonata 2) (+ Debussy: Violin & cello sonatas) Orion LAN0401 Chandos CHAN8458 Trio Arché Caecilian Trio (+ Tchaikovsky) (+ String quartet, Violin sonata; Saint-Saens 1, Real Sound 112 Lalo, Faure: Trios; Debussy, Roussel & Faure: String quartets) Trio Archipel VoxBox CD3X3031 (+ Chausson) (in “1914: The Year in Music”) Cypres CYP1612 Menuetto Classics 4803308079 Arden Trio Trio Carracilly (+ Saint-Saens 2) (in Ravel: Complete chamber works) Delos DE3055 Calliope CAL3822/3 Trio Arpeggio Trio Cérès (+ Bloch: Nocturnes, Haydn 44) (+ Faure, Hersant) Gallo VDECD1119 Oehms