Closing the Migration-Trafficking Protection Gap: Policy Coherence in Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City and Delegate Profiles

City and Delegate Profiles 1 Bangladesh Benapole Benapole Pourashava (town) is located in Sharsha (Jessore district) about 7 km from Upazila headquarter and about 34 km from the district headquarter, Jessore. The Pourashava came into existence on 16th May 2006 as a `C’ Class Pourashava and became an `A’ Class Pourashava on 20 September 2011. The 2011 total population of the Pourashava is 88,672. Benapole Pourashava is governed by 1 Mayor and 12 Councilors – 9 male and 3 female. The Pourashava is spread over an area of 17.40 km2 and is divided into 9 wards consisting of 9 mouzas. Benapole Pourashava has regional significance because the Asian Highway and Railway line both pass through the Pourashava. The Pourashava faces many problems like the lack of planned residential areas, lack of electricity and safe drinking water, traffic congestion, lack of community facilities, lack of infrastructure facilities, and poor capacity of the Pourashava administration etc. Population size 88,672 Land area (km2) 17.4 Population density (per km2) 5,096 Md. Asraful Alam Liton Mayor, Benapole Municipality He is a businessman by profession and became the Mayor of Benapole in February 2011. South-South City Leaders’ Forum 2014 2 Bangladesh Chuadanga Chuadanga District was a sub-division of former Kushtia District and was upgraded to a District on 26th February, 1984. It was raised to the status of a Municipality in 1972 and became a “B” class Municipality in 1984. At that time, Chuadanga Municipality had an area of 32.67 km2 with three wards and 13 mahallas. It was upgraded to an “A” class Municipality in 1995 with an area of 37.39 km2, consisting of 9 wards, 41 mahallas, 13 mouzas and 71 mouza sheet (BBS-2001). -

Download the Entire Publication As

The Heinrich Boell Foundation (HBF), affiliated with the Green Party and headquartered in Berlin, is a legally independent political foundation working in the spirit of intellectual openness. Its activities encompass more than 130 projects in 60 countries that have been developed with local partners. The Foundation's primary objective is to support political education both within Germany and abroad, thus promoting democratic involvement, socio-political activism, and cross-cultural understanding. The Foundation also provides support for art and culture, science and research, and developmental co- operation. HBF's activities are guided by the fundamental political values of ecology, democracy, solidarity, and non-violence. The German Institute for International and Security Affairs of the Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP) is an independent scientific establishment that conducts practically oriented research on the basis of which it then advises the Bundestag (the German parliament) and the federal government on foreign and security policy issues. A traditional Myanmarese/Burmese painting (circa 1880) depicting the King and Queen holding a For further information please visit: 'Hluttaw' or parliament meeting with four Chief Ministers and other palace officials in the absence of their www.boell.de subjects or representatives. www.swp-berlin.de (Victoria and Albert Museum, Great Britain; http://www.vam.ac.uk/) Active Citizens Under Political Wraps: Experiences from Myanmar/Burma and Vietnam Active Citizens Under Political Wraps: Experiences from Myanmar/Burma and Vietnam Edited by the Heinrich Boell Foundation Southeast Asia Regional Office First edition, Thailand, Chiang Mai 2006 © Heinrich-Boell-Stiftung Photo Front Page: Traditional Myanmarese/Burmese painting (parabeik), circa 1880 © Photo Back Page: Martin Grossheim Printing: Santipab Pack-Print, Chiang Mai, Thailand Copyeditors: Zarni, JaneeLee Cherneski, Yong-Min (Markus) Jo ISBN 974-94978-3-X Contact Address: Heinrich Boell Foundation Southeast Asia Regional Office P.O. -

Myanmar Coup and Internet Shutdowns

Briefing Note 1 February - 31 March 2021 Myanmar Coup and Internet Shutdowns Overview On 1 February 2021, the Myanmar military junta, alleging widespread voter fraud Asia Centre’s Briefing Note, Myanmar staged a coup and took political control of the country. They did so after months- Coup and Internet Shutdowns, tracks the period 1 February to 31 March long refusal to accept the National League for Democracy’s (NLD) victory in the 2021. The Note provides a timeline of 2020 general election (Reuters, 2021). A one-year public emergency was the shutdowns, reactions from declared under section 417 of the 2008 Constitution. Since 1 February, the protestors, technology companies and the international community, legal military junta has shut down the internet, blocked access to online sites, disabled analysis of key laws and Myanmar’s mobile internet access, closed down media companies and arrested online international obligations. Over the dissenters and journalists as the protests continue into April 2021. There has course of the coup, it records a shift in been an intensification of internet and media control with the aim of crippling the tactics by the military junta from internet content censorship to internet protests and halting the spread of pictures and videos of security personnel using infrastructure control. Asia Centre will disproportionate force against protestors. What we see in Myanmar is a shift in continue to track developments related tactics by the military junta from internet content censorship to infrastructure to internet -

The Brookings Institution

MYANMAR-2021/07/22 1 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION WEBINAR THE QUAGMIRE IN MYANMAR: HOW SHOULD THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY RESPOND? Washington, D.C. Thursday, July 22, 2021 PARTICIPANTS: JONATHAN STROMSETH Senior Fellow Lee Kuan Yew Chair in Southeast Asian Studies, Foreign Policy The Brookings Institution AYE MIN THANT Features Editor Frontier Myanmar Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Formerly at Reuters MARY CALLAHAN Associate Professor Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies University of Washington DEREK MITCHELL President National Democratic Institute for International Affairs Former U.S. Ambassador to Myanmar (Burma) KAVI CHONGKITTAVORN Senior Fellow Institute of Security and International Studies Chulalongkorn University’ Columnist Bangkok Post * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 1800 Diagonal Road, Suite 600 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 MYANMAR-2021/07/22 2 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. STROMSETH: Greetings. I’m Jonathan Stromseth, the Lee Kuan Yew Chair in Southeast Asian Studies at Brookings and I’m pleased to welcome everyone to this timely event, the quagmire in Myanmar: How should the international community respond? Early this year, the Burmese military also known as the Tatmadaw detained State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi and other civilian leaders in a coup d’état ending a decade of quasi- democracy in the country. The junta has since killed hundreds of protestors and detained thousands of activists and politicians, but mass protests and mass civil disobedience activities continue unabated. In addition, a devasting humanitarian crisis has engulfed the country as people go hungry, the healthcare system has collapsed and COVID-19 has exploded adding a new sense of urgency as well as desperate calls for emergency assistance. -

Peopling the Northeast: Part 5

54 neScholar 0 vol 3 0 issue 3 Peopling of the Northeast Tanmoy Bhattacharya Teaches at Centre of Part 5 Advanced Studies in Linguistics Faculty of Arts, University of Delhi & Chief Editor of Indian Linguistics S I was returning from the 23rd version of during the Air-India flight from Guwahati to Delhi, when the Himalayan Languages Symposium, my teacher and ex-colleague from the University of Delhi held from 5th to 7th July, I had this and a well known expert on Tibeto-Burman linguistics, nagging feeling that I am not yet done Prof.K.V.Subbarao, who thinks of and analyses linguistic with the story of peopling of the data even in his sleep, sitting across the aisle, expressed Northeast of India, published in four his surprise at many young scholars classifying Meeteilon instalments in the previous four issues of this increasingly in the Kuki-Chin subgroup of Tibeto-Burman, in several popularA journal (see vol. 2, issues 3-4, 2016; and vol. talks in the Symposium. 3, issues 1-2, 2017). My hunch was confirmed and transformed into an overlapping series of echoes of bells N fact, more than a century ago, the visionary linguist ringing in the ancient corridors of history, as soon as the IGeorge Abraham Grierson had the same doubt as early seat-belt signs were turned off after reaching 20,000 feet as 1904: 54 neScholar 0 vol 3 0 issue 3 neScholar 0 vol 3 0 issue 2 55 PEOPLING OF NE INDIA I HERITAGE “The Kuki-Chin languages must be subdivided in issue better. -

The Impact of Censorship on the Development of the Private Press Industry in Myanmar/Burma

Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper University of Oxford The Impact of Censorship on the Development of the Private Press Industry in Myanmar/Burma by Kyaw Thu Michaelmas 2011 & Hilary 2012 Sponsor: Thomson Reuters Foundation 1 Acknowledgements This study would not have been possible without the support of several people who have generously assisted me throughout my study. First and foremost, I would like to thank the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) and the Thomson Reuters Foundation for giving me the valuable opportunity to study at the University of Oxford. I would like to thank James Painter and Dr. Peter Bajomi-Lazar for their good guidance and encouragement. I also thank RISJ director David Levy and staff at the RISJ - Sara Kalim, Alex Reid, Rebecca Edwards and Kate Hanneford-Smith - for their support during my fellowship period. In addition, I would to thank Professor Robert H. Taylor and Dr. Peter Pritchard for their useful advice. Last but not least, I would like to thank my fellow journalists from Myanmar for participating in my survey and the publishers who gave me interviews for this research paper. Information on the use of country name The use of the country name of Myanmar has been controversial among the international community since the military government changed the names of the country and cities in 1988. From that point on, Burma officially became Myanmar and Rangoon became Yangon. In this paper, I will use Burma when I refer to the period before the junta changed the name and use Myanmar for the later period. -

A Geographic Study on Migration Process of Mandalay City

Title A Geographic Study on Migration in Mandalay City Author Dr. May Thu Naing Issue Date 2008 A Geographic Study on Migration in Mandalay City May Thu Naing 1 ABSTRACT This research is focused on migration in Mandalay City. According to the data gathered from Immigration and Population Department, 5 wards which have maximum numbers of immigrants and another 5 wards which have minimum numbers of immigrants were selected. The data required for this research were collected by using questionnaires from these 10 wards in five townships. Among these wards, sample of 1789 respondents, who were the immigrants in Mandalay City, were interviewed. The results showed that migration process depends on various reasons. Most of the responses showed that the immigrants wanted to get better environment of Mandalay City related to job, business, education and health opportunities and security.These factors directly influenced on the migration in Mandalay City. In that migration, both pull factors and push factors are interrelated . Introduction Objectives Main objectives of this research are:- 1. To study the effects of migration in the urban growth of Mandalay City 2. To emphasize on push and pull factors of migration into Mandalay City 3. To search for a relationship between immigration and urban expansion of Mandalay City . Methodology To depict a general picture of migration, secondary data are obtained from various offices, institutions and departments. Primary data and information are gathered by questionnaires and interviews in both structured and semi-structured forms. Several field observations were done for both urban areas and rural areas. In urban areas, samples are selected by using Random Sampling Method. -

Myanmar Woodfuels Sector Assessment

Public Disclosure Authorized MYANMAR WOODFUELS SECTOR Public Disclosure Authorized ASSESSMENT JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: AUS0001529 . Myanmar Country Forest Note WOODFUELS SECTOR ASSESSMENT . June 2020 . Environment, Natural Resources and The Blue Economy Global Practice . © 2020 The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: “World Bank. 2020. Myanmar Woodfuels Sector Assessment. © World Bank.” All queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: [email protected]. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................................. -

Myanmar (Formerly Burma) Pronounce Its Name Correctly (MEE-Ah-Mah) and You’Ll Be Sure to Impress the Locals!

Myanmar (formerly Burma) Pronounce its name correctly (MEE-ah-mah) and you’ll be sure to impress the locals! Note: Myanmar is still a country in transition as it opens up to more foreign visitors, and so travel information to the country is quite changeable. Visas Tourist visas are single entry only and allow you to stay in Myanmar for 28 days. They have to be used within a 90-day window after they are issued. You always need a visa in advance of coming to Myanmar. The visa fee is $20. You can apply for the visas online through the Myanmar Embassy’s website, which has more information about visa requirements (http://www.mewashingtondc.com/visa_form_1_en.php). Climate The climate in Myanmar varies depending on elevation, but most of the country is considered tropical or subtropical. There are three distinct seasons: Cold dry season November - February 68° - 75° F Hot dry season March - April 86° - 95° F Hot wet season May - October 77° - 86° F From June to August, rainfall can be constant for long periods of time, particularly on the Bay of Bengal coast, and in Yangon and the Irrawaddy Delta. The rain is less intense in September and October. For these reasons, more tourists travel to Myanmar during the cold dry season. During those months, accommodations are more limited and potentially more expensive. Try booking ahead to avoid paying high prices for last-minute rooms. The hot muggy weather keeps many tourists away in other seasons, making some prices lower and accommodations easier to come by. As a general rule, temperatures and humidity become lower at higher altitudes. -

Project Document

United Nations Development Programme Country: Myanmar PROJECT DOCUMENT1 Project Title: Addressing Climate Change Risks on Water and Food Security in the Dry Zone of Myanmar UNDAF Outcome(s): UNDP Strategic Plan Environment and Sustainable Development Primary Outcome: Reduced vulnerability to natural disasters and climate change, and the promotion of energy conservation through access to affordable and renewable energy, particularly in off-grid local communities. Expected CP Outcome(s): Reduced vulnerability to natural disasters and climate change, improved environmental and natural resource management, and the promotion of energy conservation through access to affordable and renewable energy, particularly in off-grid local communities. Expected CPAP Output (s) Capacities to adapt to climate change and reduce disaster risk. Executing Entity/Implementing Partner: UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Implementing Entity/Responsible Partners: MULTILATERAL IMPLEMENTING ENTITY Brief Description The Dry Zone is one of the most climate sensitive and natural resource poor regions in Myanmar and vulnerable to growing food insecurity and severe environmental degradation. The objective of the proposed project is to reduce the vulnerability of farmers in Myanmar’s Dry Zone to increasing drought and rainfall variability, and enhance the capacity of farmers to plan for and respond to future impacts of Climate Change on food security. The proposed project is addressing climate risk resilience through community based and community driven adaptation in -

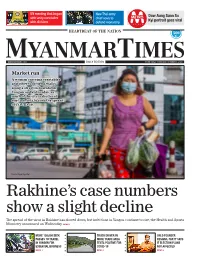

Rakhine's Case Numbers Show a Slight Decline

UN meeting that began New Thai army Daw Aung Sann Su with unity concludes chief vows to with divisions defend monarchy Kyi portrait goes viral HEARTBEAT OF THE NATION 500 Ks. WWW.MMTIMES.COM DAILY EDITION ISSUE 1382 | THURSDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2020 Market run A woman carrying vegetables and other food items walks along a street in downtown Yangon on Wednesday, as much of the city is shuttered due to efforts to curb the spread of COVID-19. Photo: Nyan Zay Htet Rakhine’s case numbers show a slight decline The spread of the virus in Rakhine has slowed down, but infections in Yangon continue to rise, the Health and Sports Minnistry announced on Wednesday. NEWS 3 MORE 100,000 SEEK TRUCK DRIVER IN SNLD FOUNDER PASSES TO TRAVEL MUSE TRADE AREA RESIGNS, PARTY SAYS IN YANGON FOR TESTS POSITIVE FOR IT ELECTION PLANS ESSENTIAL BUSINESS COVID-19 NOT AFFECTED NEWS 3 NEWS 3 NEWS 4 2 THE MYANMAR TIMES OCTOBER 1, 2020 Facts and figures for COVID-19 COVID-19 cases in Myanmar Trendline for COVID-19 cases in Myanmar 15000 Confirmed cases 13,373 10000 Deaths from virus confirmed Recovered by tests 310 3,755* 5000 Number of people who tested negative for COVID-19 296,041 Source: Ministry of Health and Sports, Myanmar Graphic: Khin Zaw/The Myanmar Times 0 01/04/2020 01/05/2020 01/06/2020 01/07/2020 01/08/2020 01/09/2020 COVID-19 cases in Rakhine State by township COVID-19 infections in Rakhine State 15000 Sittwe 871 Kyauk Phyu 209 Mrauk-U 106 Maungdaw 69 Kyauktaw 65 10000 Pauk Taw 55 Buthidaung 42 Min Byar 40 Myae Pon 30 Phonnar Kyun 28 5000 Thandwe 12 Toungup -

Briefing Note 1-15 February 2021

Briefing Note 1-15 February 2021 Myanmar Coup and Internet Shutdowns Overview On 1 February 2021, the Myanmar military junta, alleging widespread voter fraud Asia Centre’s Briefing Note, Myanmar staged a coup and took political control of the country. They did so after months- Coup and Internet Shutdowns, pulls together key information related to the long refusal to accept the National League for Democracy’s (NLD) victory in the internet shutdowns following the military 2020 general election (Reuters, 2021). A one year public emergency was takeover of the country. Covering the declared under section 417 of the 2008 Constitution. period 1-15 February 2021, the Note provides a timeline of the shutdowns, citizen reactions, statements by technology companies, legal analysis of Internet Shutdown key laws and Myanmar’s international human rights obligations. Asia Centre On the day of the coup, the Myanmar Times reported: “access to TV channels, will continue to track developments phone lines and Internet service have been cut” (Kang, 2021). The Tatmadaw related to internet freedoms in Myanmar imposed internet shutdowns across major cities such as Naypyidaw, Yangon, and and Southeast Asia. Mandalay. Using Section 77 of the country’s Telecommunication Law (2013), the military junta compelled Telcos and Internet Service Providers (ISPs) such as Telenor Myanmar, Ooredoo Myanmar, Myanmar Post and Telecommunication Asia Centre (MPT), Mytel, Welink, 5BB and Frontiir to adhere to their demands of service Asia Centre disruption. The Section gives the government the authority to direct ISPs to Asia Centre “suspend a telecommunication service or restrict specific forms of communication” @asiacentre_org on the occurrence of public emergency (Telecommunications Law, 2013).