Frederic Remington's East Legacy Exhibition Gallery Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ten Year Strategic Action Plan

PLANDOWNTOWN 2023 FORT WORTH TEN YEAR STRATEGIC ACTION PLAN 1 12 SH Uptown TRINITY Area ch ea W P UPTOWN S a 5 m u 3 e l - Trinity s H S I H Bluffs 19 9 M Northeast a in Edge Area Tarrant County t 1s Ex Courthouse Expansion d Area 3 2n rd EASTSIDE 3 h ap 4t lkn Be Downtown S f h P r C 5t H he at o U e e Core m n W d M m R e a e h r i r t s n c 6 o H e n o 2 u Southeast T s 8 h t th r o 7 o n 0 c k Edge Area m o h r t t 8 o n ITC h 9t CULTURAL 5th Expansion 7th 7th DISTRICT Burnett Area 2 Henderson- Plaza 10th vention Center Summit J City o n e Hall s Texas H C o e C m n h S d m e u e r e m r r r y s c m e o i n t Expansion Area 1 Lancaster J Lancaster e Lancaster n n i n g s d lv B k r a Holly P t s e Treatment IH-30 r o F Plant Parkview SOUTHEAST Area NEAR FORT SOUTHSIDE WORTH Table of Contents Message from Plan 2023 Chair 1 Executive Summary 2 The Plan 4 Vision 10 Business Development 16 Education 24 Housing 32 Retail, Arts and Entertainment 38 Transportation 42 Urban Design, Open Space and Public Art 50 Committee List, Acknowledgements 62 Message from Plan 2023 Chair Since the summer of 2003, Downtown Fort Worth has made advance - ments on many fronts. -

HOWDY and Welcome from the NAPO-DFW (Dallas/Ft. Worth) Chapter!

HOWDY and welcome from the NAPO-DFW (Dallas/Ft. Worth) Chapter! Everything IS bigger in Texas, but never fear, this information will help you find your way around while you're here for NAPO2019 Annual Conference! • Conference App: You will receive the link to download the NAPO2019 app from NAPO in March. The app can be downloaded from your app/play store. • NAPOCares: The 2019 NAPOCares recipient for 2019 is the Presbyterian Night Shelter in Fort Worth. You can participate by purchasing an item from their Amazon Wish List or by making a direct donation. • Conference Location: The Worthington Renaissance Hotel Fort Worth is the main conference hotel. Due to high demand of rooms we have added overflow rooms at the Courtyard Fort Worth Blackstone. • Dress Code: Recommended conference attire is always business casual. Keep in mind: o Most hotels have a cooler temperature setting so we recommend bringing a sweater or light jacket. o Please remember to be courteous and honor NAPO’s fragrance-free policy. • Parking: The Renaissance Hotel Fort Worth offers parking and it is $28/day. • Transportation: No shuttle service is provided by the hotel. Transportation options include: ▪ From Dallas Fort Worth International Airport o Airport Super Shuttle (reservations required) $24 o Taxi stations, Lyft and Uber are available o Trinity Metro TexRail $2.50 o Go to Terminal B in DFW Airport (use Skylink Train to transfer to Terminal B if needed). Take the Trinity Metro TexRail to the Downtown ITC (Intermodal Transportation Center)/Fort Worth Station. Take -

READ ME FIRST Here Are Some Tips on How to Best Navigate, find and Read the Articles You Want in This Issue

READ ME FIRST Here are some tips on how to best navigate, find and read the articles you want in this issue. Down the side of your screen you will see thumbnails of all the pages in this issue. Click on any of the pages and you’ll see a full-size enlargement of the double page spread. Contents Page The Table of Contents has the links to the opening pages of all the articles in this issue. Click on any of the articles listed on the Contents Page and it will take you directly to the opening spread of that article. Click on the ‘down’ arrow on the bottom right of your screen to see all the following spreads. You can return to the Contents Page by clicking on the link at the bottom of the left hand page of each spread. Direct links to the websites you want All the websites mentioned in the magazine are linked. Roll over and click any website address and it will take you directly to the gallery’s website. Keep and fi le the issues on your desktop All the issue downloads are labeled with the issue number and current date. Once you have downloaded the issue you’ll be able to keep it and refer back to all the articles. Print out any article or Advertisement Print out any part of the magazine but only in low resolution. Subscriber Security We value your business and understand you have paid money to receive the virtual magazine as part of your subscription. Consequently only you can access the content of any issue. -

Planning for Learning on a BISD Field Trip

Planning for Learning on a BISD Field Trip Any learning experience must be tied to the BISD grade level curriculum and include pre, during, and post activities. Here are some suggested activities: Preparing students before the trip: 1. Discuss the purpose of the trip and how it related to the standards. 2. Introduce vocabulary words that will be used by docents during the field trip. 3. Show photographs or posters of the field trip site or related exhibits that will be viewed. 4. Explore the Website of the location you will be visiting. 5. Discuss with students how to ask good questions and brainstorm a list of open-ended observation questions to gather during the field trip. Activity suggestions that might be appropriate during the trip: 1. Students complete sketch pages with partial drawings of objects found in exhibits for students to complete the drawings based on their observations. 2. Students complete field notebooks for recording answers to prepared questions. 3. Students complete hand drawn postcards to write near the end of the tour that will summarize the field trip visit. Follow up activities after the trip: 1. Provide time for students to ask questions, record key words, ideas and phrases as journal entries. 2. Provide time for students to share general observations and reactions to the field trip 3. Create a classroom bulletin board displaying materials developed or collected while on the field trip 4. Develop a classroom museum that replicates and extends displays students observed on the field trip. 5. Develop a vocabulary list based on field trip observations 6. -

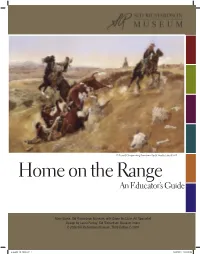

Home on the Range an Educator’S Guide

C. Russell, Cowpunching Sometimes Spells Trouble (detail) 1889 Home on the Range An Educator’s Guide Mary Burke, Sid Richardson Museum, with Diane McClure, Art Specialist Design by Laura Fenley, Sid Richardson Museum Intern © 2004 Sid Richardson Museum, Third Edition © 2009 Home09_10_2010.indd 1 9/10/2010 1:53:18 PM Home on the Range Page numbers for each section are listed below. Online version – click on the content title below to link directly to the first page of each section. For an overview of the artworks included in this booklet, see Select a Lesson – Image List, page 30. Contents Introduction to Home on the Range 4 Sid W. Richardson 6 The Museum 10 Fredric S. Remington 12 Charles M. Russell 14 Timeline (Artists, Texas, U.S. History) 16 Select a Lesson – Image List 30 Lesson Plans 32 Student Activities 52 Teacher Resources 62 2 Home on the Range Sid Richardson Museum Home09_10_2010.indd 2 9/10/2010 1:53:18 PM Sid W. Richardson Sid W. About the Educator’s Guide This Educator’s Guide is a resource for viewing and dialogue containing questions to direct classroom The Museum interpreting works of art from the Sid Richardson Museum discussion and engage students in their exploration in the classroom environment. The images included in the of the artworks, background information about Guide have been selected to serve as a point of departure the artists and the works of art, vocabulary, and for an exploration of the theme of the cowboy way of life. suggestions for extension activities • Student Activities – activities that can be used to The background materials (timelines, biographies, complement classroom discussion about these (or bibliography and resources) are appropriate for educators other) artworks The Artists of all levels. -

Building a Christian Community Where People Are Transformed by the Love of Christ. Bring Others to Christ Belong to a Communit

ubcfortworth.org University Baptist Church offers a welcoming community of faith where people are genuine and accept others for who they are. We are aware of our need for a Savior and support one another as we seek to be transformed by the Lord. Building a Christian community where people are transformed by the love of Christ. Bring others to Christ Belong to a community of faith Believe in Christ Become disciples • Introducing Jesus as Savior and Lord through outreach and evangelism—Acts 1:8; 1 Peter 3:15 • Meeting the needs of others in Jesus' name—Matthew 25:34-46; 1 John 3:17-18 • Welcoming all people in a fellowship characterized by love and grace— John 13:34-35; James 2:1-13 • Reflecting Christ in actions and attitudes—Philippians 2:1-5, Colossians 3:12-14 • Making Disciples—Matthew 9:36-38; 28:18-20 • Teaching and preaching centered in the Bible— Psalm 119:105; 2 Timothy 3:16-17 • Supporting and participating in local and world missions—Romans 10:14-15; 2 Corinthians 9:7-8 We are committed to the “Priesthood of Believers”—the competency of every Christian man and woman to understand Scripture, empowered by the Holy Spirit, and go directly to God in prayer. We are committed to supporting the ministry of both men and women equally in leadership roles throughout our congregation. We ordain both men and woman as full time ministers and deacons, as God leads them and our church. We are committed to mission in word and action. We seek to be in ministry with our community and our world through evangelism—sharing the Good News of Jesus Christ, and outreach—seeking to address the spiritual and physical needs of others for community transformation. -

Fort Worth on a BUDGET ITINERARY

Fort Worth ON A BUDGET ITINERARY • Many of the city’s world-class museums offer free admission • Just north of to their permanent collections and activities. The Amon Carter downtown is Fort Museum of American Art houses a stunning collection of 19th Worth’s Stockyards and 20th century paintings, sculpture, works on paper, and National Historic photography – and it’s all free of charge. Admission to the District. Walk permanent collection at the Kimbell Art Museum and admission through Stockyards to the Sid Richardson Museum are always free. The Modern Art Station and visit the Museum of Fort Worth offers free admission on the first Sunday of Stockyards Museum every month and half-price on Wednesdays. for just $2. Don’t miss the Fort Worth Herd, the world’s only twice-daily cattle drive every day at 11:30 a.m. and 4 p.m. • Tour the Bureau of Engraving and Printing’s Western Currency Facility, one of only two U.S. Department of Treasury locations that prints money, and it won’t cost a dime to see billions of dollars being printed. During the 45-minute guided tour visitors can see each step of currency production, beginning with large blank sheets of paper and ending with wallet ready bills. • Enjoy Fort Worth’s green space at Trinity Park, along the banks of the Trinity River, which is home to a duck pond, miniature train, playgrounds and the Trinity Trails. With picnic areas and restrooms scattered throughout, it is the perfect venue for get-togethers with family and friends. • For more outdoor fun, hike along miles of trails at the Fort Worth Nature Center and Refuge. -

Explore Fort Worth Tms & Alliance

So Many Districts. So Much to See. So Much to Do! VISITORS GUIDE EXPLORE FORT WORTH TMS & ALLIANCE Shopping, Dining Museum Mecca STOCKYARDS & Entertainment D/FW INTL AIRPORT PANTHER ISLAND RIVER DISTRICT WEST 7TH SUNDANCE SQUARE & DOWNTOWN CULTURAL DISTRICT NEAR SOUTHSIDE CAMP BOWIE CULTURAL DISTRICT WESTBEND The Cultural District features five internationally- SUNDANCE SQUARE & DOWNTOWN recognized museums: Kimbell Art Museum, Modern Art CLEARFORK Fort Worth’s city center buzzes day and night. It’s one of the cleanest Museum of Fort Worth, Amon Carter Museum most walkable urban areas you’ll find anywhere. The heart of downtown of American Art, National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of TCU & ZOO is Sundance Square, a 35-block shopping and entertainment district Fame and Fort Worth Museum of Science and History. Stroll where twinkling lights line sidewalks around beautifully restored through tree-lined streets while admiring the architecture For more information, including hotels, dining, events, buildings. Come meet the locals among restaurants, shops, galleries, Bass of the museums and the adjacent, art deco Will Rogers WATERSIDE coupons and more, please visit: FORTWORTH.COM Performance Hall and live theatre. FortWorth.com/SundanceSquare Memorial Center. FortWorth.com/CulturalDistrict TEXAS MOTOR SPEEDWAY & Boutiques on the Bricks Start Your Engines ALLIANCE African Savanna This growing area just north of downtown BILLY BOB'S TEXAS offers high-speed thrills at Texas Motor Speedway, one of the best and largest sports stadiums in the U.S. and home to the world’s largest HD video screen, nicknamed “Big Hoss.” Enjoy shopping at nearby Tanger Outlets. See YEAR-ROUND FUN IN THE CITY WHERE THE WEST BEGINS millions of dollars made before your eyes at the Dates available at time of printing. -

Downtown Fort Worth

System INTERMODAL TRANSPORTATION CENTER (ITC) STATION WHERE TO BOARD YOUR BUS Route Board at Map Spur* East Lancaster H This service is designed to help employers 1 Hemphill G incorporate commuter benefits into their 2 Camp Bowie C benefits plan. For more information, contact FWTA at (817) 215-8700 or ask your Human 3 South Riverside / TCC South Campus J Resources representative. AMTRAK / TRE BOARDING PLATFORMS 4 East Rosedale L 5 (a) Evans Avenue / (b) Glen Garden I 6 8th Avenue/McCart/Hulen Mall D Contact us 7 University A A B C D E 8 Riverside/Evans J 7, 18 15 2 6 14 ITC MAIN BUILDING 9 Ramey/Vickery M Customer Service Info Center 10 Bailey S6 (817) 215-8600 4 L 5 a.m. to 10 p.m. Monday through Friday F G H I J K 11 North Beach/Heritage Trace K 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. Saturday 46 1 Spur 5 3, 8 11 12 Samuels/Mercantile Center S5 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Sunday 14 North Riverside E Kiss & Ride Drop Off The Customer Service kiosk, inside the FWTA information 15 Stockyards/North Main B Intermodal Transportation Center (ITC) and customer service 9 M 18 Safari Shuttle (Seasonal) A at 1001 Jones St., Fort Worth, TX Amtrak 46 Jacksboro Highway F 6 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday EFFECTIVE AUGUST 2017 13, Customer Service (817) 215-8600 Enterprise 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Saturday 57 Como/Montgomery S7 Closed on Sunday TTY-TDD (817) 215-8686 Subway Jones St Curbside Stops 60 Eastside Express S2 Fort Worth Transportation Authority Customer Service Retail and Bulk Sales 800 Cherry St. -

Cultural District Walking Map

CULTURAL DISTRICT WALKING MAP B Camp Bowie To West 7th & Downtown B 1 ii iv 13 gers 9 vii Ro v Will 10 i 8 iii iv Cliburn n Va ontgomery Darnell M viii To y 12 Landsford W I-30 ill a Ro gers Gend To b Downtown 7 15 Lancaste c d r ix hnson xi Jo 11 Rip e 4 B Burnett Tand y f 6 j g i 5 Harley h k ersity x Univ Trail e g Cr a e l st l lin i e V in b a C g 3 o L d n a o o Z h t r o W t r o F o T 2 Trinity Trails B Conservatory DECEMBER 12, 2018 ★ rth To Wo I-30 rt 14 Fo Copyright © Visit 1 Amon Carter Museum of American Art 8 Fort Worth Community Arts Center 15 Will Rogers Memorial Center Outdoor Sculptures: 3501 Camp Bowie Blvd. 817.738.1933 1300 Gendy St. 817.738.1938 3401 W. Lancaster Ave. 817.392.7469 i “Vortex,” Richard Serra 2 Fort Worth Botanic Garden / Japanese Garden 9 Kimbell Art Museum a Pioneer Tower ii “Two-Piece Reclining Figure,” Henry Moore 3220 Botanic Garden Blvd. 817.392.5510 3333 Camp Bowie Blvd. 817.332.8451 b Will Rogers Auditorium “Woman Addressing The Public,” Joan Miró 3 Botanical Research Institute of Texas (BRIT) 10 Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth iii c Amon G. Carter Jr. Exhibits Building 1700 University Drive 817.332.4441 3200 Darnell St. 817.738.9215 iv “Constellation,” Isamu Noguchi d Will Rogers Coliseum 4 Casa Mañana 11 National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame v “Figures in a Shelter,” Herny Moore e 3101 W. -

IN FORT WORTH Want to Enjoy Fort Worth Without Spending a Lot of Money? Use This Handy Guide to Discover Free Things to Do and See Around Our City

FUN & FREE IN FORT WORTH Want to enjoy Fort Worth without spending a lot of money? Use this handy guide to discover free things to do and see around our city. You’ll find that Fort Worth offers plenty of value if you’re on a budget! Fort Worth Water Gardens This beautiful, refreshing oasis is located adjacent to the Fort Worth Convention Center. Designed by Phillip Johnson, the Fort Worth Water Gardens is an architectural and engineering marvel. Experience a variety of water features as you stroll through this relaxing urban park. 1502 Commerce Street • 817.392.7111 www.FortWorth.com Heritage Trails Take a walk through downtown and discover the people and events that shaped Fort Worth’s rich history. Have your picture taken with our sleeping panther and then visit each permanent bronze-plaque detailing DOWNTOWN/SUNDANCE SQUARE historic events. STOCKYARDS NATIONAL HISTORIC DISTRICT Downtown Fort Worth • 817.338.3330 If you haven’t been to downtown Fort Worth, prepare www.fortworthheritagetrails.com Once a major stop on the legendary Chisholm Trail, to be amazed. It’s a glittering urban oasis – one of the Fort Worth is the finest place in America to experience most exciting and pedestrian-friendly downtown areas our nation’s proud Western heritage. This District offers in America. Don’t miss the 35-block Sundance Square 15 blocks of tradition, nightlife, shopping and family fun. entertainment and shopping district, where both locals and visitors go for food and fun. Arrival of Grapevine Vintage Railroad Bass Performance Hall Tours Watch the historic locomotive roll into The crown jewel of downtown Fort Worth, the Stockyards Station from Grapevine. -

Fort Worth Destination Guide

Where the WEST Begins FORT WORTH STOCKYARDS NATIONAL HISTORIC DISTRICT TO EXPERIENCE AMERICA’S TOP DOWNTOWN Fort Worth has the #1 downtown in America, according to livability.com – and Sundance Square is the heart of downtown. This is the place to have a wonderful meal, shop at unique stores, see a great show and relax in Sundance Square Plaza. You can even park for free! Get all the details at sundancesquare.com. CONTENTS FORT WORTH DESTINATION GUIDE FORT WORTH CONVENTION & VISITORS BUREAU Bob Jameson, President and CEO Mitch Whitten, Vice President Marketing & Communications Jessica Dowdy, CTA Director, Public Relations Tom Martens, CTA, Art Director McKenzie Zieser, CTA Web Specialist & Content Editor Sarah Covington, CTA Public Relations Coordinator PUBLISHED BY Sales: Jamie May-Barson Phone: 800-683-0010 milespartnership.com PUBLICATION TEAM Content Directors Lisa Pogue, Vanessa Day WELCOME Art Director Hilary Stojak Contributing Writers Drew Harris, 3 Explore Fort Worth Chris Kelly, June Naylor, Brian Pierce SALES DISTRICTS Account Executive Jamie May-Barson SUPPORT AND LEADERSHIP 6 Stockyards National 18 TCU / Zoo Account Director Rachael Root Historic District 22 West 7th Advertising Coordinators 8 Cultural District 24 Camp Bowie Hanna Berglund, Nadine Rebrovic 14 Downtown / 26 TMS/Alliance CEO/President Roger Miles Sundance Square 26 Nearby 16 Near Southside CFO Dianne Gates COO David Burgess Senior Vice President Jay Salyers FORT WORTH FUN IMAGES 34 Food & Drink Provided by the Fort Worth 12 Performing Arts 36 Day Trips Convention & Visitors Bureau 28 Sports 30 Outdoor Recreation 38 Made in Fort Worth The Fort Worth Destination Guide is a publication 40 Convenient Travel of the Fort Worth Convention & Visitors Bureau.