Podolsky V. Cadillac Fairview Corp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada-2013-Finalists.Pdf

TRADITIONAL MARKETING ADVERTISING Centres 150,000 to 400,000 sq. ft. of total retail space Identity Crisis Rescued 10 Dundas East Toronto, Ontario Management Company: Bentall Kennedy (Canada) LP Owner: 10 Dundas Street Ltd. One World in the Heart of Your Community Jane Finch Mall Toronto, Ontario Management Company: Arcturus Realty Corporation Owner: Brad-Jay Investments Limited At the Heart of the Community Les Galeries de Hull Gatineau, Quebec Management Company/Owner: Ivanhoe Cambridge Here’s to the Best Things in Life Lynden Park Mall Brantford, Ontario Management Company/Owner: Ivanhoe Cambridge Must Visit MEC Montreal Eaton Centre Montreal, Quebec Management Company/Owner: Ivanhoe Cambridge Centres 400,000 to 750,000 sq. ft. of total retail space Break Out Your Style Cornwall Centre Regina, Saskatchewan Management Company: 20 Vic Management Inc. Owner: Kingsett Capital & Ontario Pension Board The Really Runway Dufferin Mall Toronto, Ontario Management Company: Primaris Management Inc. Owner: H&R Reit Les Rivieres: Inspired by Trends Les Rivières Shopping Centre Trois-Rivières, Quebec Management Company: Ivanhoe Cambridge Owner: Ivanhoe Cambridge & Sears Canada Medicine Hat Mall Motherload Medicine Hat Mall Medicine Hat, Alberta Management Company: Primaris Management Inc. Owner: H & R Reit Crate&Barrel | OAKRIDGE · SINCE MARCH 21, 2013 Oakridge Centre Vancouver, British Columbia Management Company/Owner: Ivanhoe Cambridge Wahoo! Uptown Victoria, British Columbia Management Company: Morguard Investments Limited Owner: Greystone Centres 750,000 to 1,000,000 sq. ft. of total retail space Entrepôts de Marques - Brand Factory Marché Central Montréal, Québec Management Company: Bentall Kennedy (Canada) LP Owner: bcIMC Realty Corporation The World Of Fashion In 200 Stores Place Rosemère Rosemère, Québec Management Company: Morguard Investments Limited Owner: Rosemère Centre Properties Limited An Independent Style Southcentre Calgary, Alberta Management Company /Owner: Oxford Properties Group St. -

This License Agreement Made As of This

Abridged INFORMATION PAGE This page sets out information which is referred to and forms part of the TELECOMMUNICATIONS LICENSE AGREEMENT made as of the 1st day of November, 2004 between THE CADILLAC FAIRVIEW CORPORATION LIMITED as agent for the Owner(s) as the Licensor and BELL CANADA as the Licensee. The information is as follows: Building: The office building municipally known as 77 Metcalfe in the City of Ottawa, and the Province of Ontario. Floor Area of Deemed Area: 110 square feet. Commencement Date: the 1st day of November, 2004. License Fee: the annual sum of Two Thousand Two Hundred dollars ($2,200.00) calculated based on the annual rate of Twenty dollars ($20.00) per square foot of the floor area of the Deemed Area. The floor area of the Deemed Area is estimated to be 110 square feet. The exact measurement of the Deemed Area may be verified by an architect or surveyor employed by the Licensor for that purpose and upon verification, an adjustment of the License Fee and the floor area will be made retroactively to the Commencement Date. Notices: Licensor c/o The Cadillac Fairview Corporation Limited 20 Queen Street West, 5th Floor Toronto, Ontario M5H 3R4 Attention: Director of Technical Services Business Innovation and Technology Services Licensee Nexacor Realty Management Inc. 304 The West Mall Toronto, Ontario M9B 6E2 Attention: Director, Lease Administration Phone: With a copy to: Bell Canada 87 Ontario West Montreal, Quebec H2X 1Y8 Attention: General Manager, Asset Management Fax: Prime Rate Reference Bank: The Toronto Dominion Bank. Renewal Term(s): Three (3) period(s) of Five (5) years. -

Security Personnel Collective Agreement

SECURITY PERSONNEL COLLECTIVE AGREEMENT BETWEEN: THE CADILLAC FAIRVIEW CORPORATION LIMITED CF FAIRVIEW MALL (hereinafter called the "Company'') -and- UNIFOR and its Local 2003E (hereinafter called the "Union") March 1, 2017 to February 29,2020 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE NO. ARTICLE 1 PURPOSE OF AGREEMENT ................................................................................................. 4 ARTICLE 2 SCOPE AND RECOGNITION ............................................................................................... 4 ARTICLE 3 MANAGEMENT RIGHTS ................................................................................................... 4 ARTICLE 4 UNION SECURITY ............................... .............................................................................. 5 ARTICLE 5 NO STRIKES OR LOCKOUTS ............................................................................................. 6 ARTICLE 6 UNION REPRESENTATION ............................................................................................... 6 ARTICLE 7 DISCIPLINE AND DISCHARGE ............................................................................................ 8 ARTICLE 8 NO DISCRIMINATION ....................................................................................................... 8 ARTICLE 9 GRIEVANCE PROCEDURE ................................................................................................. 9 ARTICLE 10 ARBITRATION ................................................................................................................. -

Office Improvement Manual & Construction Guidelines Fire And

Office Improvement Manual & Construction Guidelines Fire and Life Safety Regulations December 2019 1 Table of Contents 2 INTRODUCTION 6 1.0 1 . 0 LANDLORD INFORMATION AND CONSULTANTS 7 1 . 1 Project Management Purpose 7 1 . 2 Cadillac Fairview Operations Contacts 8 1 . 3 Cadillac Fairview Security/Life Safety Contacts 9 1 . 4 Landlord’s Base Building Consultants 9 1 . 5 Hazardous Materials/Asbestos Related Work 11 2 . 0 TENANT IMPROVEMENT DOCUMENTATION 12 2 . 1 Drawings and Specifications 12 2 . 2 Floor Plans 12 2 . 3 Reflected Ceiling/Lighting Plans 12 2 . 4 Construction Details 12 Complete Mechanical, Sprinkler, Electrical, Building-Automation, Security System, Life-Safety System and Fire 2 . 5 13 Alarm Drawings 2 . 6 Structural Drawings 13 2 . 7 Hardware Schedule 13 2 . 8 Washroom Fixtures, Finishes and Accessories 13 3 . 0 PROJECT DOCUMENTS 14 3 . 1 Approved Drawings 14 3 . 2 Construction Schedule 14 3 . 3 Tenant Design Consultants 15 4 . 0 CONTRACTOR WORK REGULATIONS 16 4 . 1 Appointment of the Contractor 16 4 . 2 Insurance Certificates 16 4 . 3 Permits 16 4 . 4 Health and Safety Requirements 17 4 . 5 Workplace Safety and Insurance Board Clearance Certificate 17 4 . 6 Notice of Projects Form 17 4 . 7 List of Sub-Contractors 17 4 . 8 Deficiency Deposit 18 4 . 9 WHMIS Regulation 18 4 . 1 0 Hazardous Material Report 18 4 . 1 1 Emergency Contact 18 5 .0 SECURITY 19 5 .1 Occupied Areas 19 5 .2 Key Control 19 5 .3 Identification Badges 19 6 .0 SITE CONDITIONS 20 6 .1 Working Hours 20 6 .2 Noise disturbance – Sensitive work 20 6 .3 Construction Odors 20 6 .4 Temporary Services 20 6 .5 Work Site Protection 20 6 .6 Base Building Finishes 21 6 .7 First Aid Requirements 21 7 .0 SITE ACCESS REGULATIONS 22 7 .1 Shipping & Receiving 22 7 .2 Freight Elevator/Escalators 22 7 .3 Parking 23 7 .4 Recycling and Waste Removal 23 7 . -

Clients Count on David for Creative Solutions to the Challenges of Their Most Critical Transactions

Clients count on David for creative solutions to the challenges of their most critical transactions. David advises on complex commercial real estate deals, specializing in large and intricate sales, purchases, joint venture agreements, developments and financings. He also has significant experience in publicprivate partnerships for large infrastructure projects. David’s clients, including some of the world’s largest real estate developers, pension funds and investment funds, rely on him for his understanding of their businesses and his practical advice. His clientfocused approach has also David G. Reiner earned the trust of several Canadian banks, which regularly choose him for their Partner important matters. Office REPRESENTATIVE WORK Toronto Cadillac Fairview Corporation Limited Tel Acted for Cadillac Fairview and its affiliated entities in its joint venture with TD 416.367.7478 Greystone Asset Management relating to CF Carrefour Laval, the largest enclosed shopping centre in the Greater Montréal Area, including approximately Email 1,200,000 square feet of retail space. [email protected] Cadillac Fairview Corporation Limited Expertise Acted for Cadillac Fairview in its acquisition from First Gulf and its partners of Commercial Real Estate one of the largest planned commercial developments in Canada, the 38acre Corporate East Harbour project in downtown Toronto. Infrastructure The Blackstone Group Inc. Bar Admissions Acted for real estate funds managed by The Blackstone Group Inc. and their Ontario, 2008 affiliates in Blackstone's $6.2billion allcash acquisition of Dream Global Real Estate Investment Trust and the separation of its external asset manager, Dream Asset Management. Cadillac Fairview Corporation Limited Acted for Frontside Developments L.P., a joint venture between Cadillac Fairview and Investment Management Corporation of Ontario, in the sale of a 30% interest in the development site located at 160 Front Street West, Toronto, to The TorontoDominion Bank. -

Court File No. CV-20-00642013-00CL ONTARIO

Court File No. CV-20-00642013-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE (COMMERCIAL LIST) IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES’ CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-36, AS AMENDED AND IN THE MATTER OF A PLAN OF COMPROMISE OR ARRANGEMENT OF COMARK HOLDINGS INC., BOOTLEGGER CLOTHING INC., CLEO FASHIONS INC. AND RICKI’S FASHIONS INC. APPLICANTS SERVICE LIST (As at June 23, 2020) PARTY CONTACT OSLER, HOSKIN & HARCOURT LLP Tracy Sandler Box 50, 1 First Canadian Place Tel: 416.862.5890 100 King Street West, Suite 6200 Email: [email protected] Toronto, ON M5X 1B8 John MacDonald Fax: 416.862.6666 Tel: 416.862.5672 Email: [email protected] Counsel to the Applicants Karin Sachar Tel: 416.862.5949 Email: [email protected] Martino Calvaruso Tel: 416.862.6665 Email: [email protected] 7066861 [2] GOODMANS LLP Rob Chadwick Bay Adelaide Centre – West Tower Tel: 416.597.4285 333 Bay Street, Suite 3400 Email: [email protected] Toronto, Ontario M5H 2S7 Brendan O’Neill Fax: 416.979.1234 Tel: 416.849.6017 Email: [email protected] Counsel to the Court-Appointed Monitor Bradley Wiffen Tel: 416.597.4208 Email: [email protected] ALVAREZ & MARSAL CANADA INC. Doug McIntosh Royal Bank Plaza, South Tower, Suite 200 Tel: 416.847.5150 P.O. Box 22 Email: [email protected] Toronto, Ontario M5J 2J1 Alan J. Hutchens Fax: 416.847.5201 Tel: 416.847.5159 Email: [email protected] Court-Appointed Monitor Joshua Nevsky Tel: 416.847.5161 Email: [email protected] John-Luke Ip Tel: 416.847.5154 Email: [email protected] CHAITONS LLP Harvey Chaiton 5000 Yonge Street Tel: 416-218-1129 10th Floor Email: [email protected] Toronto, ON M2N 7E9 Fax: 416-218-1849 Counsel for Stern Partners Inc. -

Communication from Cadillac Fairview

CF Cadillac Fairview January 8, 2021 To the Members of the Infrastructure and Environment Committee Re: IE19.11 yongeTOmorrow - Municipal Class Environmental Assessment on Yonge Street. Staff Report and Recommendation before Infrastructure and Environment Committee - January 11, 2021. Cadillac Fairview, as owner and operator of CF Toronto Eaton Centre and on behalf of the businesses within it, is writing to again object in the strongest possible terms to the proposed reconfiguration of Yonge Street ("Recommended Design Concept 4D") - most especially the effective closure of the Street to vehicles. City staff's recommendation found within the above-referenced report wfll damage the community and vitality of business in this neighbourhood and have serious negative consequences both operationally and economically. In addition to our property generating hundreds of millions of dollars in sales taxes, CF Toronto Eaton Centre is one of the City of Toronto's largest taxpayers contributing approximately $80 million annually. Through our relentless reinvestment in the physical property and taxes, we have helped to bu ild a community that is vibrant and an attractive destination for tourists, students, employers, and major events and festivals. We have committed to invest our time, money, and energy in this neighbourhood in spite of rising commercial taxes, endemic social problems, and serious congestion that significantly impacts daytime delivery, adding to the already very challenging operating environment. We are aligned with members of our community and are eager to have an improved pedestrian experience and public realm; however, the pedestrian-only zones and bike lanes that are now part of the current preferred design concept would be especially damaging for CF Toronto Eaton Centre and local businesses. -

CANADIAN SHOPPING CENTRE STUDY 2019 Sponsored By

CANADIAN SHOPPING CENTRE STUDY 2019 Sponsored by DECEMBER 2019 RetailCouncil.org “ helps Suzy Shier drive traffic and sales!” Faiven T. | Marketing Coordinator | Suzy Shier Every retailer pays significantly for marketing opportunities through their leases. However, 90% of retailers never take advantage of the benefits of these investments. Every shopping center promotes their retailers’ marketing campaigns to millions of consumers to drive traffic and sales to their retailers. Engagement Agents helps retailers drive more traffic and sales, while saving money, time and resources by making it easy to take advantage of their al ready-paid-for marketing dollars! Learn more at www.EngagementAgents.com. Also, read our article on pag e 25 of this Study! Sean Snyder, President [email protected] www.EngagementAgents.com 1.416.577.7326 CANADIAN SHOPPING CENTRE STUDY 2019 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................1 2. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................3 3. T op 30 Shopping Centres in Canada by Sales Per Square Foot ...................................................................................................5 3a. Comparison: 2019 Canadian Shopping Centre Productivity Annual Sales per Square Foot vs. 2018 and 2017 ...............................................8 3b. Profile Updates on Canada’s -

Document.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Cadillac Fairview and YCC Introduction 2 YCC Building Hours 3 Cadillac Fairview Meet the Team 4 Security and Life Safety 5 Janitorial 7 Green Initiatives 7 Parking and Transportation 8 Available Services 10 Corporate Concierge Service 11 Amenities at YCC 12 Amenities in the Neighborhood 13 Restaurants 14 Emergency Preparedness 15 General Information, Fire Wardens/Deputy Wardens 16 Fire Alarm 18 Bomb Threat Procedures 20 Medical Emergencies 22 Elevator Malfunction/Entrapment 23 2 WELCOME TO YONGE CORPORATE CENTRE On behalf of Cadillac Fairview Corporation we are pleased to welcome you to Yonge Corporate Centre. YCC is one of North Toronto’s premier office towers whose employees are dedicated to your total satisfaction. We have prepared this guide to answer many of the most commonly asked questions regarding building operations, systems and the numerous amenities in and around YCC. We strongly encourage you and your staff to familiarize yourself with the services and operations of YCC and we hope you find this helpful and informative. Please retain this manual for future reference as it will be amended and updated time to time. Studies show that more than half of all adult waking hours are spent in work related activities. YCC is designed to be a pleasant and productive business home during these hours by providing a quality and efficient working environment for business’s and its employees. We are proud you have chosen the Yonge Corporate Centre and look forward to a long and mutually beneficial relationship. We welcome your comments and encourage you to discuss with us any suggestions as to how we may improve our services: The Cadillac Fairview Corporation Limited 4100 Yonge Street, Suite 412, Toronto, Ontario M2P 2B5 Phone: (416) 222-5100 Fax: (416) 222-8452 Daily Access Hours are 6:00 am - 7:00 pm, After Hours Access is 7:00 pm - 6:00 am THE CADILLAC FAIRVIEW CORPORATION Cadillac Fairview is one of North America’s largest investors, owners and managers of commercial real estate. -

Cadillac Fairview Corporation Limited for Markville Shopping Centre Located at 5000 Highway 7 East Retail Business Holidays Act Application for Exemption

Clause No. 1 in Report No. 7 of Committee of the Whole was adopted, without amendment, by the Council of The Regional Municipality of York at its meeting held on April 17, 2014. 1 CADILLAC FAIRVIEW CORPORATION LIMITED FOR MARKVILLE SHOPPING CENTRE LOCATED AT 5000 HIGHWAY 7 EAST RETAIL BUSINESS HOLIDAYS ACT APPLICATION FOR EXEMPTION Committee of the Whole held a public meeting on April 3, 2014, pursuant to the Retail Business Holidays Act, to consider a proposed bylaw to permit the Markville Shopping Centre located at 5000 Highway 7 East, City of Markham, to remain open on the holidays and during the hours set out in Recommendation 3, and recommends: 1. Receipt of the following deputations: 1. Liem Vu, General Manager, Promenade Shopping Centre, on behalf of Cadillac Fairview Corporation Limited for Markville Shopping Centre, who during the deputation withdrew the request for Markville Shopping Centre to remain open on Easter Sunday 2. Peter Thoma, Partner, urbanMetrics. 2. Receipt of the report dated March 19, 2014 from the Regional Solicitor and Executive Director, Corporate and Strategic Planning. 3. Permitting Cadillac Fairview Corporation Limited for its retail business Markville Shopping Centre located at 5000 Highway 7 East, City of Markham, to remain open on New Year’s Day, Family Day, Good Friday, Victoria Day, Canada Day, Labour Day and Thanksgiving Day between 11 a.m. and 6 p.m. pursuant to the Retail Business Holidays Act. 4. The Regional Solicitor prepare the necessary bylaw giving effect to the exemption. Clause No. 1, Report No. 7 2 Committee of the Whole April 3, 2014 1. -

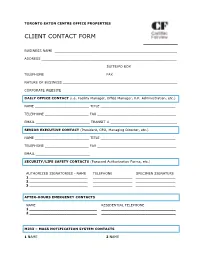

Client Contact Form

TORONTO EATON CENTRE OFFICE PROPERTIES CLIENT CONTACT FORM BUSINESS NAME ___________________________________________________________ ADDRESS _________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________ SUITE/PO BOX _____________________ TELEPHONE _____________________________ FAX ______________________________ NATURE OF BUSINESS _______________________________________________________ CORPORATE WEBSITE _______________________________________________________ DAILY OFFICE CONTACT (i.e. Facility Manager, Office Manager, V.P. Administration, etc.) NAME __________________________ TITLE ____________________________________ TELEPHONE _____________________ FAX ______________________________________ EMAIL __________________________ TRANSIT # ________________________________ SENIOR EXECUTIVE CONTACT (President, CEO, Managing Director, etc.) NAME __________________________ TITLE ____________________________________ TELEPHONE _____________________ FAX ______________________________________ EMAIL __________________________ SECURITY/LIFE SAFETY CONTACTS (Passcard Authorization Forms, etc.) AUTHORIZED SIGNATORIES - NAME TELEPHONE SPECIMEN SIGNATURE 1 _________________________ _________________ _________________ 2 _________________________ _________________ _________________ 3 _________________________ _________________ _________________ AFTER-HOURS EMERGENCY CONTACTS NAME RESIDENTIAL TELEPHONE 1 _____________________________ ________________________________ 2 _____________________________ ________________________________ -

Strategic Land Development Office

CITY OF HAMILTON PLANNING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT Economic Development Division TO: Mayor and Members General Issues Committee COMMITTEE DATE: January 15, 2020 SUBJECT/REPORT NO: Feasibility of Locating a New Arena on the Hamilton Mountain (PED20008) (City Wide) (Outstanding Business List item) WARD(S) AFFECTED: City Wide PREPARED BY: Ryan McHugh (905) 546-2424 Ext. 2725 SUBMITTED BY: Glen Norton Director, Economic Development Planning and Economic Development Department SIGNATURE: Discussion of Confidential Appendices “A”, “E” and “F” to report PED18168(b) in closed session is subject to the following requirement(s) of the City of Hamilton’s Procedural By-law and the Ontario Municipal Act, 2001: A position, plan, procedure, criteria or instruction to be applied to any negotiations carried on or to be carried on by or on behalf of the municipality or local board. RECOMMENDATION (a) That staff be directed to take no further action on the unsolicited proposal attached as confidential Appendix “A” to report PED20008. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY At Council’s request, Michael Andlauer, who is the owner of the Hamilton Bulldogs, appeared at the October 2, 2019 General Issues Committee (GIC) meeting and presented the new arena proposal attached as Appendix “B” to Report PED20008. This unsolicited proposal, which was submitted by Cadillac Fairview and Michael Andlauer, outlined a development plan which included a new 6,000 seat arena and an 1,800-car parking garage on Cadillac Fairview’s Lime Ridge Mall site that is located at 999 Upper Wentworth Street. The estimated cost that was provided for the 6,000-seat arena was $72 M ($12 K per seat) and the estimated cost of an 1,800-car parking garage provided was $52 M ($30 K per stall).