Attachment26.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Formal and Informal School Structures Support Gender

Helping Double Rainbows Shine: How Formal and Informal School Structures Support Gender Diverse Youth on the Autism Spectrum Shelley M. Barber A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2020 Reading Committee: Kristen Missall, Chair Felice Orlich Carly Roberts Ilene Schwartz Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Education ©Copyright 2020 Shelley M. Barber University of Washington Abstract Helping Double Rainbows Shine: How Formal and Informal School Structures Support Gender Diverse Youth on the Autism Spectrum Shelley M. Barber Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Kristen Missall School Psychology, College of Education Ten adolescents (14 through 19 years old) diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) who identify as transgender/gender diverse were interviewed to better understand their perceptions and interpretations of school experiences as part of a basic qualitative study. Participants were asked to reflect on what helped them feel safe and supported in terms of their gender identity at school, what led them to feel unsafe and unsupported, and what they thought could be put in place to better support their gender identities. Table of Contents Acknowledgments............................................................................................................ i Chapter 1: Introduction .................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 2: Literature Review ........................................................................................ -

P. Diddy with Usher I Need a Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will

P Diddy Bad Boys For Life P Diddy feat Ginuwine I Need A Girl (Part 2) P. Diddy with Usher I Need A Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will Find A Way Paladins Going Down To Big Mary's Palmer Rissi No Air Paloma Faith Only Love Can Hurt Like This Pam Tillis After A Kiss Pam Tillis All The Good Ones Are Gone Pam Tillis Betty's Got A Bass Boat Pam Tillis Blue Rose Is Pam Tillis Cleopatra, Queen Of Denial Pam Tillis Don't Tell Me What To Do Pam Tillis Every Time Pam Tillis I Said A Prayer For You Pam Tillis I Was Blown Away Pam Tillis In Between Dances Pam Tillis Land Of The Living, The Pam Tillis Let That Pony Run Pam Tillis Maybe It Was Memphis Pam Tillis Mi Vida Loca Pam Tillis One Of Those Things Pam Tillis Please Pam Tillis River And The Highway, The Pam Tillis Shake The Sugar Tree Panic at the Disco High Hopes Panic at the Disco Say Amen Panic at the Disco Victorious Panic At The Disco Into The Unknown Panic! At The Disco Lying Is The Most Fun A Girl Can Have Panic! At The Disco Ready To Go Pantera Cemetery Gates Pantera Cowboys From Hell Pantera I'm Broken Pantera This Love Pantera Walk Paolo Nutini Jenny Don't Be Hasty Paolo Nutini Last Request Paolo Nutini New Shoes Paolo Nutini These Streets Papa Roach Broken Home Papa Roach Last Resort Papa Roach Scars Papa Roach She Loves Me Not Paper Kites Bloom Paper Lace Night Chicago Died, The Paramore Ain't It Fun Paramore Crush Crush Crush Paramore Misery Business Paramore Still Into You Paramore The Only Exception Paris Hilton Stars Are Bliind Paris Sisters I Love How You Love Me Parody (Doo Wop) That -

Quartet March2020

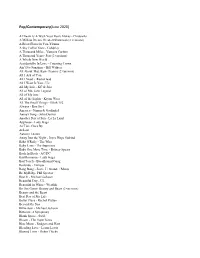

Pop/Contemporary (June 2020) A Dream Is A Wish Your Heart Makes - Cinderella A Million Dream Greatest Showman (2 versions) A River Flows in You-Yiruma A Sky Full of Stars - Coldplay A Thousand Miles - Vanessa Carlton A Thousand Years- Peri (2 versions) A Whole New World Accidentally In Love - Counting Crows Ain't No Sunshine - Bill Withers All About That Bass- Trainor (2 versions) All I Ask of You All I Need - RadioHead All I Want Is You - U2 All My Life - KC & Jojo All of Me- John Legend All of My love All of the Lights - Kayne West All The Small Things - Blink 182 Always - Bon Jovi America - Simon & Garfunkel Annie's Song - John Denver Another Day of Sun - La La Land Applause - Lady Gaga As Time Goes By At Last Autumn Leaves Away Into the Night - Joyce Hope Siskind Baba O'Reily - The Who Baby Love - The Supremes Baby One More Time - Britney Spears Back In Black - AC/DC Bad Romance - Lady Gaga Bad Touch - Bloodhound Gang Bailando - Enrique Bang Bang - Jessie J / Grande / Minaj Be MyBaby- Phil Spector Beat It - Michael Jackson Beautiful Day - U2 Beautiful in White - Westlife Be Our Guest- Beauty and Beast (2 versions) Beauty and the Beast Best Day of My Life Better Place - Rachel Platten Beyond the Sea Billie Jean - Michael Jackson Bittersweet Symphony Blank Space - Swift Bloom - The Paper Kites Blue Moon - Rodgers and Hart Bleeding Love - Leona Lewis Blurred Lines - Robin Thicke Bohemian Rapsody-Queen Book of Days - Enya Book of Love - Peter Gabriel Boom Clap - Charli XCX Brown Eyed Girl - Van Morrison Budapest - Geo Ezra Buddy Holly- -

Crowning the Queen of the Sonoran Desert: Tucson and Saguaro National Park

Crowning the Queen of the Sonoran Desert: Tucson and Saguaro National Park An Administrative History Marcus Burtner University of Arizona 2011 Figure 1. Copper Pamphlet produced by Tucson Chamber of Commerce, SAGU257, Box 1, Folder 11, WACC. “In a canon near the deserted mission of Cocospera, Cereus giganteus was first met with. The first specimen brought the whole party to a halt. Standing alone upon a rocky projection, it rose in a single unbranched column to the height of some thirty feet, and formed a sight which seemed almost worth the journey to behold. Advancing into the canon, specimens became more numerous, until at length the whole vegetation was, in places, made up of this and other Cacaceae. Description can convey no adequate idea of this singular vegetation, at once so grand and dreary. The Opuntia arborescens and Cereus Thurberi, which had before been regarded with wonder, now seemed insignificant in comparison with the giant Cactus which towered far above.” George Thurber, 1855, Boundary Commission Report.1 Table of Contents 1 Asa Gray, ―Plantae Novae Thurberianae: The Characters of Some New Genera and Species of Plants in a Collection Made by George Thurber, Esq., of the Late Mexican Boundary ii List of Illustrations v List of Maps ix Introduction Crowning the Queen of the Desert 1 The Question of Social Value and Intrinsically Valuable Landscapes Two Districts with a Shared History Chapter 1 Uncertain Pathways to a Saguaro National Monument, 1912-1933 9 Saguaros and the Sonoran Desert A Forest of Saguaros Discovering -

Encoding and Decoding of Resistant Ideology in Music Video Desiree Damon Trinity University

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Communication Honors Theses Communication Department 5-4-2005 The Last Day on Earth: Encoding and Decoding of Resistant Ideology in Music Video Desiree Damon Trinity University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/comm_honors Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons Recommended Citation Damon, Desiree, "The Last Day on Earth: Encoding and Decoding of Resistant Ideology in Music Video" (2005). Communication Honors Theses. 1. http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/comm_honors/1 This Thesis open access is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Damon 1 The Last Day on Earth: Encoding and Decoding of Resistant Ideology in Music Video By Desirée Damon A Department Honors Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication at Trinity University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with departmental honors. April 11, 2005 ____________________________ _____________________________ THESIS ADVISOR DEPARTMENT CHAIR ____________________________ THESIS ADVISOR ASSOCIATE VICE PRESIDENT FOR ACADEMIC AFFAIRS, CURRICULUM AND STUDENT ISSUES “This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License. To view a copy of this license, visit <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/> or send a letter to Creative Commons, 559 Nathan Abbott Way, Stanford, California 94305, USA.” Damon 2 ABSTRACT According to Stuart Hall’s theory of encoding and decoding, an audience member, based on their individual ideological perspectives, can read media texts in one of three ways: dominant, negotiated, or resistant. -

Craig Interagency Dispatch Center

Craig Interagency Dispatch Center Field Operations Guide 2021 This guide is intended to familiarize you with our local organizations and operating procedures. Please keep it handy and review it frequently. General In-briefing and Debriefing Checklists pg. 2 Organizations and Cooperators pg. 4 Area & Zone Maps pg. 11 Dispatch Operations pg. 16 Expectations pg. 17 Initial Attack Operations and Protocol pg. 18 FireCode Chart pg. 26 Logistics and Administration pg. 27 Implementation of Federal Wildland Fire Policy-Response to Wildland Fire /FMP pg. 28 Fire Management Units pg. 29 Run Cards pg. 31 USFS/NPS Routt National Forest Operations pg. 45 Dinosaur National Monument Fire Operations pg. 51 Fire Behavior and Tactics Weather pg. 53 Fuels pg. 54 Critical Fuel Moistures pg. 58 Pocket Cards pg. 59 Oil and Gas Field Safety pg. 61 Wildland Fire Risk and Hazard Assessment pg. 65 Aviation pg. 69 Communications pg. 81 IA Aircraft Communications Zone Map pg. 90 Incident Management Teams (IMT’s) pg. 91 Emergency Procedures pg. 95 1 IN-BRIEFING CHECKLIST From Dispatch _____ Copy of current weather forecast _____ Current & expected activity (if Zone FMO not available) _____ Size-up cards _____ Area map packets (please return at end of assignment) _____ NWDFA visitor briefing (Field Operations Guide) _____ Logistics To Dispatch _____ Manifest, phone numbers and radio call sign provided to dispatch _____ Hotel or cell number provided to dispatch for after-hours dispatches _____ Copy of contracts from contract resources _____ Copy of Redcards (give copy to AFMO) From Zone FMO’s _____ Current & expected fire situation _____ Oil & gas briefing _____ Unexploded ordnance (UXO) briefing _____ Fuels & tactics briefing including Fire Management Plan, appropriate response and fire restrictions _____ Radios programmed _____ Timesheet and equipment shift tickets initiated with proper charge codes e.g. -

Paramore Free Mp3 Download Paramore Free Mp3 Download

paramore free mp3 download Paramore free mp3 download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67d2d15b9c118498 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Free Mp3 Downloads. Paramore – Ignorance mp3 music downloads. Mp3 » P » Paramore – Ignorance. Download Paramore – Ignorance Mp3 Music. Note: To download, Left click or Right click and "Save Target As" How to Download Free Music Watch Ignorance Music Video Music Videos: Paramore Music Videos Artist: Paramore Mp3 Download Downloaded: Times Zip Password: None File Size (MB): N/A Find lyrics: N/A You are Downloading : Paramore – Ignorance MP3. Free Paramore – Ignorance Ringtone. Download Kumpulan Lagu Paramore Mp3 Full Album Lengkap. Kumpulan Lagu Paramore Mp3 Full Album di jurangmusic woke guys jumpa lagi dengan admin yang kali ini akan membagikan kepada kalian semua Lagu Mp3 Paramore yang merupakan Grup Band Rock yang sangat terkenal dan Populer di Dunia Musik ini. Kumpulan Lagu Paramore ini sangatlah banyak penikmatnya dengan lagu Lagu Terbaru nya ataupun Lagu Lama dari Paramore. -

The Honey Badgers - Wedding Cover Songs (Vocal) - 2020

The Honey Badgers - Wedding Cover Songs (Vocal) - 2020 Artist Song Adele Hello AJR 100 Bad Days AJR Sober Up Alison Krauss When You Say Nothing At All Amos Lee Sweet Pea Band of Horses No One’s Gonna Love You Bastille Pompeii Blake Shelton Honey Bee Bob Dylan Don't Think Twice It's Alright Bob Dylan I Shall Be Released Bob Dylan The Times They are A-Changing Bob Dylan / Adele Make You Feel My Love Bon Iver Skinny Love Bright Eyes First Day of My Life Bright Eyes Lua Bruno Mars Marry You Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey Christina Perri A Thousand Years Creedence Clearwater Revival Bad Moon Rising Crosby Stills & Nash Helplessly Hoping Dallas Green Beautiful Girl Dave Barnes I Have and I Always Will David Mayfield Breath of Love Death Cab for Cutie I Will Follow You Into the Dark Death Cab for Cutie Stay Young, Go Dancing Dixie Chicks Cowboy Take Me Away Dolly Parton Jolene Ed Sheeran Shape of You Ed Sheeran Perfect Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud Edward Sharpe Home Elvis Presley Can't Help Falling In Love Elvis Presley Love Me Tender First Aid Kit Emmylou Fleetwood Mac Rhiannon Fleetwood Mac Landslide Fleetwood Mac Dreams Fleetwood Mac Songbird Florence & The Machine Shake it Out Florence & The Machine Dog Days Are Over Grateful Dead Friend of the Devil Green Day Time of Your Life Hall & Oates You Make My Dreams Henry Mancini Moon River Howie Day Collide Imagine Dragons Radioactive Imagine Dragons Believer Imagine Dragons Demons honeybadgerfolk.com 1 The Honey Badgers - Wedding Cover Songs (Vocal) - 2020 Artist Song Ingrid Michaelson You -

Paramore the Only Exception Sheet Music

Paramore The Only Exception Sheet Music Download paramore the only exception sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 2 pages partial preview of paramore the only exception sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 1695 times and last read at 2021-09-26 13:20:45. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of paramore the only exception you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Flute, Ukulele Ensemble: Musical Ensemble Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music The Only Exception The Only Exception sheet music has been read 1882 times. The only exception arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 15:38:03. [ Read More ] The Only Exception String Quartet The Only Exception String Quartet sheet music has been read 2971 times. The only exception string quartet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-23 18:30:23. [ Read More ] Paramore For A Pessimist I M Pretty Optimistic Drum Sheet Music Paramore For A Pessimist I M Pretty Optimistic Drum Sheet Music sheet music has been read 3862 times. Paramore for a pessimist i m pretty optimistic drum sheet music arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-26 10:53:49. [ Read More ] Paramore Let The Flames Begin Drum Sheet Music Paramore Let The Flames Begin Drum Sheet Music sheet music has been read 8394 times. -

000026828.Pdf

paramore.net © 2009 Atlantic Recording Corporation for the United States and WEA International Inc. for fueledbyramen.com the world outside of the United States. All Rights Reserved. Printed in U.S.A. 075678958045 Hayley would like to thank: “Therefore I am well content with weaknesses, with insults, with distresses, with persecutions, with difficulties for Christ’s sake; for when I am weak, then I am strong.” Corinthians 10:12. Thank you God for being everywhere and in everything. Mom and Dad for being there for me over the past 2 years when I had a lot of growing up to do. Granny and Grandat, Nana, Erica- younger sisters aren’t supposed to be cooler than their older sisters. McKayla- you can read now! You’re a princess! Chadball for being a superhero, making me laugh really hard and just for loving me. Hannah HXC- roomies 4 life! The residents and former residents of The Gingerbread House. i settled down Sarah O. Bekah RUSSOM!!! Embi and the Ferro family. Sakura Sushi. Jackie and Steve Mallonee and everyone else I love in Kentucky! Toby, Moon, and Maximum Morse. Steve a twisted up frown disguised as a smile Looker (you made it). MY friend Eric Scandaolous- emphasis on the word “my”. Nathan and Liz James. Mitts for catching me when I fainted that one time. Punk and Amy. Jen well you would’ve never known Johnson for my pretty clothes! Brian O’Connor- you made me, haha. Dianne Edmondson. AJAX! Zach Jay for getting us lost in Tampa. Roger Nichols. My pastor- Jamie George. -

THE STATE of the WORLD's GIRLS 2015: the Unfinished Business Of

Because I am a Girl THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S GIRLS 2015 The Unfinished Business of Girls’ Rights 1 Because I am a Girl THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S GIRLS 2015 The Unfinished Business of Girls’ Rights S TURE IC P S ANO P Patna, Bihar, India. SPAULL/ JON 2 THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S GIRLS 3 Acknowledgements This report was made possible with the contributions and advice of many people and organisations. With special thanks to all those who wrote articles, poems and stories for the 2015 report: Sally Armstrong Chernor Bah President Jimmy Carter Imtiaz Dharker Julia Gillard Anita Haidary Joanne Harris Liya Kebede Graça Machel Katrine Marçal Catalina Ruiz Navarro Indra Nooyi Mariane Pearl Nawal El Sadaawi Bukky Shonibare S TURE IC P Girls Report Editorial Board: S ANO Sarah Hendriks – Chair, Director of Gender Equality and Social Inclusion, Plan International P Sharon Goulds – Editor and Project Manager of the Girls’ Report series Adam Short – Head of Advocacy, Plan International Jacqui Gallinetti – Director of Research and Knowledge Management, Plan International MILTON/ IANNE L Lucero Quiroga – Gender Advisor, consultant for Plan International Protesters in Brazil. Executive Group: Nigel Chapman CEO, Plan International Girls Report team: Rosemary McCarney CEO, Plan International Canada Sharon Goulds – editor, project manager and author Tanya Baron CEO, Plan International UK Jean Casey – research manager Lili Harris – project coordinator & researcher Reference Group – Plan International: Rosanna Viterri, Kanwal Ahluwalia, Alex Munive, Tanya Cox, Rashid Javed, Kristy Payne, Sarah Hendriks – director of gender equality and social inclusion, chair of editorial board and author Carla Jones, Sara Osterlund, Elena Ahmed, Stephanie Conrad and Keshet Dovrat. -

To Search This List, Hit CTRL+F to "Find" Any Song Or Artist Song Artist

To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Song Artist Length Peaches & Cream 112 3:13 U Already Know 112 3:18 All Mixed Up 311 3:00 Amber 311 3:27 Come Original 311 3:43 Love Song 311 3:29 Work 1,2,3 3:39 Dinosaurs 16bit 5:00 No Lie Featuring Drake 2 Chainz 3:58 2 Live Blues 2 Live Crew 5:15 Bad A.. B...h 2 Live Crew 4:04 Break It on Down 2 Live Crew 4:00 C'mon Babe 2 Live Crew 4:44 Coolin' 2 Live Crew 5:03 D.K. Almighty 2 Live Crew 4:53 Dirty Nursery Rhymes 2 Live Crew 3:08 Fraternity Record 2 Live Crew 4:47 Get Loose Now 2 Live Crew 4:36 Hoochie Mama 2 Live Crew 3:01 If You Believe in Having Sex 2 Live Crew 3:52 Me So Horny 2 Live Crew 4:36 Mega Mixx III 2 Live Crew 5:45 My Seven Bizzos 2 Live Crew 4:19 Put Her in the Buck 2 Live Crew 3:57 Reggae Joint 2 Live Crew 4:14 The F--k Shop 2 Live Crew 3:25 Tootsie Roll 2 Live Crew 4:16 Get Ready For This 2 Unlimited 3:43 Smooth Criminal 2CELLOS (Sulic & Hauser) 4:06 Baby Don't Cry 2Pac 4:22 California Love 2Pac 4:01 Changes 2Pac 4:29 Dear Mama 2Pac 4:40 I Ain't Mad At Cha 2Pac 4:54 Life Goes On 2Pac 5:03 Thug Passion 2Pac 5:08 Troublesome '96 2Pac 4:37 Until The End Of Time 2Pac 4:27 To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Ghetto Gospel 2Pac Feat.