SUMMARY Information FMS MARIST NOTEBOOKS Number 22 – Year XVII – December 2005 • Articles That Have Appeared Editor-In-Chief: in the Marist Notebooks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Champagnat Journal Contribute to Our Seeking; to As Well As How We Respond to Those Around Us

OCTOBER 2015 Vocation Engagement Spirituality AN INTERNATIONAL MARIST JOURNAL OF CHARISM IN EDUCATION volume 17 | number 03 | 2015 Inside: • Standing on the Side of Mercy • Marist Icons: essential to our Life and Mission Champagnat: An International Marist Journal of Charism in Education aims to assist its readers to integrate charism into education in a way that gives great life and hope. Marists provide one example of this mission. Editor Champagnat: An International Marist Journal of Tony Paterson FMS Charism in Education, ISSN 1448-9821, is [email protected] published three times a year by Marist Publishing Mobile: 0409 538 433 Peer-Review: Management Committee The papers published in this journal are peer- reviewed by the Management Committee or their Michael Green FMS delegates. Lee McKenzie Tony Paterson FMS (Chair) Correspondence: Roger Vallance FMS Br Tony Paterson, FMS Marist Centre, Peer-Reviewers PO Box 1247, The papers published in this journal are peer- MASCOT, NSW, 1460 reviewed by the Management Committee or their Australia delegates. The peer-reviewers for this edition were: Email: [email protected] Michael McManus FMS Views expressed in the articles are those of the respective authors and not necessarily those of Tony Paterson FMS the editors, editorial board members or the Kath Richter publisher. Roger Vallance FMS Unsolicited manuscripts may be submitted and if not accepted will be returned only if accompanied by a self-addressed envelope. Requests for permission to reprint material from the journal should be sent by email to – The Editor: [email protected] 2 | ChAMPAGNAT OCTOBER 2015 Champagnat An International Marist Journal of Charism in Education Volume 17 Number 03 October 2015 1. -

Constitutions and Statutes CONSTITUTIONS and STATUTES CONSTITUTIONS Institute of the Marist Brothers ISBN 979-12-80249-01-2

Constitutions and Statutes CONSTITUTIONS AND STATUTES CONSTITUTIONS Institute of the Marist Brothers ISBN 979-12-80249-01-2 9 791280 249012 Cover_EN_Costitu.indd 1 08/06/21 16:24 COSTITUZIONE_EN_DEF.indd 1 31/05/21 09:15 COSTITUZIONE_EN_DEF.indd 2 31/05/21 09:15 Constitutions and Statutes Institute of the Marist Brothers COSTITUZIONE_EN_DEF.indd 3 31/05/21 09:15 Institute of the Marist Brothers © Casa Generalizia dei Fratelli Maristi delle Scuole P.le Marcellino Champagnat, 2 00144 Rome – Italy [email protected] www.champagnat.org Production: Communications Department of General Administration June 2021 Constitutions and Statutes of the Marist Brothers / Institute of the Marist Brothers. C758 – Rome : Casa Generalizia dei Fratelli Maristi delle Scuole Fratelli Maristi, 2021. 2021 224 p. ; 19 cm ISBN 979-12-80249-01-2 1. Marist Brothers - Statutes. 2. Constitutions. 3. Missionaries – Vocation. CDD. 20. ed. – 271 Sônia Maria Magalhães da Silva - CRB-9/1191 Sistema Integrado de Bibliotecas – SIBI/PUCPR COSTITUZIONE_EN_DEF.indd 4 31/05/21 09:15 FOREWORD 7 APPROVAL DECREE OF 2020 11 CHAPTER I OUR RELIGIOUS INSTITUTE of BROTHERS IDENTITY OF THE MARIST BROTHER IN THE CHURCH 15 CHAPTER II OUR IDENTITY AS RELIGIOUS BROTHERS Institute of the Marist Brothers CONSECRATION AS BROTHERS 25 © Casa Generalizia dei Fratelli Maristi delle Scuole P.le Marcellino Champagnat, 2 A) EVANGELICAL COUNSEL OF CHASTITY 28 00144 Rome – Italy B) EVANGELICAL COUNSEL OF OBEDIENCE 32 [email protected] C) EVANGELICAL COUNSEL OF POVERTY 35 www.champagnat.org Production: Communications Department of General Administration June 2021 CHAPTER III OUR LIFE AS BROTHERS LIFE IN THE INSTITUTE 43 A) FRATERNAL LIFE IN COMMUNITY 44 B) CULTIVATING SPIRITUALITY 53 C) SENT ON MISSION 61 Constitutions and Statutes of the Marist Brothers / Institute of the Marist Brothers. -

U.S. Catholic Mission Handbook 2006

U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION HANDBOOK 2006 Mission Inventory 2004 – 2005 Tables, Charts and Graphs Resources Published by the U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION ASSOCIATION 3029 Fourth St., NE Washington, DC 20017-1102 Phone: 202 – 884 – 9764 Fax: 202 – 884 – 9776 E-Mail: [email protected] Web sites: www.uscatholicmission.org and www.mission-education.org U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION HANDBOOK 2006 Mission Inventory 2004 – 2005 Tables, Charts and Graphs Resources ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Published by the U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION ASSOCIATION 3029 Fourth St., NE Washington, DC 20017-1102 Phone: 202 – 884 – 9764 Fax: 202 – 884 – 9776 E-Mail: [email protected] Web sites: www.uscatholicmission.org and www.mission-education.org Additional copies may be ordered from USCMA. USCMA 3029 Fourth Street., NE Washington, DC 20017-1102 Phone: 202-884-9764 Fax: 202-884-9776 E-Mail: [email protected] Web Sites: www.uscatholicmission.org and www.mission-education.org COST: $4.00 per copy domestic $6.00 per copy overseas All payments should be prepaid in U.S. dollars. Copyright © 2006 by the United States Catholic Mission Association, 3029 Fourth St, NE, Washington, DC 20017-1102. 202-884-9764. [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: THE UNITED STATES CATHOLIC MISSION ASSOCIATION (USCMA)Purpose, Goals, Activities .................................................................................iv Board of Directors, USCMA Staff................................................................................................... v Past Presidents, Past Executive Directors, History ..........................................................................vi Part II: The U.S. -

A Book of Texts for the Study of Marist Spirituality

edwin l. keel, s.m. a book of texts for the study of marist spirituality 2 a book of texts for the study of marist spirituality compiled by edwin l. keel, s.m. ROME CENTER FOR MARIST STUDIES 1993 3 The call of Colin is to an adventure. John Jago, S.M., Mary Mother of our Hope 4 Introduction This book is an offshoot of the courses in Marist Spirituality that I have been offering since 1986 at the Center for Marist Studies in Rome and the Marist House in Framingham, and in 1992 at St. Anne’s Presbytery in London. In 1991 I decided that the mélange of photocopied English translations of texts that I was using then needed to be expanded. I also wished to make the texts available in their original languages. These will be found in the French edition. Because the book is structured around the three symbolic moments of Fourvière, Cerdon and Bugey, which the Constitutions of 1988 offer as the framework both for Marist formation and for the whole of Marist life, the book should be of use not only for Marist renewal programs, but for those involved in Marist initial formation and for any Marist who seeks a deeper grasp of Marist spirituality through a thematic study of texts significant in our spiritual tradition. The texts are collected and presented here with little or no commentary. It is for the reader to meet Colin and the other founders and early Marists in their own words, and to let those words open up new paths of insight, of feeling and of action. -

The Marists in Aleppo 1904 - …

The Marists in Aleppo 1904 - …... The beginnings In August 1904, four Marist Brothers arrived in Aleppo to run the school for Armenian Catholics in Telal Street. Later, they worked with the Greek Catholics by running the school of Saint Nicholas and with the Jesuits in their school in the old city. In 1932, they built their own school, Champagnat College, in Fayçal Street (currently called Georges Salem School). In 1948 they moved to the section of the city called Mohafzat. Since 1967, when the college was nationalised, they have worked with the Amal School. Their presence has been in the areas of the scouts, catechesis, the accompaniment of young people and in solidarity with the poor. In August 2004, the centenary of the presence of the Marist Brothers in Aleppo is being celebrated. The group Champagnat-Brothers has educated hundreds of young people in the Marist spirit through scouting since 1976 until today. The group Champagnat-Jabal (referring to the neighbourhood of Jabal el Saydé) was started first. Some young people, feeling the urgency of a Marist scouting education in the poorer neighbourhoods, dared to start a group for the children of this neighbourhood. Brothers and young people are continuing with this project in a spirit of enthusiasm and hope. P r o m i s e Beginning of the year C h r I s t m a s P a R t y End of the year Ceremony Champagnat Marist Family Movement Several lay people have participated in Marist formation sessions in Europe. On their return, they invited couples to form the “Champagnat Marist Family Movement”. -

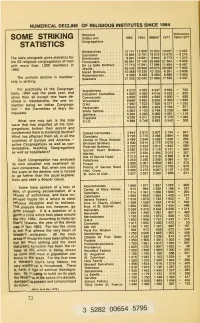

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

2015 Religious Formation Conference Member Congregations

2015 Religious Formation Conference Member Congregations ASC Adorers of the Blood of Christ OSB Benedictine Sisters of Erie PA OSB Benedictine Sisters of Pontifical Jurisdiction OSB Benedictine Srs of the Sacred Heart OSB Benedictine Srs of Virginia OSB Benedictine Women of Madison OSB Benet Hill Monastery OSF Bernardine Franciscan Sisters FIC Brothers of Christian Instruction SC Brothers of the Sacred Heart - New Orleans FdCC Canossian Daughters of Charity OCD Carmelite Srs of Baltimore CSV Clerics of St Viator CBS Congregation of Bon Secours CFC Congregation of Christian Brothers (Edmund Rice) CDP Congregation of Divine Providence -San Antonio CND Congregation of Notre Dame - Bedford NS CND Congregation of Notre Dame - Wilton, CT RC Congregation of Our Lady of the Cenacle (Religious of the Cenacle) OP Congregation of St Catherine of Siena (Racine Dominicans) CSJ Congregation of St Joseph CSSp Congregation of the Holy Spirit CHM Congregation of the Humility of Mary IWBS Congregation of the Incarnate Word & Blessed Sacrament CSsR Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer (Redemptorists) OP Congregation of the Most Holy Rosary (Adrian Dominicans) RJM Congregation of the Religious of Jesus and Mary CCVI Congregation of the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word CDP Congregation of the Sisters of Divine Providence CSJ Congregation of the Sisters of St Joseph - Brentwood CSJ Congregation of the Sisters of St Joseph of Boston PBVM Congregation of the Sisters of the Presentation OSF Congregation of the Sisters of the Third Order of St Francis OSF Congregation of the Third Order of St Francis - Joliet MC Consolata Missionary Sisters (Religious Teachers Filippini) DC Daughters of Charity of St. -

Pope Francis CONTENTS

2021 ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT To be saints is not a privilege for the few. But a vocation for everyone - Pope Francis CONTENTS STORIES Teaching as a Vocation Frank Chiment ................................................ p4 Our Aussie Bride of Christ Debbie Cramsie .............................................. p8 The Vocation to everyday heroism in the midst of Family Life Steve Buhagiar .............................................. p12 World Day of Grandparents & the Elderly RELIGIOUS LIFE Marilyn Rodrigues ........................................ p16 The Year on Family Love Catholic News Service ................................... p18 ORGANISATIONS Divine Word Missionaries ............................... p5 Marist Brothers Province of Australia............. p6 Catholic Institute of Sydney ............................ p6 Franciscan Friars Order of Friars Minor .......... p7 Dominican Sisters of St Cecilia ........................ p7 Vocation Centre ............................................ p10 Missonaries of the Sacred Heart .................. p14 PARENTING TEACHING FAMILY CATHOLIC VOCATIONS 2021 Publisher: The Catholic Weekly, 22 August 2021 Editorial contributors: Frank Chiment, Marilyn Rodrigues, Debbie Cramsie, Steven Buhagiar Design: Digital and Design Team | Cover image: Patrick J Lee Sales and Marketing: Steve Richards | www.catholicweekly.com.au 2 • CATHOLIC VOCATIONS 2021 Women sensing the call to religious life have a range of options they may not be aware of. CW With more than 50 congregations for women offering everything from a traditional monastic way of life to being more involved in the apostolic work of their communities, there is plenty of choice available right here in our backyard in Australia. FULL STORY www.catholicweekly.com.au PHOTO: Sr Mary Catherine, Dominican and Sr Mary Rose Discalced Carmelite A real Sister Act CATHOLIC VOCATIONS 2021 • 3 Teaching as a Vocation Teachers play a unique role in the lives of our youth. This has made me reflect upon the notion of“Teaching as a Vocation” within a Catholic school context. -

English: Brother Ross Murrin Trying to Understand History

Year XXI - n° 36 - September 2007 Year XXI - n° 36 - September 2007 index Editor-in-Chief: Brother AMEstaún The first beatified Marist Brothers. Publications Commission: Brothers Emili Turú, AMEstaún, Onori- Br. AMEstaún no Rota y Luiz Da Rosa. Translators Coordination: Brother Carlos Martín Hinojar page 2 Translators: Spanish: Brother Carlos Martín Hinojar Letter to my Brothers. Br. Seán Sammon French: Brother Giovanni Bigotto Brother Louis Richard Brother Jean Rousson Brother Fabricio Galiana page 5 English: Brother Ross Murrin Trying to understand history. Feliciano Montero García Portuguese: Brother Manoel Soares P. Eduardo Campagnani Brother Aloisio Khun page 10 Photography: AMEstaún, Archives de la Vicepostuladuría de España en San- The martyr is the one who does not save tan María de Bellpuig de Les Avellanes, his life at any price. José Sedano Gutiérrez Juan María Laboa Gallego Formatting and Photolithography: TIPOCROM, s.r.l. Via A. Meucci 28, 00012 Guidonia, Roma (Italia) page 18 Production and Administrative Cen- ter: La presencia marista en España Piazzale Marcellino Champagnat, 2 en vísperas de la guerra civil. C.P. 10250 - 00144 ROMA Br. Juan Moral Barrio Tel. (39) 06 54 51 71 Fax (39) 06 54 517 217 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.champagnat.org page 23 Publisher: Instituto dei Fratelli Maristi BR. BERNARDO Casa generalizia - Roma Diocese of Girona Printing: C.S.C. GRAFICA, s.r.l. Via A. Meucci 28, 00012 Guidonia, Roma (Italia) page 25 BR. LAURENTINO Diocese of Burgos page 33 BR. VIRGILIO Diocese of Pamplona page 39 DIOCESE -

The Marist Brothers SPRING 2016

The Marist TODAY’S Brothers SPRING 2016 n July 23, 1816, the day after their promise ordination, an enthusiastic group of fidelity in young priests including Marcellin the bosom Champagnat travel to the shrine of Fourvière of our holy in Lyon, France. At the feet of the Black mother A Lumen Award- Madonna, they promised to establish the the Roman winning publication Society of Mary. In 2016, we will celebrate Catholic Church, cleaving with all our strength of the Province of the pledge made in that chapel 200 years to its supreme head the Roman Pontiff and to the United States ago: our most reverend bishop, the ordinary, that of America “All for the greater we may be good ministers of Jesus Christ, glory of God and the nourished by the words of faith and by the greater honour of wholesome teaching which by his grace we Mary, Mother of the have received. Lord Jesus. We the We trust that under the reign of our most undersigned, striving Christian king, the friend of peace and religion, to work together for this institute will shortly come to light and we the greater glory of solemnly promise that we shall spend ourselves God and the honour and all we have in saving souls in every way of Mary, Mother under the very august name of the Virgin of the Lord Jesus, Mary and with her help. And may the holy and assert and declare immaculate conception of the Blessed Virgin our sincere intention Mary be praised. Amen.” and firm will of consecrating ourselves at the first opportunity to founding the pious From the beginning, the first Marists congregation of Mary-ists. -

Marist Brothers Celebrate 200 Years

THE SENTINEL Marist High School Volume 53, Issue 1 4200 west 115th street, chicago, il 60655 SEPTEMBER 30, 2016 Marist Brothers celebrate 200 years “Marcellin used the skills that his father by Faith Laughran had taught him to build the furniture,” editor-in-chief Marist president Brother Hank Hammer said. “The image from that period that This school year marks the anniversary survives to this day is of that table. It is an of the beginning of the Marist Brothers. important symbol.” 200 years ago, Marcellin Champagnat Champagnat taught his first two students began his mission to educate and restore at this table, Jean-Marie Granjon and Jean people’s faith, starting in France. Baptiste Audras, who did not know how to On July 22, 1816, a young Marcellin read or write. Champagnat was ordained a priest, and he The table began to become an image, committed himself to a life of service. He like the Eucharistic table at mass, feeding hoped to bring the teachings and examples the two recruits with knowledge so they of Christ and Mary to the people of France, would have the strength to go out and who were recovering from the recent teach others. It was at that table the Marist revolution. Champagnat began his ministry Brothers started. at his first parish in La Valla. Today there are more than 3,000 Champagnat was surprised when he met Marist Brothers in schools in 83 different the parishioners. They were apprehensive countries around the world continuing about their new priest because they what Marcellin Champagnat started. -

The Identity and Ethos of a Catholic Marist School 1 What Is a Catholic

The Identity and Ethos of a Catholic Marist School 1 What is a Catholic School? Jesus Christ is the centre of the Catholic School Christ is the foundation of The Catholic school finds its true the whole educational justification in the mission of the Church; it enterprise of a Catholic is based on an educational philosophy in school. which faith, culture and life are brought The Catholic School, # 34. into harmony. Through it, the local Church evangelises, educates, and contributes to the formation of a healthy and morally sound life-style among its members. The Religious Dimension of Education in a Catholic School, # 34. 1.1 Why do Catholic Schools exist? Catholic schools exist to assist parents to pass on the faith to their children. Their purpose is to provide an environment where children will see, experience, share, and come to understand a Catholic way of life and to learn what being Catholic means through the life of the school and the Religious Education curriculum. The Catholic school is a work of the Church and reflects the deepest nature of the Church. This is expressed through: • Proclaiming the word of God (kerygma-martyria) • Celebrating the sacraments (leitourgia) • Exercising charity (diakonia) 1 1.2 Defining Special Character Private Schools Conditional Integration Act (1975) is the legislation which safeguards Special Character. As a part of updating the Education Act in 2017, the PSCI Act has now been incorporated into the Education Act 1989. The Special Character of an integrated school is defined in the Integration Agreement between the Proprietor of the school and the Crown.