Historic Property Design Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OHS Site Inventories

Architectural Category – OHS Site Inventories National Register Information Historic Sites Inventories – City of Springfield Blank Site Inventory Forms “Preservation of Historic Sites in Clark County” by A. L. Slager Design Guidelines Springfield Historic Preservation Plan 1988 Demolition Correspondence – Historic Plan Erter House Miami/Little Miami Rivers & Mill Creek Surveys Springfield Gas Stations Bridges Grain Elevators NATIONAL HISTORIC REGISTER SITES Battle of Piqua – George Rodgers Clark Park Frank Bookwalter House Brewer Log House Crabill House Main St. Buildings, including Bushnell Donnel House Engine House # 5 Enon Mound First Lutheran Church John Foos Mansion Green Plain Meeting House Hertzler House High Street Historic District Hunt House/Kenton Cabin Site O. S. Kelly Cottage Lagonda Club Marketplace/Heritage Center Marquart-Mercer House & Barn P. P. Mast Historic District Myers Hall (Wittenberg) Newlove Works 3D/Or Northminster Presbyterian Church Odd Fellows Home Reeser House & Innsfallen Greenhouse South Charleston Historic District St. Joseph St. Raphael Church Warder Public Library Westcott House OHS Site Inventories, pg. 2 OHS SITE INVENTORIES Bethel Township German Township Green Township Harmony Township Madison Township Mad River Township Moorefield Township Pike Township Pleasant Township Springfield Township Springfield City 400-1520 North Belmont Street Center Street Chestnut Street Clark Street Columbia Street 2-110 West Columbia College Avenue Cypress Street Dibert Avenue Drexel Avenue 426-804 East Street 916-1024 Elder Street 473 Ellsworth 556 – 619 Elm Street Emery Street Euclid Street NW Corner of Ferncliff 26 – 840 N. Fountain Avenue 300-800 South Fountain 901-1800 South Fountain SE Corner of S. Fountain & Grand Avenue; SW Corner of Fountain & Main Street Front & Walter 354 – 629 Gallagher 211 & 623-25 Grand Avenue 425 – 613 Harrison Street 512 – 664 Homeview Jefferson Street 712 – 1501 Kenton Street 1028 Lafayette 400 – 2021 Lagonda Avenue Larch & James OHS Site Inventories, pg. -

The Stained Glass of St. Nicholas' Church, Blundellsands

The Stained Glass of St. Nicholas’ Church, Blundellsands Text: Philip Collins; Photographs: Peter Batey Of the twenty three stained glass windows in St. Nicholas’ Church, fifteen are the work of four firms and the remaining eight are by unidentified studios. Apart from the three apsidal east windows, there is no overall subject scheme, the donors, albeit in a number of cases with the input of Caröe, being apparently free to choose their own subjects. The earliest glass is a window with a commemorative date of 1875 and therefore more or less contemporary with the building of the church, and the latest, a window inserted in 1924. In the beginning, the appearance of the windows from inside would have looked quite different. For one thing, the intensity of light on a dark day would have been much stronger, but then gradually, as windows were filled over the years, the glare would have softened until the present effect we see today was reached. 1 This description of the windows follows the sequence shown on the Stained Glass Plan (see below) and it begins in the sanctuary. For studying windows 1-5 and 12-14 the use of a pair of binoculars is recommended. List of windows and page number 1. Transfiguration 4 2. Crucifixion 5 3. Ascension 7 4. St. Paul 8 5. Parable of the talents 9 6. Suffer the little children 11 7. Good works 12 8. St. Balbina and Dorcas 13 9. Martha and Mary 15 10. Good works 17 11. Christ with the doctors 19 12. War 20 13. -

Excerpt from Notre-Dame De Paris • Victor Hugo This Text Is Brought to You by The

Excerpt from Notre-Dame de Paris • Victor Hugo This text is brought to you by the Society of Amate ur Gentlemen You can visit us at http://societyofamateurgentlemen.wordpress.com/ The text of this translation is in the public domain, everyone is permitted, granted your local copyright laws allow, to distribute this however he sees fit. I ask only that you leave it intact, but that ultimately is your prerogative. Fight, draw the sword, O city of the light, Which fosters art, defends the cotter's right. Let, O proud home of man's equality, Howl round thee the foul hordes of bigotry-- Black props of throne and altar--hypocrites! Who, in all ages, have proscribed the lights; Who guard all gods against th' inquiring mind; Whose screech in every history we find-- At Thebes, Mycenae, Delphi, Memphis, Rome-- Like bark of unclean dogs from distance come. -Victor Hugo Excerpt from Paris Slandered Notre-Dame de Paris: This Will Kill That • Victor Hugo (Translated By William Neilson) This Will Kill That: Book V, Chapter II Notre-Dame de Paris By Victor Hugo OUR fair readers must forgive us if we halt a moment here and endeavor to unearth the idea hidden under the Archdeacon’s enigmatical words: This will kill That. The Book will kill the Edifice. To our mind, this thought has two aspects. In the first place it was a view pertaining to the priest—it was the terror of the ecclesiastic before a new force—printing. It was the servant of the dim sanctuary scared and dazzled by the light that streamed from Gutenberg’s press. -

Ohio Historical Site Inventories

Architectural Category Ohio Historical Sites Collection Box 1 National Register Information Historic Inventory Fact Sheets Ohio Historic Inventory Forms Ohio Historic Inventory Correspondence Clark County – Springfield General “Preservation of Historic Sites in Clark County” by A.L. Slager Design Guidelines Springfield Historic Preservation Plan 1988 Demolition Correspondence – Historic Plan Miami/Little Miami Rivers and Mill Creek Surveys CLG Grant 1986 Foreman Research Project Springfield Minority Resources Clark County Historical Society Springfield Community Development Department Springfield Historic Landmarks Commission Historical Index of Structures and Sites, Springfield, Ohio – 1977 Historical Index of Structures and Sites, Springfield, Ohio – 1977 Long Range Transportation Plan – 2012 American Tower Site Review Notification – German Township American Tower Site Review Notification – German Township Transportation – Street Projects Ace Tavern – Northeast corner Main Street and Spring Street A.F. of L. Labor Union – North side of W. High Street Alamo Club – 358 E. High Street Apartment Building – Haucke Flats – Northwest corner W. Main Street and Plum Street Arcade – East side of Fountain Avenue Arcue Building – Northwest corner High Street and Fountain Avenue Aztec Energy Systems/New York Central Railroad Office – Washington Street Barrett Publishing Company – 26 N. Fountain Avenue C.L. Bauer House – 1215 E. High Street L.F. Bauer House – 1217 E. High Street The Bayley Company – Northeast corner North Street and Wittenberg Battle of Piqua – Lower Valley Pike and Tecumseh Road Bishop’s Recreation Barn – 3330 Party Lane Frank Bookwalter House – 611 S. Fountain Avenue Clark County Bridges H.V. Bretney House – 726 E. High Street Brewer Log House – 2665 Old Springfield Road Asa Bushnell House – Richards Funeral Home – 838 E. -

Tiffany Windows in Richmond and Petersburg, Virginia Rachel M

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1997 Tiffany Windows in Richmond and Petersburg, Virginia Rachel M. Bradshaw [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons © The Author Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4389 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APPROVAL CERTIFICATE TIFFANY WINDOWS IN RICHMOND AND PETERSBURG, VIRGINIA by RACHEL M. BRADSHAW Th�sis Advisor Reader Dean, School of the Arts Dean, School of Graduate Studies 15;;c;c;i. Date TIFFANY WINDOWS IN RICHMOND AND PETERSBURG, VIRGINIA by RACHEL M. BRADSHAW B.A., Troy State University, 1991 Submitted to the Faculty of the School of the Arts of Virginia Commonwealth University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts RICHMOND, VIRGINIA April, 1997 Table of Contents Acknowledgements...... lll List of illustrations....... IV Introduction. ................................... .... Catalog ................................................. 20 Monumental Church........... 21 St. Paul's Episcopal Church.... 25 Second Presbyterian Church. ....... 62 69 Grace and Holy Trinity Church ..................... Temple Beth Ahabah ............................ 74 St. James Episcopal Church ....... 77 All Saints Episcopal Church..... 91 Ginter Park Baptist Church ...... 123 Hollywood Cemetery... 139 Old Blandford Church.. 146 Washington Street United Methodist Church........... 182 Conclusion........................................ 186 Selected Bibliography ....................................... 188 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Anne Crowe, for her patience, support, and encouragement, and my reader, Dr. -

Public Building Collection

BOX LIST Architectural Category – Public Buildings Box 1 A.B. Graham Building and Common Pleas Upgrades, 2/7/2015 Adaptive Reuse article Aleshire Parking Garage – North of National Bank Building (now razed) Arcue Building – 6 W. High Street (razed 2012) Armories in Springfield, 108 E. Mulberry Street Armory Building Improvements in Springfield - 1864 Burgess Hall – 878 E. Main Street o Reco in 2012 o Was Burgess Hall, Ann Aston Warder’s school in the 1850s o History 1835-1974 Bushnell Building – 14 E. Main Street Children’s Home – 525 E. Home Road o Specifications for Boy’s Cottage 1905 City Clock Article – 1924 City Hall Project - 1981 Clark County Jail o Schedule for building jail -1824 o 1886 article about jail in 1851 Clark County Juvenile Court and Detention Home – 30 N. Limestone St.(now razed) Clark County’s Most Impressive Buildings – 1995 o Westcott House o City Hall/MarketPlace/Heritage Center o Warder Public Library o Performing Arts Center o Springfield Museum of Art Clark County Tuberculosis Hospital – 3130 E. Main Street o Building project manual – 1925 Clark Memorial Home – 616 N. Limestone (razed) and 106 Kewbury Road Credit Life Insurance – Southwest corner Limestone and Main Core Renewal Project Courthouses of Clark County Day Nursery/Old City Jail – 350 N. Fountain Avenue Demolition permits approved - 11/13/14 o McAdams Building o Rose City Pawn o Crowell-Collier Dover Place Apartments – North Limestone Street (completed 1980) Downtown Fountain Ave Revitalization NMF 6/8/2010 MC 11/22/2013 Jackie Folck 1/7/17 Downtown Springfield – E. Main Street 1914 (Kinnane’s) and S. -

Computer-Generated Gothic Tracery with a Motif-Oriented Approach

Computer-generated Gothic Tracery with a Motif-oriented Approach Joe Takayama* *Kyushu Sangyo University, [email protected] Abstract: Drawing decorative ornaments as computer-generated imagery (CGI) is both time- and energy-intensive because it usually involves complicated motifs. Therefore, a procedural approach that is applicable to a variety of fields may be useful for drawing ornaments efficiently. Consequently, an algorithmic approach for generating complicated ornaments has been proposed in this study. This research specifically focuses on Gothic tracery, which is widely found in European architecture from the 12th to 15th centuries. Tracery constitutes stonework elements that support glass panes in windows. Although Gothic tracery comprises a wide variety of complicated patterns, it usually consists of combinations of circles with a few straight lines. These combinations and geometric operations can generate various motifs. However, it is difficult to extract the rules for obtaining desirable patterns from circle arrangements because of variations in geometric situations. Therefore, we attempted through this study to draw Gothic tracery using a motif-oriented approach whereby an algorithm automatically seeks an appropriate position in a closed 2D space for placement of the motif. Thus, the algorithm determines the arrangement of circles required to draw the motif. This algorithm can produce some principal Gothic-style motifs automatically, and recursive execution of the algorithm can generate complicated patterns. Keywords: Computer-generated imagery, Ornaments, Gothic tracery, Procedural approach 1. Introduction A procedural approach in CGI has been used mainly to represent natural objects and natural phenomena that are too complicated to be drawn or animated by artists [5]. -

Tiffany Windows in Richmond and Petersburg, Virginia

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1997 Tiffany Windows in Richmond and Petersburg, Virginia Rachel M. Bradshaw Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4389 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APPROVAL CERTIFICATE TIFFANY WINDOWS IN RICHMOND AND PETERSBURG, VIRGINIA by RACHEL M. BRADSHAW Th�sis Advisor Reader Dean, School of the Arts Dean, School of Graduate Studies 15;;c;c;i. Date TIFFANY WINDOWS IN RICHMOND AND PETERSBURG, VIRGINIA by RACHEL M. BRADSHAW B.A., Troy State University, 1991 Submitted to the Faculty of the School of the Arts of Virginia Commonwealth University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts RICHMOND, VIRGINIA April, 1997 Table of Contents Acknowledgements...... lll List of illustrations....... IV Introduction. ................................... .... Catalog ................................................. 20 Monumental Church........... 21 St. Paul's Episcopal Church.... 25 Second Presbyterian Church. ....... 62 69 Grace and Holy Trinity Church ..................... Temple Beth Ahabah ............................ 74 St. James Episcopal Church ....... 77 All Saints Episcopal Church..... 91 Ginter Park Baptist Church ...... 123 Hollywood Cemetery... 139 Old Blandford Church.. 146 Washington Street United Methodist Church........... 182 Conclusion........................................ 186 Selected Bibliography ....................................... 188 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Anne Crowe, for her patience, support, and encouragement, and my reader, Dr. -

A Study of Residential Stained Glass: the Work of Nicola D'ascenzo Studios from 1896 to 1954

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1990 A Study of Residential Stained Glass: The Work of Nicola D'Ascenzo Studios from 1896 to 1954 Lisa Weilbacker University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Weilbacker, Lisa, "A Study of Residential Stained Glass: The Work of Nicola D'Ascenzo Studios from 1896 to 1954" (1990). Theses (Historic Preservation). 252. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/252 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Weilbacker, Lisa (1990). A Study of Residential Stained Glass: The Work of Nicola D'Ascenzo Studios from 1896 to 1954. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/252 For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Study of Residential Stained Glass: The Work of Nicola D'Ascenzo Studios from 1896 to 1954 Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Weilbacker, Lisa (1990). A Study of Residential Stained Glass: The Work of Nicola D'Ascenzo Studios from 1896 to 1954. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, -

Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Immaculate Conception

Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Immaculate Conception Peoria, Illinois A Self-Guided Tour DISCOVER SAINT MARY’S Welcome to Peoria's Cathedral! In the middle ages, it was common for cathedrals to decorate their floors with elaborate labyrinths. These mazes in stone were very physical metaphors for the intentional wandering of the spiritual life. While there is no labyrinth in this cathedral, I invite you to wander nonetheless. This booklet is not designed to be an exhaustive historical guide or museum catalogue. This is not a theme park map to move you from point to point. Instead, we hope to provide a bit of history, a theological context, and an overview of this cathedral that is mother-church to Catholics across Central Illinois. I have been praying in this church both as a seminarian and a priest for over a decade. Over these past few years witnessing the grand restoration and parish life, I have especially been spending a lot of time here. I still never tire of wandering the church, talking to saints who are old friends, discovering new details in the windows, and gazing at the stars. I invite you to wander, to wonder, to pray. St. Mary of the Immaculate Conception, pray for us! Fr. Alexander Millar Rector 2 HISTORY OF SAINT MARY CATHEDRAL In 1851, Bishop James VandeVelde of Chicago asked a Vincentian missionary, Father Alphonse Montouri, CM, to build a new church in Peoria, offering him $200 to carry out the plan. In a year, St. Mary’s Church (right) was built and was said to be one of the finest churches between Chicago and St. -

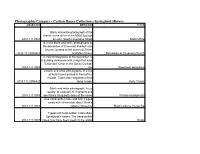

Carlton Bauer Collection - Springfield History OBJECTID DESCRIP TITLE

Photographic Category - Carlton Bauer Collection - Springfield History OBJECTID DESCRIP TITLE Black and white photograph of the interior of the office of the M&M Savings 2014.111.0001 & Loan, South Limestone Street M&M Office Set of 6 black and white photographs of the demolition of Covenant Presbyterian Church, located at the corner of Fisher 2014.111.0002A-F and Main Street. Demolition of Covenant Church 2 color photographs of the demolition of a building downtown with a sign that says "Columbia" Close to the Savoy Cocktail 2014.111.0003 Bar Downtown demolition 2 black and white photographs of a line of Kelly trucks parked in front of the Arcade. Taken from negatives of the 2014.111.0004A-D same image. Kelly Trucks Black and white photograph, fuzzy quality, of a parade of elephants and 2014.111.0005 spectators lining both sides of the street Parade of elephants One hand-written note and and 3 typed cards with information about Black's 2014.111.0006 Opera House fire Black's Opera House fire Typed and hand-written notes about Springfield's history. The hand-written 2014.111.0007 notes may have been used for the slides Notes Copies of 2 newspaper articles about the slides Carlton Bauer presented to the Springfield Photographic Society and Kiwanis. Good information about the 2014.111.0008 provenance of the slides Slide information Index cards with notes, probably on various slides. Non-sequential numbers. 2014.111.0009 Badly stained Narrative 1 large box of slides, formerly belonging to Carlton Bauer, former Springfield 2014.111.0010 realtor -

Notre Dame De Paris, by Victor Marie Hugo

Notre Dame de Paris Victor Marie Hugo The Harvard Classics Shelf of Fiction, Vol. XII. Selected by Charles William Eliot Copyright © 2001 Bartleby.com, Inc. Bibliographic Record Contents . Biographical Note Criticisms and Interpretations I. By Frank T. Marzials II. By Andrew Lang III. By G. L. Strachey List of Characters Author’s Preface to the Edition of 1831 Book I I. The Great Hall II. Pierre Gringoire III. The Cardinal IV. Master Jacques Coppenole V. Quasimodo VI. Esmeralda Book II I. From Scylla to Charybdis II. The Place de Grève III. Besos Para Golpes IV. The Mishaps Consequent on Following a Pretty Woman through the Streets at Night V. Sequel of the Mishap VI. The Broken Pitcher VII. A Wedding Night Book III I. Notre Dame II. A Bird’s-Eye View of Paris Book IV I. Charitable Souls II. Claude Frollo III. Immanis Pecoris Custos, Immanior Ipse IV. The Dog and His Master V. Further Particulars of Claude Frollo VI. Unpopularity Book V I. The Abbot of St.-Martin’s II. This Will Destroy That Book VI I. An Impartial Glance at the Ancient Magistracy II. The Rat-Hole III. The Story of a Wheaten Cake IV. A Tear for a Drop of Water V. End of the Wheaten Cake Book VII I. Showing the Danger of Confiding One’s Secret to a Goat II. Showing That a Priest and a Philosopher Are Not the Same III. The Bells IV. Fate V. The Two Men in Black VI. Of the Result of Launching a String of Seven Oaths in a Public Square VII.