Ruth Pollard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edward Irving

Edward Irving: Romantic Theology in Crisis Peter Elliott Edward Irving: Romantic theology in crisis Peter Elliott BA, BD, MTh(Hons.) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology of Murdoch University 2010 I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………… Peter Elliott Abstract In 1822 a young Church of Scotland minister named Edward Irving accepted a post in London and quickly attracted wide upper-class support. He numbered amongst his friends and admirers the political historian Thomas Carlyle and the Romantic poet-philosopher Samuel Taylor Coleridge. During the next decade, Irving developed views and practices that could be described as millenarian and proto- pentecostal; his interest in prophecy grew and his Christology became unorthodox. He was ejected from his church and hundreds followed him to begin a new group. Within a short period of time, he was relegated to a subordinate position within this group, which later became the Catholic Apostolic Church. He died in 1834 at the age of 42. This paper examines Irving’s underlying Romanticism and the influences on him, including his complex relationships with Carlyle and Coleridge, and then demonstrates how his Romanticism informed all of his key theological positions, often in tension with the more established Rationalism of the time. In ejecting Irving from his pastorate, the Church of Scotland officials were rejecting his idealistic and Romantic view of Christianity. It was this same idealism, with reference to the charismata, that alienated Irving from a senior role in the nascent Catholic Apostolic Church. -

Mr. Froude As a Biographer

JULIA WEDGWOOD 111 no less forthright and penetrating about Froude, “the trusted son who has opened the gates to the hostile crowd.” As an apt sequel to the letters of Lady Harriet Ashburton, Wedgwood’s essay on Froude’s edition of Reminiscences is published below. Together, these sources provide the impetus to establish a new critical “court of appeal,” in which the original verdicts against Carlyle can be subjected to a more scrupulous and fair-minded process of “revisal and rectification.” Mr. Froude as a Biographer. CONTEMPORARY REVIEW 39 (May, 1881): 821–42 Reminiscences. By thomas Carlyle. Edited by J. A. Froude. 2 vols. Longmans. That we should speak only good of the dead—which means, of course, of the recently dead—is a maxim founded on respect to the best part of our nature. There is always some one on whom, at such a moment, any harsh judgment on the one who is gone inflicts a peculiarly painful wound, and if by any sad chance there should be no one, then the sense of a common humanity should replace the peculiar ties which have been loosened or broken, and demand, with an even superior claim, that we should pay so forlorn a being the tribute of a respectful silence. We hurt the sense of pity, of reverence within, when we needlessly allow ourselves to put hard judgments of one recently gone from us into words, even if they are just words. And in ordinary circumstances such words are needless. That chapter is closed—with that person our relations are ended, his faults can hurt us no more. -

Edward Irving's Hybrid

chapter 11 Edward Irving’s Hybrid: Towards a Nineteenth- Century Apostolic and Presbyterian Pentecostalism Peter Elliott Introduction The London-based ministry of Edward Irving was short, stellar, and controver- sial. Born in south-west Scotland in 1792 and educated at Edinburgh University, Irving served as parish assistant to Church of Scotland minister Thomas Chalmers in Glasgow for three years from 1819 to 1822. In 1821, he received an unexpected call from the Caledonian Chapel in London to preach for them with a view to becoming their next minister, an invitation that was probably less of a compliment to Irving than a reflection of the dwindling fortunes of the congregation.1 Irving preached for them during December 1821 and took up the position as their minister in July, 1822.2 Twelve years later, in December 1834, Irving was dead at the age of 42. These twelve years from 1822 to 1834 saw a rapid rise and gradual decline in Irving’s ministerial career, if not his hopes, as during this time he became London’s most popular preacher, a published author, and a theological innovator. His theological contributions, while often focused elsewhere, had inevitable implications for the issue of leadership within the church and other religious organisations. Explosive Growth The influence of Romanticism on Irving has been frequently noted.3 Like most of his contemporaries, he was affected by the political aftermath of the 1 The congregation had dwindled to about 50 at this time, and was barely able to pay a minis- ter’s salary. Arnold Dallimore, The Life of Edward Irving: the Fore-runner of the Charismatic Movement (Edinburgh, 1983), p. -

ABSTRACT Genius, Heredity, and Family Dynamics. Samuel Taylor Coleridge and His Children: a Literary Biography Yolanda J. Gonz

ABSTRACT Genius, Heredity, and Family Dynamics. Samuel Taylor Coleridge and his Children: A Literary Biography Yolanda J. Gonzalez, Ph.D. Chairperson: Stephen Prickett, Ph.D. The children of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Hartley, Derwent, and Sara, have received limited scholarly attention, though all were important nineteenth century figures. Lack of scholarly attention on them can be blamed on their father, who has so overshadowed his children that their value has been relegated to what they can reveal about him, the literary genius. Scholars who have studied the children for these purposes all assume familial ties justify their basic premise, that Coleridge can be understood by examining the children he raised. But in this case, the assumption is false; Coleridge had little interaction with his children overall, and the task of raising them was left to their mother, Sara, her sister Edith, and Edith’s husband, Robert Southey. While studies of S. T. C.’s children that seek to provide information about him are fruitless, more productive scholarly work can be done examining the lives and contributions of Hartley, Derwent, and Sara to their age. This dissertation is a starting point for reinvestigating Coleridge’s children and analyzes their life and work. Taken out from under the shadow of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, we find that Hartley was not doomed to be a “child of romanticism” as a result of his father’s experimental approach to his education; rather, he chose this persona for himself. Conversely, Derwent is the black sheep of the family and consciously chooses not to undertake the family profession, writing poetry. -

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834)

27 OFTEN DOWN, BUT NEVER OUT SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE (1772-1834) n his quest for a livelihood, in his family life, and in his response to the Enlightenment, the Ipoet and critic Samuel Taylor Coleridge is the contrary of the lesser writer Sydney Smith. His gi- ant weeping willow overshadows Smith’s modest hawthorn, and his letters, unlike Smith’s, are the letters of an unhappy man. Coleridge’s troubles begin in childhood. In 1781, on the threshold of his ninth year, the death of his father, the Vicar of Ottery in Devon, leaves him in the charge of his brother George. After be- ing schooled at Christ’s Hospital, he goes up to Jesus College, Cambridge, where he distinguishes himself as a scholar; falls in love with Mary Evans, whose mother tends him with maternal affection when he is ill; and indulg- es in enough wayward behaviour to pile up debts he cannot pay. During a three-year period beginning when he is eighteen, he lapses from chastity in his association with loose women. In despair and shame, resisting the temptation of suicide, he enlists in the dragoons, or light cavalry, under the name Silas Tomkyn Comberbache. His friends and family succeed in trac- ing him, and after much difficulty his brothers George and James procure his discharge, ostensibly on the grounds of his insanity. Soon after returning to Cambridge, Coleridge meets Robert Southey, and the two young poets, both radicals, concoct a scheme only a little less hare-brained than the flight into the military. With other enthusiasts, they will found a Utopian colony in the United States of America to practise pantisocracy (the rule of all as equals) and aspheterism (commonality of property). -

Chapter 1 Life

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89668-9 - The Cambridge Introduction to William Wordsworth Emma Mason Excerpt More information Chapter 1 Life Education and politics 3 Coleridge 7 Home at Grasmere 9 Friendship and love 11 Tory humanist? 16 Poet Laureate 19 A longing for the company of others shaped Wordsworth’s life, one he met by forming a number of intense relationships. These relationships unfolded with friends, most notably the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge; lovers, specifi- cally Annette Vallon and Mary Hutchinson; and siblings, particularly Dorothy and John (he was not so intimate with his other two brothers, Richard and Christopher). Born in the Lake District in 1770, Wordsworth’s early life was marked by a dependency on Dorothy, to whom he was especially devoted in the absence of his father, who often worked away from home. He was also close to his mother, a figure whom he recalled as a moral and upright influence, bal- ancing his ‘moody and violent’ temperament: I remember also telling her on one week day that I had been at church, for our school stood in the churchyard, and we had frequent opportunities of seeing what was going on there. The occasion was, a woman doing penance in the church in a white sheet. My mother commended my having been present, expressing a hope that I should remember the circumstance for the rest of my life. ‘But’, said I, ‘Mama, they did not give me a penny, as I had been told they would’. ‘Oh’, said she, recanting her praises, ‘if that was your motive, you were very properly disappointed’. -

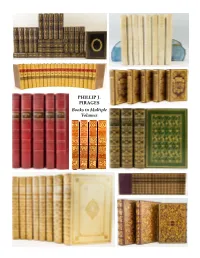

Books in Multiple Volumes PHILLIP J

PHILLIP J. PIRAGES Books in Multiple Volumes PHILLIP J. PIRAGES Fine Books and Manuscripts 1709 NE 27th Street, Suite G McMinnville, OR 97128 P: (503) 472-0476 Toll Free: (800) 962-6666 F: (503) 472-5029 [email protected] www.pirages.com Special Issue Catalogue: Sets and Books in More Than Two Volumes Please send orders and inquiries to the above physical or electronic address, and do not hesitate to telephone at any time. At this time, we are not accepting visits from new clients. Established clients may request a visit, but must contact us in advance. In addition, our website is always open. Prices are in American dollars. Shipping costs are extra. We try to build trust by offering fine quality items and by striving for precision of description because we want you to feel that you can buy from us with confidence. As part of this effort, we want you to understand that your satisfaction is unconditionally guaranteed. If you buy an item from us and are not satisfied with it, you may return it within 30 days of receipt for a refund, so long as the item has not been damaged. Most of the text of this catalogue was written by Cokie Anderson and Kaitlin Manning. Jill Mann is responsible for photography and layout. Essential administrative support has been provided by Tammy Opheim. We are pleased and grateful when you tell someone about our catalogue and when you let us know of other parties to whom we might send our publications. And we are, of course, always happy to discuss fine and interesting items that we might purchase. -

A Dialogic Study of a Poet and His Audience by Steven Mark Lane BA

How Wordsworth became Wordsworth: A Dialogic Study of a Poet and his Audience by Steven Mark Lane B.A., Simon Fraser University M.A., University of California, Santa Barbara A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Department of English Steven Mark Lane, 2007 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopying or other means, without the permission of the author. ii How Wordsworth became Wordsworth: A Dialogic Study of a Poet and his Audience By Steven Mark Lane B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1978 M.A., University of California, Santa Barbara, 1982 Supervisory Committee Supervisor: Dr. G. Kim Blank (Department of English) Departmental Member: Dr. Thomas Cleary (Department of English) Departmental Member: Dr. Eric Miller (Department of English) Outside Member: Dr. Harald Krebs (School of Music) Additional Member: Dr. Jared Curtis (Department of English, S.F.U.) iii Supervisory Committee Supervisor: Dr. G. Kim Blank Departmental Member: Dr. Thomas Cleary Departmental Member: Dr. Eric Miller Outside Member: Dr. Harald Krebs Additional Member: Dr. Jared Curtis ABSTRACT This is a study of the emergence of William Wordsworth’s literary reputation during his lifetime. It is constructed as a variety of biography, organized chronologically in order to attempt a fuller sense of the negotiation of public image and reputation that went on between Wordsworth and his audiences. Mikhail Bakhtin’s notion of dialogism structures the study as a series of “conversations,” interconnected and moving outward from self, to intimate group or coterie, to public, reviewers, and culture at large.