1 Gustav Holst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Music-Making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts

“Music-making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts Daniel Hautzinger Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Spring 2016 Hautzinger ii Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Historiography and the Origin of the Festival 9 a. Historiography 9 b. The Origin of the Festival 14 3. The Democratization of Music 19 4. Technology, Modernity, and Their Dangers 31 5. The Festival as Community 39 6. Conclusion 53 7. Bibliography 57 a. Primary Sources 57 b. Secondary Sources 58 Hautzinger iii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have come together without the help and support of several people. First, endless gratitude to Annemarie Sammartino. Her incredible intellect, voracious curiosity, outstanding ability for drawing together disparate strands, and unceasing drive to learn more and know more have been an inspiring example over the past four years. This thesis owes much of its existence to her and her comments, recommendations, edits, and support. Thank you also to Ellen Wurtzel for guiding me through my first large-scale research paper in my third year at Oberlin, and for encouraging me to pursue honors. Shelley Lee has been an invaluable resource and advisor in the daunting process of putting together a fifty-some page research paper, while my fellow History honors candidates have been supportive, helpful in their advice, and great to commiserate with. Thank you to Steven Plank and everyone else who has listened to me discuss Britten and the Aldeburgh Festival and kindly offered suggestions. -

Reading Comprehension Gustav Holst

Gustav Holst Comprehension Gustav Holst was born in Cheltenham on September 21st 1874. He came from a line of talented musicians. Holst was taught how to play the piano by his father, however a problem with his nerves ruled out a career as a pianist. He later took up the trombone instead. His first conducting job was with a local church choir which he found to be excellent experience. Holst attended the Royal College of Music where he studied composition and met fellow student, Ralph Vaughn Williams, another great composer. The two became great friends for life. Holst’s wife was a soprano. He instantly fell in love with her but she was not particularly impressed by him at first. For a while, he supported himself and his wife by playing the trombone professionally alongside composing in his spare time. Holst became a teacher and worked at St Paul’s Girls’ School, Hammersmith where they opened a new music wing in his honour in 1913. The music wing housed a sound-proof room where Holst could work without being disturbed. Holst became very interested in astrology which was the inspiration for his best known piece, ‘The Planets’. This launched him into real stardom, however he was never happy to be in the limelight as he was a shy man. The first performance of ‘The Planets’ was given in September 1918. Each movement describes the planet’s character, for example, Venus is the bringer of peace, Uranus is about a magician and Saturn is based on the bringer of old age. -

The Late Summer Newsletter

AUGUST 2020 Issue No: 17 Welcome to the late summer newsletter. AGM and the musical phrasing stand out, always with clear thought for the meaning. Furthermore, the perfect Please note that the AGM has been postponed to December velvety colouring of their basses, with no forcing of the 2020 – date/venue to follow in the next newsletter. As the Holst th lower register whatsoever, eases the tuning and Birthplace Trust annual concert scheduled for 19 September harmonic construction of the ensemble. Preece proves 2020 has been cancelled, so too must our AGM pencilled in for that Holst is more than The Planets. that afternoon. Hopefully, if concerts resume in the next three months, we could have our AGM in the afternoon of a Saturday Jerónimo Marin before Christmas with a concert in Cheltenham that evening. HOLST/ VAUGHAN WILLIAMS/ WALT WHITMAN SAVITRI Holst, Vaughan Williams and the poetry of Walt Holst’s one-act opera will be performed in the gardens of Whitman Lauderdale House, Highgate, London, with two performances each evening on August 13th, 15th, 20th and 22nd. The The poems of Walt Whitman, and in particular his production given by Hampstead Garden Opera will be staged Leaves of Grass, first published in 1855, soon inspired by Julia Mintzer and conducted by Thomas Payne (please visit new generations of English composers. These website at https://hgo.org.uk/savitri/ for further detail). included Ralph Vaughan Williams and Gustav von Holst. Vaughan Williams was introduced to Whitman’s PART SONGS BY HOLST poetry by Bertrand Russell in 1892, the year of the poet’s death. -

The Perfect Fool Free

FREE THE PERFECT FOOL PDF Stewart Lee | 288 pages | 04 Nov 2002 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9781841153667 | English | London, United Kingdom Ed Wynn: The Perfect Fool by Robin Williams | The American Vaudeville Museum Goodreads helps you The Perfect Fool track of books you want to The Perfect Fool. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh The Perfect Fool try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Stephen Lang. Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — The Perfect Fool by J. The Perfect Fool by J. Stephen Lang. Stephen J. Meet Brian Ericson, a young man whose life seems perfect in every way. He is handsome and successful, and everything is going his way with the possible exception of his relationship with Kristen, the perfect woman he just broke up with. On a Beautiful November day, Brian sets out for a three-day weekend in the mountains. Taking what he believes will be a shortcut, things su Meet Brian Ericson, a young man whose life seems perfect in every way. Taking what he believes will be a shortcut, things suddenly take a turn for the worse. Lost and disoriented, Brian gets some help from a host of surprising characters, and must grapple with the foolish choices of his life. Download the Readers' Guide. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published January 28th The Perfect Fool David C. Cook first published January More Details Original Title. Friend Reviews. To see The Perfect Fool your friends thought of this book, please sign up. -

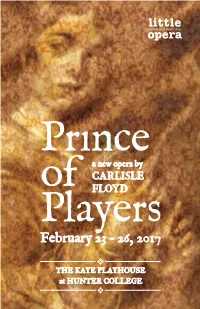

View the Program!

cast EDWARD KYNASTON Michael Kelly v Shea Owens 1 THOMAS BETTERTON Ron Loyd v Matthew Curran 1 VILLIERS, DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM Bray Wilkins v John Kaneklides 1 MARGARET HUGHES Maeve Höglund v Jessica Sandidge 1 LADY MERESVALE Elizabeth Pojanowski v Hilary Ginther 1 about the opera MISS FRAYNE Heather Hill v Michelle Trovato 1 SIR CHARLES SEDLEY Raùl Melo v Set in Restoration England during the time of King Charles II, Prince of Neal Harrelson 1 Players follows the story of Edward Kynaston, a Shakespearean actor famous v for his performances of the female roles in the Bard’s plays. Kynaston is a CHARLES II Marc Schreiner 1 member of the Duke’s theater, which is run by the actor-manager Thomas Nicholas Simpson Betterton. The opera begins with a performance of the play Othello. All of NELL GWYNN Sharin Apostolou v London society is in attendance, including the King and his mistress, Nell Angela Mannino 1 Gwynn. After the performance, the players receive important guests in their HYDE Daniel Klein dressing room, some bearing private invitations. Margaret Hughes, Kynaston’s MALE EMILIA Oswaldo Iraheta dresser, observes the comings and goings of the others, silently yearning for her FEMALE EMILIA Sahoko Sato Timpone own chance to appear on the stage. Following another performance at the theater, it is revealed that Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, has long been one STAGE HAND Kyle Guglielmo of Kynaston’s most ardent fans and admirers. SAMUEL PEPYS Hunter Hoffman In a gathering in Whitehall Palace, Margaret is presented at court by her with Robert Balonek & Elizabeth Novella relation Sir Charles Sedley. -

The Perfect Fool (1923)

The Perfect Fool (1923) Opera and Dramatic Oratorio on Lyrita An OPERA in ONE ACT For details visit https://www.wyastone.co.uk/all-labels/lyrita.html Libretto by the composer William Alwyn. Miss Julie SRCD 2218 Cast in order of appearance Granville Bantock. Omar Khayyám REAM 2128 The Wizard Richard Golding (bass) Lennox Berkeley. Nelson The Mother Pamela Bowden (contralto) SRCD 2392 Her son, The Fool speaking part Walter Plinge Geoffrey Bush. Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime REAM 1131 Three girls: Alison Hargan (soprano) Gordon Crosse. Purgatory SRCD 313 Barbara Platt (soprano) Lesley Rooke (soprano) Eugene Goossens. The Apocalypse SRCD 371 The Princess Margaret Neville (soprano) Michael Hurd. The Aspern Papers & The Night of the Wedding The Troubadour John Mitchinson (tenor) The Traveller David Read (bass) SRCD 2350 A Peasant speaking part Ronald Harvi Walter Leigh. Jolly Roger or The Admiral’s Daughter REAM 2116 Narrator George Hagan Elizabeth Maconchy. Héloïse and Abelard REAM 1138 BBC Northern Singers (chorus-master, Stephen Wilkinson) Thea Musgrave. Mary, Queen of Scots SRCD 2369 BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra (Leader, Reginald Stead) Conducted by Charles Groves Phyllis Tate. The Lodger REAM 2119 Produced by Lionel Salter Michael Tippett. The Midsummer Marriage SRCD 2217 A BBC studio recording, broadcast on 7 May 1967 Ralph Vaughan Williams. Sir John in Love REAM 2122 Cover image : English: Salamander- Bestiary, Royal MS 1200-1210 REAM 1143 2 REAM 1143 11 drowned in a surge of trombones. (Only an ex-addict of Wagner's operas could have 1 The WIZARD is performing a magic rite 0.21 written quite such a devastating parody as this.) The orchestration is brilliant throughout, 2 WIZARD ‘Spirit of the Earth’ 4.08 and in this performance Charles Groves manages to convey my father's sense of humour Dance of the Spirits of the Earth with complete understanding and infectious enjoyment.” 3 WIZARD. -

EMR 11818 Holst the Perfect Fool

The Perfect Fool (The ballet from the opera) Wind Band / Concert Band / Harmonie / Blasorchester Arr.: Jan Valta Gustav Holst EMR 11818 st 1 Score 2 1 Trombone + st nd 4 1 Flute 2 2 Trombone + nd 4 2 Flute / Piccolo 2 Bass Trombone + 1 Oboe (optional) 2 Baritone + 1 Bassoon (optional) 2 E Bass 1 E Clarinet (optional) 2 B Bass st 5 1 B Clarinet 2 Tuba 4 2nd B Clarinet 1 String Bass (optional) 4 3rd B Clarinet 1 Timpani 1 B Bass Clarinet (optional) 1 1st Percussion (Glockenspiel / Xylophone / B.D.) 1 B Soprano Saxophone (optional) 1 2nd Percussion (B.D. / Suspended Cymbal / Tam-Tam) 2 1st E Alto Saxophone 1 3rd Percussion (Tambourine / Jingles (Sleigh Bells) / 2 2nd E Alto Saxophone Vibraphone) 2 B Tenor Saxophone 1 E Baritone Saxophone (optional) Special Parts 1 E Trumpet / Cornet (optional) 1 1st B Trombone 2 1st B Trumpet / Cornet 1 2nd B Trombone 2 2nd B Trumpet / Cornet 1 B Bass Trombone 2 3rd B Trumpet / Cornet 1 B Baritone 2 1st F & E Horn 1 E Tuba 2 2nd F & E Horn 1 B Tuba 2 3rd F & E Horn Print & Listen Recorded on CD - Auf CD aufgenommen - Enregistré sur CD | Photocopying The Perfect Fool is illegal! (The ballet from the opera) Gustav Holst Arr.: Jan Valta 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Andante ( = 76) q L'istesso tempo ( q. = 76) 1st Flute p Fl. 2nd Flute / Piccolo p Oboe p Bassoon 3 ff p cresc. f (play if no Oboe) p 1st B b Clarinet p 2nd B Clarinet b p 3rd B Clarinet b 3 p Bb Bass Clarinet p cresc. -

Download the Concert Programme (PDF)

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Thursday 18 May 2017 7.30pm Barbican Hall Vaughan Williams Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus Brahms Double Concerto INTERVAL Holst The Planets – Suite Sir Mark Elder conductor Roman Simovic violin Tim Hugh cello Ladies of the London Symphony Chorus London’s Symphony Orchestra Simon Halsey chorus director Concert finishes approx 9.45pm Supported by Baker McKenzie 2 Welcome 18 May 2017 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief Welcome to tonight’s LSO concert at the Barbican. BMW LSO OPEN AIR CLASSICS 2017 This evening we are joined by Sir Mark Elder for the second of two concerts this season, as he conducts The London Symphony Orchestra, in partnership with a programme of Vaughan Williams, Brahms and Holst. BMW and conducted by Valery Gergiev, performs an all-Rachmaninov programme in London’s Trafalgar It is always a great pleasure to see the musicians Square this Sunday 21 May, the sixth concert in of the LSO appear as soloists with the Orchestra. the Orchestra’s annual BMW LSO Open Air Classics Tonight, after Vaughan Williams’ Five Variants of series, free and open to all. Dives and Lazarus, the LSO’s Leader Roman Simovic and Principal Cello Tim Hugh take centre stage for lso.co.uk/openair Brahms’ Double Concerto. We conclude the concert with Holst’s much-loved LSO WIND ENSEMBLE ON LSO LIVE The Planets, for which we welcome the London Symphony Chorus and Choral Director Simon Halsey. The new recording of Mozart’s Serenade No 10 The LSO premiered the complete suite of The Planets for Wind Instruments (‘Gran Partita’) by the LSO Wind in 1920, and we are thrilled that the 2002 recording Ensemble is now available on LSO Live. -

GUSTAV HOLST (1874 - 1934) 1 a Fugal Overture Op

SRCD.222 STEREO ADD GUSTAV HOLST (1874 - 1934) 1 A Fugal Overture Op. 40 No. 1 (1922)* * (5'12") 2 A Somerset Rhapsody Op. 21 No. 2 (1906 - 7) (9'01") Beni Mora - Oriental Suite Op. 29 No. 1 (1909 - 10) (17'13") 3 First Dance 4 Second Dance Fugal Overture 5 In the Street of the Ouled Näils Somerset Rhapsody 6 Hammersmith - A Prelude & Scherzo Beni Mora for Orchestra Op. 52 (1930 - 1931) (13'40") Hammersmith 7 Scherzo (1933 - 4) (5'29") Scherzo Japanese Suite Op. 33 (1915)* (11'04") Japanese Suite 8 Prelude - Song of the Fisherman 9 Ceremonial Dance 10 Dance of the Marionette 11 Interlude - Song of the Fisherman 12 Dance under the Cherry Tree 13 Finale - Dance of the Wolves London Philharmonic Orchestra *London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Sir Adrian Boult The above individual timings will normally include two pauses, one before the beginning and one after the end of each work or movement. P 1972 * P 1971 ** P 1968 The copyright in these sound recordings is owned by Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. This compilation and the digital remastering P 1992 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. C 1992 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Lyrita is a registered trade mark. Made in the U.K. London Philharmonic Orchestra London Symphony Orchestra LYRITA RECORDED EDITION. Produced under an exclusive license from Lyrita • by Wyastone Estate Ltd, PO Box 87, Monmouth, NP25 3WX, UK 8 1 the very end, when it was too late, he found it. Holst composed between 1914 and 1916. He had completed six of the movements, leaving only to be written, when he broke off in 1915 to compose the This was written at the request of a Japanese dancer, Michio Ito, who was appearing at the London Coliseum and wanted a work based on ancient Japanese melodies. -

RVW Final Feb 06 21/2/06 12:44 PM Page 1

RVW Final Feb 06 21/2/06 12:44 PM Page 1 Journal of the No.35 February 2006 In this issue... James Day on Englishness page 3 RVWSociety Tony Williams on Whitman page 7 Simona Pakenham writes for the Journal To all Members: page 11 Em Marshall on Holst Can you help? page 14 Six pages of CD and DVD reviews Our f irst r ecording v enture – the rar e songs of Vaughan Williams – has r eached a Page 22 critical point such that we no w need at least 100 members to each support us with a £100 subscription. Could you help us? and more . The project The rare songs will fill two CDs. We begin with Songs from the Operas and this includes ten songs from Hugh the Drover, arranged by the composer for voice and piano. These are world premiere recordings in this arrangement and are all quite lo vely. Our second CD covers the CHAIRMAN Early Years and includes man y songs ne ver previously recorded. These two CDs will be Stephen Connock MBE recorded in 2006-07 and issued separately thereafter. 65 Marathon House 200 Marylebone Road There is much wonderful music here, so rare and yet of such quality!The overall project will London NW1 5PL cost around £25,000 using the f inest singers and state of the art recording. We do not want Tel: 01728 454820 to compromise on quality – thus our need for members’support to drive the project forward. Fax: 01728 454873 [email protected] The Subscriptions’ benefits Both CDs will cost over £25,000. -

Guild Gmbh Guild -Historical Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen/TG, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - E-Mail: [email protected] CD-No

Guild GmbH Guild -Historical Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen/TG, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Composer/Track Artists GHCD 2201 Parsifal Act 2 Richard Wagner The Metropolitan Opera 1938 - Flagstad, Melchior, Gabor, Leinsdorf GHCD 2202 Toscanini - Concert 14.10.1939 FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) Symphony No.8 in B minor, "Unfinished", D.759 NBC Symphony, Arturo Toscanini RICHARD STRAUSS (1864-1949) Don Juan - Tone Poem after Lenau, op. 20 FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN (1732-1809) Symphony Concertante in B flat Major, op. 84 JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750) Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor (Orchestrated by O. Respighi) GHCD Le Nozze di Figaro Mozart The Metropolitan Opera - Breisach with Pinza, Sayão, Baccaloni, Steber, Novotna 2203/4/5 GHCD 2206 Boris Godounov, Selections Moussorgsky Royal Opera, Covent Garden 1928 - Chaliapin, Bada, Borgioli GHCD Siegfried Richard Wagner The Metropolitan Opera 1937 - Melchior, Schorr, Thorborg, Flagstad, Habich, 2207/8/9 Laufkoetter, Bodanzky GHCD 2210 Mahler: Symphony No.2 Gustav Mahler - Symphony No.2 in C Minor „The Resurrection“ Concertgebouw Orchestra, Otto Klemperer - Conductor, Kathleen Ferrier, Jo Vincent, Amsterdam Toonkunstchoir - 1951 GHCD Toscanini - Concert 1938 & RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872-1958) Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis NBC Symphony, Arturo Toscanini 2211/12 1942 JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) Symphony No. 3 in F Major, op. 90 GUISEPPE MARTUCCI (1856-1909) Notturno, Novelletta; PETER IILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840- 1893) Romeo and Juliet -

Concerts with the London Philharmonic Orchestra for Seasons 1946-47 to 2006-07 Last Updated April 2007

Artistic Director NEVILLE CREED President SIR ROGER NORRINGTON Patron HRH PRINCESS ALEXANDRA Concerts with the London Philharmonic Orchestra For Seasons 1946-47 To 2006-07 Last updated April 2007 From 1946-47 until April 1951, unless stated otherwise, all concerts were given in the Royal Albert Hall. From May 1951 onwards, unless stated otherwise, all concerts were given in The Royal Festival Hall. 1946-47 May 15 Victor De Sabata, The London Philharmonic Orchestra (First Appearance), Isobel Baillie, Eugenia Zareska, Parry Jones, Harold Williams, Beethoven: Symphony 8 ; Symphony 9 (Choral) May 29 Karl Rankl, Members Of The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Kirsten Flagstad, Joan Cross, Norman Walker Wagner: The Valkyrie Act 3 - Complete; Funeral March And Closing Scene - Gotterdammerung 1947-48 October 12 (Royal Opera House) Ernest Ansermet, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Clara Haskil Haydn: Symphony 92 (Oxford); Mozart: Piano Concerto 9; Vaughan Williams: Fantasia On A Theme Of Thomas Tallis; Stravinsky: Symphony Of Psalms November 13 Bruno Walter, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Isobel Baillie, Kathleen Ferrier, Heddle Nash, William Parsons Bruckner: Te Deum; Beethoven: Symphony 9 (Choral) December 11 Frederic Jackson, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Ceinwen Rowlands, Mary Jarred, Henry Wendon, William Parsons, Handel: Messiah Jackson Conducted Messiah Annually From 1947 To 1964. His Other Performances Have Been Omitted. February 5 Sir Adrian Boult, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Joan Hammond, Mary Chafer, Eugenia Zareska,