House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fighting Economic Crime - a Shared Responsibility!

THIRTY-SEVENTH INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON ECONOMIC CRIME SUNDAY 1st SEPTEMBER - SUNDAY 8th SEPTEMBER 2019 JESUS COLLEGE, UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE Fighting economic crime - a shared responsibility! Centre of Development Studies The 37th Cambridge International Symposium on Economic Crime Fighting economic crime- a shared responsibility! The thirty-seventh international symposium on economic crime brings together, from across the globe, a unique level and depth of expertise to address one of the biggest threats facing the stability and development of all our economies. The overarching theme for the symposium is how we can better and more effectively work together in preventing, managing and combating the threat posed by economically motivated crime and abuse. The programme underlines that this is not just the responsibility of the authorities, but us all. These important and timely issues are considered in a practical, applied and relevant manner, by those who have real experience whether in law enforcement, regulation, compliance or simply protecting their own or another’s business. The symposium, albeit held in one of the world’s leading universities, is not a talking shop for those with vested interests or for that matter an academic gathering. We strive to offer a rich and deep analysis of the real issues and in particular threats to our institutions and economies presented by economic crime and abuse. Well over 700 experts from around the world will share their experience and knowledge with other participants drawn from policy makers, law enforcement, compliance, regulation, business and the professions. The programme is drawn up with the support of a number of agencies and organisations across the globe and the Organising Institutions and principal sponsors greatly value this international commitment. -

Foresight Hindsight

Hindsight, Foresight ThinkingI Aboutnsight, Security in the Indo-Pacific EDITED BY ALEXANDER L. VUVING DANIEL K. INOUYE ASIA-PACIFIC CENTER FOR SECURITY STUDIES HINDSIGHT, INSIGHT, FORESIGHT HINDSIGHT, INSIGHT, FORESIGHT Thinking About Security in the Indo-Pacific Edited by Alexander L. Vuving Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies Hindsight, Insight, Foresight: Thinking About Security in the Indo-Pacific Published in September 2020 by the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, 2058 Maluhia Rd, Honolulu, HI 96815 (www.apcss.org) For reprint permissions, contact the editors via [email protected] Printed in the United States of America Cover Design by Nelson Gaspar and Debra Castro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Name: Alexander L. Vuving, editor Title: Hindsight, Insight, Foresight: Thinking About Security in the Indo-Pacific / Vuving, Alexander L., editor Subjects: International Relations; Security, International---Indo-Pacific Region; Geopolitics---Indo-Pacific Region; Indo-Pacific Region JZ1242 .H563 2020 ISBN: 978-0-9773246-6-8 The Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies is a U.S. Depart- ment of Defense executive education institution that addresses regional and global security issues, inviting military and civilian representatives of the United States and Indo-Pacific nations to its comprehensive program of resident courses and workshops, both in Hawaii and throughout the Indo-Pacific region. Through these events the Center provides a focal point where military, policy-makers, and civil society can gather to educate each other on regional issues, connect with a network of committed individuals, and empower themselves to enact cooperative solutions to the region’s security challenges. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Hybrid Warfare and the Protection of Civilians in Ukraine

ENTERING THE GREY-ZONE: Hybrid Warfare and the Protection of Civilians in Ukraine civiliansinconflict.org i RECOGNIZE. PREVENT. PROTECT. AMEND. PROTECT. PREVENT. RECOGNIZE. Cover: June 4, 2013, Spartak, Ukraine: June 2021 Unexploded ordnances in Eastern Ukraine continue to cause harm to civilians. T +1 202 558 6958 E [email protected] civiliansinconflict.org ORGANIZATIONAL MISSION AND VISION Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) is an international organization dedicated to promoting the protection of civilians in conflict. CIVIC envisions a world in which no civilian is harmed in conflict. Our mission is to support communities affected by conflict in their quest for protection and strengthen the resolve and capacity of armed actors to prevent and respond to civilian harm. CIVIC was established in 2003 by Marla Ruzicka, a young humanitarian who advocated on behalf of civilians affected by the war in Iraq and Afghanistan. Honoring Marla’s legacy, CIVIC has kept an unflinching focus on the protection of civilians in conflict. Today, CIVIC has a presence in conflict zones and key capitals throughout the world where it collaborates with civilians to bring their protection concerns directly to those in power, engages with armed actors to reduce the harm they cause to civilian populations, and advises governments and multinational bodies on how to make life-saving and lasting policy changes. CIVIC’s strength is its proven approach and record of improving protection outcomes for civilians by working directly with conflict-affected communities and armed actors. At CIVIC, we believe civilians are not “collateral damage” and civilian harm is not an unavoidable consequence of conflict—civilian harm can and must be prevented. -

Open PDF 203KB

Foreign Affairs Committee Oral evidence: FCO-DFID merger, HC 525 Tuesday 7 July 2020 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 7 July 2020. Watch the meeting Members present: Tom Tugendhat (Chair); Alicia Kearns; Stewart Malcolm McDonald; Bob Seely; Henry Smith; Royston Smith. Questions 1 - 41 Witnesses I: Tim Durrant, Associate Director, Institute for Government; and Lord Macpherson of Earl’s Court CBE, former Permanent Secretary, HM Treasury. Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Tim Durrant and Lord Macpherson. Q1 Chair: Welcome to this afternoon’s session of the Foreign Affairs Committee. Lord Macpherson and Tim Durrant, I apologise to both of you for keeping you waiting. May I ask if you would very briefly say one line about yourselves? Lord Macpherson: I was permanent secretary of the Treasury from 2005 to 2016. Tim Durrant: I am an associate director at the Institute for Government, and I have looked at machinery of government changes in the past. Q2 Chair: We are going to go through a series of questions. May I ask you to keep your answers as brief as is reasonable? If you agree with your fellow speaker, do not feel the need to repeat. If you disagree, of course feel the need to challenge. That is very welcome. We are looking at the merger of the Foreign Office and the Department for International Development. Lord Macpherson, do you agree with the rationale that the Government have set out, and the timing? Lord Macpherson: In broad terms, I can see a case for bringing the Foreign Office and Development together. -

Environment Bill (Report Stage Decisions)

Report Stage: Wednesday 26 May 2021 Environment Bill (Report Stage Decisions) This document sets out the fate of each clause, schedule, amendment and new clause considered at report stage. A glossary with key terms can be found at the end of this document. NEW CLAUSES AND NEW SCHEDULES RELATING TO PART 6; AMENDMENTS TO PART 6; NEW CLAUSES AND NEW SCHEDULES RELATING TO PART 7; AMENDMENTS TO PART 7; NEW CLAUSES AND NEW SCHEDULES RELATING TO CLAUSES 132 TO 139; AMENDMENTS TO CLAUSES 132 TO 139 NEW CLAUSES AND NEW SCHEDULES RELATING TO PART 6 Secretary George Eustice Agreed to NC21 To move the following Clause— “Habitats Regulations: power to amend general duties (1) The Secretary of State may by regulations amend the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017 (S.I. 2017/1012) (the “Habitats Regulations”), as they apply in relation to England, for the purposes in subsection (2). 5 (2) The purposes are—— (a) to require persons within regulation 9(1) of the Habitats Regulations to exercise functions to which that regulation applies— (i) to comply with requirements imposed by regulations 10 under this section, or (ii) to further objectives specified in regulations under this section, instead of exercising them to secure compliance with the requirements of the Directives; 15 (b) to require persons within regulation 9(3) of the Habitats Regulations, when exercising functions to which that regulation applies, to have regard to matters specified by regulations under this section instead of the requirements of the Directives. (3) The regulations may impose requirements, or specify objectives or 20 matters, relating to— (a) targets in respect of biodiversity set by regulations under section 1; 2 Wednesday 26 May 2021 REPORT STAGE (b) improvements to the natural environment which relate to biodiversity and are set out in an environmental improvement 25 plan. -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

Arts & Culture Environment Communities Society Health

POLITICS ECONOMY SOCIETY GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT HEALTH ARTS & CULTURE COMMUNITIES INNOVATION 10:30 - 11:20 The Rt. Hon. Rory Stew- Capitalism: Success or Overlooked Communties Britain’s Place in the From Zero to Hero: Tech for Good: How Conservative Islam in Is There Such Thing as Competition in Digital art MP in Conversation Failure? and Undervalued World: Have Your Say! Attainable Target or can New Technology Liberal Britain Community in the UK? Markets with Ayesha Hazarika Led by the IEA Individuals: Making the Led by the British Foreign Policy Headed for Failure? Transform Public Health Led by the Unfinished Revolution Led by the Local Trust Led by Coadec Group Led by Radix Anna Isaac | Lee Rowley MP | Most of all of Modern Led by Bright Blue Led by JUUL Labs Nora Mulready | Andrew Cop- David Goodhart | Jo Phillips Jeff Lynn | Professor Phillip Asa Bennett | Rt. Hon Tobias Rt Hon. Rory Stewart MP | Christopher Snowdon | Miatta Ryan Shorthouse | Kiri Hanks | David Savage | Sarah Hesz son | Shabnam Nasimi | Resham | Professor Jon Lawrence | Jo Marsden | Michael Quigley | Britain Ellwood MP | Sophia Gaston | Ayesha Hazarika Fahnbulleh Barny Evans | Peter Kyle MP | Kotecha Bambrough | Cash Carraway Vinous Ali Mark Essex | Emma Revie | Guy Adrian Wooldridge | Sofia Carl Bayliss Opperman MP | Fancy Sinantha Ignatidou 11:40 - 12:30 Defending Democracy: How do we Repurpose How do we End Home- Pathways to a No More Hot Air: From In Conversation with Capitalism: What Should How do we Bring Britain Online Harms: How do Tackling Intimidation Capitalism for the lessness in Great Britain Prosperous Planet Pollution to Solution the Rt. -

Oral Evidence: the Work of the Cabinet Office, HC 118

Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee Oral evidence: The work of the Cabinet Office, HC 118 Wednesday 29 April 2020 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 29 April 2020. Watch the meeting Members present: Mr William Wragg (Chair); Ronnie Cowan; Jackie Doyle-Price; Chris Evans; Rachel Hopkins; Mr David Jones; David Mundell; Tom Randall; Lloyd Russell-Moyle; Karin Smyth; John Stevenson. Questions 172 - 286 Witness I: Rt Hon Michael Gove MP, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office. Examination of witness Witness: Rt Hon Michael Gove MP. [This evidence was taken by video conference] Q172 Chair: Good afternoon and welcome to another virtual public meeting of the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee. I am in a Committee Room at Portcullis House with a small number of staff required to facilitate the meeting, suitably socially distanced from one another, and my other colleagues and the witness are at their homes and offices across the country. The Committee is grateful to the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster for making time to appear before us today. At the beginning of the Parliament it is usual for Committees to see their departmental Secretary of State to consider the work programme and priorities for the year ahead. However, we find ourselves in exceptional times and therefore today we will concentrate our questions on the ongoing coronavirus pandemic and the Cabinet Office’s response to it. We will postpone other questions on areas of responsibility for other weeks in the future. Members have agreed their questions. -

Liaison Committee Oral Evidence from the Prime Minister, HC 1144

Liaison Committee Oral evidence from the Prime Minister, HC 1144 Wednesday 13 January 2021 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 13 January 2021. Watch the meeting Members present: Sir Bernard Jenkin (Chair); Hilary Benn; Mr Clive Betts; Sir William Cash; Yvette Cooper; Philip Dunne; Robert Halfon; Meg Hillier; Simon Hoare; Jeremy Hunt; Darren Jones; Catherine McKinnell; Caroline Nokes; Stephen Timms; Tom Tugendhat; Pete Wishart. Questions 1-103 Witness I: Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP, Prime Minister. Examination of witness Witness: Boris Johnson MP. Q1 Chair: I welcome everyone to this session of the Liaison Committee and thank the Prime Minister for joining us today. Prime Minister, we are doing our best to set a good example of compliance with the covid rules. Apart from you and me, everyone else is working from their own premises. This session is the December session that was held over until now, for your convenience, Prime Minister. I hope you can confirm that there will still be three 2021 sessions? The Prime Minister: I can indeed confirm that, Sir Bernard, and I look forward very much to further such sessions this year. Chair: The second part of today’s session will concentrate on the UK post Brexit, but we start with the Government’s response to covid. Jeremy Hunt. Q2 Jeremy Hunt: Prime Minister, thank you for joining us at such a very busy time. It is obviously horrific right now on the NHS frontline. I wondered if we could just start by you updating us on what the situation is now in our hospitals. -

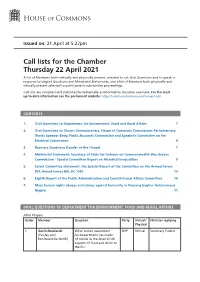

View Call List: Chamber PDF File 0.08 MB

Issued on: 21 April at 5.27pm Call lists for the Chamber Thursday 22 April 2021 A list of Members, both virtually and physically present, selected to ask Oral Questions and to speak in response to Urgent Questions and Ministerial Statements; and a list of Members both physically and virtually present selected to participate in substantive proceedings. Call lists are compiled and published incrementally as information becomes available. For the most up-to-date information see the parliament website: https://commonsbusiness.parliament.uk/ CONTENTS 1. Oral Questions to Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs 1 2. Oral Questions to Church Commissioners, House of Commons Commission, Parliamentary Works Sponsor Body, Public Accounts Commission and Speaker’s Committee on the Electoral Commission 4 3. Business Questions (Leader of the House) 7 4. Ministerial Statement: Secretary of State for Defence on Commonwealth War Graves Commission - Special Committee Report on Historical Inequalities 9 5. Select Committee statement: the Special Report of the Committee on the Armed Forces Bill, Armed Forces Bill, HC 1281 10 6. Eighth Report of the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee 10 7. Mass human rights abuses and crimes against humanity in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region 11 ORAL QUESTIONS TO DEPARTMENT FOR ENVIRONMENT, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS After Prayers Order Member Question Party Virtual/ Minister replying Physical 1 Gavin Newlands What recent assessment SNP Virtual Secretary Eustice (Paisley and his Department has made Renfrewshire North) of trends in the level of UK exports of food and drink to the EU. 2 Thursday 22 April 2021 Order Member Question Party Virtual/ Minister replying Physical 2 Deidre Brock Supplementary SNP Virtual Secretary Eustice (Edinburgh North and Leith) 3 + 4 Alex Cunningham What discussions he has had Lab Virtual Secretary Eustice (Stockton North) with the Home Secretary on reducing dog thefts. -

Centre Write Spring 2018

Centre Write Spring 2018 GlobalGlobal giant? giant Tom Tugendhat MP | Baroness Helic | Lord Heseltine | Shanker Singham 2 Contents EDITORIAL A FORCE FOR GOOD? Editor’s note Was and is the UK a force for good Laura Round 4 in the world? Director’s note Kwasi Kwarteng MP and Joseph Harker 11 Ryan Shorthouse 5 The home of human rights Letters to the editor 6 Sir Michael Tugendhat 13 The end of human rights in Hong Kong? FREE TRADING NATION Benedict Rogers 14 A global leader in free trade? Aid to our advantage Shanker Singham 7 The Rt Hon Andrew Mitchell MP 16 Compass towards the Commonwealth #MeToo on the front line Sir Lockwood Smith 8 Chloe Dalton and Baroness Helic 17 Theresa’s Irish trilemma Constitutional crisis? John Springford 10 Professor Vernon Bogdanor 18 Page 7 Shanker Singham examines the future of UK trade after Brexit Clem Onojeghuo Bright Blue is an independent think tank and pressure group Page 21 The Centre Write for liberal conservatism. interview: Tom Tugendhat MP Director: Ryan Shorthouse Chair: Matthew d’Ancona Board of Directors: Rachel Johnson, Alexandra Jezeph, Diane Banks, Phil Clarke & Richard Mabey Editor: Laura Round brightblue.org.uk Print: Aquatint | aquatint.co.uk Matthew Plummer Design: Chris Solomons CONTENTS 3 Emergency first responder A record to be proud of Strongly soft Theo Clarke 20 Eamonn Ives 30 Damian Collins MP 38 THE CENTRE WRITE INTERVIEW: DEFENCE OF THE REALM TEA FOR TWO Tom Tugendhat MP 21 Acting in Alliance with Lord Heseltine Peter Quentin 31 Laura Round 39 BRIGHT BLUE POLITICS The relevance of our Why I’m a Bright Blue MP deterrence CULTURE The Rt Hon Anna Soubry MP 24 The Rt Hon Julian Lewis MP 32 Film: Darkest Hour Research overview Fighting fit Phillip Box 41 Sam Hall 24 James Wharton 33 The future of war: A history Tamworth Prize winner 2017 Jihadis and justice (Sir Lawrence Freedman) David Verghese 26 Dr Julia Rushchenko 34 Ryan Shorthouse 42 Transparent diplomacy Sticking with the deal Exhibition: Impressionists in London James Dobson 28 Nick King 36 Eamonn Ives 43 Page 17 #MeToo on the front line.