Vice Presidential Secrecy: a Study in Comparative Constitutional Privilege and Historical Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Files on the Famous–And Infamous

Federal Files on the Famous–and Infamous The collections of personnel records at the National Archives available. Digital copies of PEPs can be purchased on CD/DVDs. include files that document military and civilian service for The price of the disc depends on the number of pages contained persons who are well known to the public for many reasons. in the original paper record and range from $20 (100 pages or These individuals include celebrated military leaders, less) to $250 (more than 1,800 pages). For more information or Medal of Honor recipients, U.S. Presidents, members of to order copies of digitized PEP records only, please write to pep. Congress, other government officials, scientists, artists, [email protected]. Archival staff are in the process of identifying entertainers, and sports figures—individuals noted for the records of prominent civilian employees whose names will personal accomplishments as well as persons known for their be added to the list. Other individuals whose records are now infamous activities. available for purchase on CD are: The military service departments and NARA have Creighton W. Abrams, Grover Cleveland Alexander, identified over 500 such military records for individuals Desi Arnaz, Joe L. Barrow, John M. Birch, Hugo L. Black, referred to as “Persons of Exceptional Prominence” (PEP). Gregory Boyington, Prescott S. Bush, Smedley Butler, Evans Many of these records are now open to the public earlier F. Carlson, William A. Carter, Adna R. Chaffee, Claire than they otherwise would have been (62 years after the Chennault, Mark W. Clark, Benjamin O. Davis. separation dates) as the result of a special agreement that Also, George Dewey, William Donovan, James H. -

June 11, 2021 the Honorable Xavier Becerra Secretary Department of Health and Human Services 200 Independence Ave S.W. Washingto

June 11, 2021 The Honorable Xavier Becerra Secretary Department of Health and Human Services 200 Independence Ave S.W. Washington, D.C. 20201 The Honorable Francis Collins, M.D., Ph.D. Director National Institutes of Health 9000 Rockville Pike Rockville, MD 20892 Dear Secretary Becerra and Director Collins, Pursuant to 5 U.S.C. § 2954 we, as members of the United States Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, write to request documents regarding the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. The recent release of approximately 4,000 pages of NIH email communications and other documents from early 2020 has raised serious questions about NIH’s handling of COVID-19. Between June 1and June 4, 2021, the news media and public interest groups released approximately 4,000 pages of NIH emails and other documents these organizations received pursuant to Freedom of Information Act requests.1 These documents, though heavily redacted, have shed new light on NIH’s awareness of the virus’ origins in the early stages of the COVID- 19 pandemic. In a January 9, 2020 email, Dr. David Morens, Senior Scientific Advisor to Dr. Fauci, emailed Dr. Peter Daszak, President of EcoHealth Alliance, asking for “any inside info on this new coronavirus that isn’t yet in the public domain[.]”2 In a January 27, 2020 reply, Dr. Daszak emailed Dr. Morens, with the subject line: “Wuhan novel coronavirus – NIAID’s role in bat-origin Covs” and stated: 1 See Damian Paletta and Yasmeen Abutaleb, Anthony Fauci’s pandemic emails: -

Public Opinion As a Meager Influence in Shaping Contemporary Supreme Court Decision Making

Michigan Law Review Volume 109 Issue 6 2011 But How Will the People Know? Public Opinion as a Meager Influence in Shaping Contemporary Supreme Court Decision Making Tom Goldstein SCOTUSblog Amy Howe SCOTUSblog Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Judges Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Tom Goldstein & Amy Howe, But How Will the People Know? Public Opinion as a Meager Influence in Shaping Contemporary Supreme Court Decision Making, 109 MICH. L. REV. 963 (2011). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol109/iss6/7 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUT HOW WILL THE PEOPLE KNOW? PUBLIC OPINION AS A MEAGER INFLUENCE IN SHAPING CONTEMPORARY SUPREME COURT DECISION MAKING Tom Goldstein* Amy Howe** THE WILL OF THE PEOPLE: How PUBLIC OPINION HAS INFLUENCED THE SUPREME COURT AND SHAPED THE MEANING OF THE CONSTITUTION. By Barry Friedman.New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2009. Pp. 614. $35. INTRODUCTION Chief Justice John Roberts famously described the ideal Supreme Court Justice as analogous to a baseball umpire, who simply "applies" the rules, rather than -

The Breadth of Congress' Authority to Access Information in Our Scheme

H H H H H H H H H H H 5. The Breadth of Congress’s Authority to Access Information in Our Scheme of Separated Powers Overview Congress’s broad investigatory powers are constrained both by the structural limitations imposed by our constitutional system of separated and balanced powers and by the individual rights guaranteed by the Bill of Rights. Thus, the president, subordinate officials, and individuals called as witnesses can assert various privileges, which enable them to resist or limit the scope of congressional inquiries. These privileges, however, are also limited. The Supreme Court has recognized the president’s constitutionally based privilege to protect the confidentiality of documents or other information that reflects presidential decision-making and deliberations. This presidential executive privilege, however, is qualified. Congress and other appropriate investigative entities may overcome the privilege by a sufficient showing of need and the inability to obtain the information elsewhere. Moreover, neither the Constitution nor the courts have provided a special exemption protecting the confidentiality of national security or foreign affairs information. But self-imposed congressional constraints on information access in these sensitive areas have raised serious institutional and practical concerns as to the current effectiveness of oversight of executive actions in these areas. With regard to individual rights, the Supreme Court has recognized that individuals subject to congressional inquiries are protected by the First, Fourth, and Fifth Amendments, though in many important respects those rights may be qualified by Congress’s constitutionally rooted investigatory authority. A. Executive Privilege Executive privilege is a doctrine that enables the president to withhold certain information from disclosure to the public or even Congress. -

R R R ---R R R R R R R R R R R R R

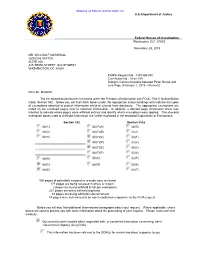

Obtained via FOIA by Judicial Watch, Inc. U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Washington, D.C. 20535 November 29, 2019 MR. WILLIAM F MARSHALL JUDICIAL WATCH SUITE 800 425 THIRD STREET, SOUTHWEST WASHINGTON, DC 20024 FOIPA Request No.: 1391365-000 Civil Action No.: 18-cv-154 Subject: Communications between Peter Strzok and Lisa Page (February 1, 2015 – Present) Dear Mr. Marshall: The enclosed documents were reviewed under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), Title 5, United States Code, Section 552. Below you will find check boxes under the appropriate statue headings with indicate the types of exemptions asserted to protect information which is exempt from disclosure. The appropriate exemptions are noted on the enclosed pages next to redacted information. In addition, a deleted page information sheet was inserted to indicate where pages were withheld entirely and identify which exemptions were applied. The checked exemption boxes used to withhold information are further explained in the enclosed Explanation of Exemptions. Section 552 Section 552a r (b)(1) r (b)(7)(A) r (d)(5) r (b)(2) r (b)(7)(B) r (j)(2) r (b)(3) P' (b)(7)(C) r (k)(1) -------- P' (b)(7)(D) r (k)(2) (b)(7)(E) (k)(3) -------- P' r -------- r (b)(7)(F) r (k)(4) (b)(4) r (b)(8) r (k)(5) (b)(5) r (b)(9) r (k)(6) (b)(6) r (k)(7) 500 pages of potentially responsive records were reviewed. 171 pages are being released in whole or in part. 2 pages are being withheld in full per exemptions. -

Finding Aid for the Post-Presidential Correspondence with Gerald R. Ford

Guide to the Post-Presidential Correspondence with Gerald R. Ford (1976-1993) Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum Contact Information Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum ATTN: Archives 18001 Yorba Linda Boulevard Yorba Linda, California 92886 Phone: (714) 983-9120 Fax: (714) 983-9111 E-mail: [email protected] Processed by: Susan Naulty and Richard Nixon Library and Birthplace archive staff Date Completed: December 2004 Table Of Contents Descriptive Summary 3 Administrative Information 4 Biography 5 Scope and Content Summary 7 Related Collections 7 Container List 8 2 Descriptive Summary Title: Post-Presidential Correspondence with Gerald R. Ford (1976-1993) Creator: Susan Naulty Extent: .25 document box (.06 linear ft.) Repository: Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum 18001 Yorba Linda Boulevard Yorba Linda, California 92886 Abstract: This collection contains correspondence relating to Gerald and Betty Ford and Richard Nixon from 1976 to 1993. Topics discussed include Presidential Museums and Libraries, a proposed Presidential pension increase, POW/MIA affairs, get well messages, and wedding announcements for the Ford children. 3 Administrative Information Access: Open Publication Rights: Copyright held by Richard Nixon Library and Birthplace Foundation. Preferred Citation: “Folder title”. Box #. Post-Presidential Correspondence with Gerald R. Ford (1976-1993). Richard Nixon Library & Birthplace Foundation, Yorba Linda, California. Acquisition Information: Gift of Richard Nixon Processing History: Originally processed and separated by Susan Naulty prior to September 2003, reviewed by Greg Cumming December 2004, preservation and finding aid by Kirstin Julian February 2005. 4 Biography Richard Nixon was born in Yorba Linda, California, on January 9, 1913. After graduating from Whittier College in 1934, he attended Duke University Law School. -

August 18, 2020 VIA FOIA ONLINE Kevin Krebs Assistant Director FOIA

August 18, 2020 VIA FOIA ONLINE Kevin Krebs Assistant Director FOIA/Privacy Unit Executive Office for United States Attorneys Department of Justice 175 N Street NE, Suite 5.400 Washington, DC 20530-0001 Via FOIA Online Re: Freedom of Information Act Request Dear FOIA Officer: Pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), 5 U.S.C. § 552, and the implementing regulations of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), 28 C.F.R. Part 16, American Oversight makes the following request for records. In May 2020, Attorney General William Barr tapped U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Texas John Bash to investigate “unmasking” practices—i.e., the intelligence community practice of revealing of the identity of an individual on a monitored communication—occurring before and after the 2016 presidential election.1 The move is part of a broader DOJ investigation into unmasking, which has raised concerns about political motivations within the DOJ.2 American Oversight seeks records with potential to shed light on Mr. Bash’s actions. Requested Records American Oversight requests that your agency produce the following records within twenty business days: 1 Quint Forgey, Barr Taps U.S. Attorney to Investigate ‘Unmasking’ as Part of Russian Probe Review, Politico (May 28, 2020, 9:25 AM), https://www.politico.com/news/2020/05/28/barr-russia-probe-attorney-286920. 2 See, e.g., Mark Hosenball, Former U.S. Officials Question DOJ’s Probe of ‘Unmasking’ of Trump Ally, Reuters (May 29, 2020, 6:08 AM), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa- intelligence-unmasking/former-u-s-officials-question-dojs-probe-of-unmasking-of-trump- ally-idUSKBN23519Q. -

Recommendations for the New Supreme Court Pro Bono Bar and Public Interest Practice Communities

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\86-1\NYU103.txt unknown Seq: 1 29-MAR-11 18:27 COUNTERBALANCING DISTORTED INCENTIVES IN SUPREME COURT PRO BONO PRACTICE: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE NEW SUPREME COURT PRO BONO BAR AND PUBLIC INTEREST PRACTICE COMMUNITIES NANCY MORAWETZ* The emergence of a new Supreme Court Pro Bono Bar, made up of specialty prac- tices and law school Supreme Court clinics, has altered the dynamic of litigation related to public interest issues. The new Bar often brings expertise in Supreme Court litigation to cases where there may otherwise be a dearth of resources to support high quality lawyering. But at the same time, this new Bar is subject to market pressures that have important consequences. This Article shows how mem- bers of this new Bar are engaged in a race for opportunities to handle Supreme Court cases on the merits. At the certiorari stage, this Bar can be expected to engage in truncated case analysis, avoid coordination with lawyers handling similar cases, and otherwise make decisions that are influenced by each firm’s interest in being in a position to handle cases on the merits before the Supreme Court. Moreover, throughout the litigation, this Bar may be influenced by the merits opportunity that provided the incentive to take the case in the first place. This Article explores the implications of this new dynamic in Supreme Court litigation for both pro bono practices and public interest practice communities. With respect to pro bono prac- tices, this Article proposes principles that firms could adopt, including those that relate to the selection of cases for free representation and those that relate to the nature of representation that the pro bono practices provide once the firm has taken on representation. -

The 2020 Election 2 Contents

Covering the Coverage The 2020 Election 2 Contents 4 Foreword 29 Us versus him Kyle Pope Betsy Morais and Alexandria Neason 5 Why did Matt Drudge turn on August 10, 2020 Donald Trump? Bob Norman 37 The campaign begins (again) January 29, 2020 Kyle Pope August 12, 2020 8 One America News was desperate for Trump’s approval. 39 When the pundits paused Here’s how it got it. Simon van Zuylen–Wood Andrew McCormick Summer 2020 May 27, 2020 47 Tuned out 13 The story has gotten away from Adam Piore us Summer 2020 Betsy Morais and Alexandria Neason 57 ‘This is a moment for June 3, 2020 imagination’ Mychal Denzel Smith, Josie Duffy 22 For Facebook, a boycott and a Rice, and Alex Vitale long, drawn-out reckoning Summer 2020 Emily Bell July 9, 2020 61 How to deal with friends who have become obsessed with 24 As election looms, a network conspiracy theories of mysterious ‘pink slime’ local Mathew Ingram news outlets nearly triples in size August 25, 2020 Priyanjana Bengani August 4, 2020 64 The only question in news is ‘Will it rate?’ Ariana Pekary September 2, 2020 3 66 Last night was the logical end 92 The Doociness of America point of debates in America Mark Oppenheimer Jon Allsop October 29, 2020 September 30, 2020 98 How careful local reporting 68 How the media has abetted the undermined Trump’s claims of Republican assault on mail-in voter fraud voting Ian W. Karbal Yochai Benkler November 3, 2020 October 2, 2020 101 Retire the election needles 75 Catching on to Q Gabriel Snyder Sam Thielman November 4, 2020 October 9, 2020 102 What the polls show, and the 78 We won’t know what will happen press missed, again on November 3 until November 3 Kyle Pope Kyle Paoletta November 4, 2020 October 15, 2020 104 How conservative media 80 E. -

Abraham Lincoln: Preserving the Union and the Constitution

ABRAHAM LINCOLN: PRESERVING THE UNION AND THE CONSTITUTION Louis Fisher* I. THE MEXICAN WAR ..................................................................505 A. Polk Charges Treason ...................................................507 B. The Spot Resolutions ....................................................508 C. Scope of Presidential Power .........................................510 II. DRED SCOTT DECISION ...........................................................512 III. THE CIVIL WAR .....................................................................513 A. The Inaugural Address.................................................515 B. Resupplying Fort Sumter .............................................518 C. War Begins ...................................................................520 D. Lincoln’s Message to Congress .....................................521 E. Constitutionality of Lincoln’s Actions .......................... 523 F. Suspending the Writ .....................................................524 G. Statutory Endorsement ................................................527 H. Lincoln’s Blockade .......................................................528 IV. COMPARING POLK AND LINCOLN ...........................................531 * Specialist in constitutional law, Law Library, Library of Congress. This paper was presented at the Albany Government Law Review’s symposium, “Lincoln’s Legacy: Enduring Lessons of Executive Power,” held on September 30 and October 1, 2009. My appreciation to David Gray Adler, Richard -

Presidential Succession and Impeachment: Historical Precedents, from Indiana and Beyond

REMARKS: PRESIDENTIAL SUCCESSION AND IMPEACHMENT: HISTORICAL PRECEDENTS, FROM INDIANA AND BEYOND JOHN D. FEERICK* I thank you for the opportunity to address you today on presidential succession and the impeachment provisions of the Constitution. Two heroes in my life as a lawyer are from this state. The first is former U.S. Senator Birch Bayh, who I first met in January 1964 when the American Bar Association assembled twelve lawyers and their guests to develop a position with respect to the subjects of presidential inability and vice-presidential vacancy. Bayh became the undisputed leader of the movement for change as a way of honoring a fallen President, John F. Kennedy, whose assassination two months before the ABA conference focused the nation on the gaps in the presidential succession system. Bayh also inspired me in the importance of a lawyer rendering public service. It is inspiring for me to give these remarks below the Speaker’s chair that he occupied. The second hero is Dean James White, a longtime professor at this law school, who served for thirty years as a consultant to the ABA in the areas of admission to the bar and legal education. He helped me transform from a practicing lawyer to an academic lawyer as a dean and professor at Fordham Law School. Today’s program on Indiana’s Vice Presidents of the United States is also part of my Indiana history. In 1966, I was asked to write a book for high school students, a first of its kind, on the vice presidents, which I proceeded to do with the help of my wife, Emalie.1 I learned in the process of four of the six Vice Presidents from Indiana: Schuyler Colfax, Thomas Hendricks, Charles Fairbanks, and Thomas Marshall. -

Thomas F. Eagleton: a Model of Integrity

Saint Louis University Law Journal Volume 52 Number 1 (Fall 2007) Article 18 2007 Thomas F. Eagleton: A Model of Integrity Louis Fisher Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Louis Fisher, Thomas F. Eagleton: A Model of Integrity, 52 St. Louis U. L.J. (2007). Available at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj/vol52/iss1/18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Saint Louis University Law Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarship Commons. For more information, please contact Susie Lee. SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW THOMAS F. EAGLETON: A MODEL OF INTEGRITY LOUIS FISHER* In 1975, I was invited to participate in an all-day conference held in Washington, D.C. to analyze Executive-Legislative conflicts. The objective was to survey the meaning of the pitched battles between Congress and the presidency during the Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon administrations. Throughout the morning and afternoon we were joined by senators and representatives. In an informed, thoughtful, and articulate manner they explained different issues, personalities, and procedures. Senior editors and writers from the media sat around the room listening intently. Occasionally I would watch their eyes and expressions to gauge their evaluations. That evening, at the Kennedy Center, we continued the conversation over cocktails and dinner. Again the editors and writers stood nearby to listen. After I finished a conversation with Senator Tom Eagleton, they quickly closed in around me and asked, visibly shaken: “Are other members of Congress this bright?” I assured them they were.