Edinburgh Research Archive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Temple Library Database 2017-05-17

Temple Sholom Library 6/9/2017 BOOK PUB CALL TITLE AUTHOR CATEGORY KEYWORDS FORMAT DATE NUMBER Children's Books : Literature : 10 Traditional Jewish Children's Stories Goldreich, Gloria Hardcover 1996 Children's stories, Hebrew, Legends, Jewish J 185.6 Go Classics by Age : General Feldman, 100+ Jewish Art Projects for Children Paperback 1996 Religion Biblical Studies Bible. O.T. Pentateuch Textbooks Margaret A. Language selfstudy & 1001 Yiddish Proverbs Kogos, Fred Paperback 1990 phrasebooks 101 Classic Jewish Jokes : Jewish Humor from Groucho Marx to Jerry Menchin, Robert Paperback 1997 Entertainment : Humor : General Jewish wit and humor 550.7 Seinfeld World War, 19141918 Peace, World War, 19141918 1918: War and Peace Dallas, Gregor Hardcover 2001 20th Century World History Armistices Kipfer, Barbara English language Style Handbooks, manuals,, etc, 21ST Century Style Manual Paperback 1993 English Composition Ann English language Usage Dictionaries 26 Big Things Small Hands Do Paratore, Coleen Paperback 1905 Tikkun olam J Pa 300 ways to ask the four questions : from Zulu to Abkhaz : an extraordinary survey of the world's languages through the prism of the Spiegel, Murray Hardcover 1905 Passover Mah nishtannah Translations 244.4 Sp Haggadah 5,600 Jokes for All Occasions Meiers, Mildred Hardcover 1905 Jewish Humor Jewish Humor 550.7 Me 50 Ways to be Jewish: Or, Simon & Garfunkel, Jesus loves you less Forman, David J. Hardcover 2001 Jewish living Jewish way of life, Judaism 20th century 246 Fo than you will know 700 sundays Crystal, Billy Hardcover 1905 Crystal, Billy Crystal, Billy, Comedians United States Biography B Cr FinkWhitman, 94 Maidens Paperback 1905 Fiction F Fi Rhonda A Backpack, A Bear, and Eight Crates of Vodka Golinkin, Lev Paperback 1905 Biographies & Memoirs B Go Jews Folklore, Folklore Europe, Eastern, Yiddish Folk A Big Quiet House Forest, Heather Hardcover 1996 Folklore J 185.6 Fo Tales Jews New York (State) New York Social, life and customs, Immigrants New York (State) New York , A Bintel brief. -

Library Collection 19-08-20 Changes-By-Title

Temple Sholom Library 8/20/2019 BOOK PUB CALL TITLE AUTHOR FORMAT CATEGORY KEYWORDS DATE NUMBER .The Lion Seeker Bonert, Kenneth Paperback Fiction 2013 F Bo Children's Books : Literature : 10 Traditional Jewish Children's Stories Goldreich, Gloria Hardcover Classics by Age : General Children's stories, Hebrew, Legends, Jewish 1996 J 185.6 Go 100+ Jewish Art Projects for Children Feldman, Margaret A. Paperback Religion Biblical Studies Bible. O.T. Pentateuch Textbooks 1984 1001 Yiddish Proverbs Kogos, Fred Paperback Language selfstudy & phrasebooks 101 Classic Jewish Jokes : Jewish Humor from Groucho Marx to Jerry Seinfeld Menchin, Robert Paperback Entertainment : Humor : General Jewish wit and humor 1998 550.7 101 Myths of the Bible Greenberg, Gary Hardcover Bible Commentaries 2000 .002 Gr 1918: War and Peace Dallas, Gregor Hardcover 20th Century World History World War, 19141918 Peace, World War, 19141918 Armistices English language Style Handbooks, manuals,, etc, English language Usage 21ST Century Style Manual Kipfer, Barbara Ann Paperback English Composition Dictionaries 26 Big Things Small Hands Do Paratore, Coleen Paperback Tikkun olam 2008 J Pa 3 Falafels in my Pita : a counting book of Israel Friedman, Maya Paperback Board books Counting, Board books, IsraelFiction BB Fr 300 ways to ask the four questions : from Zulu to Abkhaz : an extraordinary survey of the world's languages through the prism of the Haggadah Spiegel, Murray Hardcover Passover Mah nishtannah Translations 2015 244.4 Sp 40 Days and 40 Bytes: Making Computers Work for Your Congregation Spiegel, Aaron Paperback Christian Books & Bibles Church workData processing 2004 5,600 Jokes for All Occasions Meiers, Mildred Hardcover Jewish Humor Jewish Humor 1980 550.7 Me 50 Ways to be Jewish: Or, Simon & Garfunkel, Jesus loves you less than you will know Forman, David J. -

Narratology, Hermeneutics, and Midrash

Poetik, Exegese und Narrative Studien zur jüdischen Literatur und Kunst Poetics, Exegesis and Narrative Studies in Jewish Literature and Art Band 2 / Volume 2 Herausgegeben von / edited by Gerhard Langer, Carol Bakhos, Klaus Davidowicz, Constanza Cordoni Constanza Cordoni / Gerhard Langer (eds.) Narratology, Hermeneutics, and Midrash Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Narratives from the Late Antique Period through to Modern Times With one figure V&R unipress Vienna University Press Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. ISBN 978-3-8471-0308-0 ISBN 978-3-8470-0308-3 (E-Book) Veröffentlichungen der Vienna University Press erscheineN im Verlag V&R unipress GmbH. Gedruckt mit freundlicher Unterstützung des Rektorats der Universität Wien. © 2014, V&R unipress in Göttingen / www.vr-unipress.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk und seine Teile sind urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung in anderen als den gesetzlich zugelassenen Fällen bedarf der vorherigen schriftlichen Einwilligung des Verlages. Printed in Germany. Titelbild: „splatch yellow“ © Hazel Karr, Tochter der Malerin Lola Fuchs-Carr und des Journalisten und Schriftstellers Maurice Carr (Pseudonym von Maurice Kreitman); Enkelin der bekannten jiddischen Schriftstellerin Hinde-Esther Singer-Kreitman (Schwester von Israel Joshua Singer und Nobelpreisträger Isaac Bashevis Singer) und Abraham Mosche Fuchs. Druck und Bindung: CPI Buch Bücher.de GmbH, Birkach Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier. Contents Constanza Cordoni / Gerhard Langer Introduction .................................. 7 Irmtraud Fischer Reception of Biblical texts within the Bible: A starting point of midrash? . 15 Ilse Muellner Celebration and Narration. Metaleptic features in Ex 12:1 – 13,16 . -

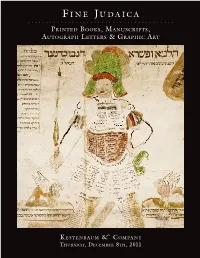

Fi N E Ju D a I

F i n e Ju d a i C a . pr i n t e d bo o K s , ma n u s C r i p t s , au t o g r a p h Le t t e r s & gr a p h i C ar t K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y th u r s d a y , de C e m b e r 8t h , 2011 K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 334 Catalogue of F i n e Ju d a i C a . PRINTED BOOKS , MANUSCRI P TS , AUTOGRA P H LETTERS & GRA P HIC ART Featuring: Books from Jews’ College Library, London ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 8th December, 2011 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 4th December - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 5th December - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 6th December - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday 7th December - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale. This Sale may be referred to as: “Omega” Sale Number Fifty-Three Illustrated Catalogues: $35 (US) * $42 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . -

Megillat RUTH: Hesed and Hutzpah a Literary Approach

Megillat RUTH: Hesed and Hutzpah A Literary Approach Study Guide by Noam Zion TICHON PROGRAM SHALOM HARTMAN INSTITUTE, JERUSALEM. Summer 2005, 5765 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION page 4 Structural/Scene Analysis of Megillah APPROACHES to Getting Started with the Narrative page 6 Theme #1 – Responses to Tragedy? Naomi, the Female Job? Theme #2 – A Woman’s Story in a Man’s World Theme #3 – A Romance of a migrant foreign-worker Widow and an aging landed Notable Theme #4 - Redemption of Land, of a Widow/er and of the Jewish people by the Ancestors of King David RUTH Chapter One – Abandoning Bethlehem for the Fields of Moav and Returning to Bethlehem page 9 Structural Analysis of Chapter Ruth 1: 1-7 EXPOSITION IN MOAB page 10 Literary Methods of Analysis: Exposition and Primary Associations: Ruth 1:1 Midrash Shem – Ruth 1:1-4 Divide up the chapter into subsections with titles, identify leitworter and plotline Elimelech – Midrashic Character Assassination Ruth 1: 8-18 – TRIALOGUE AT THE CROSSROADS page 18 From Fate to Character Literary Methods of Analysis: Character Development How does Naomi change in Chapter One? Dialogue of Naomi and her Daughters-in-law and Three-Four Literary Pattern The Mysterious Ruth the Moabite: What makes her Tick? Character Education: Friends or Best-Friends? 1 Megillat RUTH: Hesed and Hutzpah, A Literary Approach by Noam Zion Ruth as the Rabbis’ Star Convert Ruth 1: 19-22 – TRAGIC HOMECOMING page 34 The Female Job A Failed Homecoming Naomi as a Mourner: Reactions, Stages, Processes RUTH CHAPTER TWO - A Day in the Fields of Bethlehem page 42 Structural Analysis of Chapter page 42 Literary Methods of Analysis: page 44 Scenes Withholding and Releasing Information Type-Scene - Parallel Story in Same Genre – The Marriage Ordeal of Hesed – Gen. -

Temple Library Database 2017-05-17

Temple Swholom library 6/9/2017 BOOK PUB CALL TITLE AUTHOR CATEGORY KEYWORDS FORMAT DATE NUMBER Religion & Spirituality : Kabbalah, Spirituality, Jewlish Religeon, Mysticism, Jewish Endless Light: The Ancient Path of Kabbalah Aaron, David Paperback 1998 Judaism : Sacred Writings 159 Aa Mysticism : Kabbalah Jewish U: A Contemporary Guide for the Jewish College Student Aaron, Scott Paperback 2002 Education college guides, jewish 655 Aa Abells, Chana holocaust, children, jewish, world war ii, human rights, teaching, The Children We Remember Hardcover 1986 Reference works Byers the secret, law of attraction, young adult, greek, positive thinking Holocaust, Jewish (19391945) Pictorial works, Juvenile The children we remember : photographs from the Archives of Yad Abells, Chana Holocaust, Jewish (1939 Hardcover literature, Jewish children in the Holocaust Pictorial, works J 940.4 Vashem, Jerusalem, Israel Byers 1945) Pictorial works Juvenile literature, Holocaust, Jewish (19391945) Abraham, Michelle Judaism Customs and practices Fiction, Jews Israel My cousin Tamar lives in Israel Hardcover 1905 Israel Juvenile literature J Ab Shapiro Fiction Abrahams, Beth The Life of Gluckel of Hameln Hardcover 1905 Biography Gluckel of Hameln B Gu Zion TALES OF MENDELE THE BOOK PEDDLER: Fishke the Lame Jews Social life and customs Fiction, Love stories, Mock Abramovitsh, S.Y. Hardcover 1996 Jewish Studies F Ab and Benjamin the Third heroic literature Rosh Hashanah: A Family Service Abrams, Judith Z. Paperback 1990 Rosh Hashanah rosh hashanah J 239.1 Ab Children's Books : People Sabbath Liturgy Texts Juvenile, literature, Judaism & Places : Holidays & Shabbat a Family Service: A Family Service Abrams, Judith Z. Paperback 1991 Liturgy Texts Juvenile, literature, Sabbath, Judaism J 262.1 Ab Festivals : Around the Liturgy, Shabbat World 4for3 Books Store : Sukkot Prayerbooks and devotions English, Sukkot Sukkot: A Family Seder Abrams, Judith Z. -

Fine Judaica, to Be Held March 19Th, 2015

F i n e J u d a i C a . booKs, manusCripts, autograph Letters, CeremoniaL obJeCts, maps & graphiC art K e s t e n b au m & C om pa n y thursday, m a rCh 19th, 2015 K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 8 Catalogue of F i n e J u d a i C a . PRINTED BOOK S, MANUSCRIPTS, AUTOGRAPH LETTERS, CEREMONIAL OBJECTS, MAPS AND GRAPHIC A RT FEATURING: A COllECTION OF HOLY L AND M APS: THE PROPERT Y OF A GENTLEMAN, LONDON JUDAIC A RT FROM THE ESTATE OF THE LATE R AbbI & MRS. A BRAHAM K ARP A MERICAN-JUDAICA: EXCEPTIONAL OffERINGS ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 19th March, 2015 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 15th March - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday,16th March - 10:00 pm - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 17th March - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, 18th March - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Hebron” Sale Number Sixty-Four Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager: Jackie S. -

Convocation 2020 Changing Lives Congratulations! Class of 2020 Message from the Board of Governors

Convocation 2020 Changing Lives Congratulations! Class of 2020 Message from the Board of Governors Graduation is a time to be proud of all that our learners have achieved. On behalf of the Algonquin College Board of Governors, I am pleased to share in the pride that you, our learners, your families and supporters experience today. Your hard work and dedication towards your success is celebrated today. As you transition to the next phase of your lifelong learning journey, I hope that the experiences that you have had at Algonquin College will support you and enable you to continue to “transform your hopes and dreams into lifelong success”. Our world is undergoing the most rapid rate of change that it has ever experienced. Each of you will face many opportunities and challenges for advancement. Algonquin College is constantly engaged in preparing our learners for this world of change. Should you require further upgrading of your education, don’t forget to consider returning to our campuses or to take advantage of our extensive on-line learning resources. As you become an alumnus of Algonquin College, I encourage you to stay in touch. The contacts that you have made with Faculty and Staff can remain as an ongoing resource as you leave this institution of learning. Your friends and colleagues at Algonquin can remain as such for many years to come. Share your experiences and success with them. Our Faculty, Staff, our Executive Team and the Board of Governors are pleased that you chose Algonquin in your search for education. As graduates you have an opportunity to become ambassadors of Algonquin College. -

Strength in Torah & Emuna

RELIEF has the haskama & guidance ofleading Rabbonim NEW YORK lder adults have specific physical, emotional, and social needs 5904 13m Avenue Brooklyn, NY 11219 that require specialized care. Through our extensive research, 718.431.9501 RELIEF has developed a comprehensive database of geriatric mental PAX O 718.431.9504 health professionals specially trained to treat the elderly. If you or someone NI:W JERSEY you know is suffering from depression, anxiety, dementia, or any other mental 110 Hillside Boulevard health disorder, RELIEF can guide you to the most qualified provider. Lakewood, NJ 08701 732.905.1605 Call RELIEF to get the help and support you need. CAKADA 3101 Bathurst Street Toronto, ON M6A 2A6 Our services are free of 416.789.1600 charge and completely E L I E F confidential. IS RAEL Nadvorna 23/3 Beitar Illit, Israel 90500 n Ell EF is a non~profit organization which provides medical referrals, support and other vital services 02.580.8008 ~ to persons suffering from a variety of mental disorders including Anxiety, Bipolar Disorder, Eating EMAIL: [email protected] Disorders, Depression, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, and many others. These services are geared to v1s1r: www.reliefhelp.org the frum community with a special sensitivity to their unique needs and challenges. THE JEWISH OBSERVER ' 4 NOTED JN SORROW: RABB! NOACH WEINBERG, 7 ~1' THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN) OOU-6615 IS PUBLISHED MONTHLY, EXCEPT JULY & AUGUST LESSONS FROM THE GAZA WAR AND A COMBINED ISSUE FOR JANVARYlfEBRUARY, BY THE 5 AN AGE OF MIRACLES, AN EDITORIAL INTRODUCTION, AGUDATH IS RAEL OF AMERICA. 42 BROADWAY, NEW YORK, NY 10004. -

Jerzy Strzelczyk Zapomniane Narody Europy

Strzelczyk Jerzy Zapomniane narody Europy W s t ę p Uczony biskup krakowski i wybitny humanista Piotr Tomicki (1464-1535) w trakcie licznych podróży nie ominął i Niemiec, studia swoje zresztą rozpoczął w Lipsku. Nie wiadomo dokładnie, co i gdzie skłoniło go do refleksji na temat dawnej ludności słowiańskiej w Niemczech, mieszkającej niegdyś - jak mniemał zresztą nie bez znacznej przesady - aż do Renu. Melancholijnej refleksji dał wyraz we własnoręcznej notatce na marginesie pewnej książki, która trafiła do jego biblioteki: „Oto, jak królestwa przechodzą od jednego narodu do drugiego, zmieniając swoje nazwy”. W refleksji tej, na co trafnie zwrócił uwagę Stanisław Kot, nie ma ani śladu jakiejś wrogości wobec Niemców, którzy odebrali Słowianom ich dziedziny, ani tym bardziej jakiejkolwiek sugestii, by „naprawić błąd historii” i przywrócić dawny stan rzeczy. Widoczna jest jedynie filozoficzna zaduma nad zmiennością fortuny, skazującej jedne narody na przemijanie i zapomnienie, inne wynoszącej na scenę dziejową. Można w tym dostrzec echo postępującej dojrzałości elit intelektualnych polskiego odrodzenia, kiedy to dość szybko społeczeństwo polskie zdawało się nadrabiać dystans cywilizacyjny wobec przodujących rejonów Europy. Niestety, później dystans ten zaczął ponownie narastać, przyjmując niepokojące rozmiary, czego skutki dotkliwie dają się nam we znaki do dzisiaj. W jednym z rozdziałów niniejszej książki przyjrzymy się ludowi, którego losy dały być może Tomickiemu okazję do przytoczonej refleksji. Zamysł książki jest nieskomplikowany. Zapragnąłem mianowicie przedstawić Czytelnikom kilka mniej znanych kart z dziejów naszego kontynentu. W ośmiu szkicach przedstawiłem osiem ludów, które niegdyś odgrywały określoną, mniej lub bardziej ważną, ale zawsze godną uwagi rolę w dziejach Europy, później zaś zeszły ze sceny dziejowej, pozostawiając dość nikłe na ogół i nie zawsze łatwo dostrzegalne ślady swojego istnienia. -

Megillat RUTH: Hesed and Hutzpah Table of Contents

Megillat RUTH: Hesed and Hutzpah A Literary Approach Study Guide by Noam Zion TICHON PROGRAM SHALOM HARTMAN INSTITUTE, JERUSALEM. Summer 2005, 5765 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION page 4 Structural/Scene Analysis of Megillah APPROACHES to Getting Started with the Narrative page 6 Theme #1 – Responses to Tragedy? Naomi, the Female Job? Theme #2 – A Woman’s Story in a Man’s World Theme #3 – A Romance of a migrant foreign-worker Widow and an aging landed Notable Theme #4 – Redemption of Land, of a Widow/er and of the Jewish people by the Ancestors of King David RUTH Chapter One – Abandoning Bethlehem for the Fields of Moav and Returning to Bethlehem page 9 Structural Analysis of Chapter Ruth 1: 1-7 EXPOSITION IN MOAB page 10 Literary Methods of Analysis: Exposition and Primary Associations : Ruth 1:1 Midrash Shem – Ruth 1:1-4 Divide up the chapter into subsections with titles, identify leitworter and plotline Elimelech – Midrashic Character Assassination Ruth 1: 8-18 – TRIALOGUE AT THE CROSSROADS page 18 From Fate to Character Literary Methods of Analysis: Character Development How does Naomi change in Chapter One? Dialogue of Naomi and her Daughters-in- law and Three-Four Literary Pattern The Mysterious Ruth the Moabite: What makes her Tick? 1 Character Education: Friends or Best-Friends? Ruth as the Rabbis’ Star Convert Ruth 1: 19-22 – TRAGIC HOMECOMING page 34 The Female Job A Failed Homecoming Naomi as a Mourner: Reactions, Stages, Processes RUTH CHAPTER TWO - A Day in the Fields of Bethlehem Structural Analysis of Chapter page 42 Literary Methods of Analysis: page 44 Scenes Withholding and Releasing Information Type-Scene - Parallel Story in Same genre – The Marriage Ordeal of Hesed – Gen. -

A Concise Chronology of Biblical History

10.13146/OR-ZSE.2009.003 AAA CCCOONNCCIISSEEONCISE CCCHRONOLOGHRONOLOGYYYY OOFFOF BBBIBLICAL HHHIISSTTOORRYYISTORY PART I FFFROM THE CCCREATION OF THE WWWORLD UNTIL YYYEETTZZIIAASSETZIAS MMMITZRAYIM PhD-DISSERTATION Balázs Fényes OR-ZSE Budapest 2008 Consulents: Dr. György Haraszti & dr. János Oláh 10.13146/OR-ZSE.2009.003 2 „Remember the days of old, consider the years of many generations; ask your father, and he will show you; your elders, and they will tell you.” (Devorim 32:7) 10.13146/OR-ZSE.2009.003 3 Preface ,”a, „Be glad, oh Heavens and rejoice, oh Earthייישמחו הההשמים ווותגל הההארץ blessed be Hashem, our G-d, King of the Universe, Who kept me alive, sustained me, and brought me to this moment when He who graciously endows man with wisdom enabled me to end the first part of this work. The following paper was originally intended to serve as working material for a series of lectures which I held years ago in a high-school. Essentially, it 1 followed the „Sefer Seder haDoros” of Jechiel HALPERIN. With the time, I collected more and more material, from many other sources, primarily the aggadic corpus of the Two Talmuds, the different Midrashim and the commentaries. What actually the reader will find on the following pages, after an introduction about time-reckoning, the different calendar systems and World- Eras, is a chronological overview of Biblical history from Creation until the Exode. Although the Torah is not a book of history, nevertheless we can find there many „historical” informations also. And the background of these short informations has been conserved by the aggadic tradition.