Men and Open Defecation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Go Before You Go: How Public Toilets Impact Public Transit Usage

PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal Volume 8 Issue 1 The Impact of Innovation: New Frontiers Article 5 in Undergraduate Research 2014 Go Before You Go: How Public Toilets Impact Public Transit Usage Kate M. Washington Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mcnair Part of the Social Welfare Commons, Transportation Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Washington, Kate M. (2014) "Go Before You Go: How Public Toilets Impact Public Transit Usage," PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 5. https://doi.org/10.15760/mcnair.2014.46 This open access Article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). All documents in PDXScholar should meet accessibility standards. If we can make this document more accessible to you, contact our team. Portland State University McNair Research Journal 2014 Go Before You Go: How Public Toilets Impact Public Transit Usage by Kate M Washington Faculty Mentor: Dr. James G. Strathman Washington, Kate M. (2014) “Go Before You Go: How Public Toilets Impact Public Transit Usage” Portland State University McNair Scholars Online Journal: Vol. 8 Portland State University McNair Research Journal 2014 Abstract The emphasis on sustainable solutions in Portland, Oregon includes developing multi-modal transportation methods. Using public transit means giving up a certain amount of control over one’s schedule and taking on a great deal of uncertainty when it comes to personal hygiene. -

Technology Review of Urine-Diverting Dry Toilets (Uddts) Overview of Design, Operation, Management and Costs

Technology Review of Urine-diverting dry toilets (UDDTs) Overview of design, operation, management and costs As a federally owned enterprise, we support the German Government in achieving its objectives in the field of international cooperation for sustainable development. Published by: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH Registered offices Bonn and Eschborn, Germany T +49 228 44 60-0 (Bonn) T +49 61 96 79-0 (Eschborn) Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 40 53113 Bonn, Germany T +49 228 44 60-0 F +49 228 44 60-17 66 Dag-Hammarskjöld-Weg 1-5 65760 Eschborn, Germany T +49 61 96 79-0 F +49 61 96 79-11 15 E [email protected] I www.giz.de Name of sector project: SV Nachhaltige Sanitärversorgung / Sustainable Sanitation Program Authors: Christian Rieck (GIZ), Dr. Elisabeth von Münch (Ostella), Dr. Heike Hoffmann (AKUT Peru) Editor: Christian Rieck (GIZ) Acknowledgements: We thank all reviewers who have provided substantial inputs namely Chris Buckley, Paul Calvert, Chris Canaday, Linus Dagerskog, Madeleine Fogde, Robert Gensch, Florian Klingel, Elke Müllegger, Charles Niwagaba, Lukas Ulrich, Claudia Wendland and Martina Winker, Trevor Surridge and Anthony Guadagni. We also received useful feedback from David Crosweller, Antoine Delepière, Abdoulaye Fall, Teddy Gounden, Richard Holden, Kamara Innocent, Peter Morgan, Andrea Pain, James Raude, Elmer Sayre, Dorothee Spuhler, Kim Andersson and Moses Wakala. The SuSanA discussion forum was also a source of inspiration: http://forum.susana.org/forum/categories/34-urine-diversion-systems- -

Japan on Holiday – Experience Top Hygiene the Entire World Is Looking to Japan in Time for the 2021 Olympic Games

MEDIA INFORMATION Japan on holiday – experience top hygiene The entire world is looking to Japan in time for the 2021 Olympic Games. Anyone travelling to Japan will experience a bathing culture with unparalleled hygiene in most places. At the heart of this is a development still unfamiliar to many Europeans – the shower toilet or WASHLET™, as most in Japan call it. The 2021 Olympic Games are around the corner! Due to the current restrictions, Press office UK: only a few spectators will be lucky enough to travel to Tokyo for this historic event. INDUSTRY PUBLICITY From the moment they arrive, however, they will have the chance to experience Phone: the outstanding hygiene Japan is known for – especially in restrooms. “Toilets are +44 (0) 20 8968 8010 a symbol of Japan’s world-renowned culture of hospitality,” explained the Nippon hq@industrypublicity. Foundation on their website https://tokyotoilet.jp/en/. The foundation also initiates co.uk and supports other social projects. They asked TOTO to supply the equipment for public toilets in Tokyo designed by internationally renowned architects. Travellers Press office Europe: will also find hygienic shower toilets and other sanitary ware from TOTO on the Anja Giersiepen planes flown by Japanese airlines and upon arrival at Tokyo’s Narita International anja.giersiepen@ Airport. toto.com Travellers flying with a Japanese airline will have the chance to use WASHLET™ TOTO on the Internet: on the plane. Once they arrive at Terminal 2 in Tokyo’s Narita International Airport, gb.toto.com they will enjoy the distinctive hygiene culture in Japan that is closely linked to TOTO – the country’s undisputed market leader of sanitary products, responsible for selling the most shower toilets around the world. -

ADA Design Guide Washrooms & Showers

ADA Design Guide Washrooms & Showers Accessories Faucets Showers Toilets Lavatories Interactive version available at bradleycorp.com/ADAguide.pdf Accessible Stall Design There are many dimensions to consider when designing an accessible bathroom stall. Distances should allow for common usage by people with a limited range of motion. A Dimension guidelines when dispensers protrude from the wall in toilet rooms and 36" max A toilet compartments. 915 mm Anything that a person might need to reach 24" min should be a maximum of 48" (1220 mm) off of 610 mm the finished floor. Toilet tissue needs to be easily within arm’s 12" min reach. The outlet of a tissue dispenser must 305 mm be between 24" (610 mm) minimum and 42" (1070 mm) maximum from the back wall, and per the ANSI standard, at least 24" min 48" max 18" above the finished floor. The ADA guide 610 mm 1220 mm defines “easily with arm’s reach” as being within 7-9" (180–230 mm) from the front of 42" max the bowl and at least 15" (380 mm) above 1070 mm the finished floor (48" (1220 mm) maximum). Door latches or other operable parts cannot 7"–9" 18" min 180–230 mm require tight grasping, pinching, or twisting of 455 mm the wrist. They must be operable with one hand, using less than five pounds of pressure. CL Dimensions for grab bars. B B 39"–41" Grab Bars need to be mounted lower for 990–1040 mm better leverage (33-36" (840–915 mm) high). 54" min 1370 mm 18" min Horizontal side wall grab bars need to be 12" max 455 mm 42" (1065 mm) minimum length. -

Owner's Manual

® OWNER’S MANUAL Model: Neo 180 Thank you for choosing Luxe Bidet ®. This manual contains important information regarding your unit. Before operating the unit, please read this manual thoroughly, and retain it for future reference. ® TABLE OF CONTENTS PRODUCT INFORMATION Product Features page 1 Why Luxe Bidet? page 2 Specifications page 3 Product Dimensions page 3 Parts List page 4 PRODUCT INSTALLATION Before Installation page 5 Installation page 6 PRODUCT OPERATION Troubleshooting page 9 FAQs page 12 WARRANTY page 14 CONTACT page 15 PRODUCT INFORMATION PRODUCT FEATURES Dual Nozzle Design The Luxe Bidet Neo 180 is equipped with dual nozzles for rear and frontal wash. The frontal or feminine wash is gentler than the rear spray. It can be useful for monthly cycles and is highly recommended by new or expecting mothers. The dual nozzles are used as different modes, but can be used by both sexes. Nozzle Guard Gate The bidet features a convenient, hygienic nozzle guard gate for added protection and easy maintenance. The hygienic nozzle guard gate ensures that the bidet is always ready for clean operation and can open for easy access to the nozzles. Retractable Nozzle Always Stays Clean When not in use, the nozzles retract for hygienic storage allowing for double protection behind the nozzle guard gate. Convenient Nozzle Cleaning Feature While the bidet is designed to keep the retractable nozzles clean, this model also features an innovative self-cleaning sanitary nozzle that streams fresh water directly over the nozzles for rinsing before or after use. Activate and Adjust Water Pressure Easily The unobtrusive control panel features a chrome-plated lever that allows the user to activate and adjust water pressure. -

Introducing the Next Generation of Swash Advanced Bidet Toilet Seats…… It’S Going to Bring Potty Talk to a Whole New Level

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Brondell Inc. (888) 542-3355 [email protected] Introducing the Next Generation of Swash Advanced Bidet Toilet Seats…… It’s going to bring potty talk to a whole new level San Francisco, CA – December 7, 2010 Imagine this: after a long day, you finally make it home and into the comfort of your own bathroom. You sit down on the perfectly heated seat and a wave of relaxation comes over you. You press the easy to use remote control to release a stream of aerated, warm water that’s aimed just right. No, you’re not dreaming, you’re Swashing. Introducing the Brondell next generation Swash 1000 advanced bidet toilet seat; it’s the number one seat for your number two business. Brondell released the first Swash to the US market in 2004 and is now looking (and smelling) better than ever as one of the leading providers of advanced bidet toilet seats with the launch of the new Swash 1000. One of the most technologically advanced bidet seats in the industry, the Swash 1000 offers an unlimited warm water posterior and feminine wash at the push of a button. The wash temperature, spray strength, spray width and nozzle positions can all be easily controlled by the user for the perfect cleansing, every time, no matter how dirty the job. The heated seat, adjustable warm air dryer, automatic deodorizer, and dual stainless steel nozzles with sterilization make the Swash 1000 the true Cadillac of toilet seats. Simply put, when comparing features, quality, and price ($599 retail) - the Brondell Swash 1000 blows the competition out of the water. -

Urine Diversion Dry Toilet: a Narrative Review on Gaps and Problems and Its Transformation

European Journal of Behavioral Sciences ISSN 2538-807X Urine Diversion Dry Toilet: A Narrative Review on Gaps and Problems and its Transformation 1* 2 3 Govinda Prasad Devkota , Manoj K. Pandey , Shyam Krishna Maharjan 1 PhD Research Scholar, Graduate School of Education, Tribhuvan University, Nepal 2 Faculty of Environmental Sciences and Natural Resource Management, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Norway 3 Central Department of Education, Tribhuvan University, Nepal ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: This review paper highlights the gaps and problems on source Eco-San Toilet separation of human excreta; implementing and adopting human Nutrients urine as nutrients for agriculture. The objective of the paper is to School Education appraise the historical context behind the promotion of Urine Transformation Diversion Dry Toilet/Eco-san toilet and its relevance in rural Nepalese context. Moreover, it highlights the experiences regarding agricultural perspectives and livelihood by applying human urine as a fertilizer. Furthermore, it helps to understand and analyze the major issues, gaps and problems in acceptance and use of human excreta in Nepalese context for scaling up of its application and its transformation through school education system. Database search based on ‘Free text term’ or key word search was the strategy used to map of all relevant articles from multiple databases; Medline (1987-2018), MeSH (2005-2018), CINAHL (1998-2018) and OvidMedline (1992-2019). For each the outputs were downloaded into RefWorks databases. Specifically, this paper focuses on urine diversion to demonstrate its potential to elegantly separate and collect as nutrients and desire to control pathogens and micro- pollutants help in sanitation. It is recommended that an urgent need to participate community people and school children to disseminate users’ perceptions, attitudes and behaviour concerning the urine diversion toilets. -

Toilet & Urinal Cleaner

71 ToileT & Urinal Cleaner Fast-acting toilet bowl and urinal cleaner formulated for daily use on your most challenging restroom issues Product descriPtion Sustainable Earth by Staples® Toilet and Urinal Cleaner 71 (SEB71) has several advantages over conventional cleaners. It is a safe, versatile, eco-preferable* product that does not sacrifice cleaning performance. It is a concentrated toilet bowl and urinal cleaner that dilutes at one ounce per fixture (toilet or urinal) in most cleaning situations. It is specially formulated to clean, remove stains, eliminate and neutralize urinal odors and brighten toilet bowls and urinals without the use of hydrochloric, phosphoric or oxalic acid. SEB71 can be safely used daily on porcelain, porcelain enamel or stainless steel without etching or damaging them. Features Performance data • Contains no hydrochloric, phosphoric or hydrofluoric acids dilution ratio: one ounce per toilet or urinal fixture • Thickened to cling to vertical toilet and urinal surfaces Soap scum removal from shower walls Outstanding • Removes calcium, magnesium and iron residues Removal of soil deposits on toilets and urinals Outstanding • Instantly removes toilet and urinal soils from inside and outside Mineral deposit ring removal from toilets/urinals Very good of toilet and urinal bowls Brightening of metal fixtures in restroom Outstanding • Effective on both oil- and water-based soils Cleaning and polishing porcelain surfaces Outstanding • Will not etch toilet and urinal surfaces Cleaning and polishing porcelain enamel Outstanding -

Frequently Asked Questions About Low Flow Toilets

Water Conservation Devices » Selecting a Toilet? » Be Sure The Toilet Will Work In Your Building » Purchasing an ultra-low-flush toilet » Choosing a Licensed Plumber/Contractor » What should I know about maintaining 1.6 gpf toilets? » Disclaimer of Liability Selecting a Toilet Not all ultra low-flush toilets are the same. The ultra low-flush toilet you would install in your multiplex, commercial or industrial bathroom will probably be different from the toilet you install in your home. You want to buy a new toilet and you want to make sure it works properly. Toilets have two basic operational elements: (1) the intake of water used for flushing and (2) the discharge of wastewater. However, there are different types of toilets based on the way they perform these operations. You need to identify which type(s) of toilets are currently in your building and which is the most appropriate type to replace them with before you make a purchase. Gravity-Fed Tank Toilets: If you see freestanding water when peering down into the tank, your toilet is gravity-fed. Gravity toilets, which have a bowl and a tank, are the most common type of toilet found in residential settings but are in some commercial/business settings. They rely on the weight of the water and head pressure (height of the water in the tank) to promote the flush. They depend on the volume of water in the tank to flush wastes and usually require water pressure of no more than 10 - 15 pounds per square inch (psi) to operate properly. -

WAHO Commemorates World Toilet Day: “Sustainable Sanitation and Climate Change"

WAHO Commemorates World Toilet Day: “Sustainable Sanitation and Climate Change". Bobo Dioulasso, 19 November 2020, today, the West African Health Organization (WAHO), committed alongside Member States and Development Partners to promote the health of the people of West Africa, celebrates World Toilet Day under the theme "Sustainable Sanitation and Climate Change". What is it about? The aim of the day is to raise awareness and trigger global action to address the precarious sanitation crisis in which 4.2 billion of the world's population live without safely managed access to sanitation.1 It is also anticipated that deliberate changes in practice, policies and programs will contribute, in no small measure toward achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 6). The resolution which declared 19 November as World Toilet Day (WTD), was adopted on 24 July 2013 by the United Nations, therefore making it a global event.2 This was years after the first celebration of a toilet day took place in 2001. The resolution urges UN Member States and relevant stakeholders to encourage behavioral change and the implementation of policies to increase access to sanitation among the poor, along with a call to end the practice of open-air defecation, which it deemed “extremely harmful” to public health and emphasizes the need for the restoration of human dignity, health and well-being for economic development. What are the implications for global health? It is reported that over 673 million people currently practice open defecation, one in three people lack access to safe drinking water and two out of five people with no basic handwashing facilities such as soap and water. -

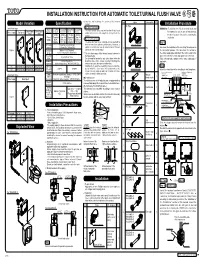

Installation Instruction for Automatic Toilet/Urinal Flush Valve

INSTALLATION INSTRUCTION FOR AUTOMATIC TOILET/URINAL FLUSH VALVE 4. Use care not to damage the surface of the infrared Item Figure Description Q’ty Model Variation Specification sensor. Installation Procedure AC Type 5. For Toilet Flush Valve Toilet Flush Valve WARNING: To minimize the risk of electrical shock and Model TET2ANS TET2DNS TEU2ANS TEU2DNS The toilet sensor valve may not function if toilet seat Water Supply Top Spud Back Spud Back Spud Number -32,33,31 -32,33,31 -11,21 -11,21 fire hazard, be sure to turn off and lock out Floor Wall and/or lid cover are left upright as it may block the 10V DC Alkaline 10V DC Alkaline sensor. breaker for power line before starting the Power Supplied Type AA Supplied Type AA installation. supply by AC Batteries by AC Batteries 6. For Urinal Flush Valve Adapter 1.5V x 4pcs. Adapter 1.5V x 4pcs. The automatic flush valve is designed to be used with a Step 1 Dimensions 12-5/8"(H) x 14-3/16"(W) washout urinal for optimum performance. However, a Only for toilet flush valve (cover) (320mm(H) x 360mm(W)) siphon jet urinal may also be substitutional. Blowout C Box 1 Determine the installation of the box fixing frame based on Figure Detection Within 31-1/2"(800mm) urinals are not recommended. DC Type the toilet/urinal position. Then determine the location of range from the front of the flush valve 7. The detection range of the infrared sensor is shown in the water supply pipe and attach the control stop to the Detection the figure below. -

Incomplete Bladder Emptying and Tips to Help

A guide for patients about incomplete bladder emptying and tips to help What is incomplete bladder emptying? When the bladder doesn't empty properly this may cause numerous problems. One of the problems is known as overflow incontinence. This is when the bladder doesn’t empty and urine leaks out. You may not get the message to go to the toilet either. The bladder never empties completely so some residue is normal. You may find it difficult to start to pass water and that even when you have started; the flow is weak and slow. You might find that you dribble after you have finished passing water. Perhaps you dribble urine all the time, even without noticing. What causes incomplete bladder emptying? Incomplete bladder emptying occurs when the muscles of the bladder are not able to squeeze properly to empty the bladder. This can happen in cases where there may have been nerve or muscle damage, perhaps caused by injury, surgery, or disease such as Parkinson's disease, Multiple Sclerosis and Spina Bifida. Medication can also cause problems with bladder emptying. In some cases, it can be due to an obstruction which is making it more difficult for you to empty your bladder. This obstruction can be caused by an enlarged prostate in men, a kidney stone blocking the urethra, constipation, or stricture of the urethra in either men or women, which makes it difficult for urine to flow out of the bladder outlet. If you are not able to empty completely, your bladder and its muscles may become floppy over time.